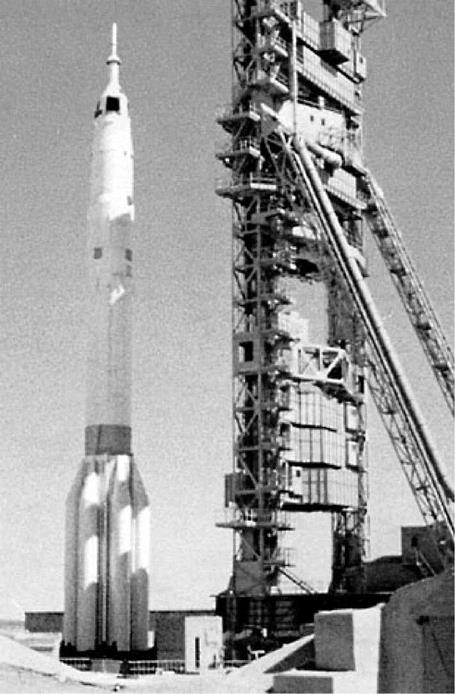

THE ROCKET FOR THE LANDING: THE N-l

In contrast to Proton, the N-1’s design history has been chronicled in some detail. The N-1 programme began on 14th September 1956, when the first sketches appeared in the archive of OKB-1. Korolev gave it the relatively bland name of N-1, ‘N’ standing for Nositel or carrier, with the industry code of 11A51. The concept was brought to the Council of Chief Designers on 15th July 1957, but it did notwin endorsement. The N-1 at this stage was a large rocket able to put 50 tonnes into orbit.

This was in dramatic contrast with the United States, where the Saturn V was constructed around a single mission: a manned moon landing. The N rocket, by contrast, was a universal rocket with broad applications. Korolev kept these purposes deliberately vague and, in order to keep military support for the project, hinting at how the N-1 could launch military reconnaissance satellites. The sending of large payloads to 24 hr orbit was also envisaged.

The N-1 languished for several years. Unlike the R-7, then in development, it did not have any precise military application and as a result the military would not back it. The situation changed on 23rd June 1960 when the N-1 was approved by Resolution #715-296 of the government and party called On the creation of powerful carrier rockets, satellites, space ships and the mastery of cosmic space 1960-7. Encouraged by the success of early Soviet space exploration, aware of reports of the developments by the United States of the Saturn launch vehicle, the Soviet government issued a party and government decree which authorized the development of large rocket systems, such as the N-1, able to lift 50 tonnes. The decree also authorized the development of liquid hydrogen, ion, plasma and atomic rockets. The 1960 resolution included approval for an N-2 rocket (industry code 11A52), able to lift 75 tonnes, but it was dependent on the development of these liquid hydrogen, ion, plasma and nuclear engines, suggesting it was a more distant prospect. The 1960 resolution also proposed circumlunar and circumplanetary missions. The implicit objective of the N-1 was to make possible a manned mission to fly to and return from Mars.

Such a mission was mapped out by a group of engineers led by Gleb Yuri Maksimov in Department # 9, overseen by Mikhail Tikhonravov. This would not be a landing, but a year-long circumplanetary mission. Maksimov’s 1959-61 studies postulated a heavy interplanetary ship, or TMK, like a daisy stem (nuclear power plant at one end, crew quarters at the opposite), which would fly past Mars and return within a year. In 1967-8, three volunteers – G. Manovtsev, Y. Ulybyshev and A. Bozhko – spent a year in a TMK-type cabin testing a closed-loop life support system. A related project, also developed in Department #9 but this time by designer Konstantin Feoktistov, envisaged a landing on Mars using two TMKs. The N-1 design, although it proved problematical for a man-on-the-moon project, was actually perfect for the assembly of a Mars expedition in Earth orbit.

Siddiqi points out that the N-1 Mars project and the development of related technologies took up a considerable amount of time, resources and energy at OKB-1 over 1959-63 [3]. Were it not for the Apollo programme, the Russians might well have by-passed the moon and sent cosmonauts to Mars by the end of the decade. Ambitious though the Apollo project was, Korolev had all along planned to go much farther.

The slogan of the GIRD group, written by Friedrich Tsander, never referred to the moon at all. Instead, its motto was ‘Onward to Mars!’

The fact that the original payload was 50 tonnes, far too little for a manned moon mission, demonstrates how little a part a moon landing played in Korolev’s plans at this time. Indeed, unaware of its origins, several people later questioned the suitability of the N-1 for the moon mission. Sergei Khrushchev said it was neither fish nor fowl, too large for a space station module, too small for a lunar expedition [4]. The head of the cosmonaut squad, General Kamanin, took the view in the mid-1960s that the design, going back to 1957, was already dated. The rival and ambitious Vladimir Chelomei felt he could do better with a more modern design.

Despite approval in 1960, the N-1 made very slow progress, and early the following year Korolev was already complaining that he was not getting the resources he needed. At one stage, in 1962, the government halted progress, limiting the N-1 project only to plans. An early problem, one that was to engulf the project, was the choice of engine. Korolev needed a much more powerful engine for such a large rocket. Korolev proposed kerosene-based engines for the lower stages and hydrogen – powered engines for the upper ones. He turned, as might be expected, to Valentin Glushko of OKB-456, asking him to design and build such engines. Valentin Glushko proposed a series of engines for the different stages of the N-1: the RD-114, RD-115, RD-200, RD-221, RD-222, RD-223. None of these was acceptable to Korolev, for all were nitric-based, anathema to him [5].

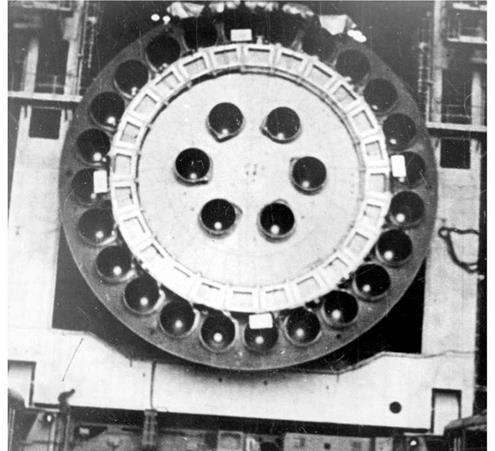

The ever-resourceful Korolev then turned to Kyubyshev plane-maker Nikolai Kuznetsov, asking him to make the engines using the traditional fuels of kerosene and liquid oxygen. Although Kuznetsov had no experience of rocket engines, he and his OKB-276 design bureau were prepared to give it a try. However, he knew he had no ability to develop high-powered engines, so a large number of modest-power kerosene-fuelled engines would have to do. In fact, despite his inexperience, the engines came out exceptionally powerful and lightweight, achieving the best thrust-to – weight ratios of the period. The engines were called NK, NK standing for Nikolai Kuznetsov. The first stage used NK-33s, the second NK-43s. There was little difference between them except that NK-43 was designed for higher altitudes and had a larger nozzle [6]. Roll was controlled by a series of roll engines. For example, on the first stage, there were four roll engines of 7 tonne thrust each, assisted by four aerodynamic stabilizers.

First-stage separation would take place at 118 sec, at 41.7-km altitude, by which time the rocket would be travelling at 2,317 m/sec. The second stage would burn for over a further two minutes, reaching 110.6 km, with speed now at 4,970 m/sec. The third stage would then burn until 583 sec, by which time the stack had reached orbital altitude of 300 km and a velocity of 7,790 m/sec. Translunar orbit injection would be done by block G. This would use a single NK-31 engine, burning for 480 sec, to fire the stack moonward. Block D would then be used three times: [3]

|

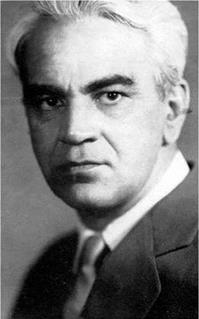

Mstislav Keldysh |

The N-1 was originally designed to have hydrogen-powered upper stages. Research on hydrogen engines dated to 1959 in Arkhip Lyulka’s OKB-165 and I960 in Alexei Isayev’s OKB-2. The main engine design bureau was that of Valentin Glushko, but he had no time for hydrogen-fuelled stages. In May 1961, Korolev contracted Lyulka to build a 25 tonne thrust engine and Isayev a small one of 7 tonne thrust. Within two years, they were able to come back to him with the specifications of their motors, called respectively the 11D54 and 11D56. However, their progress was slow. A critical factor was the lack of testing facilities. Although both tried to get the use of the main testing facility at Zagorsk, priority was given to the testing of military rockets. In the event, they were not able to conduct the necessary tests until 1966-7. By 1964, Korolev had abandoned hope of getting hydrogen-powered engines available on time for the N-1 and went for more conventional solutions.

By summer 1962, the N-1 approached a critical design review. The N-1 design was studied by a commission presided over by Mstislav Keldysh for two weeks in July 1962. The Keldysh Commission gave the go-ahead for the N-1, with Korolev’s choice of liquid oxygen and kerosene engines. Siddiqi [7] points to the significance of this decision, for it forever fractured the Soviet space programme into rival camps: Korolev’s OKB-1 on one side; and on the other, Glushko’s OKB-456 and Chelomei’s OKB-52. The payload was set at 75 tonnes, merging the N-1 and N-2 design concepts (another interpretation is that the N-2 was in effect renamed and superseded the N-1). Either way, 75 tonnes was now the base line.

Two months later, on 24th September 1962, a government decree called for a first test flight in 1965. The N-1 was once again given the green light. Despite these changes, the N-1 and its engines continued to make very slow progress. Promised funding never arrived and despite seven years of design and redesign, no hardware had yet been cut. When the Soviet Union began to respond to the challenge of Apollo, Korolev saw the moon landing as an opportunity to give the N-1 the prominence he believed it deserved. On 27th July 1963, Korolev wrote a memo confirming that the N-1 would now be directed toward a manned landing on the moon. Now that the nature of American lunar ambitions had became more apparent, the N-1 was directed away from Mars and toward the moon. His first ideas for a lunar mission for the N-1 were to use two N-1s for his manned lunar expedition, employing the technique of Earth orbit rendezvous. The precise point at which Korolev moved from the Earth orbit rendezvous profile to the lunar orbit rendezvous profile is unclear. Granted the difficulties they had experienced with getting funding for the N-1, the prospect of having to build only one, rather than two, for each moon mission must have been appealing. The favourable trajectory and payload economics of the American lunar orbit rendezvous method persuaded him that a single N-1 could do the job, but it would have to be upgraded again, this time from a payload of 75 tonnes to one of 92 to 95 tonnes, almost double its original intended payload.

When the decision to go to the moon was taken on 3rd August 1964, the N-1 was designated as the rocket for the lunar landing programme. The 95 tonne requirement had two immediate implications. First, the number of engines must be increased from 24 to 30, giving it a much wider base than had originally been intended. The 24 were in a ring and the additional six were added in the middle. Second, the fuel and oxidizer tanks would necessarily be very large. Korolev decided that spherical fuel tanks were to be used, eschewing the strapping of large fuel tanks to the side of the rocket. The diameters in each stage would be of different dimensions, making the system more complex and meaning that the rocket would be carrying a certain amount of empty space. The largest tank was no less than 12.8 m across! Korolev’s fuel tanks were so huge that they could not be transported by rail and had to be built on site at the cosmodrome. The first stage had 1,683 tonnes of propellant, of which no fewer than 20 tonnes were consumed before take-off!

Trying to get a 95-tonne payload out of a 75-tonne payload rocket design was quite a challenge. Other economies were sought and changes made:

• Setting a parking orbit of 220 km, lower than the 300 km originally planned.

• Additional cooling of fuels prior to launch.

• Thrust improvements of 2% in each engine.

• Use of plastic in place of steel in key components.

• Parking orbit inclination from 65° to 51.6° (later 50.7°).

• Reducing the crew of the lunar expedition from three to two.

Many different – and sometimes rival – branches and bureaux of the Soviet space industry were involved in the N-1 and the programme to put a Soviet cosmonaut on the moon. The N-1 was a huge industrial scientific undertaking, employing thousands

of people in Kyubyshev, Moscow, Dnepropetrovsk, Baikonour and many other locations. These were some of the main ones:

|

Builders of the N-l

|

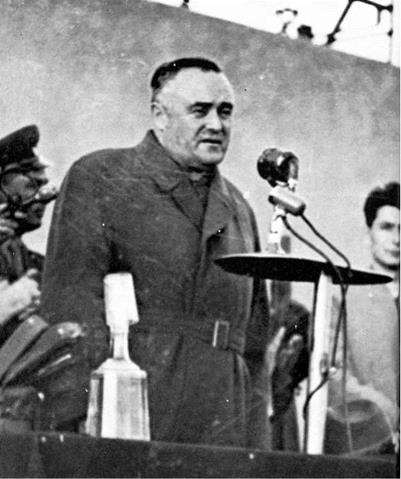

The overall designer was Sergei Kryukov, a graduate of the Moscow Higher Technical School, one of the experts sent to Germany in 1945 and a collaborator with Korolev on the R-7.