Carl E. McIlwain

Carl Edwin McIlwain was born on 26 March 1931 in Houston, Texas. He lived there during his primary and secondary school years except for the years 1942 to 1945, when his father was engaged in war work and the family lived in the states of Georgia and Kentucky.20

Showing an early aptitude for music, Carl obtained his first flute at age 10. By the time he reached high school—his family was back in Houston by that time—he was already an accomplished flutist, playing in both the school band and orchestra. During that period, he took lessons from the first flutist of the Houston Symphony Orchestra. Receiving a music scholarship at North Texas State College (now North Texas University), he spent the next four years there, obtaining his bachelor of music education degree in the spring of 1953.

During his undergraduate years at North Texas, he had an unusual experience in connection with his music training. His flute teacher, Professor George Morey, recognized a unique talent in him and served as a mentor in much the way that Van Allen did later in physics at Iowa. Carl found himself helping in teaching Morey’s students. By the time he was in his junior year, he had his own teaching studio similar to those of the teaching faculty members. He carried an active teaching load for his last two undergraduate years.

From an early age, Carl also developed a great interest and possessed a considerable natural aptitude in science. He remembers that by the time he was eight, he was often engaged with his chemistry and Erector sets. After the war, he went regularly to the army surplus stores to buy all kinds of electronic equipment for his tinkering. He took a number of high school courses in science. A physics teacher took a special interest in him and gave him the run of the laboratory, where he performed his own “play-experiments.” On one occasion, that teacher gave him an aptitude test and reported to Carl he had the highest score he had ever seen. When Carl later reported to him that he was going to North Texas to study music, the teacher expressed his surprise that he was not going into science. Carl responded, “Well,

I have a scholarship in music and none in science.” Reflecting his continuing interest in science, however, Carl also took the courses in geology, calculus, and noncalculus physics that North Texas offered.

Upon college graduation, Carl rejected several enticing high school band director’s offers and moved to Iowa City in early 1954 with his new bride, Mary, also a flutist. His initial goal was to study the physics of music. An academic position, to begin in the fall, had been arranged by his teacher and mentor in Texas, who was a former graduate of the Iowa Music Department. Carl discovered upon arrival, however, that he had been edged out of the paying teaching position by a graduating student who had decided to stay and join the Iowa faculty.21 Nevertheless, he promptly secured a chair as second flutist in the SUI orchestra, and he played with them during his first semester. However, he had to scramble to find paying work. Initially, Carl worked as a gas station attendant.

That summer, he was delighted by his employment as an hourly employee in the Physics Department’s Cosmic Ray Laboratory. One of his first tasks was to design and make a bracket to hold a large capacitor on one of the Deacon rocket circuit boards. This was his introduction to laboratory work on research instruments. It appeared to have been promising, as Van Allen gave him a research assistantship that fall.

In the academic arena, Carl signed up as a physics graduate student and enrolled in a set of undergraduate mathematics, chemistry, and physics courses to, as he put it, “get his feet on the ground.” Although his undergraduate work at Texas had not been in physics, at that time, Iowa’s only academic requirement to become a graduate student in any of its departments was to have a bachelor’s degree in any subject.

CHAPTER 2 • THE EARLY YEARS

Carl won his master’s and Ph. D. degrees in physics in June 1956 and June 1960, staying on at Iowa as an assistant professor for about a year and a half. He accepted an invitation in March 1961 to visit the campus of the University of California at San Diego, located at La Jolla, California. He and Mary were immediately taken by the research opportunities, location, and climate. They moved there, with Carl as a tenured associate professor, in February 1962. Appointed as a full professor in 1966, he continued his work there for the rest of his professional career. In addition to conducting a highly productive space research program, he served over the years in a number of important national advisory capacities.

Carl agreed to take on the development of the Loki rockoon for his master’s thesis. He later admitted that he had no appreciation whatever of the challenge that was presented by breaking into the space instrumentation business with no more electronics experience than he possessed.22 I still marvel that Carl was able to become so outstandingly effective in this work in such a short time.

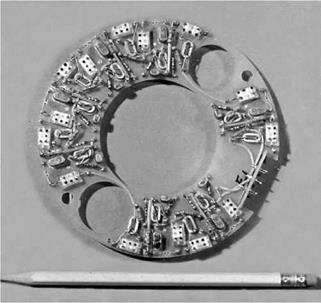

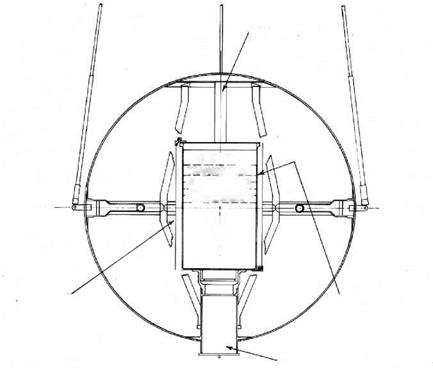

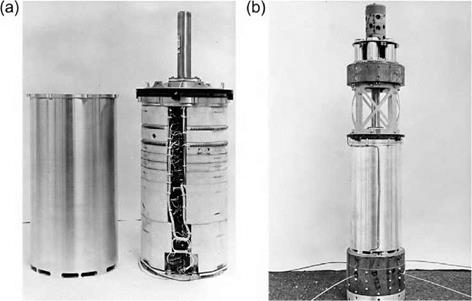

The instrument that Carl developed used a single GM counter to continue the high-latitude survey that had been the original goal of the Iowa rockoon program, that is, to learn more about the energy spectrum of the primary cosmic radiation by measuring its geomagnetic latitude dependence. The very high acceleration of the Loki rocket (270 times the Earth’s gravity [g], compared with 60 g for the Deacon rocket) presented a special design problem. Carl tested individual components to 1000 g in a centrifuge and conducted static load tests on an assembled payload to make sure that they would withstand the launching forces. The final instrument, of which several are seen in Figure 2.9, was a marvel of miniaturization, weighing only 6.8 pounds. He completed the design work and built a complement of 10 instrument payloads in time for the 1955 expedition. That was accomplished at very low cost— the funding provided by the National Science Foundation for designing and building the instruments and procuring the flight hardware was only $2000!23

The third goal of the 1955 expedition was to see if the basic rockoon technique could be extended to reach higher altitudes. Van Allen had envisioned a balloon – launched, two-stage Deacon-Loki rocket combination that might carry the instruments to great altitudes, perhaps as high as 180 miles. To test this concept, Carl Mcllwain mated a Loki I rocket (with his GM counter package) to the top of a Deacon rocket by means of a specially designed adapter. The whole assembly was to be carried to firing altitude by a much larger Skyhook balloon. Two such assemblies were prepared to test the concept, and to attempt to obtain the first ultra-high-altitude data.

The summer of 1955 was a hectic period, as we all worked in a near-frenzy to complete the flight hardware and supporting ground equipment. In addition to McDonald, Carl, and me, the overall construction and testing effort included a heavy workload in the

instrument shop and the capable and energetic help of very talented and dedicated student assistants and aides. Although Carl had his instruments in essentially complete form by the time they had to be shipped, Frank and I were further behind. We had to complete some of our final detector mounting, checkout, and calibrations later aboard the ship.

The field team consisted of Frank, Carl, Joe Kasper, and me. Frank served as the team leader, and Joe went as a general assistant, providing his invaluable help to the rest of us throughout the expedition.

That field expedition was a tremendously exciting and broadening experience and a highlight of my undergraduate years, but it did represent my first extended separation from my family since leaving the Air Force. Daughter Barbara was three, Sharon had just passed her second birthday, and Ros and I had just passed our fifth wedding anniversary.

I felt the strong desire to share this new experience with her. As no letters could be sent from the ship, I kept a fairly detailed diary, which I presented to her upon my return. That diary provided substantial information for this account. In addition to it and my other records, I drew upon published accounts by Carl McIlwain and Frank

CHAPTER 2 • THE EARLY YEARS 43

McDonald.24,25 Carl also kindly made his personal slides available, and Meredith’s unpublished notes provided further details.26

Joe and I, serving as an advance party, left from the Iowa City airport on a United Airlines DC-4 early on Tuesday, 13 September. Although I had accumulated many hours as a pilot in the Air Force, this was my first flight on a commercial airliner. That was in the more relaxed days before aircraft hijackings and terrorist attacks, and I was able to go into the cockpit to watch the pilots at their work. We had a few hours layover at Washington, D. C., and Joe and I hired a cab for a drive-by tour of many of the standard tourist attractions. We arrived at Norfolk, Virginia, late that afternoon and stayed overnight in a downtown hotel. The next morning, Joe called the port director for our ship’s location, and we went aboard.

It was the USS Ashland, a Landing Ship, Dock (LSD), with a 500 foot long open hold.27 The rear of its hold was closed by an immense watertight door that could be lowered to form a ramp. The whole ship could be lowered in the water by flooding the hold and ballast tanks. Smaller boats could then move into the hold, the gate could be closed, and the water in the hold and the ballast could be pumped out so that the ship with its load of boats could rise from its lowered position. The ship could then steam at normal speed while the captive craft could be serviced, outfitted, and loaded as needed. The mother ship was fitted with extensive machine shops, cranes, and other facilities for that purpose. Another wartime role for the LSDs was for amphibious landings, where flotillas of Landing Crafts, Assault (LCAs), Landing Ships, Tank (LSTs), and other craft could be carried in their flooded holds and disgorged at a beach. Thirty-one of these LSDs were built during World War II (WWII).

Ours, LSD-1, was the first one built, and the last one to remain in active service. It was powered by reciprocating steam engines rather than by the turbines that drove later models. A flat superstructure about 70 feet wide by 150 feet long, erected over the rear of the open hold to serve as a helicopter landing deck, served as our work platform for inflating and launching the rockoons. Although fully operational, old LSD-1 looked shopworn—I irreverently (and privately) rechristened it the USS Ashcan. Its primary mission on this trip was to carry supplies to Thule AFB in northern Greenland—our scientific expedition was accommodated as a secondary task.

As was customary for scientific expeditions aboard Navy ships, civilian scientists were accorded officer privileges and lived in officer’s quarters. Since Joe and I were the first of the scientists aboard, we had our pick of the available staterooms. We chose one on the bridge deck next to the officer’s wardroom. Our passageway led to the bridge, which served as a great vantage point for watching shipboard activities. I enjoyed those pleasures for only a short time, until the rest of the equipment and team arrived. As soon as that happened, I was completely absorbed during every waking

OPENING SPACE RESEARCH

hour with helping to set up our laboratory, completing our instruments, and launching the rockoons.

hour with helping to set up our laboratory, completing our instruments, and launching the rockoons.

During that initial slack period, Joe and I struck up a close friendship with Navy Commander Augustus (Gus) A. Ebel and Commander Bracken. Gus, a Ph. D. physicist assigned to the ONR, took care of all liaison matters between the scientific teams and the Navy, both on ship and on shore. Mr. Bracken was the ship’s executive officer. During the next several evenings, the two of them led us on evening shore excursions where we discovered the mysteries of nearby streets that boasted countless bars, arcades, and brothels, whose primary purpose was to relieve sailors of as much of their money as possible during their shore leaves.

Our equipment arrived and was hoisted aboard on Thursday. The batteries for our instruments were appropriately stowed in the battery-charging room, and the rockets were placed in the ammunition magazine. Joe and I took over a large room belowdecks to serve as a shipboard laboratory, and we began setting up our equipment. We also began searching for a suitable additional room to serve as a darkroom for developing the film from our ground data recorder.

Ed Lewis and Herbert Ballman from Winzen Research, along with a General Mills observer, arrived that day. Winzen Research, with Lewis in charge, conducted that expedition’s balloon operations.

Frank and Carl also arrived late that Thursday night. The next morning Carl discovered, to his great dismay, that some of the Loki rockets had been shipped with one inch stub fins suitable only for low-altitude launches. He had asked when ordering them that they be fitted with larger fins to assure stability during the high-altitude launches, but that request had been ignored. Frank and Carl made an emergency trip to a Norfolk hardware store for sheet aluminum, returned, cut appropriately sized fins, and screwed them onto the rocket’s stub fins. They worked!

Two NRL rockoon-launching groups also accompanied this expedition. Les Meredith by that time had joined NRL and set up his own research program there. His instruments were also designed to further study the auroral soft radiation. Accompanying Les were Leonard (Leo) R. Davis and Howard M. Caulk. The NRL also fielded an optics group led by James (Jim) E. Kupperian Jr. and accompanied by Robert (Bob) W. Kreplin. The trailer that supported both NRL groups arrived on Friday and was hoisted aboard and firmly anchored on a corner of the flight deck. I marveled at the ease with which their trailer-based laboratory was put in operation—as soon as it was connected to electrical power, they were in business. Because of the simplicity of that process, the NRL groups were able to relax and enjoy pleasant hours with the ship’s crew for several days, while Frank and I labored to set up our laboratory belowdecks.

The helium also arrived on Friday—I was impressed by the large number of helium bottles required. At that time, virtually all the helium in the United States was being

|

CHAPTER 2 • THE EARLY YEARS

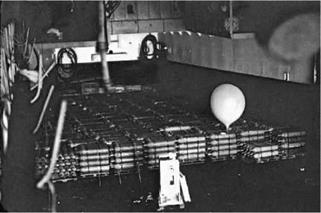

FIGURE 2.10 More than 1400 cylinders of helium were stacked in the hull of the ship for the summer 1955 rockoon expedition. About half a dozen pallets of 16 cylinders each were shifted into a position below the helicopter deck for each balloon inflation. There they were interconnected by a manifold to provide the necessary flow rate and volume. This picture was taken while the ship was under way, when a small balloon was being inflated to be tethered above the ship as a wind-direction indicator. (Courtesy of Carl E. McIlwain.) |

produced at a single plant in Texas. I was told that our balloon expeditions used a substantial portion of the then-current worldwide production capacity. The bottles were stowed in the ship’s massive hull, as depicted in Figure 2.10.

That evening, we were invited to the Captain’s presailing cocktail party. This was our first opportunity to talk at length with Captain Bryce, who was wonderfully accommodating and helpful throughout the entire expedition.

Frank and I ran into our first serious problem on Saturday as we were trying to get our ground station in operation. The ship’s primary electrical power was direct current—there was very limited alternating current (AC) power. Of course, all of our laboratory equipment required AC. Although an AC power receptacle had been found on deck for the NRL trailer, there was none in or near our laboratory. Our extension cords were not heavy enough to carry the load from any available source. Joe and I made an emergency trip to a Norfolk hardware store to buy enough AWG #8 residential service cable to make a super extension cable. The crew installed it for us—for an easily negotiated price of six rolls of Scotch-brand electrical tape. We were able to complete the installation of the laboratory equipment and receiving station on that day and immediately started on the final assembly and calibration of our instruments.

At that point, we had another major interruption—Hurricane Ione was heading straight for us. On Saturday evening, our ship, along with more than 80 other Navy ships, put out for hurricane anchorage in the middle of the Chesapeake Bay. As the ship

OPENING SPACE RESEARCH

![]() steered with its head into the wind throughout the blow, there was surprisingly little rolling or pitching. This interlude gave Frank, Carl, and me more time to continue the work on our instruments. We rode out the storm’s near-approach for the next several days, returning to the Norfolk area on Tuesday. The hurricane turned out to be a relatively mild one, and no significant damage was done to ships or other Navy facilities.

steered with its head into the wind throughout the blow, there was surprisingly little rolling or pitching. This interlude gave Frank, Carl, and me more time to continue the work on our instruments. We rode out the storm’s near-approach for the next several days, returning to the Norfolk area on Tuesday. The hurricane turned out to be a relatively mild one, and no significant damage was done to ships or other Navy facilities.

By Wednesday, 21 September, the water was calm, the sky was clear and blue, and the crew was able to complete the ship’s loading and fueling. We made way for the ocean that afternoon. By then, Frank and I had completed work on 4 of our 10 instrument packages. Once we reached the open ocean and began experiencing a 10 degree roll with some pitching, we began to appreciate the difficulties in working in the ship’s cramped and wildly gyrating quarters. The demanding precision work became remarkably inefficient. Nevertheless, we made reasonable progress.

Thursday night, we paused to rendezvous with a coast guard cutter near Woods Hole, Cape Cod. One of the ship’s radar men had had an acute attack of appendicitis. He was very fortunate that it happened there rather than later, as there was no doctor aboard.

On Friday, 23 September, at about 4:00 PM, off the lower tip of Nova Scotia, we sent off the first rockoon, one of Carl Mcllwain’s Lokis. It was a success in every way—the first time that the initial shot on one of these expeditions had worked properly. I manned our receiving antenna located on the roof of the NRL trailer during the ascent and reported my sighting of the visible trail when the rocket fired. We determined later that it had fired at 72,000 feet and climbed to about 230,000 feet altitude. Although the signal was lost for a moment at the time of ignition, Carl soon retuned the receiver to a slightly shifted frequency. Once acquired, the signal remained strong throughout the rest of the flight. Carl was elated by his early success. Of course, this far south, the auroral soft radiation was not seen, nor expected.

By that time, Frank and I had six of our Deacon instruments completely checked and ready to go. The next day, Saturday, we launched the first of them. Figure 2.11 shows the balloon preparation for a typical launch. My diary entry for that event provides a summary of the process, and clearly reflects the elation of a proud young university student experiencing his first successful field launch:

Success! The exuberance of first success! Today we fired a Deacon. We got a very good cosmic ray record. The auroral effect was not found, but we didn’t expect it this far south. The main thing is that the equipment has been proven OK. It’s a wonderful feeling when something you’ve lived with closely for so many months works as planned. I’ve done more working, planning, sweating, and worrying about this project than any I’ve tried before. But when the sound of the subcarrier oscillators, modulated as they should be, comes over the receiver, and the Brush recorder keeps on writing down the data, it is all worth it.

|

|

CHAPTER 2 • THE EARLY YEARS

When I went to bed last night, the plans were laid. We were scheduled to fire at 10:00 this morning. So, for a change, this morning I was up bright and early at 6:45 for breakfast. Breakfast consisted of scrambled eggs, sausage, toast, and three cups of coffee. The companionship of the other scientists (that is what they call us aboard ship) is very pleasant and gratifying. It is great to sit around the table and sip coffee while talking over problems and plans.

After breakfast, Frank and I went down to our recording station. We started putting the rocket head that we intended to use through its final paces. There is the checking of counting rates, the calibration of the system for recording pulse heights, the checking of battery voltages as the instrument operates on its own power, the readying of the recording equipment, and finally, the cone is slipped over the equipment and tightened by its 18 screws. The cone is now sealed and operating, not to be opened again.

Meanwhile, the people on the launching deck have been working. Joe [Kasper] and Mr. [.sic: Commander] Ebel have been putting the fins on the rocket, arming it, attaching the firing box, and placing the bag over the rocket. The Winzen Research people have been inflating the 75 foot diameter balloon in preparation for the launch.

After the head [instrumented payload] was sealed, Frank carried it up and they attached it to the rocket. I remained at the recording station to keep a check on it. I noticed noise on the channels at times, and variations of signal strength. I tried to have someone up on the deck check on it (we have telephone communication between recording station, van, and antenna) but there I learned one lesson. When a launching goes that far, it is almost impossible to interrupt it. The balloon is already partly inflated and the only way to abort or delay a launching is simply to cut the balloon loose and start over from scratch. Since the equipment was working a little we decided to go ahead.

Finally came the word—cut loose—the rocket was on its own. Then began the scramble to find out what was causing the trouble. (Our setup used the antenna, preamplifier, and receiver on the NRL trailer on deck, with a line passing the signal from the trailer to the remaining equipment in our laboratory belowdecks.) First of all, they discovered that something was

OPENING SPACE RESEARCH

![]() wrong with the preamplifier. That still did not cure the trouble, but soon we decided that the trouble was not in the rocket, but rather with the NRL equipment in the trailer. We had our own receiver standing by down in our recording station, so we bypassed all NRL equipment, going directly from antenna down to our receiver. Success! There was still a loose connection somewhere, causing occasional interference, but not serious. It didn’t foul up more than a few seconds of data.

wrong with the preamplifier. That still did not cure the trouble, but soon we decided that the trouble was not in the rocket, but rather with the NRL equipment in the trailer. We had our own receiver standing by down in our recording station, so we bypassed all NRL equipment, going directly from antenna down to our receiver. Success! There was still a loose connection somewhere, causing occasional interference, but not serious. It didn’t foul up more than a few seconds of data.

The balloon ascent took about an hour and a half. Finally, at about 70,000 feet, the Racon quit, our frequency shifted slightly, and the rocket was off. The rocket flight lasted four and one-half minutes, during which time there was a constant scurry, to check everything (the recording of the signal), check time on the chronograph, etc., etc.

Finally, the signal faded out quickly, there was nothing but noise on the Brush recorders, and the flight was over. The rocket, its nose assembly containing months of labor, and all that beautiful electronic equipment, was deep in the sea. But we have 200 feet of paper and 100 feet of film that testify to the fact that it was well spent.

The signal strength remained above 100 microvolts during the balloon ascent and above 5 microvolts during the rocket flight, except when they were aiming the antenna. Since we had made such a quick changeover on the receivers, the meter for directing the person aiming the antenna could not be connected, and orders had to be given orally. This doesn’t work too well, so we have that fixed now. We installed a line to operate the meter.

We had been somewhat concerned about the subcarrier frequencies. Before leaving home, I discovered a strong dependence of frequency on filament voltage. But all during the flight, until rocket firing, they held steady. After firing, I was too busy worrying about other things to look, but I’m sure they are OK. At least the information came over them and that is the final criterion.28

That same day we got off another of Carl’s Lokis—also a success. Sunday we passed over the Grand Banks east of Newfoundland. In the relatively shallow water, the seas were still showing the effects of Hurricane Ione that had preceded us up the coast. The USS Ashland was, to say the least, not well suited for rough weather. With its broad bottom, it took up a wild rolling and pitching motion. At times, the ship would seem to remain poised on one of its sides for a few moments, and then over we would go with a sickening whop to the other side. Throughout the night, we heard lockers and other gear crashing and banging in the passageways. Most of the scientists and many of the crew were seasick, but fortunately, I escaped that indignity. By wedging myself between the front rail and rear of my bunk, I was even able to get a reasonable night’s rest. Figure 2.12 shows a sample of the tricky inflation exercise near the Grand Banks.

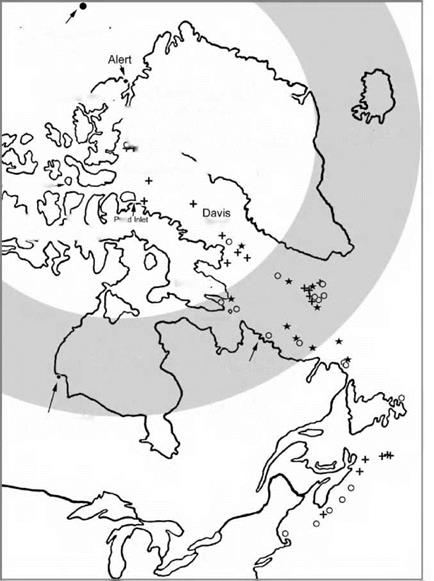

Soon after passing to the north of Newfoundland, the swells abated, the weather began to turn colder, and I broke out my parka. Rockoon launching soon settled into a busy but purposeful routine as we proceeded farther north. Since Carl’s scientific objective was a comprehensive latitude survey of the primary cosmic rays, he spread his flights out en route through the Davis Strait between 43 degrees and 73 degrees north geographic latitude (about 54 degrees to 84 degrees north geomagnetic latitude). In contrast, the primary objective of the Deacon flights (except for the early shakedown launch) was to study the auroral soft radiation. We launched the rest of our instruments

|

CHAPTER 2 • THE EARLY YEARS

FIGURE 2.12 Filling a balloon under adverse conditions. On Sunday, 25 September, we launched another of Carl’s Loki rockoons (it experienced igniter failure). That operation was conducted over the Grand Banks, where the effects of Hurricane Ione were still evident. The ship’s roll was about 15 degrees when this picture was taken. That represented the limit of our ability to conduct launches. During that night, the roll peaked at over 40 degrees, according to the ship’s log. (Courtesy of Carl E. McIlwain.) |

between 57 degrees and 68 degrees north geographic latitude (68 degrees to 79 degrees north geomagnetic latitude).

The second Deacon rockoon was launched on Tuesday afternoon, 27 September, at a geomagnetic latitude of about 69 degrees. Everything worked well, and we saw a large flux of auroral soft radiation—the counting rate was about seven times the rate that it would have been without the auroral radiation. Three other attempts were made by other groups that day, but unfortunately, they all failed. On one by Les Meredith’s NRL group, the rocket fired, but the flight data turned out to be unusable. In the attempt by Kupperian’s NRL group, the rocket failed to fire. During Carl’s next Loki attempt, his GM counter went into continuous discharge, so that he received no useful data.

The elaborate traditional initiation into Ye Royal Order of the Blue Nose for our first crossing of the Arctic Circle was also held on that day. Since it took place when Frank, Gus Ebel, and I were busily preparing for our launch, we were excused from that boisterous and disgustingly messy rite of passage. I was delighted that we received our certificates anyway!

The pace of our operations peaked during the next two days, with three more flights by Frank and me (all three successful), one each by the two NRL groups (both failures), and the flights of both of our two-stage rockoons (also failures). The auroral effect was seen again in Frank’s and my second and third flights, a 2.5 times normal effect at about 72 degrees geomagnetic latitude and a 2 times effect at 76 degrees. On the fourth flight at about 78 degrees north geomagnetic latitude, we saw no excess radiation and surmised that we were too far north to observe it. We decided to hold

|

OPENING SPACE RESEARCH

the remaining five Deacons for the return trip and concentrated on completing the final preparation of the remaining instruments during the rest of the northbound trip.

The prospect for reaching an unprecedented high altitude with small two-stage rockets was an exciting one.29 The field operation, however, was risky. Frank, Carl, and I still shudder when we think about it, especially in the light of the later accidental misfiring of a Loki rocket on the ship’s deck. We had limited means for assembling the tall two-stage configuration on the ship, as its combined height was more than 17 feet. As seen in Figure 2.13, we used the NRL trailer and a stepladder as our “gantry,” first setting the Deacon rocket (with its igniter in place but not connected) vertically on the deck, then carefully mating the Loki rocket (also with its igniter installed) atop the Deacon-Loki adapter.

CHAPTER 2 • THE EARLY YEARS 51

Then came the perilous task of moving the nearly 200 pound assembly across about 75 feet of deck to position it directly under the, by then, inflated and tethered balloon. Since we had no suitable wheeled conveyance, several of us encircled the Deacon rocket with our arms and, with the Loki teetering above, manhandled the assembly across the deck.

Once under the balloon, the Loki’s firing lanyard was attached to the top of the Deacon. Its function was to ignite the Loki once the Deacon had completed its burn and differential atmospheric drag had separated the two rockets. For safety’s sake, barometric pressure and acceleration-activated switches were included to prevent the Loki from firing until it reached altitude, and until after the Deacon had fired. The Deacon firing box was tied by its cord to the bottom of the Deacon’s tail fins and connected to the igniter.

At that point, the balloon’s tether was reeled out so that it could take up the slack on the load line, and then the whole assembly was released. The balloon carried the multistage rocket to its launch altitude.

In the first attempt, the Deacon rocket fired, but there was no second-stage ignition. Carl surmised that he had made the fit of the adapter between the top of the Deacon and the Loki rocket nozzle too tight, so that the two stages did not drift apart. With a file, he reduced the diameter of the coupling for the second attempt. On that attempt, the balloon ascended and both the Deacon firing and Loki ignition were normal. The GM counter operated properly initially, but two and a half seconds after Loki ignition, the transmitted signal was strongly modulated by noise for about a second, and then ceased altogether.

After Carl returned home, he mentioned this attempt to one of the engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who responded, “Why didn’t you tell us what you were going to do? We would have told you that the thin aluminum nose cone would melt.” After some confirmatory calculations, Carl and Van realized that they had grossly underestimated the aerodynamic heating of the Loki’s aluminum nose cone at its initial flight velocity of greater than 5000 miles per hour, and the nose cone and instruments probably did melt.

Van Allen stated later, “It is probable that an inexpensive two-stage rockoon can be made to carry small payloads (~7 lb.) to summit altitudes of over 1,000,000 ft. [about 190 miles] if temperature-resistant materials (e. g. stainless steel) are used for the nose cone and the tail fins of the second stage.”30 Van Allen also stated, “Retrospectively, it appears likely that this inexpensive technique, given a heat – resistant nose cone, would have resulted in discovery of the geomagnetically trapped radiation.”31

No further attempts were ever made with that configuration. The Van Allen Radiation Belt discovery had to wait for two and a half more years for the flight of the Explorer I and III satellites.

OPENING SPACE RESEARCH

![]() The voyage continued. After passing a steady parade of icebergs for several days, we reached Thule on the northwest coast of Greenland on Saturday morning, the first day of October. We were presented with a frigid and barren-looking scene, with not a tree in sight. This sizable military outpost was spread out on gently sloping land between the indentation of the bay and background hills to the south. The dominant color was brown, with a few snow banks still showing on the northern slopes of the hills. Being just past fall equinox, the Sun crept low across the southern horizon during the day and just beyond the northern horizon during the lengthening night.

The voyage continued. After passing a steady parade of icebergs for several days, we reached Thule on the northwest coast of Greenland on Saturday morning, the first day of October. We were presented with a frigid and barren-looking scene, with not a tree in sight. This sizable military outpost was spread out on gently sloping land between the indentation of the bay and background hills to the south. The dominant color was brown, with a few snow banks still showing on the northern slopes of the hills. Being just past fall equinox, the Sun crept low across the southern horizon during the day and just beyond the northern horizon during the lengthening night.

Even today, whenever I look at a globe, I am impressed anew by how far north Thule lies. It is above 76 degrees north geographic latitude—about 400 miles more northerly than Point Barrow and Barter Island on the northern coast of Alaska, and only a little more than 1600 miles below the North Pole.

Since Frank and I had completed the preparation of our remaining Deacon instruments by that time, and there was a large enough crew without me to handle the rest of the launches, I left the expedition at Thule for Iowa City to return to the classes that would complete my undergraduate studies. Les Meredith also needed to return for a White Sands rocket launch. We hitched a ride on an Air Force C-54 and made an uneventful trip stateside. Arriving back in Iowa City on Tuesday, 4 October, I was over two weeks late in starting my fall classes (advanced calculus, differential equations, modern physics, and electricity and magnetism). I struggled mightily throughout the rest of the semester to try to catch up but was never able to do so to my satisfaction.

On the ship, Carl still had three of his Loki rockets to launch, and Frank had five more of our Deacons. The ship’s first order of business, however, was to make a side trip to Pond Inlet on the north end of Baffin Island to pick up a Catholic priest. Frank, Carl, and Joe were told that he had “lost his mind over the local custom of slipping unwanted girl babies under the ice.”

Shortly out of Pond Inlet, on 4 October, Carl made another successful Loki launch. Two days later, Frank successfully launched another Deacon rockoon. After several days’ stop at Frobisher Bay to drop off supplies, Frank continued with the launching of the remaining four of our Deacon rockoons as the ship progressed again through the auroral zone. Two of those were successful and provided good data on the auroral soft radiation, but two rockets failed to ignite.

Carl’s next attempt resulted in a highly disturbing and potentially tragic incident, the unexpected ignition of a Loki rocket on the ship’s deck. By Frank McDonald’s account:

A Loki rocket ignited in its horizontal cradle as the ONR representative, G. Ebel, was adjusting the backup timers in the control box that was suspended below the rocket. The rocket struck a stack of helium tanks and exploded, covering the deck with smoke and debris.

CHAPTER 2 • THE EARLY YEARS

Ebel’s face was badly burned. The ship had a medical corpsman but no doctor so we headed for the nearest port. Ebel had a rapid and complete recovery. I returned via Washington to receive the full wrath of ONR for what had already been a traumatic and unsettling event. In a test at Iowa, C. McIlwain found that the length of the wires connecting the rocket [igniter] to the control box was such as to probably produce standing waves, and trigger the igniter.32

Carl added further details. His tests upon returning to Iowa showed that the transmitter in his instrument package probably induced a current in excess of 0.2 amperes in the igniter wires, and that was enough to set off the rocket. Parenthetically, he mentioned that this had been his “best” transmitter, having been tuned to produce the greatest output power of all of his instruments.33

The less than one second normal burning of the rocket was essentially a controlled explosion. The blast centered on Gus Ebel’s shoulder, where it burned through his thick clothing and embedded bits of igniter wire in his flesh. Joe Kasper was standing nearby, and his eardrums were ruptured, his coat was blown off, and bits of propellant were embedded in his lips and face. Carl was about six feet to one side and suffered only mild noise trauma. As the rocket accelerated, its sharp fins sliced through the three-quarter inch thick plywood brackets that formed its supporting cradle, then snipped the phone wire draped from the headset of the sailor who was serving as the talker in contact with the bridge. He took an instinctive giant leap backward and landed, luckily, in a gun turret adjacent to the flight deck rather than in the icy sea. By the time the rocket had traveled about 50 feet and struck the stack of empty helium cylinders, it had already reached supersonic speed. Upon impact, the rocket exploded, spreading parts of the rocket, flight instrument, and burning propellant over the entire ship.

Captain Bryce immediately ordered that the remaining Loki rocket be dumped overboard, but Carl saved his remaining highly prized instrumented payload. The scientific work was terminated, and the ship proceeded as quickly as possible to St. Johns, Newfoundland, to get medical attention for Gus Ebel. The ship returned to port at Norfolk in mid-October without further incident.

Carl’s tenth rocket instrument was put to good use later. On the morning of 23 February 1956, a breathless call from John Simpson at the University of Chicago stated that a gigantic solar storm was bombarding the Earth with cosmic rays. Carl hurriedly attached his unused payload to a cluster of rubber balloons and launched it from the university’s athletic field, and it reached peak altitude about 17 hours after the onset of the storm. Too late for the main event, the rig found that solar cosmic rays were still adding about 40 percent to the expected galactic cosmic ray counting rate. That event served as the subject for Carl’s first published paper.34

OPENING SPACE RESEARCH

![]() I was elated by the expedition’s success. Frank’s and my instruments operated perfectly on all 10 flights. Eight of the 10 flights reached their expected altitude and provided useful data. Carl’s success rate was excellent for the first field trial of a new rocket, with four successes out of the six single-stage attempts. Those flights provided the basis for Carl’s master’s thesis.35 The NRL flights were more disappointing. Both of Jim Kupperian’s attempts failed, and Les Meredith was successful with only two of his six attempts.

I was elated by the expedition’s success. Frank’s and my instruments operated perfectly on all 10 flights. Eight of the 10 flights reached their expected altitude and provided useful data. Carl’s success rate was excellent for the first field trial of a new rocket, with four successes out of the six single-stage attempts. Those flights provided the basis for Carl’s master’s thesis.35 The NRL flights were more disappointing. Both of Jim Kupperian’s attempts failed, and Les Meredith was successful with only two of his six attempts.

This record solidly established the Loki rocket as a viable carrier for rockoon launches. After honorable service during four shipboard expeditions, the Deacon rocket was retired as a rockoon component at the end of the 1955 campaign. An improved version of the Loki rocket (Loki Phase II) was used exclusively on the later Iowa rockoon expeditions.

OPENING SPACE RESEARCH

OPENING SPACE RESEARCH

great confidence in their work and led, eventually, to the collaborative arrangement whereby they designed the high-voltage power supplies for the GM counters and supplied component parts kits that we assembled in the early Explorers.

great confidence in their work and led, eventually, to the collaborative arrangement whereby they designed the high-voltage power supplies for the GM counters and supplied component parts kits that we assembled in the early Explorers.

PACKAGE

PACKAGE

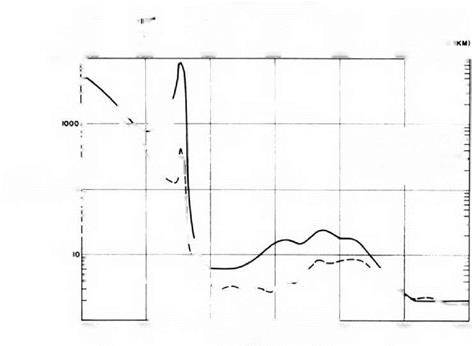

FIGURE 13.6 A plot of data from the two GM counters on Explorer IV, taken about 3.5 hours after the Argus I burst on 27 August 1958. (Courtesy of the University Archives, Papers of James A. Van Allen, Department of Special Collections, University of Iowa Libraries.)

FIGURE 13.6 A plot of data from the two GM counters on Explorer IV, taken about 3.5 hours after the Argus I burst on 27 August 1958. (Courtesy of the University Archives, Papers of James A. Van Allen, Department of Special Collections, University of Iowa Libraries.)

OPENING SPACE RESEARCH

OPENING SPACE RESEARCH

CHAPTER 2 • THE EARLY YEARS

CHAPTER 2 • THE EARLY YEARS