As mentioned earlier, everyone in the airline industry fully expected to see the start of supersonic airliner service by the end of the 1960s. Both Boeing and Lockheed had impressive multi-hundred-passenger designs on the drawing boards; with the Boeing 2707 featuring a variable-geometry swing wing, and Lockheed’s Model 2000 showing a raked double-delta planform. Both these mammoth machines echoed the lines of North American’s radical six-engine XB-70 Valkyrie Mach 3 strategic bomber, which first flew in 1964. Unlike the Valkyrie, however, neither U. S. commercial Supersonic Transport (SST) ever made it past the mockup stage.

As public awareness of environmental problems associated with SSTs rapidly grew, the airplanes began to experience a reversal of fortunes. Provisional orders from the world’s major airlines fell by the wayside as the rising drumbeat for ending America’s SST development became too loud to ignore. In 1971, the Nixon Administration officially brought the U. S. Supersonic Transport program to a halt. Public concerns about the negative impact of such an aircraft, with its jarring sonic booms supposedly killing wildlife and high-altitude exhaust eroding the ozone layer, completely overshadowed whatever speed advantages any SST would be able to offer for a very small percentage of the traveling public. The factors of economics and passenger capacity won out over speed and technical supremacy once again.

That same year in Europe, however, a graceful and elegant-looking new airplane took to the air called simply, Concorde, the world’s first and only successful supersonic airliner. Great Britain and France realized a decades-long dream to develop and fly such an aircraft, having studied the idea of a European-built SST as early

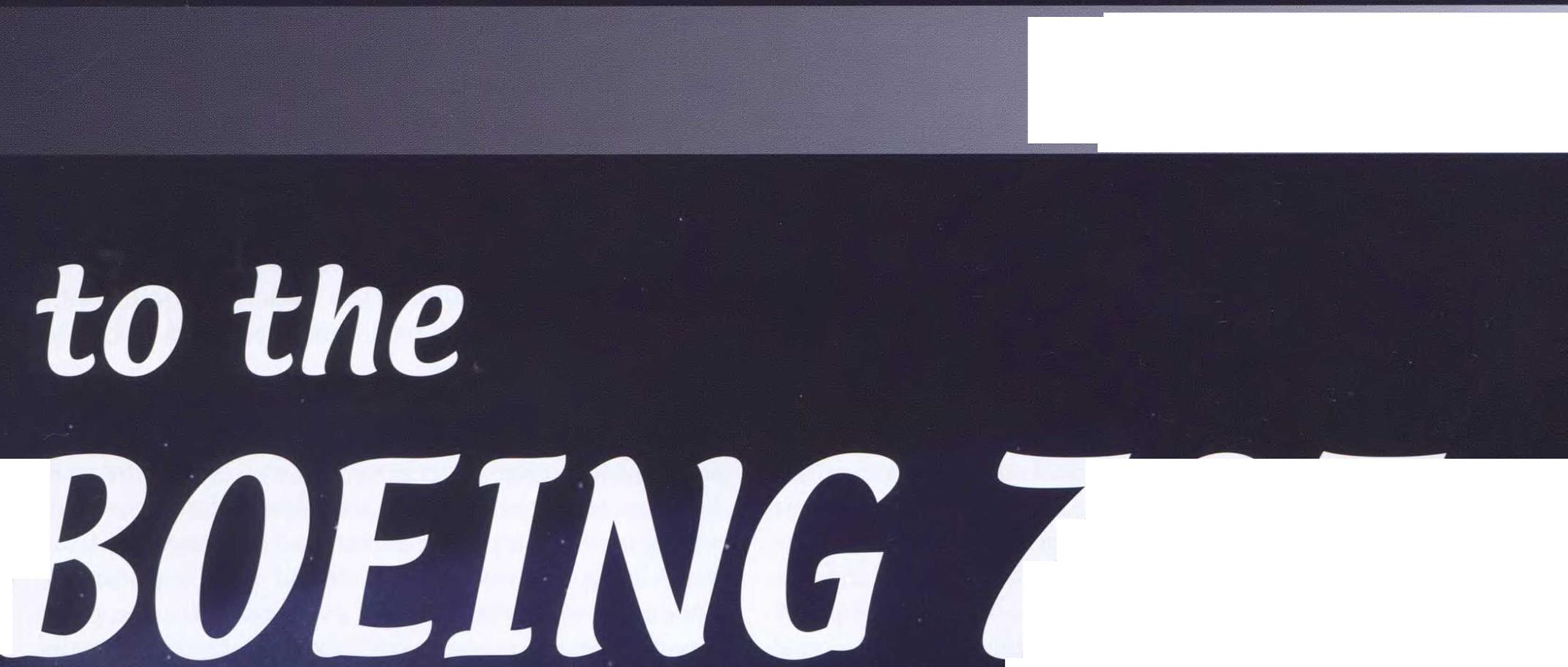

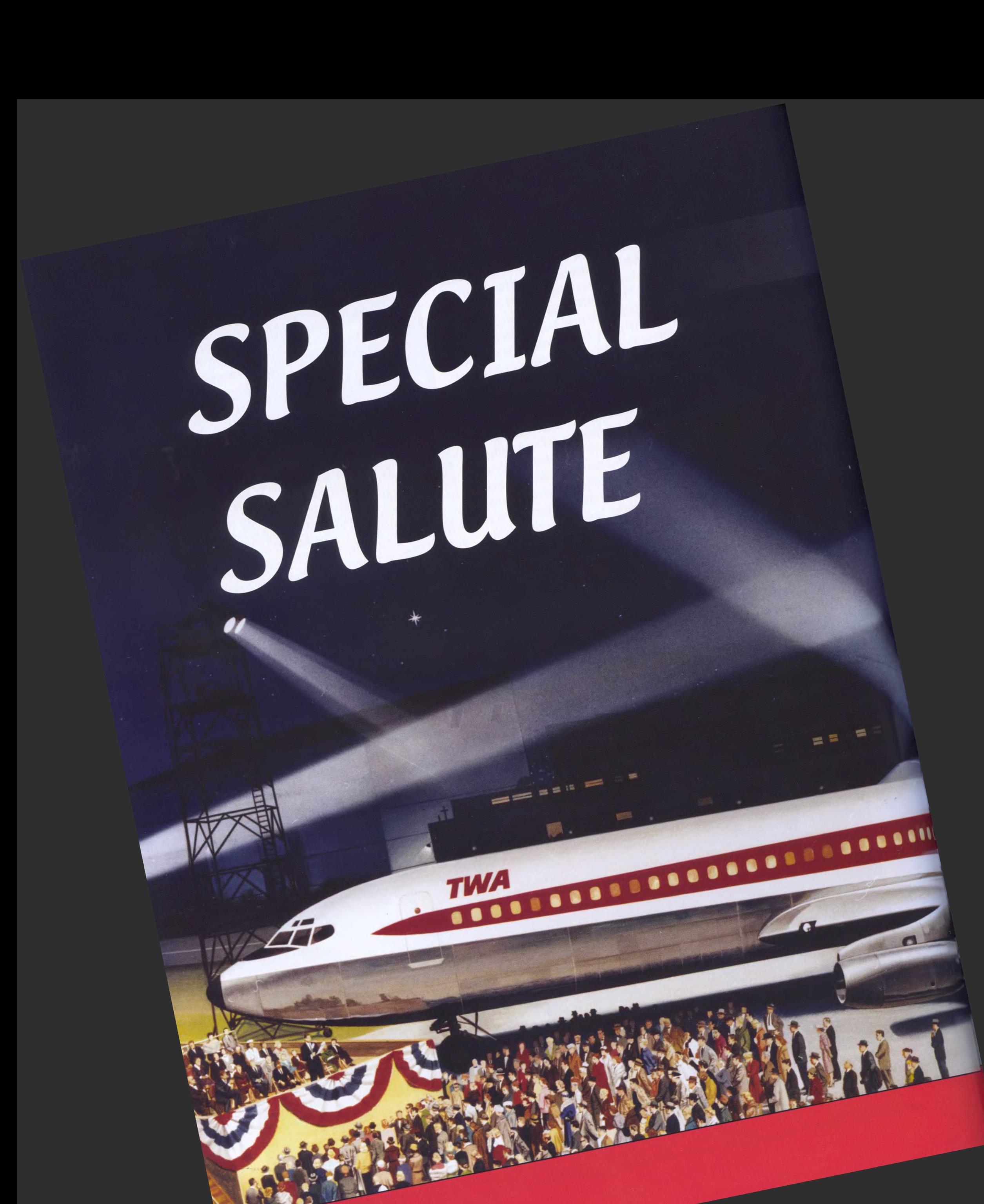

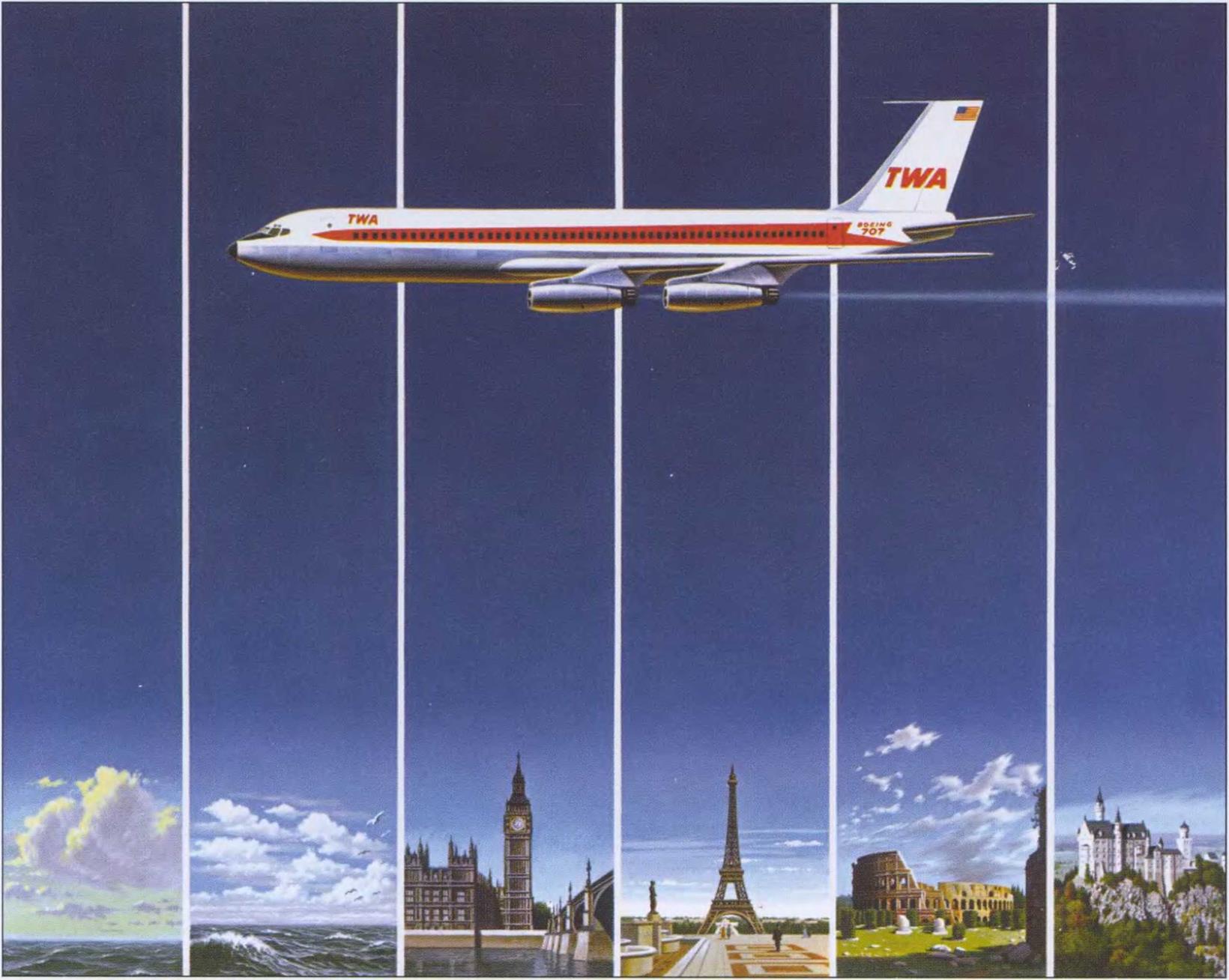

The work of one of the true masters of modern American^illustration, this

The work of one of the true masters of modern American^illustration, this

к ттлшяш v&o* ^

epic Ren Wicks painting shows an imaginary inaugural gala for TWA’s majestic new 707 complete with Hollywood premier searchlights.

n remembering the seemingly magical time when jet airliners first entered commercial service in October 1958, it is important to note that for the better part of the first year of operations, there was only one U. S.-built jet airliner flying, and only three U. S. flag or domestic carriers using it. That airplane was the Boeing 707. Hence, if you were standing on an observation deck at New York, Los Angeles, Paris, or London, this would be the only American jetliner you would ever see. Moreover, in certain U. S. cities celebrating the beginning of jet service at the time, there might be only one airline flying there in a 707.

For those of us standing by an airport chain-link fence in 1959, watching landing approaches on Aviation Boulevard at LAX in California or Rockaway Boulevard at New York’s Idlewild, the scenario might be something like this: Seeing a four – engine propliner with red-white-and-blue propeller tips gleaming in the afternoon sunlight would signal the approach of a United Air Lines DC-7 Mainliner. Next would be a red-striped triple-tail Trans World Airlines Super-G Constellation, followed by a regional airline’s twin-engine Convair Liner. All typical fare for dedicated airport brethren of the time.

Then, someone in the crowd would excitedly exclaim, “Look, there’s a jet!” Wisps of smoke on the horizon would signal the approach of a jetliner that could only be a brand-new Boeing 707. Would the plane belong to Pan American, TWA, or American Airlines? As the aircraft came into view, the bright red – orange nose of the latter airline became visible, and soon, all 135,000 pounds of sleek bare-metal whistling tonnage would scream overhead with the wail of a thousand banshees. Unlike the national mood only a few years later, no one ever seemed to mind the noise. After all, it was a jet.

During a typical afternoon of airplane spotting, one might see only one or two 707s for every ten or twelve propliners, but the experience was well worth the wait. Another new sound often accompanied these swept – wing giants as they soared overhead only seconds from touchdown. It was an eerie sound with a ghost-like “wooosh” that would linger overhead after the plane flew by, and then, just as quickly as it appeared, would swiftly dissipate. On cloudy days you could actually see the cyclonic tube of air that created this sound. It was the turbulent vortices emanating from the jetliner’s wingtips as they sliced through the air at then-unheard – of approach speeds of nearly 150 mph.

|

…this magnificent new Jet airplane. Yes, this is the newest, largest,

and fastest Jetliner in the skies today. And its longer range assures non-stop flights over the Atlantic —in both directions. Even on the ground, every line of the TWA пшкомтшиш BOEING 707 — inspires confidence… and tells you here is the ultimate in travel speed and comfort. You notice at once the swept back wings… the absence of propellers on the four great pure jet engines and above all —the majestic size of this totally different plane!

|

|

Another facet of this new era in transportation was the marketing of these airplanes to the general public. Dramatic artwork and vivid color photography was incorporated into new brochures produced to create a sense of excitement and glamor for this dramatic new mode of air travel. Reflecting the 1950’s genre of commercial illustration, images of cavernous passenger cabins occupied by handsome, well-dressed men and stylish women graced the pages of these brochures. Illustrations or photos of lavishly prepared foods being served to attractive passengers flying in the sumptuous cabin of a new jetliner conjured up images of elegant dining aloft while flying in the stratosphere at close to the speed of sound.

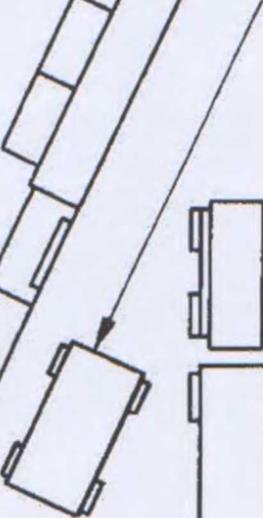

As mentioned earlier, one of the premier American illustrators of the day was Ren Wicks, founder of the world-renowned commercial art studio, Group West. As personal artist to TWA’s Howard Hughes, Wicks was tasked with creating the trend-setting artwork that brought TWA’s Boeing 707 to life years before the airplane entered passenger service. Wicks flew to all of TWA’s major cities and photographed their respective skylines and cityscapes from helicopters to acquire the detailed reference material deemed so essential in achieving the realism seen in his artwork.

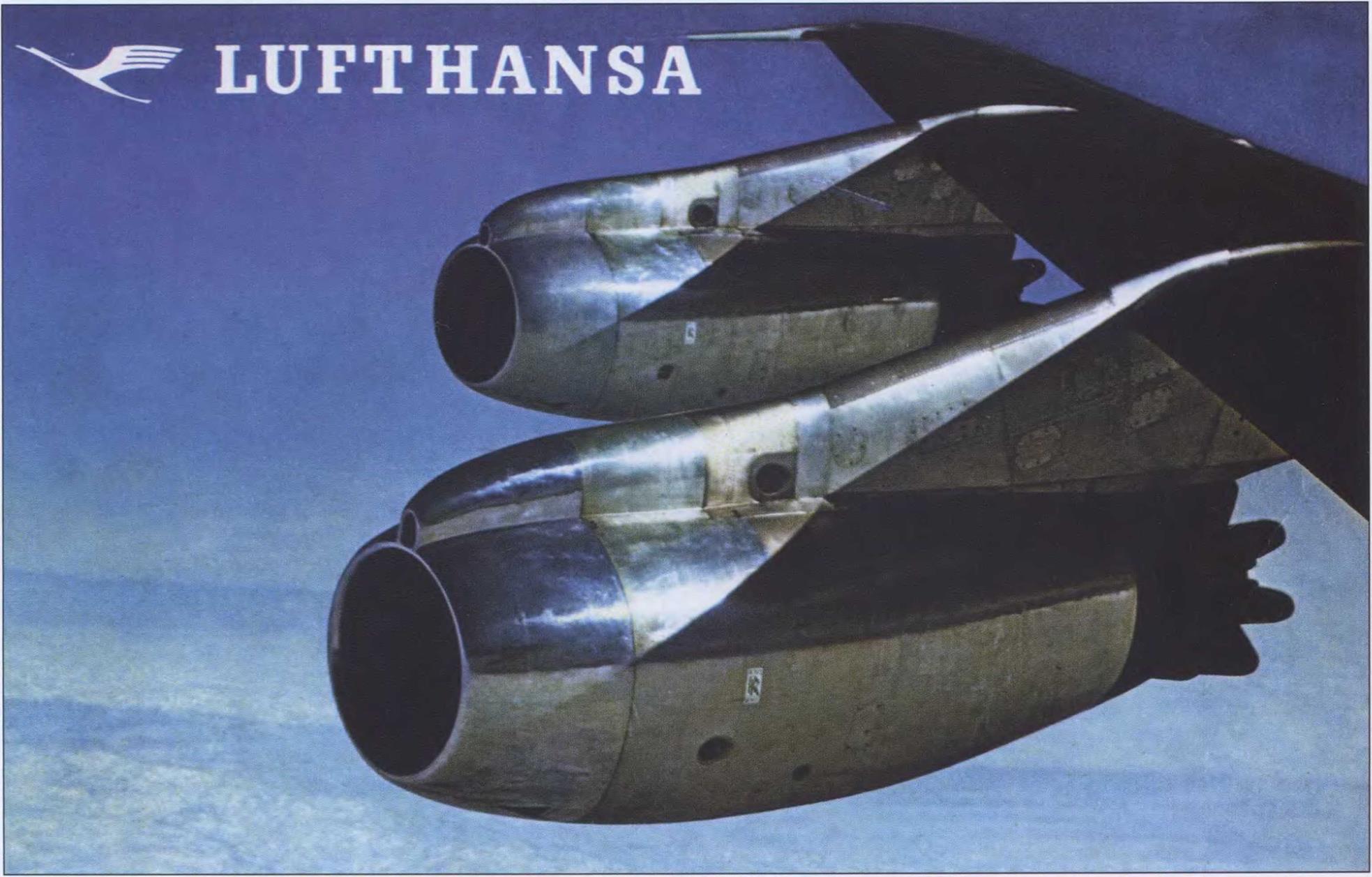

We, the authors, are honored to present these Ren Wicks images as contained in TWA’s original 1959 Boeing 707 promotional brochure. They capture, in every sense of the word, the spirit of wonderment that pervaded the public consciousness about this burgeoning era of jet – powered commercial flight. From spacious cabin interiors to detailed flight galleys, to modern stylish lavatory decor—it’s all here. Representing the Boeing 707 Intercontinental model is an original 1960 Lufthansa brochure for its Rolls-Royce Conway-powered 707-420, the first airliner in history to feature a wooden beer stein onboard for the First Class Senator Service.

Augmenting these beautiful brochures is a series of 16 photographs of 707s in various models and color schemes from, with few exceptions, the very first years of 707 service. You will note that this book is dedicated to the memory of Terry Waddington, a star member of the marketing and sales team for McDonnell Douglas in Long Beach, California. Terry was also a slide collector who amassed a sizeable archive of 35mm imagery from around the world that was second to none. By special arrangement, the Waddington estate has made these slides available to us, and we present them here in Terry’s honor. We hope that through these historic original images, the Boeing 707 will once again come alive.

Appearing more like the passenger cabin aboard a much larger aircraft, this 707 forward lounge featured all the amenities of luxury and elegance aloft. Note the relative scale of the people compared to the airplane.

Just as a full-width mirror enhances the overall size of any room, this 707 lavatory looks absolutely spacious with ample shelf space and ultra-modern appointments and fixtures. A new jet airliner had to be impressive.

In a day and age when inflight service was the core of any airline’s existence, a well-equipped and fully stocked galley was as essential to the overall passenger experience as a high-tech cockpit was to the pilots.

|

Lufthansa’s new Boeing 707-420 rolls out of the company’s Renton facility on a typically rainy day in Seattle. This larger "Intercontinental" version of the 707 carried more passengers and flew farther than the 100-series.

|

|

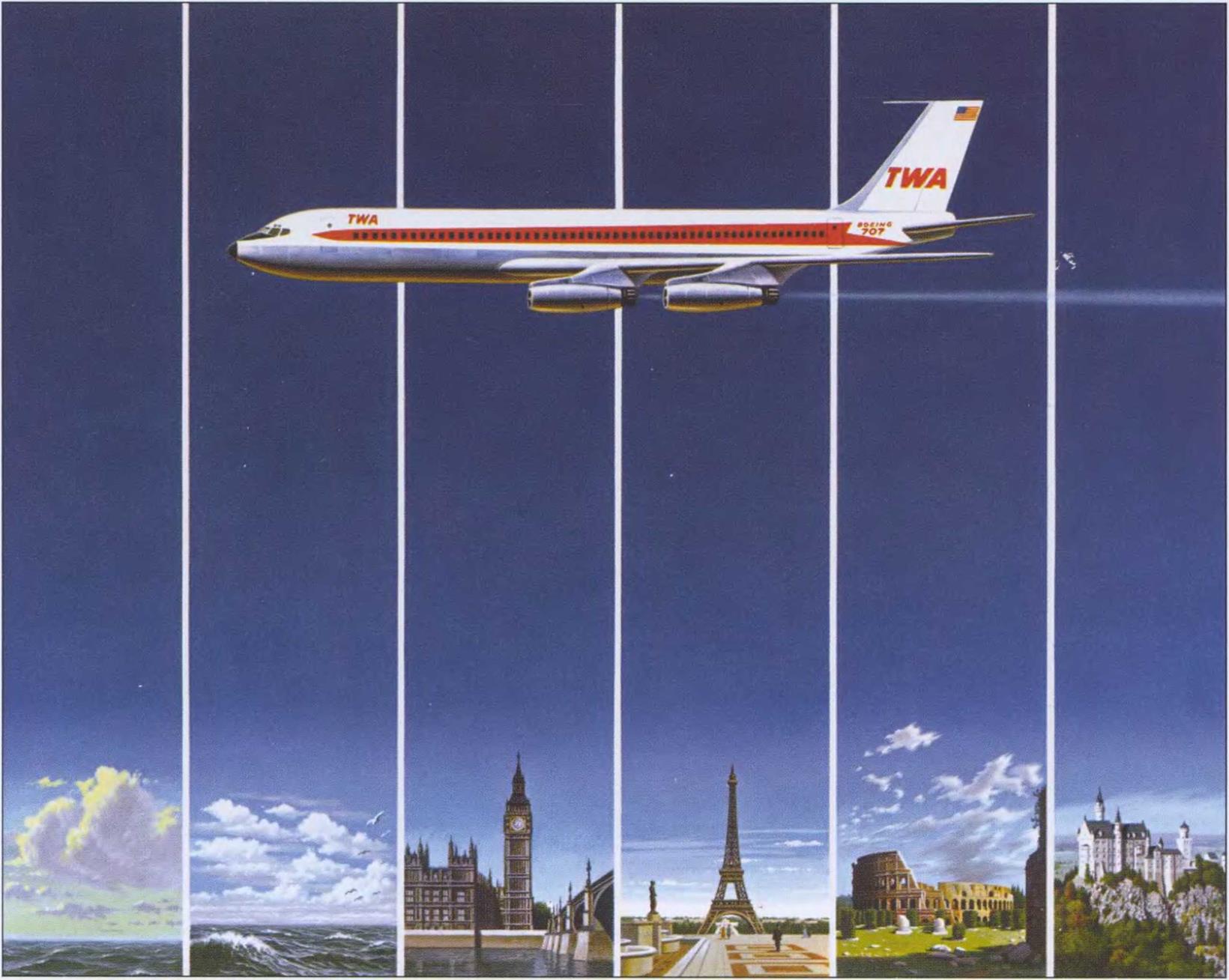

Replacing the passenger’s view of oil-splattered radial engine cowlings was this impressive vista of sleek turbojet engine nacelles connected by slim pylons to a swept wing. The wingtip probe was a radio antenna.

|

In today’s world of $8 snack boxes, it may be difficult to fathom the thought of Lufthansa’s Senator Service, and sumptuous meals being served at your seat. Inflight dining had all the amenities of five-star international cuisine.

Supplying delicious food and all the accoutrements was the responsibility of an Airline’s Chief Chef. Although perhaps not onboard every flight, this enthusiastic cook looks every bit the part of TV chefs today.

m-m –

m-m –

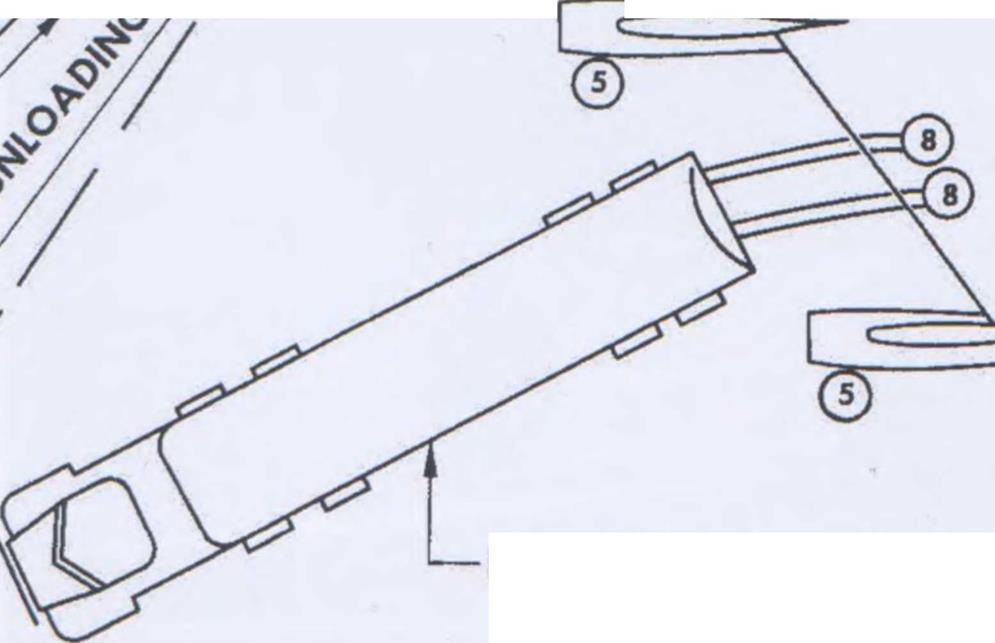

Continental’s "Golden Jet" service on the 707 literally set the standard for competition within the airline industry early in the Jet Age. Special custom-built motorized boarding ramps (lower right) were used to protect passengers from the elements before the advent of enclosed jetways. Shown here at Chicago’s O’Hare, 707 Golden Jets brought jet transportation to other Midwestern cities not served by jetliners at the time. (Jon Proctor)

Pan American and Trans World Airlines were the largest Boeing 707 operators. Arriving at the International Arrivals Building (IAB) at New York’s then-ldlewild Airportf Pan Am 707-321 carried the name Jet Clipper Splendid. Note the array of aircraft visible in the background, from an Air France 707-320 at the gate to a turboprop National Lockheed Electra, Pan Am DC-8, and even a classic American Douglas DC-6B taxiing in the distance. (Jon Proctor)

Braniff ad execs liked to refer to their "Big Jets/’ as reflected by the large red "-227" seen on this aircraft’s aft fuselage. Combining the domestic body and more powerful engines from the 300-series, the -227 was unique to Braniff. The aircraft could fly faster than its 707-100 counterparts, and was able to carry heavier payloads out of "hot and high" airports such as Mexico City as well. This "Big Jet" is shown at Dallas’ Love Field. (Robert Proctor)

Initially operating Rolls-Royce Conway-powered 707s, BOAC later acquired Pratt & Whitney turbofan models. Featuring the stylish new "speedbird" logo seen in metallic gold on the tail, the airline adopted a slightly modified livery from the midnight blue-and-ochre delivery color scheme seen on page 126. Note BOAC logos on the forward engine pylons, a carry-over from the airline’s Comet 4 "slipper" fuel tank markings. (Jon Proctor Collection)

Air India also opted for Rolls-Royce Conway engines on its initial fleet of Boeing 707 Intercontinentals. Named Gauri Shankar, VT-DJJ is seen here in a handsome modified 707 color scheme being prepared for departure at Zurich, Switzerland. Although technically a turbojet, the Rolls-Royce Conway was known as a "bypass" engine, offering slightly higher thrust. It served as a precursor to the true turbofan engine. (Jon Proctor Collection)

|

Sabena Belgian World Airlines became an international 707 operator offering transatlantic service beginning in January 1960. This airplane’s handsome color scheme, seen here at Orly Airport in Paris, was adapted directly from the design used on the airline’s Douglas DC-7C intercontinental propliners before delivery of its 707s. The 707-320 carried 165 passengers and had a cruising speed of 600 mph. (Jon Proctor Collection)

|

El Al operated a weekly New York-Tel Aviv "nonstop" with its Rolls-Royce-powered Intercontinental 707s, but most trips stopped both ways at London’s Heathrow Airport, where this picture was taken. Wearing a revised color scheme designed in 1971 for the airline’s new Boeing 747 jumbo jet, this 707 serves as a nice example of how the airplane’s classic lines look good even in more modern colors. (Jon Proctor Collection)

Г1ШШ

South African Airways (Suid-Afrikaanse Lugdiens), was known for luxurious in-flight services on its three 707-344s. ZS-CKC is seen here on push-back at London-Heathrow. Like other carriers, SAA later took advantage of Pratt & Whitney turbofan-powered Boeings, which were better suited to the airline’s high-altitude destinations. The 707- 300B series offered maximum gross takeoff weights of 330,000 pounds. (Jon Proctor Collection)

South African Airways (Suid-Afrikaanse Lugdiens), was known for luxurious in-flight services on its three 707-344s. ZS-CKC is seen here on push-back at London-Heathrow. Like other carriers, SAA later took advantage of Pratt & Whitney turbofan-powered Boeings, which were better suited to the airline’s high-altitude destinations. The 707- 300B series offered maximum gross takeoff weights of 330,000 pounds. (Jon Proctor Collection)

An original DC-8 operator, Eastern acquired 720s for short – to medium-range routes, chiefly on the U. S. East Coast and to Puerto Rico. Using both passenger boarding doors, N8712E awaits customers at West Palm Beach. The aircraft’s attractive "arrowhead" motif was Eastern’s ninth variation of its original jet color scheme designed for the DC-8 in 1960, and was applied to many of Eastern’s older propliners as well. (Jon Proctor)

|

After leasing two 707s to enter the Jet Age, Western concentrated on turbo-fan-powered 720s, which were ideally suited for its route structure on the West Coast, across the Mountain region, and to Mexico. An updated "Indian Head" livery debuted on the type. N93152 is seen here being pushed back from the gate at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. Note Beechcraft "commuter" at lower right. (Jon Proctor Collection)

|

5AUDI ARABIAN AIRLINES

5AUDI ARABIAN AIRLINES

In December 1961, Saudi Arabian flag carrier Saudia acquired two 720Bs originally built for Ethiopian Airlines, for use on flights between the Kingdom and destinations in Europe and North Africa. Showing the airline’s dramatic change to jets, 720s replaced Convair 340 twins and DC-6As. The second 720 aircraft is seen here resting between flights at London-Heathrow, wearing its second distinctive dark green-and-gold livery. (Jon Proctor)

Beginning 707-328 service in January 1960, Air France added Pratt & Whitney turbofan models as it built up a large fleet of the Boeing jets. Chateau de Dampierre is shown here arriving at Boston’s Logan International Airport, and was later retired and placed on permanent display at Le Bourget Airport in Paris. Fittingly, LeBourget was the destination of Pan American’s inaugural 707 service in October 1958. (Jon Proctor Collection)

One of the first charter airlines to acquire newly manufactured jetliners, World Airways used convertible 707-373Cs worldwide, including civilian flights, military "MAC" charter, and cargo services. Shown in World’s attractive red- and-white livery, a passenger flight arrives at Manchester, England. The 707-300-series’ 143-foot wingspan can be seen here. Passenger capacity for MAC flights could reach 165. (Jon Proctor Collection)

Dwight D. Eisenhower was the first U. S. president to fly in a jet-powered aircraft, using a Boeing 707-120 operated by the Military Air Transport Service (MATS). This rare and historic photograph shows the turbofan-powered VC-137C (707-320B) Air Force One as it landed at San Diego on June 6, 1963. President John F. Kennedy was aboard the aircraft that day, barely five months before his tragic assassination. (Jon Proctor)

r І///1 * f-‘sl /7111

r І///1 * f-‘sl /7111

mMillWrtiWtWiWiItIa] й [аРИ

Colombia’s national carrier Avianca received its first Boeing jet, a 720B, in November 1961, and acquired several new and second-hand examples before upgrading to intercontinental 707-359Bs, including HK-1402, seen here at the International Arrivals Building at New York’s JFK in May 1968. It is interesting to note the use of mobile boarding stairs at a time when most Jet Age airports had more modern jetways. (Jon Proctor Collection)

POrnUGUEbE^ мMi митім

|

|ЛИШ

|

* .

|

|

|

|

|

|

•

|

|

|

|

|

|

■■ шт

|

— гг – ■ ‘«І – •: – >

|

|

|

|

‘ Ш® ЩШ -$Шк Ш

|

|

|

|

|

|

‘ ;i;W

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Air Portugal was a relatively late customer for the 707, beginning service with the type in early 1966. CS-TBG, named Fernao de Magalhes, was one of the last commercial 707s to roll off the assembly line, and was delivered to TAP in March 1970. A total of 1,010 707s were built for the world’s airlines and the military from 1958 to 1991. Military 707s flew for the U. S. Air Force, the Navy, NATO, and several foreign air arms. (Jon Proctor Collection)

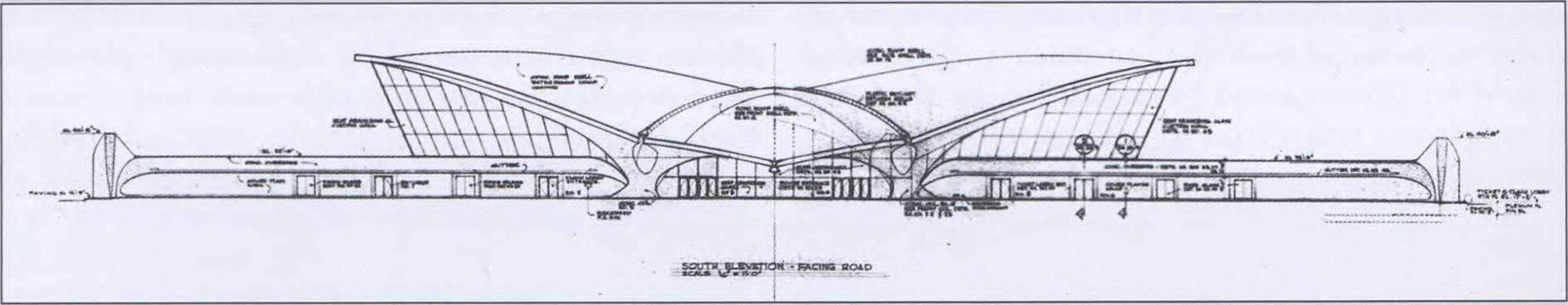

With air travel being such an entirely different experience today, we will simply have to remember the glory days of DynaFan-powered StarStream 707s pulling up to the jetways, with passengers dining in the Paris Cafe and celebrities having one last drink at the Lisbon Lounge before jetting off to Europe, Africa, or the Far East. Now, as an integral part of JetBlue’s stunning new JFK terminal, the former TWA “Terminal of Tomorrow” still stands silently in solemn tribute to the dawning of the Jet Age.

With air travel being such an entirely different experience today, we will simply have to remember the glory days of DynaFan-powered StarStream 707s pulling up to the jetways, with passengers dining in the Paris Cafe and celebrities having one last drink at the Lisbon Lounge before jetting off to Europe, Africa, or the Far East. Now, as an integral part of JetBlue’s stunning new JFK terminal, the former TWA “Terminal of Tomorrow” still stands silently in solemn tribute to the dawning of the Jet Age.

exhaust velocity of nearly 30 mph at a distance of more than 100 feet behind the airplane.

exhaust velocity of nearly 30 mph at a distance of more than 100 feet behind the airplane.

Commercial Avation’s Transition to the Jet Age 1952-1962

Commercial Avation’s Transition to the Jet Age 1952-1962

![THE TERMINAL OF TOMORROW Подпись: Unlike on the BOAC Stratocruisers and DC-7Cs that preceded it, the Comet 4's interior was virtually noise and vibration free. According to BOAC ad copy in 1958, the Comet 4 offered passengers a "fusion of speed and rock-like stability [yielding] an impression of being suspended comfortably in space." Interior configuration shown here featured 16 first-class sleeper-seats in the forward cabin and 43 tourist seats aft. (Craig Kodera Collection)](/img/1246/image184_0.gif)

The work of one of the true masters of modern American^illustration, this

The work of one of the true masters of modern American^illustration, this

m-m –

m-m –

South African Airways (Suid-Afrikaanse Lugdiens), was known for luxurious in-flight services on its three 707-344s. ZS-CKC is seen here on push-back at London-Heathrow. Like other carriers, SAA later took advantage of Pratt & Whitney turbofan-powered Boeings, which were better suited to the airline’s high-altitude destinations. The 707- 300B series offered maximum gross takeoff weights of 330,000 pounds. (Jon Proctor Collection)

South African Airways (Suid-Afrikaanse Lugdiens), was known for luxurious in-flight services on its three 707-344s. ZS-CKC is seen here on push-back at London-Heathrow. Like other carriers, SAA later took advantage of Pratt & Whitney turbofan-powered Boeings, which were better suited to the airline’s high-altitude destinations. The 707- 300B series offered maximum gross takeoff weights of 330,000 pounds. (Jon Proctor Collection)

5AUDI ARABIAN AIRLINES

5AUDI ARABIAN AIRLINES

r І///1 * f-‘sl /7111

r І///1 * f-‘sl /7111

A cocktail lounge located at the front of the 749A Constellation passenger cabin provided a casual atmosphere for passengers awaiting dinner, or makeup of their sleeping berths, on TWA’s nonstop Ambassador Service from New York to London.

A cocktail lounge located at the front of the 749A Constellation passenger cabin provided a casual atmosphere for passengers awaiting dinner, or makeup of their sleeping berths, on TWA’s nonstop Ambassador Service from New York to London.

This extra power was used to lift an additional 1,100 gallons of fuel, which boosted the range of the Electra beyond its originally planned 2,500 miles, all the way to 3,460. The В designation was an unofficial tag used internally by Lockheed to denote the Electra with navigator stations and extra lavatories destined for use by the international airlines.

This extra power was used to lift an additional 1,100 gallons of fuel, which boosted the range of the Electra beyond its originally planned 2,500 miles, all the way to 3,460. The В designation was an unofficial tag used internally by Lockheed to denote the Electra with navigator stations and extra lavatories destined for use by the international airlines.

Unlike Pan American, TWA held off overseas jet service until its intercontinental 707-300s arrived, eliminating the need for fuel stops on flights to Europe. An example is seen at New York-ldlewild’s International Arrivals Building (IAB), wearing the twin- globe logo scheme adopted two years after entering service. (Jon Proctor)

Unlike Pan American, TWA held off overseas jet service until its intercontinental 707-300s arrived, eliminating the need for fuel stops on flights to Europe. An example is seen at New York-ldlewild’s International Arrivals Building (IAB), wearing the twin- globe logo scheme adopted two years after entering service. (Jon Proctor)

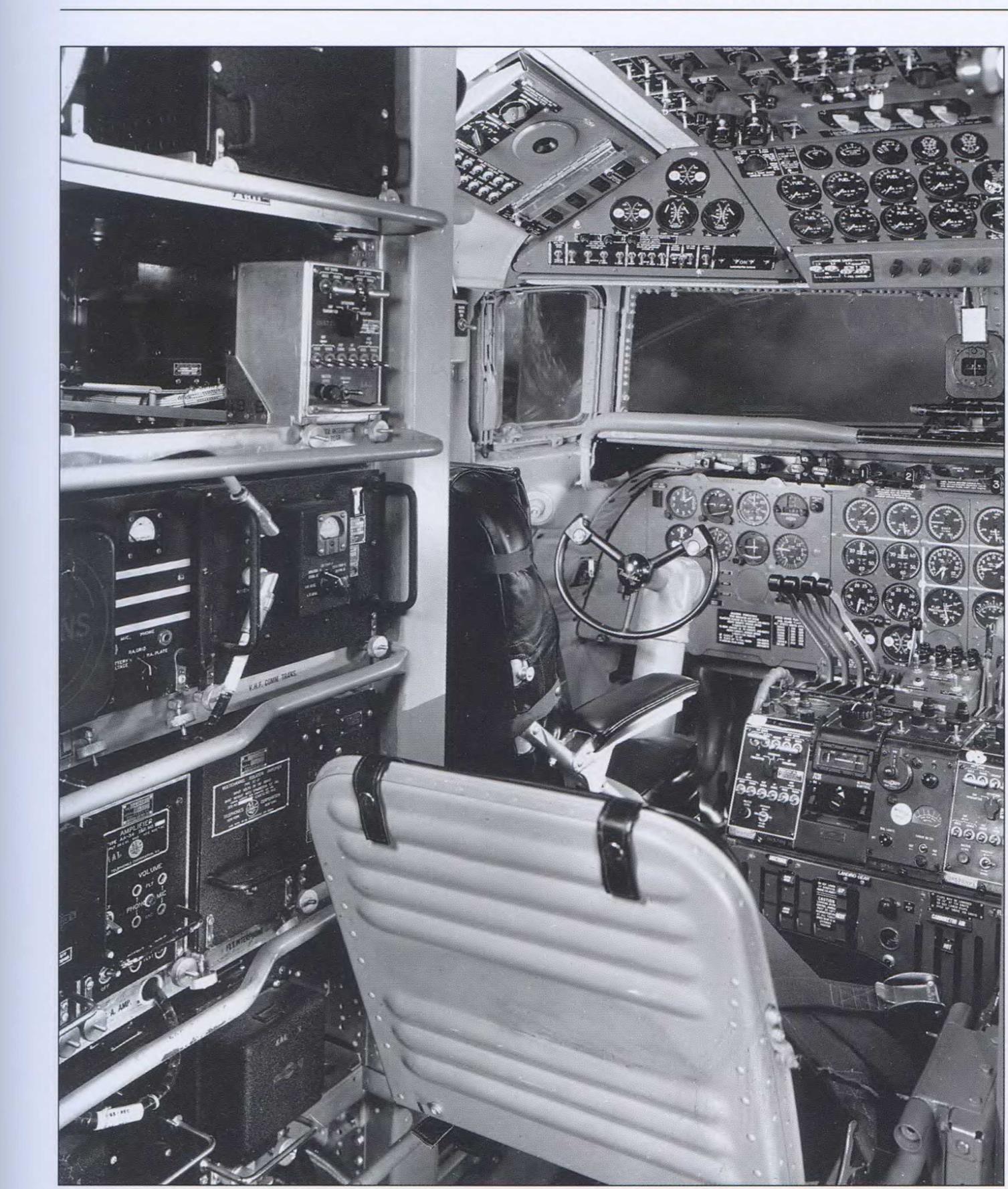

Cockpit of the DC-7 shows a well-laid-out instrument panel and control pedestal with the throttles, radio consoles, and trim wheel readily at hand. Flight Engineer’s seat is facing forward in this photo giving him access to the control pedestal and the overhead panel controlling the aircraft’s many onboard systems. Radio rack at left provided easy access for avionics maintenance personnel who may have had to change an entire radio unit or repair one of the many vacuum tubes contained therein. (Mike Machat Collection)

Cockpit of the DC-7 shows a well-laid-out instrument panel and control pedestal with the throttles, radio consoles, and trim wheel readily at hand. Flight Engineer’s seat is facing forward in this photo giving him access to the control pedestal and the overhead panel controlling the aircraft’s many onboard systems. Radio rack at left provided easy access for avionics maintenance personnel who may have had to change an entire radio unit or repair one of the many vacuum tubes contained therein. (Mike Machat Collection)

This work by famed artist Ren Wicks depicts the dome lighting of TWA’s 707s, designed to look like portholes in the aircraft ceiling. At night, pinholes of light against a dark background gave the impression of a night sky filled with a galaxy of stars. (TWA/Jon Proctor Collection)

This work by famed artist Ren Wicks depicts the dome lighting of TWA’s 707s, designed to look like portholes in the aircraft ceiling. At night, pinholes of light against a dark background gave the impression of a night sky filled with a galaxy of stars. (TWA/Jon Proctor Collection)

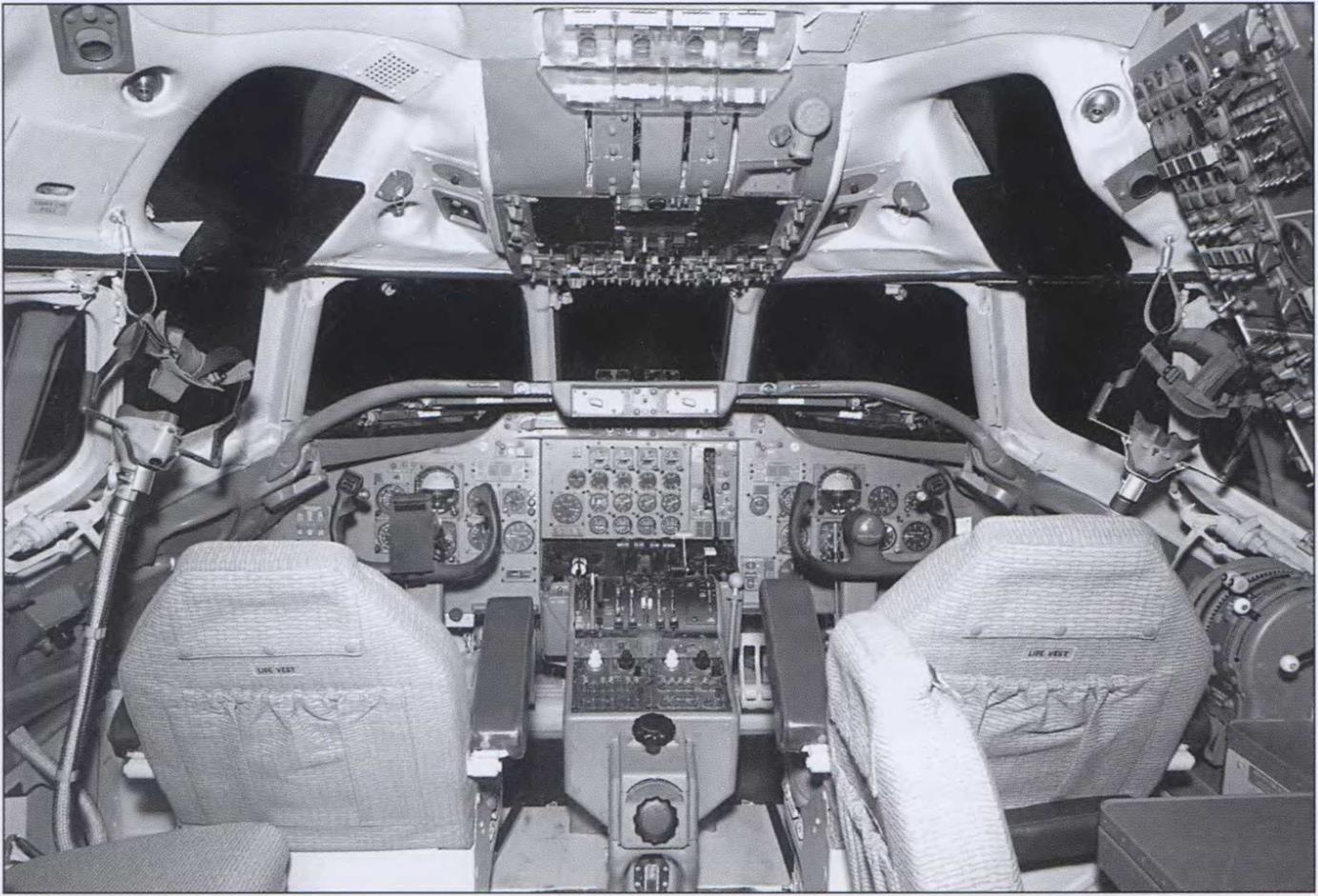

The DC-8’s cockpit was much roomier and offered much greater outward visibility than that of its piston-powered predecessors. Flight Engineer’s station is visible to the right with an observer’s jump seat at extreme left. Note move – able sunshades mounted on a circular track to ensure placement anywhere they were needed, a unique Douglas feature. Emergency quick – donning oxygen masks seen hanging next to each seat were a new addition for the flight crew. (Mike Machat Collection)

The DC-8’s cockpit was much roomier and offered much greater outward visibility than that of its piston-powered predecessors. Flight Engineer’s station is visible to the right with an observer’s jump seat at extreme left. Note move – able sunshades mounted on a circular track to ensure placement anywhere they were needed, a unique Douglas feature. Emergency quick – donning oxygen masks seen hanging next to each seat were a new addition for the flight crew. (Mike Machat Collection)