Making a Difference

Musgrave’s story made a difference. It helped to bring what it described into being. If we want to pick through the entrails and ask how it achieved this, we could use various theoretical vocabularies for talking of interference effects. We might talk of intertextuality— for here, certainly, we have one form of talking that interacted with others, those, for instance, of the industrialists, to produce the effect of reordering the aircraft industry. Again, we might talk, like the actor – network theorists or Donna Haraway, of the performance of materio – semiotic relations,7 and then we might remind ourselves that narratives work themselves through a range of materials. So we’d note that it certainly wasn’t the honeyed power of Musgrave’s voice that performed the industrialists into submission, that made the difference by reordering the distributions of British industry. He might just as well have croaked like a frog, and the outcome would still, might still, have been the same.

So be it. Such is the character of interference: it comes in many forms and operates in many ways. It may be told of too, performed, in many ways. But what about my arborescent narrative? What about the stories of the technoscience student? Or those of Gardner, the company historian? How are they working? And how do they intersect?

We agreed pro tem to lodge these narratives in the ‘‘report’’ pigeon hole, the place where we put ‘‘the government has fallen.’’ This place is inhabited by constatives in the realm of epistemology. The reason is that, notwithstanding all the strictures about subjects and objects that make themselves together, these stories don’t seem to be making any difference. They aren’t acting upon, or better, within whatever they report.

But this distinction doesn’t really work, does it?

‘‘Was O. R.343 a Valid Concept?’’

180 Arborescences ‘‘Should a Short-Step Aircraft have been Produced?’’

‘‘Was a Sophisticated TSR Aircraft Necessary?’’

‘‘Was the Cancellation Justified?’’

‘‘Was a TSR-2 Aircraft Necessary in 1965?’’

‘‘Was the Aircraft Industry too Large?’’

‘‘Had TSR-2 to be Cancelled to Further European Airspace Collaboration?’’

These are chapter and section headings taken from a small book called Crisis in Procurement: A Case Study of the TSR-2, which I’ve already cited several times (Williams, Gregory, and Simpson 1969).

This publication appeared in 1969, four years after the cancellation, but the headings give the game away. They tell us that it is not simply a report. It is rather a document that’s trying to answer policy questions.

Some more citations from the same source:

By quantifying the quantifiable, therefore, the 1965 TSR-2 decision can be shown to be correct, though the gains from its cancellation were so small that a slight alteration of estimates could easily have produced a contrary argument. However, when the unquantifiable elements are added, the issue becomes an even more open one, so much so that it is difficult to arrive at a clear – cut answer by rational analysis. . . .

However, had the normal accounting conventions been altered in the way that has been suggested, and greater account taken of the increased reliability and availability of TSR-2 as a weapons system, it would have been valid to argue that the TSR-2 ought not to have been cancelled for the F111K. It is interesting to speculate, however, how far these detailed arguments were presented to the decision-makers concerned in terms of a dispassionate analysis of the alternative assumptions involved, and the related probable outcomes. If they were not, no truly informed decision was possible, and the decision taken would automatically be a bad one in decision-making terms. (Williams, Gregory, and Simpson 1969, 66)

So this is another recommendation about the distributions proper to centered decision making. Which is another way of saying that it is also a policy report: ‘‘In the preceding chapters the difficulties which Arborescences 181

beset the TSR-2 project have been analysed. . . . An attempt will now be made… to relate these difficulties to the production of future British weapons systems’’ (Williams, Gregory, and Simpson 1969,67). It is a policy report that, no doubt, aims to make a difference. It is an ‘‘I do,’’ or at the very least a version of ‘‘I love you’’ or ‘‘the government will fall.’’ So it is all about performativity. It is about making. Like Musgrave, it’s about uncertain performativity, a description of how it was, how it is, how it should be, how it might be. It’s about the performative uncertainties that arise when (as is almost always the case) the character of the interferences between different stories is uncertain.

Williams and his friends are thus different from Musgrave. We want to say, don’t we, that Musgrave was ‘‘more deeply involved,’’ more of a participant than Williams and Co.? On the other hand, we’re also learning, or so it appears, that overlap and participation is a gradation. Or better, we’re learning that whether or not the author of a narrative—or perhaps better a narrative itself—participates in what is being narrated depends on how the line is drawn between inside and outside, which is perhaps a way of talking about how the overlaps between performances are built and rebuilt.8 We might want to say, for instance, that Williams and his friends were outsiders to the TSR2 project, but not to the ‘‘defense policy community’’—ex – cept, of course, we’d also need to add that such a distinction is itself performed, an effect. It is a patterning of narrative distributions that makes similarity and difference in the slippery place between ‘‘I do’’ and ‘‘I love you,’’ between ‘‘the government will. . .’’ and ‘‘the government has…,’’ between the descriptions of simple epistemology and the world making of ontology. Which is, no doubt, where we all are, where all stories are to be found, multiply distributed in the fractional interferences between telling and doing.

So there are four narratives in play: the arborescent story of the social shaping of technology with which I opened this chapter; Charles Gardner’s narrative, the story of the British Aircraft Corporation as written by the historian; Cyril Musgrave’s story, the account offered by, or on behalf of, the senior civil servant; and there are the recommendations of the policy analysts, Williams and his friends. At which point the density of these intersections begins to become some – 182 Arborescences what overwhelming. But that is how it is.

Intersections

The following citations come respectively from my summary story,

Gardner’s story about Musgrave, and Williams’s account written with his friends.

So he issued a government policy statement, a ‘‘White Paper,’’ in which he boldly announced that the government would no longer develop most forms of military aircraft.

The Government hoped for eventual rationalisation and amalgamations. . . . How the industry so grouped itself was its affair, but group itself it must.

By quantifying the quantifiable, therefore, the 1965 TSR-2 decision can be shown to be correct.

We’ve established some of the differences between these. ‘‘Plain history,” participation, policy, certainly they perform differences, and if they are performative then they perform different TSR2 projects.

Multiplicities. But then the question we’ve been wrestling with all along recurs: Do they not also interact together in ways that tend to create a single object, a single project?

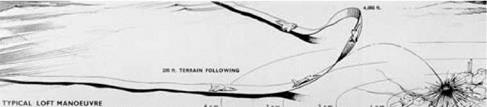

The question is rhetorical. The answer I want is that they indeed intersect. They intersect in terms of specificities. They coordinate themselves by talking of ‘‘the same’’ events, or ‘‘the same’’ project, but as they frame and perform these specificities they also make ‘‘the same’’ conditions of ontological possibility-singular conditions. I said that my narrative is arborescent in character, that it is like a bonsai tree, existing in and making a literal and metaphorical Euclidean space-time box. But if it is a little version of a large tree, an arbo – rescence, then it also makes roots and branches. It performs places where different lines come together, junctions that are more or less important, closer to or more distant from the trunk. It makes bifurcations and confluences to create this developing project-plant.

In the way that I have told the story, I have attended most of all to the place where the decision was made to build the aircraft and to build it in a particular form. To a smaller extent I have also described the decision to cancel. The tree makes, most of all, a project beginning and a project end. The story that I told organized itself around these:

the joining of the twigs into branches achieved their status, their sa – Arborescences 183

|

184 Arborescences |

lience, their hierarchical import, in relation to the beginning and the end. The smaller narratives, however, are also built to the same pattern. It is possible to be more precise. They are all about the decision points that appeared in my narrative, important bifurcations. They all perform ‘‘aspects’’ of those decision points. They tell us, ‘‘in more detail’’ about places where particular twigs came together to form branches, or particular branches came together to form the trunk. They explain why the decisions took the form that they did, why the tree grew in this way rather than that. So no doubt it is possible to read them in other ways, but within the project-relevant, bonsai, space-time box of my arborescent narrative, these smaller narratives perform the same pattern. It is just that they do so at a higher level of magnification. Increase the magnification and what do we get? The same bifurcations at greater length. Or an expanding pattern of further bifurcations and sub-bifurcations that go toward making the larger branching point. Branchings and more branchings—the interferences between the different narratives are treelike in form. They make a stable pattern of interference as they overlap because they are self-similar. Branches go on appearing as magnification increases: in their structure they are scale independent.9 So time and space are arborescent effects. But so, too, is scale. Indeed, space, time, and scale are made together. To make a spacetime box is to imagine the possibility of looking at the contents of the box ‘‘as a whole.’’ As singular. In this way the notion of ‘‘the whole’’ achieves some sort of possibility. But to make wholes is also to make parts. It is to allow—indeed to call for—magnification. Better, it is to imagine magnification as a possibility that gives it some sort of sense. This is what makes it possible to say that Cyril Musgrave’s narrative is a ‘‘detail’’ of the ‘‘larger’’ narrative with which I started this chapter. This would make it possible to locate Musgrave’s narrative, from the point of view of ‘‘the whole story,’’ in a footnote. To put it in a black box. Like the subsections of the brochure in the table of contents, it makes it possible to say that his story is a ‘‘detail.’’ But which also, and in the same movement, makes performative the distributions of size. Including the performance of my ‘‘larger’’ narrative as, indeed, ‘‘the story as a whole.’’ Arborescence is a hierarchical structure, a system of points and |

positions, an axis—I am simply using Claire Parnet’s metaphors— that domesticates particulars by locating them, without potential limit, in a salient and scaled space-time grid. It is a location that performs Haraway’s god-eye trick, which makes a four-dimensional view from nowhere. It defines and performs the conditions of possibility for particular stories. And it is this potential to locate that shapes the nature of interferences between specifics. It also defines two great questions: the epistemological question, which asks whether this story is real, and the occluded ontological question, which asks about performativity as a function of interference, deferral, and the structures of possibility.

The tree is one of the great metaphors for disciplining interferences. ‘‘The whole world demands roots.’’ I take it, however, that there are other relations and overlaps. That it is possible to perform other interferences.