THE SPACESHIP TO LAND ON THE MOON: THE LUNIY KORABL, LK

The descent of the Soviet lunar lander, called the LK (Luniy Korabl), to the lunar surface would be a steep one. The final lunar orbit would be 16 km by 85 km, the same as the final orbit of the later Ye-8-5 lunar sample return missions. Block D would fire at the 16 km perilune, bringing the LK to between 2 km altitude (maximum) and 500 m (minimum), ideally 1,500 m. If all went well, the LK pilot would set the LK down about 25 sec thereafter, but not more than a minute later. The LK would descend to 110 m, when it would hover: then the cosmonaut would take over for the landing. The instructors told the cosmonauts that at 110 m, they had three seconds to select a landing site, or return to orbit (‘as if returning at this stage was an option’, snorted Leonov). The standing cosmonaut, watching through his large, forward-looking window, would guide the LK lander with a control stick for attitude and rate of descent.

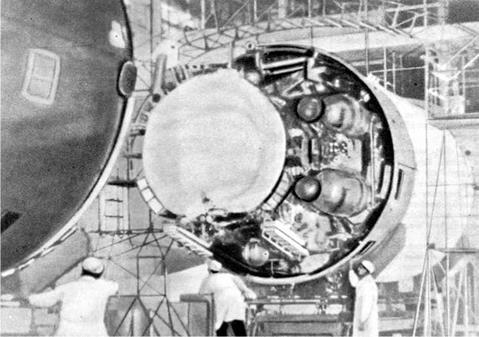

The engine, called block E, was designed by the Mikhail Yangel OKB-586 in Dnepropetrovsk. It was a well-equipped propulsion set. The LK module had:

• One 11D411 RD-858 main engine weighing 53 kg with a single nozzle with a specific impulse of 315 sec, chamber pressure of 80 atmospheres and duration of 470 sec.

• A 11D412 RD-859 57 kg backup engine with two nozzles.

• Four vernier engines.

• Two 40 kg thrusters for yaw.

• Two 40 kg thrusters for pitch.

• Four 10 kg thrusters for roll.

The descent and take-off engine was a throttlable, single-nozzle, 2.5-tonne rocket burning nitrogen tetroxide and UDMH. It could be throttled between 860 kg thrust and 2,000 kg. The engine held 1.58 tonnes of nitric acid and 810 kg of UDMH. The engine had four verniers to maintain stability. For attitude control during the nerve – wracking descent to the moon, eight low-thrust engines designed by the Stepanov Aviation Bureau fed off a common 100 kg propellant reserve. The system was both safe – it ran off two independent circuits – and sensitive, for thrust impulses could last as little as nine milliseconds. To land the LK, the cosmonaut had a computer-assisted set of controls, the first carried on a Soviet manned spacecraft. The S-330 computer was a sophisticated digital machine, linking the cosmonaut’s commands to the lander’s gyroscopes, gyrostabilized platform and radio locator, with three independent channels working in parallel [18]. Four upward-firing solid rockets would ignite on landing, to press the LK onto the surface. The lander was designed to take a slope of 20°.

The LK was different from the Apollo lunar module (LM) in a number of important respects. These were a function of the much poorer lifting power of the N-1 rocket. First, it was much smaller, being only 5.5 m tall and weighing 5 tonnes (the LM was, by contrast, 7 m tall and weighed 16 tonnes). It had room for only one cosmonaut standing and the lower stage would have no room for the extensive range of scientific instruments carried by Apollo. Second, the LK had a single 2,050 kg thrust main engine which was used for both descent and take-off (Apollo’s LM had a descent motor and a separate one for the small upper stage). Like the LM, the LK would use the descent stage as a take-off frame. The LK was designed for independent flight of 72 hours and up to 48 hours on the lunar surface. The LK was a minimalist approach to a lunar landing. Although the method of landing on and take-off from the moon was broadly similar, there were some important differences:

• The American LM descent engine carried out the entire 12 min descent from PDI (powered descent initiation) to touchdown. By contrast, block D provided most of the thrust of the descent of the Soviet LK. Block D was dropped around 1,500 m above the surface and the LK’s descent stage took over for the final part.

• The American LM had two motors, one for descent and one for ascent. By contrast, the Russian LK had just one motor, which was used for descent and ascent.

What would the LOK-LK mission have been like? It would begin with the launching, from Baikonour Cosmodrome, of two cosmonauts on the N-1 rocket. The three stages

|

The LK |

of the N-1 rocket would burn until the lunar stack was safely in an Earth orbit of 51.6°, 200 km. At the end of the first parking orbit, the fourth stage, block G, would fire for translunar injection. This block would then separate.

Unlike Apollo, there would be no transposition, docking and ejection of the lunar module. This would remain behind the command ship, the LOK, as they headed moonward. On the way to the moon, the fifth stage, block D, would fire for a translunar correction. Three days into the mission, block D would fire the stack into lunar orbit. The descent from lunar orbit would again be different from Apollo. First, a lone cosmonaut would enter the lunar module, the LK. Because there was no internal hatch, the cosmonaut would exit the hatch and climb down the side of the LOK along a pole before entering the access hatch. This would take place against the backdrop of the moon’s surface below and the spectacle would be stunning. Once on board the LK, the cosmonaut would then separate his lunar module and block D from the LOK mother ship. Here would come a fresh difference. The powered descent

|

LK hatch |

|

LK inside |

|

LK ladder |

|

LK window |

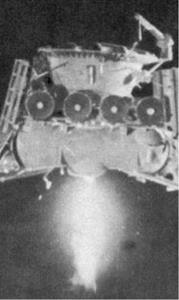

burn would be done by block D. It would be jettisoned a mere 1,500 m above the lunar surface, leaving the LK’s main engine to complete the descent to the lunar surface. This would be the same engine used for take-off.

Hover time was much tighter on the Russian LK than the American LM. The Russians had about a minute to find the landing site and put the spacecraft down. The pilot could, of course, use more than 1 min, since it was the same engine used for the ascent, but this would eat into the thrust required for ascent. The LM had a longer hover time, about 2 min. By the end of the 2 min, the LM would be out of fuel and the mission would have to abort. Below a certain altitude, the period of time for firing the ascent stage would be longer than the time taken to fall to the surface, so the LM would crash (this was called ‘dead man’s handle’). All but one of the Apollos were sufficiently well targeted not to present a problem. The most difficult landing was the first, Apollo 11, which landed with only 19 sec of fuel to spare. ‘Dead man’s handle’ did not operate on the LK, since the engine used for the ascent was already firing. Arguably, it was safer. The LK lunar lander, like Apollo, had four legs. The first Soviet moon landing would have been shorter than that of Apollo 11, without a sleep period.

Once on the surface, the sole cosmonaut would carry out a spacewalk. We do not know how long the first lunar stay was planned. A moonwalk duration of four hours has been suggested, so the surface stay time would have to be long enough to report back after landing, prepare for the moonwalk, carry it out, return and prepare for take-off and rendezvous.

After several hours on the surface, the cosmonaut would lift off from the moon in the upper stage of the LK, and conduct the type of rendezvous pattern tested by Cosmos 186-188, 212-3 and Soyuz 2-3 and 4-5 in which the LOK orbiter performed the active role. A backup two-nozzle engine was also available should the motor fail to light for the critical liftoff from the moon. On liftoff, the backup engine was actually fired simultaneously with the main engine, but turned off if the main engine lit up. The LK had five chemical batteries, three on the descent stage, two on the ascent. Cabin pressure was oxygen/nitrogen at 560 mm.

The return-to-Earth profile was quite like Apollo. The LK would lift off from the lunar surface, using the landing frame as a launching pad, like the American LM. The LK would link up with the LOK in lunar orbit and the cosmonaut would transfer to the LOK, though this would be by an external spacewalk (indeed, it would be his third that day). The LK would be dropped, and then the LOK would fire its main engine for trans-Earth injection. There would be a quiet coast Earthward, followed by a highspeed skip reentry over the Indian Ocean and a soft landing in Kazakhstan.

The LOK and L-1 spacecraft were expected to return to Earth in the standard recovery zone in Kazakhstan. Here, the Russians had extensive experience of the Air Force recovering spacecraft using helicopters, trucks, amphibious vehicles, adapted troop carriers and other vehicles able to traverse the flat steppeland. This experience had been built up during the Korabl Sputnik missions and the Vostok series and consolidated as the military photoreconnaissance Zenit series began making regular missions. The real problem was if the L-1 or LOK came down outside Soviet territory, either by choice or if the skip return failed and a ballistic path was followed instead. The Indian Ocean was the most likely maritime landing point. Here, in a decree issued on 21st December 1966, the Soviet Navy was made responsible for Indian Ocean recoveries. For Indian Ocean recoveries, ten naval and maritime research ships were involved, supplemented by three ship-borne helicopters, spread out at 300 km points along the ocean.

The LK

Weight 5,500 kg

Height 5.2 m

Diameter ascent stage 3 m

Span, descent stage 4.5 m

Habitable volume 4m3

Hover time 1 min

Weight, ascent stage 2,250 kg

Weight, descent stage 2,250 kg

Crew 1

Length of legs 6.3 m

Were Soviet computers up to the job? The Apollo 11 American lunar landing nearly aborted when the lunar module’s computer overloaded and flashed alarms in the LM cabin. The Apollo computers, though the most sophisticated of their day, would be regarded as laughably primitive nowadays. They were bulky, crude and had limited memory, but they played an important part in getting Apollo to the moon and back again. The popular assumption is that Soviet computers during the moon race lagged far behind American ones. This does not seem to be the case now. The Soviet Union had a long tradition in advanced mathematics and developed, in the late 1950s, its own silicon valley, partly assisted by two exfiltrated American electrical engineers, communists and friends of the Rosenbergs, Alfred Sarant and Joel Barr [19]. Taking on fresh names, Philip Staros and Josef Berg, they built up Special Design Bureau 2 (Spetsealnoye Konstruktorskoye Buro 2, SKB 2) which developed microcomputers for the Soviet aviation industry, military and space programmes. This included the Argon computer used on Zond. During the 1960s, SKB 2 developed a series of small, lightweight, sophisticated computers, from laptops to navigational devices to big calculating computers. Just because Soviet computers followed a different development path from the West did not mean that they were inferior, for they were not. The ability of the USSR to achieve automated rendezvous and docking in space (1967) went unmatched in the West until 1998 when the Japanese satellites Hikoboshi and Orihime met in orbit.