CLIMAX

With the flight of Zond 6, the Western press rediscovered the moon race. Time magazine ran a cover of an American and a Russian in a spacesuit elbowing one another out of the way as each raced moonbound. Newspapers printed cutaway drawings of ‘The Zond plan’ and ‘The Apollo plan’. Apollo 8 astronauts Borman, Lovell and Anders were right in the middle of their pre-flight checks. Their Saturn V was already on the pad. In London, Independent Television prepared to go on air with special news features the moment Zond went up. Models and spacesuits decorated the studio. The American Navy even broke international convention to sail eavesdropping warships into the Black Sea to get close to the control centre in Yevpatoria. The Americans had Baikonour under daily surveillance by Corona spy satellites. The whole world was waiting…

The launch window at Baikonour opened on 7th December. No manned Russian launching took place, to the evident disappointment of the Western media. They were of course unaware of the many problems that had arisen on Zond 5 or the even more serious ones on Zond 6. The Russians were in no position to fly to the moon in December 1968.

We now know that there were intense debates within the management of the Soviet L-1 programme in November and that many options were considered. The records of the time, like the Kamanin diaries, are contradictory and even confusing at

|

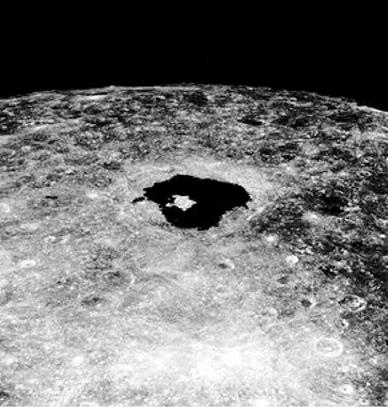

Zond over Crater Tsiolkovsky |

times, but they reflected the dilemmas faced by the programme leaders. On the one hand, they did not wish to be panicked into a premature response to what they considered to be the reckless American decision to send Apollo 8 to the moon; at the same time, they realized that, with their Zond experience, they were more prepared for a lunar journey than the Americans. The cosmonauts openly expressed their willingness to make the journey to the moon ahead of Apollo 8 – several report that they sent a letter to the Politburo – but as one government minister commented, ‘they would, wouldn’t they.’ It seems that Mishin’s natural caution prevailed. Years later, Mishin told interviewers that he had recommended to the state commission against such a mission: neither Zond nor Proton were yet safe. The state commission had agreed.

The success of Apollo 8 brought mixed feelings in the Russian camp. Leaders of the Soviet space programme were full of admiration for the American achievement, which they still regarded as a huge gamble. The Americans had gone one stage further than Zond, for Apollo 8 orbited the moon ten times. The Russians were full of regrets that they had not done it first and wondered whether they had made the best use of their time and resources since the first L-1 was launched in March 1967. The head of the cosmonaut squad, General Kamanin, made no attempt to downplay the significance of the American achievement. I had hoped one day to fly from Kazakhstan to Moscow on an airplane with our cosmonauts after they had circled the moon, he confided in his diary. Now he had the sinking feeling that such a pleasurable airplane flight would never happen.

The state commission overseeing the L-1 project met on 27th December and the safe return of Apollo 8, which took place that day, was very much in their minds. They set dates for the next L-1 launches at almost monthly intervals in early 1969, starting on 20th January 1969. Some asked What is the point?, a moot question granted that such a mission would now achieve less than Apollo 8. The L-1 Zond programme continued, with diminishing conviction, but no one proposed cancellation.

The government’s military industrial commission met three days later on 30th December. The commission underlined the value of unmanned lunar exploration and laid down a new official line on the moon programme. The Soviet Union had always planned to explore the moon by robots and would never risk lives for political propaganda. The Soviet media were invited to advertise the virtues of safer, cheaper unmanned probes. This was the first step in starting the myth, which was the official position for 20 years, that there never had been a moon race. There was little discussion of the moon-landing programme, which was now ready for the first launch of the N-1. A meeting of the party and government on the issue was set for a week later, on 8th January.