THE SPACESHIP TO CIRCLE THE MOON: THE L-l, ZOND

Preparations for the flight of Soyuz coincided with those of the Soyuz-derived L-1 cabin, which would fly a cosmonaut around the moon. The L-1 cabin was later called Zond, thus creating confusion with the engineering tests developed by Korolev as part of the interplanetary programme. Zond 1 had flown to Venus, Zond 2 to Mars, Zond 3 to the moon to test equipment for Mars and now Zond 4-8 would fill an important part in preparations to send cosmonauts around the moon.

From August 1964, the Soviet lunar programme had been divided between the around-the-moon programme (Proton, L-1/Zond) and the manned lunar landing (N-1, LOK, LK). When the State Commission on the L-1 met in December 1966, it set a date for the first manned circumlunar flight of 26th June 1967, to be preceded by four unmanned tests.

Zond was a stripped-down version of Soyuz. Its weight was 5,400 kg, length 5 m, span across its two 2 m by 3 m solar arrays 9 m, diameter 2.72 m and a habitable volume of 3.5 m3. It could take a crew of either one or two cosmonauts in its descent module. The sole engine was the 417 kg thrust Soyuz KDU-35 able to burn for about 270 sec, but it fired more thrusters than Soyuz. Its heatshield was thicker than Soyuz in order to withstand the high friction on lunar reentry at 11 km/sec. It carried an umbrella-like, long-distance, high-gain antenna and on the top a support cone, to which the escape tower was attached. Designer was Yuri Semeonov. The following were the main differences between Soyuz and L-1 Zond. Zond was:

• Smaller, without an orbital module.

• Maximum crew of two, not three.

• Instrument panel configured for lunar missions.

• Support cone at top.

• Long-distance dish aerial for communications.

• Thicker, heavier heatshield for high-speed reentry.

• Removal of docking periscope.

• Smaller solar panels.

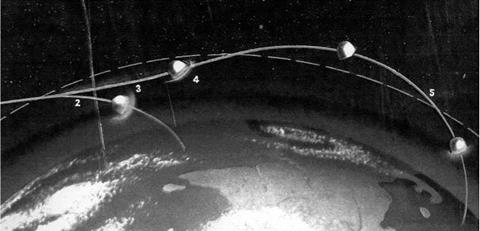

Theoretically, Zond could take three cosmonauts; but, without an orbital module it would be tight enough for two for the 6-day mission. The mission profile was for Proton to launch Zond into a parking orbit. On the first northbound equator pass, block D would ignite and send Zond to the moon. Zond would take three days to reach the moon, swing around the farside in a figure-of-eight trajectory and take three days to come home. The spacecraft would have to hit a very narrow reentry corridor. It would use Tikhonravov’s skip technique to bounce out of the atmosphere, killing the speed and then descend to recovery. The designers decreed that there should be four successful missions out to the moon, or a simulated moon, before putting cosmonauts on board for the mission.

An important distinction between Apollo on the one hand and the Soyuz, L-1/ Zond and LOK on the other was the high level of automation on Soviet spacecraft. As noted above, the Soviet Union decided to pave the way for a manned flight around the moon with no fewer than four automatic flights that precisely flew the same profile as the intended manned spacecraft. A comparable regime would have been followed for the LOK and a series of wholly automatic tests were set for the lunar lander, the LK and the block D upper stage. The Soyuz system was designed to achieve entirely automated rendezvous and docking in Earth orbit. All this required a high level of sophistication in control and computerized systems, something the Russians were rarely given the credit for. From the start, Korolev had built a high degree of automation into spacecraft, a decision which seems to have gone unchallenged

|

Cosmonaut Valeri Kubasov in Zond simulator |

and the early manned spaceship designs were finalized long before the first cosmonauts arrived. The head of cosmonaut training, General Kamanin, is known to have been privately critical of the high level of automation and the lack of scope given to cosmonauts to fly their own spacecraft. Zond carried the first computers used on Soviet spacecraft, the Argon series. Argon weighed 34 kg, light for its day and was the primary navigation system. It was assessed as having a reliability rate of 99.9% [12]. The Argon 11S was completed in 1968 in time for the Zond lunar missions. The cosmonauts would control the L-1 with a command system called Alfa, which had a 64-word read-write menu and 64 commands, with a choice of 4,096 words [13].

Although Zond was based on Soyuz, it had an entirely different control panel. As happened from time to time in the Soviet space programme, this came to light by accident. During the late 1970s, at a time when the Russians claimed ‘there had never been a moon race’, they released pictures of cosmonauts Vladimir Shatalaov and Valeri Kubasov in training, set against a background of what was presumed to be a Soyuz control panel. It must have escaped the censors that the control panel was entirely different from the Soyuz, with the Earth orbit orientation system taken out. The Zond control cabin comprised a series of caution and warning panels; cabin pressure, composition and electric meters; computer command systems; periscope; and translunar navigation systems.

The Soviet around-the-moon mission operated under a number of constraints, as follows:

• The moon should be high in the sky over the northern hemisphere during the outward and returning journey, so as to facilitate communications between Zond and the tracking stations, which were located on the Russian landmass.

• There should be a new moon, as viewed from Earth, with the farside illuminated by the sun. Zond should arrive at the moon when it was between 24 and 28 days old.

• The parking orbit must be aligned with the plane of the moon’s orbit.

• Reentry posed a real dilemma. Zond could reenter over the northern hemisphere, in full view of the tracking stations, but the long reentry corridor would bring the spaceship down over the Indian Ocean, where it would have to splash down. The cosmonauts would therefore be out of contact with the ground during this final phase, waiting for recovery ships to find them and pick them up.

• Alternatively, Zond could reenter over the Indian Ocean in the southern hemisphere, out of radio contact, but come down in the standard landing zone for Soviet cosmonauts in Kazakhstan. This offered a traditional landing on dry land, the prospect of being spotted during the descent and a quick recovery. Generally, this was the favoured approach and the one that would probably have been followed on a manned mission.

Opinions in the space programme were divided about the wisdom of splashdowns. Chief Designer Mishin was in favour, believing they presented no particular danger. Many others were against, arguing that the descent module was not very seaworthy,

|

The skip trajectory |

was difficult to escape in the ocean and could take some time to find. They also argued against the expense involved in having a big recovery fleet at sea.

The timing for Russian around-the-moon missions around the sun-Earth-moon symmetries was therefore quite complex [14]. To meet all these requirements, there are only about six launching windows, each about three days long and a month apart, each year. There can be long periods when there are no optimum conditions. There were no optimum launch windows for Zond to the moon between January and July 1969, the climax of the moon race. The scarcity of these opportunities explains why several L-1s (e. g., Zond 4) were fired away from the moon. Although these missions caused mystery in the West, the primary Russian interest was in testing navigation, tracking and the reentry corridor. Having the moon in the sky was not absolutely necessary for these things and since it was not available anyway, they flew these missions without going around the moon.

|

L-l/Zond |

|

|

Length |

5m |

|

Diameter |

2.7 m (base) |

|

Span |

9m |

|

Weight |

5,680 kg |

|

Habitable volume |

3.5m3 |

|

Engine |

One KDU-35 |

|

Fuel |

AK27 and hydrazine |

|

Thrust |

425 kg |

|

Specific impulse |

276 sec |

|

Block D |

|

|

Weight |

13,360 kg |

|

Fuel |

Oxygen and kerosene |

|

Thrust |

8,500 kg |

|

Specific impulse |

346 |

|

Length |

5.5 m |

|

Diameter |

3.7 m |

Source: Portree (1995); RKK Energiya (2001)

When the L-1 Zond was wheeled out for its first test – Cosmos 146, set for 10th March 1967 – the three-stage UR-500K Proton stood over 44 m tall and must have been a striking sight. The first two tests were called the L-1P, P for ‘preliminary’ indicating that a full version of Zond would not be used and that a recovery would not be attempted. The first stage would burn for 2 min with 894 tonnes of thrust. The second stage would burn for 215 sec. The third stage would place Zond or the L-1 in low – Earth orbit in a 250 sec burn. Finally, the Korolev block D fourth stage would fire 100 sec to achieve full orbit. One day after liftoff, the fourth stage, block D, would relight on the first northbound pass over the equator to send Zond out to a simulated moon [15].

Cosmos 146 was the fifth flight of Proton and the first with a block D. The block D’s single 58M engine had 8.7 tonnes of thrust and burned for 600 sec, enough to accelerate the payload to 11km/sec. In the event, block D successfully accelerated the cabin to near-escape velocity, with Cosmos 146 ending up in an elliptical high orbit reaching far out from Earth (though its ultimate path was not precisely determined). Signals and communications tests were carried out. This was an encouraging start to the L-1 programme, setting it on course for the first lunar circumnavigation by the target date of June 1967. Then the landing missions could get under way [16].

Cosmos 154 on 6th April 1967 was designed to repeat the mission to a simulated moon. This time the BOZ ignition assurance device failed during the ascent to orbit and was not in a position to control the block D stage for the simulated translunar burn, which could not now take place. This was a setback, now made worse by the crash of the related Soyuz spacecraft 20 days later and which raised questions about Zond’s control and descent systems. Zond’s parachute system was retested. When two such tests took place in Feodosiya in the Crimea, in June, the parachute lines snarled. Modifications took all summer. The programme underwent a thorough safety review in early September, being reviewed by an expert commission with nine working groups. Although Russia would have loved to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the revolution with a flight around the moon that November, the chances of doing so safely slipped further and further into the distance.

Working overtime, the designers and launch teams got the third L-1 Zond out to the pad by mid-September 1967. The countdown began for a launch on 28th September. The aim was to fly the L-1 Zond out to the moon and return for recovery at cosmic velocity, 11 km/sec, coming down 250 km north of Dzhezhkazgan on 4th October (or failing that in the Indian Ocean). The huge red-and-white Proton booster, weighing a record 1,028,500 kg, Zond cabin atop, tipped by a pencil spear of an escape tower, was taking with it Russia’s moon hopes. It sat squat on its giant pad, shrouded by its gantry, as engineers fussed with one technical problem after another. Yet it all went wrong. One of the six engines in the first stage of Proton failed to operate when a rubber plug was dislodged into the fuel line. At 60 sec the rocket veered off course and impacted 65 km downrange, but the Zond cabin was dragged free by the escape system. The cabin was found intact the next morning, though recovering it was difficult, for the toxic burning remains of Proton were all round about.

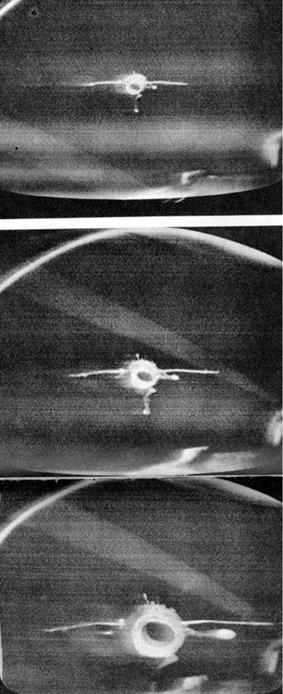

For the anniversary of the Revolution, the Russians were left with carrying out the mission that had been intended for Soyuz that April, but now without cosmonauts on board. What happened was important for the lunar programme, but not the kind of event that would bring throngs of excited crowds out onto the streets. Cosmos 186 was first to appear, beginning a series of flights that would requalify Soyuz for manned flight once more. It went up on 27th October and was followed three days later by Cosmos 188. Using totally automatic radar, direction-finding and sounding devices, Cosmos 186 at once closed in on 188 in the manoeuvre Komarov was to have carried out in April. The rendezvous and docking manoeuvres that followed went remarkably smoothly, although the double mission was plagued with other difficulties later. At orbital insertion, 188 was only 24 km away from its companion. Cosmos 186 closed rapidly, within two-thirds of an orbit. One hour later, over the South Pacific, they clunked together to form an automatic orbiting complex and 3.5 hours later they separated. Cosmos 186 was recovered the next day and 188 was deorbited on the 2nd November (it was blown up when it came down off course). Although not visually impressive to a spectacular-weary public, it was a display of advanced robotics. It proved the feasibility of first-orbit rendezvous, the viability of Soyuz-style docking and took some of the fears out of lunar orbit rendezvous when all this would have to be done a third of a million kilometres away.

However, the elation surrounding the Cosmos 186-188 mission was followed by a disheartening experience three weeks later. The next attempt to launch Zond, the fourth, was made very early on 23rd November and was aimed at a lunar flyby and recovery. The first stage behaved perfectly, but four seconds into the second-stage burn, one of the four engines failed to reach proper thrust. The automatic control system closed down the other three engines and the emergency system was activated. The landing rockets fired prematurely during the descent and the parachute failed to detach after landing, but the scratched and battered cabin was recovered. Proton itself crashed 300 km from where it took off.

The next L-1 Zond, the fifth, got away successfully on 2nd March, 1968. This time the UR-500K Proton main stages and block D worked perfectly. Zond 4 was fired 354,000km out to the distance of the moon, but in exactly the opposite direction to the moon, where its orbit would be minimally distorted by the moon’s gravitational field. The primary purpose of the mission was to test the reentry at cosmic velocity, so going round the moon itself was not essential. Cosmonauts Vitally Sevastianov and Pavel Popovich used a relay on Zond 4 to speak to ground control in Yevpatoria, Crimea.

The Zond 4 mission was not trouble-free and the first problems developed outbound. The planned mid-course correction was aborted twice because the astro – navigation system lost its lock on the reference star. When the correction did take place, it was extremely accurate and no more corrections were required. Zond 4 was supposed to dive into the atmosphere to 45 km, before skipping out to 145 km before making its main reentry. The tracking ship off West Africa, the Ristna, picked up signals from Zond indicating that the skip manoeuvre had failed and that it would make a steep ballistic descent, bringing it down over the Gulf of Guinea. On the insistence of the defence minister, Dmitri Ustinov, who was afraid that it might fall into foreign hands, the spacecraft was pre-programmed to explode if it made such a descent. Accordingly, Zond 4 was blown apart 10 km over the Gulf of Guinea. Not everyone was in agreement with this extreme approach to national security. It transpired that Zond 4 was actually 2 km from dead of centre in its reentry corridor (the tolerance was 10 km), but that a sensor had failed, preventing the skip reentry.

Some consolation could be drawn from a repeat of the Cosmos link-up of the previous winter. On 15th April 1968, Cosmos 212 (the active ship) linked to Cosmos 213, this time in a record 47min. Television showed the last 400m of the docking manoeuvre as they aligned their wing-like panels one with another. Millions saw the separation 3 hr 50 min later over the blue void of the Pacific.

|

Rendezvous in Earth orbit |

By the end of April 1968, the problems experienced by Zond 4 had been cured and the time was ready to try the first circumlunar flight to a ‘real’ moon this time. Launch took place on 23rd April. Unfortunately, 195 sec into the mission, the escape system triggered erroneously, shutting down all the Proton engines and flinging the Zond capsule clear, saving the cabin which came down 520 km away, but thereby wrecking the mission in the process. A replacement mission was planned for 22nd July, but in a bizarre pad accident in which at least one person died, block D and the L-1 toppled over onto the launch tower. Extracting the stages without causing an explosion took several nail-biting days. Further launchings were then postponed till the autumn.

The early L-1 Zond missions

10 Mar 1967 Cosmos 146

8 Apr 1967 Cosmos 154 (fail)

28 Sep 1967 Failure

23 Nov 1967 Failure

4 Mar 1968 Zond 4

23 Apr 1968 Failure

Requalification of Soyuz

27 Oct 1967 Cosmos 186

30 Oct 1967 Cosmos 188

14 Apr 1968 Cosmos 212

15 Apr 1968 Cosmos 213