Flying Again

Bob Rushworth’s last flight (2-45-81), on 1 July 1966, was also the first flight with full external tanks. As Johnny Armstrong later observed, "with 20-20 hindsight, flight 45 was destined for failure." On X-15A-2, the propellants in the external tanks were pressure-fed to the internal tanks, and the engine received propellants from the internal tanks in the normal fashion. The fixed-base simulator had shown that the X-15 would quickly become uncontrollable if the propellant from one external tank transferred while that from the other tank did not, because the moment about the roll axis would be too large for the rolling tail to counter. If this situation developed, the pilot would jettison the tanks, shut down the engine, and make an emergency landing.-1272

The problem was that, for this first flight with full tanks, there was no direct method to determine whether the tanks were feeding correctly. Instrumentation was being developed to provide propellant transfer sensors (paddle switches), but it was not available for this flight. Instead, a pressure transducer across an orifice in the helium pressurization line provided the only information. Researchers had verified that the pressure transducer worked as expected during a planned captive-carry flight (2-C-80) with propellants in the external tanks.-282

During the flight to the launch lake, while still safely connected to the NB-52, Rushworth verified that the pressure transducer was working. Rushworth jettisoned a small amount of propellant from the internal tanks, and NASA-1 watched the helium pressure come up as the external propellants flowed into the airplane (NASA-1 had to do it since nobody had thought to provide the pilot with any indicators). However, 18 seconds after the X-15 dropped away from the NB-52, Jack McKay (NASA-1) called to Rushworth: "We see no flow on ammonia, Bob." Rushworth responded, "Roger, understand. What else to do?" McKay: "Shutdown. Tanks off, Bob." Rushworth got busy: "OK, tanks are away… I’m going into Mud." Any emergency landing is stressful, but this one ended well. Bruce Peterson in Chase-2 reported, "Airplane has landed, everything OK, real good shape."282

Jettisoning the tanks with the "full" button was supposed to initiate only the nose cartridges and not fire the separation rockets. However, in this case, apparently because of faulty circuitry, the separation rockets did fire. Fortunately, the separation occurred without the tanks recontacting the airplane. Engineers obtained a great deal of data on the tank separation because an FM telemetry system in the liquid-oxygen tank transmitted data on accelerations and rotational rates during separation. Post-flight inspection of the ejector bearing points on the aircraft indicated that the ammonia tank briefly hung on the aircraft, marring the ejector rack slightly. The drogue chutes deployed immediately after separation and the dump valve in the tank allowed the propellants to flow out. The main chute deployment was satisfactory; however, the mechanism designed to cut the main chute risers failed and high surface winds dragged the tanks across the desert. Nevertheless, the Air Force recovered both tanks in repairable condition.-1282-

Bob Rushworth left the program after this flight, going on to a distinguished career that included a tour as the AFFTC commander some years later. Rushworth had flown 34 flights, more than any other pilot and more than double the statistical average. He had flown the X-15 for almost 6 years and had made most of the heating flights. These flights were perhaps the hardest to get right, and Rushworth did so most of the time.[283]

Major Michael J. Adams, making his first flight (1-69-116) on 6 October 1966, replaced Rushworth in the flight lineup. He started his career with a bang, literally. X-15-1 launched over Hidden Hills on a scheduled low-altitude (70,000 feet) and low-speed (Mach 4) pilot – familiarization flight. The bang came when the XLR99 shut itself down 90 seconds into the planned 129-second burn after the forward bulkhead of the ammonia tank failed. Fortunately, the airplane did not explode and Adams successfully landed at Cuddeback without major incident. Perhaps Adams was just having a bad day. After he returned to Edwards, he jumped in a T-38 for a scheduled proficiency flight. Shortly after takeoff, one of the J85 engines in the T-38 quit; fortunately, the Talon has two engines. Adams made his second emergency landing of the day, this time on the concrete runway at Edwards.-1284

|

|

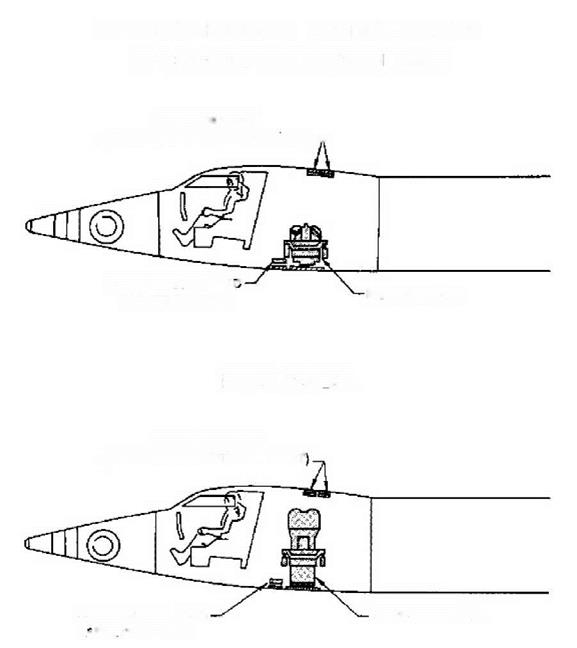

external tank transferred but the other one did not – the moment about the roll axis was too large for the rolling tail to counter. If this situation developed, the pilot would jettison the tanks, shut down the engine, and make an emergency landing. Unfortunately, this exact scenario played out on 1 July 1966 on the first flight with full tanks. Thankfully, Bob Rushworth managed to jettison the tanks and make an uneventful emergency landing at Mud Lake. (NASA)

Jack McKay seemed to have more than his share of problems, and holds the record for the most landings at uprange lakes (three). His last emergency landing was made during his last flight (168-113), on 8 September 1966. The flight plan showed this Smith Ranch launch going to 243,000 feet and Mach 5.42 before landing on Rogers Dry Lake. However, as McKay began his climb he noticed the fuel-line pressure was low. Mike Adams as NASA-1 recommended throttling back to 50% to see if the fuel pressure would catch up; it did not. McKay shut down the engine and began jettisoning propellants to land at Smith Lake. The landing was uneventful and NASA trucked the airplane back to Edwards.-285

The program had experienced a few flights where the pilot overshot the planned altitude for various reasons, but Bill Dana added one for the record books on 1 November 1966. On flight 356-83, Dana got the XLR99 lit on the first try and pulled into a 39-degree climb, or so he thought, heading for 267,000 feet. In reality, the climb angle was 42 degrees. Interestingly, Pete Knight in the NASA-1 control room did not notice the error either, and as the engine burned out he reported, "We got a burnout, Bill, 82 seconds, it looks good. Track and profile are looking very good." As Dana climbed through 230,000 feet, NASA-1 finally noticed and said, "[W]e got you going a little high on profile. Outside of that, it looks good." The flight eventually reached 306,900 feet-39,900 feet higher than planned.286

As Dana went ballistic over the top, he asked Knight if "Jack McKay [was] sending in congratulations." The reference was to flight 3-49-73 on 28 September 1965, when McKay had overshot his altitude by 35,600 feet. Dana had been NASA-1 on that flight and had needled McKay ever since. Dana’s fun, however, did not stop with the overshoot. As he reached to shut down the engine, Dana apparently bumped the checklists clipped to his kneepad with his arm. Dana later recalled, "At shutdown my checklist exploded. I don’t know how it came out of that alligator clamp, but anyway I had 27 pages of checklist floating around the cockpit with me, and it was a great deal like trying to read Shakespeare sitting under a maple tree in October during a high wind. I only saw one instrument at a time for the remainder of the ballistic portion… these will be in the camera film which I think we can probably sell to Walt Disney for a great deal." After an otherwise uneventful landing, Dana could not find the post-landing checklist, "Thank you, Pete," he joked. "Since my page 16 is somewhere down on the bottom of the floor, maybe you could go over the checklist with me?"287

1966 FLIGHT PERIOD

As was usual for the high desert during the winter, the rains had begun in late November 1966, and during early 1967 most of the lakebeds were wet, precluding flight operations. This gave North American and the FRC time to perform maintenance and modifications on the airplanes. For instance, X-15-1 was having its ammonia tank repaired and the third skid added, X-15A-2 was having instrumentation modified, and X-15-3 was having an advanced PCM telemetry system installed. By February the lakebeds at Three Sisters, Silver, Hidden Hills, and Grapevine were dry, and Rogers and Cuddeback were expected to be within two weeks. Unfortunately, snow and ice still covered Mud, Delamar, Smith Ranch, and Edwards Creek Valley. It would be late March before all the necessary lakes were dry enough to support flight operations.-1288!

The program was also making plans to add new pilots, allowing some of the existing pilots to rotate to other assignments. For instance, John A. Manke, a NASA test pilot, went through ground training and conducted a single engine run. Unfortunately, Mike Adams’s accident would eliminate any chance that Manke would ever fly the X-15.[289]

Pete Knight would eventually set the fastest flight of the program, but before that event he had at least one narrow escape while flying X-15-1. As he related in the pilot’s report after flight 1-73-

126:[290]

The launch and the flight was beautiful, up to a certain point. We had gotten on theta and I heard the 80,000-foot call. I checked that at about 3,100 fps. Things were looking real good and I was really enjoying the flight. All of a sudden, the engine went "blurp" and quit. There could not have been two seconds between the engine quit and everything else happening because it all went in order. The engine shut down. All three SAS lights came on. Both generator lights came on and then there was another light came on, and I think it was the fuel low line light. I am not sure. Then after all the lights got on, they all went out.

Everything quit. By this time, I was still heading up and the airplane was getting pretty sloppy. As far as I am concerned both APUs quit.

Once the X-15 began its reentry after an essentially uncontrolled exit, Knight managed to get one of the APUs started. Unfortunately, the generator would not engage, which meant Knight had hydraulics but no electrical power. He elected to land at Mud Lake.

Once I thought I was level enough I started a left turn back to Mud. Made a 6-g turn all the way around… Once I was sure I could make the east shore of Mud Lake with sufficient altitude I used some speed brakes to get it down to about 25,000 [feet altitude] and then varied the pattern to make the left turn into the runway landing to the west. On the final, all this time the trim was still at 5 degrees for the theta that we had. I was getting pretty tired of that side stick so I began to use both hands. One on the center stick and one on the side stick taking the pressure off the stick with the left hand and flying it with the right. Made the pattern and the airplane is a little squirrelly without the dampers but really not that bad. … I settled in and got it right down to the runway and it was a nice landing as far as the main skids were concerned, but the nose gear came down really hard.

After I got it on the ground I slid out to a stop. I started to open the canopy. I could not open the canopy. I tried twice and could not move that handle, so I sat there and rested for a while, I reached up and grabbed it again. Finally, it eased off and the canopy came open. Then I started to get out of the airplane and I could not get this connection off over here. I got the hat [helmet] off, to cool off a little bit, and tried it again. Then I was beginning to take the glove off to get a hand down in there also. I never did get that done. I tried it again and it would not come so I said the hell with it, and I’ll pull the emergency release. I pulled the emergency release and that headrest blew off and it went into the canopy and slammed back down and hit me in the head. I got out of the airplane and by that time, the C-130 was there. Got into the 130 and came home.

It was one of the few times an X-15 pilot extracted himself from the airplane without the assistance of ground crews. Normally a crew was present at each of the primary emergency lakes, but Mud was not primary for this flight and no equipment or personnel were stationed there.

Based on energy management, Knight probably should have landed at Grapevine. At the time, there was no energy-management display in the X-15, so NASA-1 made those decisions based on information in the control room. However, since the airplane had no power, and hence no

[2911

radio, decisions made by NASA-1 were not much help.

It is likely that the personnel on the ground were more worried than Knight was, because when the APUs failed they took all electrical power, including that to the radar transponder and radio. At the time, the radars were not skin tracking the X-15, so the ground lost track of the airplane. It was almost 8 minutes later when Bill Dana, flying Chase-2, caught sight of the X-15 just as it crossed the east edge of Mud Lake.[292]

The problem was most likely the result of electrical arcing in the Western Test Range launch monitoring experiment. Unlike most experiments, this one connected directly to the primary electrical bus. The arcing overloaded the associated APU, which subsequently stalled and performed an automatic safety shutdown. This transferred the entire load to the other APU, which also stalled because the load was still present. The APUs had been problematic since the beginning of the program, but toward the end they were generally reliable enough for the 30 minutes or so that they had to function. Each one was usually completely torn down and tested after each flight. In this case, something went wrong. After this flight, NASA moved the WTR and MIT experiments to the secondary electrical bus, which dropped out if a single generator shut down; this would preclude a complete power loss to the airplane.*293

Paul Bikle commented that Knight’s recovery of the airplane was one of the most impressive events of the program. The flight planners had spent many hours devising recovery methods after various malfunctions; all were highly dependent upon the accuracy of the simulator for reproducing the worst-case, bare-airframe aerodynamics. NASA constantly updated the simulator with the results from flights and wind-tunnel tests to keep it as accurate as possible. The flight by Knight was the only complete reentry flown without any dampers. As AFFTC flight planner Bob Hoey remembers, "[W]e would have given a month’s pay to be able to compare Pete’s entry with those predicted on the sim, but all instrumentation ceased when he lost both APUs, and so there was no data! Jack Kolf told Pete that we were planning to install a hand crank in the cockpit hooked to the oscillograph so he could get us some data next time this happened." Fortunately, it never happened again.*294

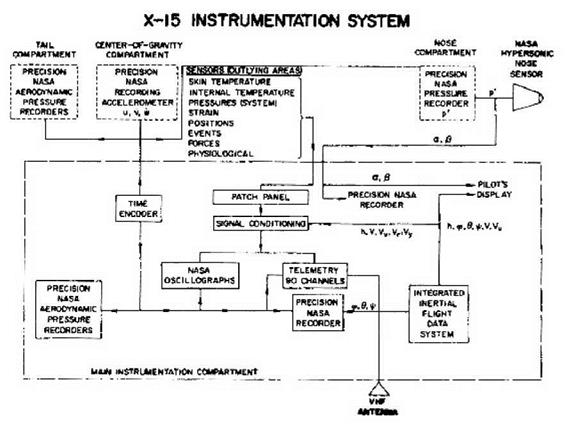

required for the operation of the NB-52s, other support and chase aircraft, propellant analysis and servicing, instrumentation, data processing and acquisition, photo lab, biomedical support, engineering, and test operations.

required for the operation of the NB-52s, other support and chase aircraft, propellant analysis and servicing, instrumentation, data processing and acquisition, photo lab, biomedical support, engineering, and test operations. The X-15 package for the cartographic program contained a KC-1 camera, an ART-15A stabilized mount, and photometric and environmental instrumentation to measure the conditions that prevailed during the time of the experiment. The KC-1 had been modified with a GEOCON I lens designed by Dr. J. Baker of Spica, Incorporated, to combine low distortion with relatively high acuity, and was adapted for operation at high altitude. The experiment package, minus the camera, weighed approximately 156 pounds. The KC-1 camera and lens added another 85-90 pounds depending on the film load, and occupied a space about 16 inches long by 18 inches wide by 21 inches high at the bottom of the instrument compartment. The GEOCON I low-distortion mapping lens had a focal length of 6 inches and a relative aperture of f/5.6, and could provide a resolution of 37 lines per millimeter on Super-XX film. North American modified X-15-1 to accept a KC-1 camera, including modification of the ART -15 mount and the addition of an 18- inch-diameter window that was 1.5 inches thick in the bottom of the instrument compartment. The film was nominally 9 by 9 inches, and 390 feet of it were stored in the magazine.-1106!

The X-15 package for the cartographic program contained a KC-1 camera, an ART-15A stabilized mount, and photometric and environmental instrumentation to measure the conditions that prevailed during the time of the experiment. The KC-1 had been modified with a GEOCON I lens designed by Dr. J. Baker of Spica, Incorporated, to combine low distortion with relatively high acuity, and was adapted for operation at high altitude. The experiment package, minus the camera, weighed approximately 156 pounds. The KC-1 camera and lens added another 85-90 pounds depending on the film load, and occupied a space about 16 inches long by 18 inches wide by 21 inches high at the bottom of the instrument compartment. The GEOCON I low-distortion mapping lens had a focal length of 6 inches and a relative aperture of f/5.6, and could provide a resolution of 37 lines per millimeter on Super-XX film. North American modified X-15-1 to accept a KC-1 camera, including modification of the ART -15 mount and the addition of an 18- inch-diameter window that was 1.5 inches thick in the bottom of the instrument compartment. The film was nominally 9 by 9 inches, and 390 feet of it were stored in the magazine.-1106! SPECTROMETER

SPECTROMETER