MiG-23 / 9-01 to 9-12

After the MiG-23 multipurpose fighter and the MiG-25 interceptor, the MiG engineers became aware of new trends in fighter development and studied the lessons of two decades of local military conflicts. They focused their thoughts on the next-generation aircraft: a highly maneuverable frontline fighter that would remain true to the long-standing MiG tradition of the MiG-15 and MiG-21. This aircraft had to be the end

|

The 9-01, the first prototype of the MiG-29, without the fin extensions forming ventral fins (a la Su-27) that normally characterize it.

|

A large mudguard was necessary on the 9-01 because of the forward location of the front gear leg, which greatly increased the risk of foreign objects being sucked into the engine air intakes.

At first the MiG-29 was armed with a twin-barrel cannon, hence the two ports visible on the port side of the fuselage’s blended area

product of the latest advances in technology, supplemented by the OKB’s customary savoir-faire.

Some very peculiar external considerations influenced their decisions. The new fighter was intended to counter a trio of American fighters developed during the 1960s and 1970s: the F-15, F-16, and F-18. Needless to say, the engineers had set for themselves the goal of developing an aircraft that would not only meet the requirements of the Soviet air force but also become a tough competitor on the international market. Their aim would be achieved

The LFI project (Legkiy Frontovoy Istrebityel frontline light fighter) was launched in the early 1970s. The specification asked for a fighter capable of the following tasks:

1 Destroying hostile fighters in air combat, thus demonstrating air superiority

2. Destroying hostile aircraft, attacking troops and targets on the front line

3. Destroying enemy reconnaissance, AW ACS, and ECM aircraft

4 Protecting aircraft bound for other missions

5. Opposing all of the enemy’s aerial observation assets

The aircraft should also be available for reconnaissance missions and for ground support missions against small targets, under visual flight rules and with such weapons as bombs, rockets, and cannons.

The LFI gave rise to a number of quite different proposals for the aircraft’s overall architecture One called for lateral air intakes to feed two turbojets housed in the fuselage, a la MiG-25 As is now widely recognized, the layout finally selected was particularly original, and no fewer than nineteen prototypes (numbered 9-01 to 9-19) were needed to develop the engine, all of the systems, and some variants.

The MiG-29’s architecture was called “integral aerodynamic design" by the Soviets It had no fuselage, or at least nothing recognizable as one by contemporary standards; but it could carry a lot of weight (twice what the previous generation of fighters could), had a wide flight envelope, and was capable of sustained maneuvers up to 9 g. The high thrust-to-weight ratio (1.1) allows excellent takeoff performance and vertical climbs in building up speed. Its rational architecture, thrust-to-weight ratio, and safe automatic flight control system give the MiG-29 outstanding maneuverability. Piloting the aircraft is simple and “comfortable”—an achievement that can be credited to several of R. A. Belyakov’s close assistants, namely, A. A. Chu- machenko, V. A. Lavrov, and M. R. Valdenberg.

The wing shows a leading edge sweep of 42 degrees on outer panels and has a 3 5 aspect ratio. Its outstanding lift capability is the result

of various lift devices: wing twist, computer-controlled maneuvering flaps (programmed for different flight regimes) across the leading edge, and plain trailing edge flaps. The aerodynamic design helps to unload the wing significantly, because 40 percent of the effective lift is provided by the lift-generating center part of the fuselage

The wing contains two integral tanks, each with a capacity of 350 1 (92 US gallons). The center body—it should be considered more a lifting body than a fuselage—consists of (from nose to tail) the radar and its radome, the forward electronics compartment, the cockpit and the lower electronics compartment, the rear electronics compartment, fuel tank no. 1 (705 1 [186 US gallons]), fuel tank no. 2 (875 1 [231 US gallons]), fuel tank no 3 (1,8001 [476 US gallons]), the engine bay, and fuel tank no. ЗА (285 1 [75 US gallons]). The center body’s leading edge features a sweep angle of 73 degrees, 30 minutes. In the center of the boat-tail and the engine nozzle throats, the tail chute is placed in the middle of the jaws formed by the two-cylinder actuated, forward – hinged airbrakes (one opens upward, the other downward) Tanks nos. 1 and 3 form a major carry-through double stress box of the body structure that is made of aluminum-lithium, measures 3,105 x 3,000 x 830 mm (122.2 x 118.1 x 32.7 inches), and weighs 220 kg (485 pounds)

The cockpit is fitted with the 10-degree-inclined K-36DM zero/zero ejection seat, and the pilot has a forward angle of vision limited to 14 degrees Three internal mirrors provide rearward view. The vertical tail surfaces are carried on slim booms alongside engine nacelles. The tail fins are canted 6 degrees outward Their leading edge (featuring a sweep angle of 47 degrees, 50 minutes) can be extended forward to form overwing fences that contain BVP-30-26M flare launchers.

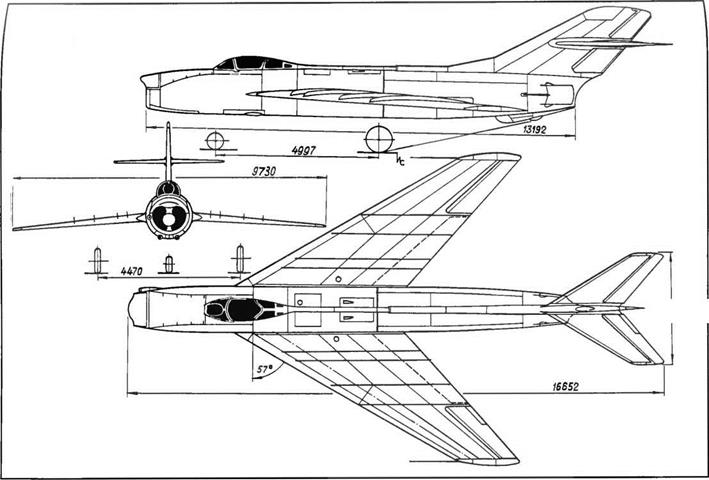

Compared to that of the prototype and first-series aircraft, the rudder was made larger by extending its chord. Some of the prototypes, including the 9-01 and a few production aircraft, had two ventral fins, they were quickly removed The all-moving horizontal tail surfaces on either side of the booms that carry the fins travel between +15 and -35 degrees (either symmetrically or differentially). The total span of the horizontal tail surfaces is 7.78 m (25 feet, 6.3 inches), and their sweep angle at the leading edge is 50 degrees.

The gear is of the retractable tricycle type. The nose gear has two driven wheels (tires 570 x 140 mm) and retracts rearward between the engine air intakes. On prototype 9-01 the longer front leg was hinged farther forward—practically under the pilot’s seat—and held gear door elements. There was a big mudguard to the rear of the prototype’s nosewheels that was later reduced in size to avoid any cramming effect. The nosewheels are steerable: plus or minus 8 degrees for taxiing, takeoffs, and landings, plus or minus 30 degrees for slow ground maneuvers. The main gear retracts forward into the wing roots, the

This interesting photograph shows the unexpected comeback on prototype 9-17 of ventral tail fins, which never seemed to disappear once and for all.

This first-series MiG-29 carries six air-to-air missiles—two R-27s and four R-60s Note the peculiar shape of the mudguard; it will later be modified.

wheels (tires 840 x 290 mm) turning 90 degrees to lie flat above the legs. The gear is hydraulically powered and can be extended mechanically in case of emergency

The power plant consists of two RD-33 two-spool turbofans developed by the Klimov ОКБ. Each is rated at 4,940 daN (5,040 kg st) dry and 8,135 daN (8,300 kg st) with afterburner and fed by two ducts that reveal a very distinctive feature Because this fighter was designed to operate from rough strips near the front Ime, the engine ducts are canted slightly and have wedge intakes that stand away from the lower part of the center body to form a boundary layer bleed. They also house a multisegment ramp that allows the pilot to modify the ducts’ size to suit the aircraft’s speed and flight conditions up to the maximum indicated airspeed of 1,500 km/h (810 kt) or Mach 2.3. The overall internal fuel capacity—4,365 1 (1,153 US gallons)— can be complemented by a 1,500-1 (396-US gallon) auxiliary tank located under the fuselage, between the engine ducts.

This ramp device includes a top-hinged, perforated forward door that closes the duct while the aircraft is taxiing, taking off, or landing At that point the engines are fed mainly via louvers on top of the outer parts of the center body and via the perforations of the door When the aircraft’s speed reaches 200 km/h (108 kt) at takeoff the nose gear’s shock strut expands and opens the door, compression of the same shock strut at touchdown closes the door. Both engines are thus protected against foreign object damage (FOD) The louvers also have an air inlet control function, sometimes disymmetncal, and behind them are three lattice ports that are in fact spill doors.

Both engines drive the accessory gearbox The GTDE-117 auxiliary power unit is a small turbine engine weighing 40 kg (88 pounds) and delivering 98 ch equivalent shaft horsepower to start the turbofans or 70 ch for other duties. The air scoop for this APU can be seen above the rear fuselage on port side. Exhaust passes through the underbelly fuel tank when in place There is a single-point pressure refueling through receptacle in the port wheel well but there are also overwing receptacles for manual gravity fueling

The mechanical flying controls, hydraulically powered and outstandingly efficient, ensure steadiness throughout the flight envelope The pilot thus can reach the appropriate angle of attack and load factor quickly—a point of the utmost importance for a fighter Moreover, they can be serviced by field support crews This flight control system includes an AOA limiter set at 26 degrees to prevent spins and roll-offs and to maintain control of the roll and pitch attitude. In symmetrical maneuvers that do not involve banking, an AOA of 30 degrees can be safely reached

During flight demonstrations of the MiG-29 at Farnborough in 1988, specialists noticed with interest its 360-degree sustained level

This photograph of prototype 9-10 emphasizes the cleanness of the MiG-29 s “integral aerodynamic design.”

The 9 17 was used for testing larger rudders Here, it carries overwing fin extensions containing IRCM flare launchers

Exploded view of the MiG-29. (1) Radome. (2) Forward electronics compartment. (3) Nose gear strut. (4) Cockpit and lower electronics compartment. (5) Apex. (6) Air intake duct (7) Main gear leg. (S) Leading edge flaps (9) Aileron. (10) Flaps. (11) Wing box. (12) Port engine cowling. (13) Fuel tank no. ЗА. (14) Rear bay. (15) Slab tailplane. (16) Rudder (17) Tail fin. (18) Eng ne access panels (19) Fuel tank no. 3. (20) Panels and walls of fuel tank no. 2 (21) Fuel tank no. 1 (22) Air intake louvers. (23) Access panels and walls of the central equipment bay (24) Cockpit canopy. (25) Windshield (MiG OKB document) This view depicts one of the early production aircraft as indicated by the gear door element on the nose gear strut smaller wheels (530 x 100 for the nosewheels. 770 x 200 for the mam gear), smaller rudders five-section leading edge flaps, and two section ailerons and flaps

|

On recent production aircraft the base of the nose probe is fitted with small vortex generators.

|

turns as well as its 350-m (1,150-foot) radius of turn at 800 km/h (432 kt) and its 225-m (740-foot) radius of turn at over 400 km/h (216 kt)— with, in both cases, a 3.8 load factor. In a sustained level turn at 10,000 m (32,800 feet) and Mach 0.9, both the pilot and the airframe had to withstand between 4.6 and 5 g.

If turn rate is essential to a fighter, linear acceleration is even more so. That of the MiG-29 at Mach 0.85 at sea level is 11 m/sec2 (36 ft/sec2), which means that the aircraft needs 13 seconds to accelerate from 500 to 1,000 km/h (270 to 540 kt). Its linear acceleration is still 6.5 m/sec2 (21.3 ft/sec2) at Mach 0.85 at 6,000 m (19,680 feet).

|

On production aircraft the front gear strut was moved back to between the engine air intakes The mudguard was replaced by a simple scraper

|

The SUV multiform fire control unit is one of the most interesting features of the MiG-29 For the first time anywhere, a fighter was equipped with a fire control unit that employed three different channels for target acquisition, pulse Doppler radar linked to a laser range finder, infrared search and tracking system (IRST), and helmet-mounted target designator. All of these systems work together with the help of on-board computers The fire control system is thus entirely automatic, ensuring efficiency and discretion at the time of attack and increasing the combat capabilities of the aircraft as it engages hostile targets in a countermeasure environment. The IRST system measures

|

The whole MiG-29 optoelectronics suite (KOLS) is contained in this small ball, located in front of the windshield: infrared search-and-track system plus laser range finder

|

the target coordinates with the highest accuracy; the first salvo of cannon shells seldom if ever fails to hit its objective.

The N 019/RP-29 (Sapfir 29) pulse Doppler radar can acquire a target with the radar cross-section of another fighter at a distance of 100 km (62 miles) and track it to within 70 km (44 miles). It can also track ten hostile aircraft simultaneously but has no mapping mode. The helmet-mounted target designator is used for off-axis direction of air-to-air missiles.

Standard weaponry includes either six R-60T or R-60MK IR-guided close-range air-to-air missiles or four R-60s and two R-27R-1 radar-guided medium-range (50-70 km [31-44 miles]) air-to-air missiles at six wing store stations. But it can also carry other weapons such as R-73A/R-73E close-range air-to-air missiles, which can be fired as long as the load factor is under 8. The missiles’ homing heads are hardened against enemy ECM

The cannon armament is limited to a single 30-mm GSh-301 with 150 rounds. It is located in the forward part of the port glove formed by the center body ahead of the wing (the 9-01 prototype had a twin-barrel cannon at the same place). The maximum war load of 3,000 kg (6,600 pounds) may also include four FAB-500 or eight FAB-250 bombs, four B-8M-1 rocket pods (20 x 80 mm), four S-24B 240-mm rockets, four 3B-

Takeoff of a MiG-29 The gear is not yet fully retracted, and the leading edge flaps are still extended but the trailing edge flaps have already retracted and the slab tailplane is deflected upward This aircraft has only four store stations instead of the usual six

This MiG-29 (9-10) still has the older type of rudders and carries six air-to-air missiles (two R-27s and four R-60s).

500 napalm bombs, four KMGU-2 submunitions dispensers, or a combination of these weapons.

The MiG-29 was first piloted on 6 October 1977 by A. V. Fedotov. The aircraft’s official acceptance certificate was signed in 1984, but mass production had started as early as 1982. The MiG-29 was photographed by a U. S. satellite in November 1977 at the Ramenskoye flight test center and given the provisional Western designation Ram-L The second prototype was flown in early June 1978 and lost due to engine fire on 15 June with Menitskiy at the controls; the pilot was saved by its KM-1 ejection seat. The fourth prototype was lost with Fedotov at the controls on 31 October 1980 due to engine problems also, and once more the pilot was saved by the ejection seat.

In June 1983, when the first MiG-29s were delivered to the air regiments, 2,000 test flights had taken place. The aircraft was continuously updated, and if not for the recent events in the ex-USSR it could have had a bright future. The production version did correspond to the izdeliye 9-12 standard.

The MiG-29 was exported to eleven countries: Cuba, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, India, Iran, Iraq, North Korea, Poland, Rumania, Syria, and Yugoslavia. It is interesting to note that eighteen single – seaters and five two-seaters delivered to the former East Germany are now flown by pilots of the 5th Luftwaffe division in the FRG.

Specifications

Span, 11.36 m (37 ft 3.2 in); overall length, 17.32 m (56 ft 9.9 in); fuselage length, 14.875 m (48 ft 9.6 in); height, 4.73 m (15 ft 6.2 in); wheel track, 3.09 m (10 ft 1.7 in); wheel base, 3.645 m (11 ft 11.5 in); wing area, 38 m2 (409 sq ft); takeoff weight, 15,240 kg (33,590 lb); max takeoff weight, 18,500 kg (40,775 lb); wing loading, 401-486.8 kg/m2 (82.2-99.7 lb/sq ft); max operating limit load factor, 9 at < Mach 0.85; 7 at > Mach 0.85.

Performance

Max speed at sea level, 1,500 km/h (810 kt); max permissible operating speed, 2,450 km/h or Mach 2.3; takeoff speed, 220 km/h (119 kt); approach speed, 260 km/h (141 kt); landing speed, 235 km/h (127 kt); climb rate at sea level, 330 m/sec (64,945 ft/min); service ceiling, 17,000 m (55,760 ft); range in clean configuration, 1,500 km (930 mi); with 1,500-1 (396-US gal) auxiliary tank, 2,100 km (1,300 mi); takeoff roll, 260 m (855 ft) with afterburner, 600 m (1,970 ft) without afterburner; landing roll with tail chute, 600 m (1,970 ft)

|

This photograph depicts the wide-screen periscope of the MiG-29UB in its folded disposition Notice the two rearview mirrors on the canopy post

|