THE MISSION

What would a Russian Zond around-the-moon mission have been like? The Proton rocket would have been fuelled up about eight hours before liftoff. This is carried out automatically, pipes carrying the nitric acid and UDMH into the bottom stages, liquid oxygen and kerosene into block D. The crew – Alexei Leonov and Oleg Makarov for the first mission – would have gone aboard 2.5 hours before liftoff. Dressed in light grey coveralls and communication soft hats, standing at the bottom of the lift that would bring them up to the cabin, they would have offered some words of encouragement to the launch crews overseeing the mission. The payload goes on internal power from two hours before liftoff. The pad area is then evacuated and the tower rolled back to 200 m distant, leaving the rocket standing completely free. There may be a wisp of oxidizer blowing off the top stage, but otherwise the scene is eerily silent, for these are storable fuels. The launch command goes in at 10 sec and the fuels start to mix with the nitric acid. This is an explosive combination, so the engines start to fire at once, making a dull thud. As they do so, orange-brown smoke begins to rush out of the flame trench, the Proton sitting there amidst two powerful currents of vapour pouring out from either side. As the smoke billows out, Proton is airborne, with debris and stones from the launch area flying out in all directions. Twelve seconds into the mission, Proton rolls over in its climb to point in the right direction. A minute into the mission Proton goes through the sound barrier. Vibration is now at its greatest, as are

|

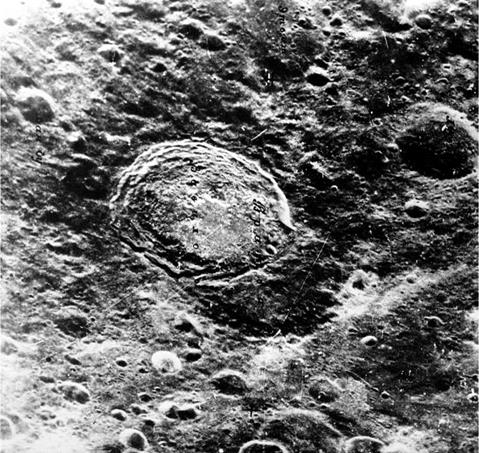

Remarkably, Zond 6 images survived |

the G forces, 4 G. The second-stage engines begin to light at 120 sec, just as the first – stage engines are completing their burn. Proton is now 50 km high, the first stage falls away and there is an onion ring wisp of cloud as the new stage takes over. Proton is now lost to sight and those lucky enough to see the launch go back indoors to keep warm. Then, 334 sec into the mission, small thrusters fire the second stage downward so that the third stage can begin its work. It completes its work at 584 sec and the rocket is now in orbit.

Once in orbit, the precise angle for translunar injection is recalculated by the instrumentation system on block D. The engine of block D is fired 80 min later over the Atlantic Ocean as it passes over a Soviet tracking ship. The cosmonauts would have experienced relatively gentle G forces, but in no time would be soaring high above Earth, seeing our planet and its blues and whites in a way that could never be imagined from the relative safety of low-Earth orbit. At this stage, with Zond safely on its way to the moon, Moscow Radio and Television would have announced the

|

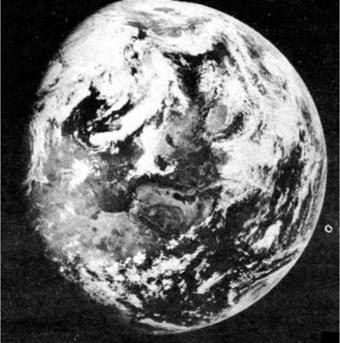

Leaving Earth, now 70,000 km distant |

launching. Televised pictures would be transmitted of the two cosmonauts in the cabin and they would probably have pointed their handheld camera out of the porthole to see the round Earth diminish in the distance. The spaceship would not have been called Zond. Several names were even tossed around, like Rossiya (Russia), Sovietsky Rossiya (Soviet Russia) and Sovietsky Soyuz (Soviet Union), but the favourite one was the Akademik Sergei Korolev, dedicating the mission to the memory of the great designer.

Day 2 of the mission would be dominated by the mid-course correction. This would be done automatically, but the cosmonauts would check that the system appeared to be working properly. Although the Earth was ever more receding into the distance, the cosmonauts would see little of the moon as they approached, only the thin sliver of its western edge. Zond’s dish would be pointed at Earth for most of the mission in any case.

Highlight of the mission would be at the end of day 3. Zond would fall into the gravity well of the moon, gradually picking up speed as it approached the swing-by, although this would be little evident in the cabin itself. Then, at the appointed moment, Zond would dip under the southwestern limb of the moon. At that very moment, the communications link with ground control in Yevpatoria would be lost, blocked by the moon. The spaceship would be silent now, apart from the hum of the airconditioning. For the next 45 min, the entire face of the moon’s farside would fill

|

Earthrise for Zond 7 |

their portholes, passing by only 1,200 km below. The commander would keep a firm lock on the moon, while the flight engineer would take pictures of the farside peaks, jumbled highlands and craters, for the farside of the moon has few seas or mare. As they soared around the farside, the cosmonauts would be conscious of coming around the limb of the moon. The black of the sky would fill their view above as the moon receded below. As they rounded the moon, they would have seen a nearly full round Earth coming over the horizon, not the crescent enjoyed by Apollo 8. The Akademik Sergei Korolev would reestablish radio contact with Yevpatoria. This would be one of the great moments of the mission, for the cosmonauts would now describe everything that they saw below and presently behind them and as soon as possible beam down television as well as radio. Their excited comments would later be replayed time and time again.

A mid-course correction would be the main feature at the end of day 4. The atmosphere would be relaxed, after the excitement of the previous day, but in the background was the awareness that the most dangerous manoeuvre of the mission lay ahead. The course home would be checked time and time again, with a final adjustment made 90,000 km out, done by the crew if the automatic system failed. The southern hemisphere would grow and grow in Zond’s window. Contact with the ground stations in Russia would be lost, though attempts would be made to retain communications through ships at sea. The two cosmonauts would soon perceive Zond to be picking up speed. Strapping themselves in their cabin, they would drop the service module and their own high-gain antenna and then they would tilt the heat – shield of their acorn-shaped cabin at the correct angle in the direction of flight. This was a manoeuvre they had practised a hundred times or more. Now they would feel the gravity forces again, for the first time in six days, as Zond burrowed into the atmosphere. After a little while, they would sense the cushion of air building under Zond and the spacecraft rising again. The G loads would lighten and weightlessness would briefly return as the cabin swung around half the world in darkness on its long, fast, skimming trajectory. Then the G forces would return as it dived in a second occasion. This time the G forces grew and grew and the cabin began to glow outside the window as it went through the flames of reentry, ‘like being on the inside of a blowtorch’ as Nikolai Rukhavishnikov later described reentry. Eventually, after all the bumps, there was a thump as the parachute came out, a heave upward as the canopy caught the air and a gentle, swinging descent. As the cabin reached the flat steppe of Kazakhstan, retrorockets would fire for a second underneath to cushion the landing. On some landings the cabin comes down upright, on others it would roll over. Hopefully, the helicopter ground crews would soon be on hand to pull the cosmonauts out. What a story they would have to tell! What a party in Moscow afterwards! The charred, still hot Akademik Sergei Korolev would be examined, inspected, checked and brought to a suitable, prominent place of reverence in a museum to be admired for all eternity.