In 2004, NASA had announced that it intended to stop funding ISS in 2016, as the Administration turned its attention to the Orion spacecraft, the Ares-1 launch vehicle, and the ultimate return of human astronauts to the lunar surface. Three years later, in April 2007, NASA Administrator Michael Griffin announced that ISS

was to be included in NASA’s budget requests through 2020. Griffin stated: “The partners have been working for a decade and a half to put in place these four laboratories. I don’t think political leaders in 2016 will end their involvement. Assets like the ISS live a lot longer than anticipated. I doubt it will turn into a pumpkin in 2016.’’

In mid-2007, Roscosmos announced that they had no plans to co-operate with NASA on Project Constellation until at least 2015. The Russians said that their budget had been allocated so as to allow them to support NASA’s commitment to ISS until that time, during which they would re-commence lunar exploration with robotic probes while supporting India’s and China’s robotic lunar exploration programmes. After 2015 ,Russia would be free to reconsider their position regarding Project Constellation. Meanwhile, the Russians continued to talk about building science modules for the ISS, but no new modules had been completed, as yet.

On February 26, STS-117 had been delayed by damage to the ET caused by hailstones while it stood on the launchpad. The delay caused the Shuttle’s launch programme to be rescheduled yet again:

|

STS-117 Atlantis

|

July 8, 2007

|

S-3/S-4 Truss structure

|

|

STS-118 Endeavour

|

August 9, 2007

|

S-5 Truss structure

|

|

STS-120 Discovery

|

October 20, 2007

|

Harmony

|

|

STS-122 Atlantis

|

December 2007

|

Columbus

|

All subsequent flights were similarly delayed.

At the same time NASA announced that they would swap the orbiters assigned to three of those flights in order to ease the pressure in the schedule:

• STS-120 would now use Discovery rather than Atlantis.

• STS-122 would use Atlantis rather than Discovery.

• STS-124 would use Discovery rather than Atlantis.

The rescheduling meant that plans to retire Atlantis in 2008 and cannibalise it to provide spare parts for Discovery and Endeavour had been changed.

NASA also announced that it had added $719 million to its contract with Roscosmos to purchase additional Soyuz TMA flights for American astronauts, to deliver and recover Expedition crews, during the period between the last Shuttle flight in 2010 and the first flight of the Orion/Ares-1 combination to ISS, currently scheduled for 2015. Despite this schedule, continual failure to make the promised annual increase to NASA’s budget to support Project Constellation made that date seem highly unlikely.

Asked previously if the Shuttle would continue to fly beyond the announced 2010 deadline set by President Bush, NASA Administrator Michael Griffin had made a one word reply, “No!” That, added to the 2007 schedule delays, meant that NASA would have to concentrate the remaining Shuttle flights on delivering the primary ISS elements into orbit before the Shuttle stopped flying in 2010. Any planned Utility flights, to support ISS operations, might yet prove to be expendable.

|

STS-117 DELIVERS THE STARBOARD-3/4 ITS

|

STS-117

|

|

COMMANDER

|

Rick Sturckow

|

|

PILOT

|

Lee Archambault

|

|

MISSION SPECIALISTS

|

Patrick Forrester, Steven Swanson, John Olivas,

|

|

James Reilly

|

|

EXPEDITION-15/16 (up)

|

Clayton Anderson

|

|

EXPEDITION-14/15 (down)

|

Sunita Williams

|

|

A thunderstorm passed over KSC on February 26, and hailstones “the size of golf balls” struck the foam exposed at the top of STS-117’s ET, leaving visible damage. They also damaged approximately 25 tiles on the orbiter’s left wing. The Shuttle stack was rolled back to the VAB for inspection and repair. and the planned March 15 launch was cancelled and rescheduled for no earlier than May 11, 2007. That date slipped back to June as NASA and contractor engineers ensured that the ET was safe to use. Shuttle programme manager Wayne Hale told journalists:

“The speculation that a lot of people have engaged in is that the last flight of the Shuttle to the space station will get pushed out of 2010. That just will not happen due to this problem.’’

He further stated:

“There might be some small effect to a couple of the later flights, but by the time we roll around to the end of the year, I expect we would be fully able to catch up.’’

The Shuttle was rolled back to LC-39A on May 15, with lift-off scheduled for June 8. On that date, Atlantis lifted off into the twilight, at 19: 38, beginning the first of four Shuttle flights planned for 2007. In the payload bay was the S-3/S-4 ITS, which would be mounted on the S-1 ITS and deployed during a series of three EVAs. The second set of SAWs on the P-6 ITS would then be retracted into its storage box, in order to allow the S-3/S-4 SAWs to rotate as they tracked the Sun.

Mission Commander Rick Sturckow had previously reviewed the work of earlier crews that had worked with the ITS elements on ISS at a prelaunch press conference, saying, “We’re really fortunate that we have those guys to follow. Almost everything went great on those missions, and the things that didn’t go so well, we’re able to learn from.’’

To overcome any repeat of the difficulties experienced on STS-115, such as when a bolt locking the SARJ in its launch position had taken much longer than planned to remove Sturckow explained:

“We have a torque multiplier… that they didn’t have. So if we do encounter the same difficulty with high torques that they had, we’ll break out this tool. And we’ll apply whatever torque it takes to break the bolt or back it out at the higher torque settings. So I don’t have any doubt that we’ll be able to remove those launch restraints.’’ He added, “When you’re doing assembly operations, everything that you plan to do is contingent on the flight prior to you and the hardware that’s already in orbit.’’

The STS-117 ascent into orbit was flawless, with no obvious signs of foam falling away from the ET in video of the launch. However, while video of the jettisoned ET showed that repairs to the hail damage had remained in place, one piece of foam, approximately 15cm x 8cm was missing. Orbital insertion was followed by the deployment of the payload bay doors and the Ku-band antenna. On ISS, Yurchikhin, Kotov, and Williams watched the launch on a video uplink from Houston.

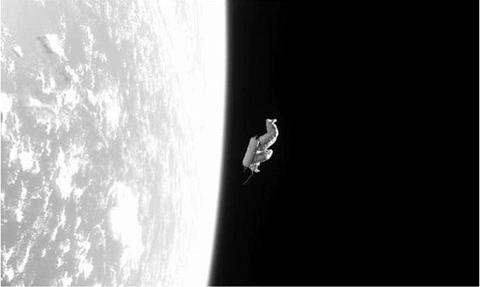

In the latter part of the day, Forrester and Swanson activated the RMS, to test its function. As they raised the arm from its cradle they noticed that an area of insulation blanket near the port OAMS pod pulled away from the adjacent thermal tiles. Video cameras on the RMS were used to relay views of the 10 cm by 7 cm area to Houston. Similar damage had been identified on Discovery during two earlier flights and both had returned to Earth without incident. Initial reviews of the images of the blanket suggested that the airflow over the OAMS pod during the early phases of the launch had lifted the edge of the blanket and caused it to fold back on itself. Other options included: bad installation of the blanket during processing, or impact damage during launch. The Shuttle crew began their sleep period at 01: 38, June 9.

Day 2 began with a wake-up call at 10: 10 that morning. Archambault, Forrester, and Swanson activated the RMS, mounted the OBSS in the end-effector, and completed the first inspection of Atlantis’ TPS. Prior to placing the OBSS back along the door hingeline, the cameras were used to view the port OAMS pod, with the detached insulation blanket. John Shannon, of the Mission Management team told a press conference, “If we decide this is a problem, we have a lot of capabilities to go address it.’’ He made it clear that Atlantis carried the equipment necessary to repair the blanket, by folding it flat and pinning it in place. While the video inspection was underway, Olivas, Reilly, and Anderson inspected the EMUs that they would use during the flight’s three EVAs. During the day the crew also extended the docking ring and installed the centreline video camera that would allow Archambault to see PMA-2 during the final approach to docking.

Following a second sleep period, June 10 began at 09 : 08. During the morning Olivas used a 400 mm lens on a digital camera to record the lifted corner of the thermal blanket on the port OAMS pod through the flight deck aft windows. The photographs had been requested during the morning briefing given to the crew by controllers in Houston. The written daily briefing was sent up to the crew and

|

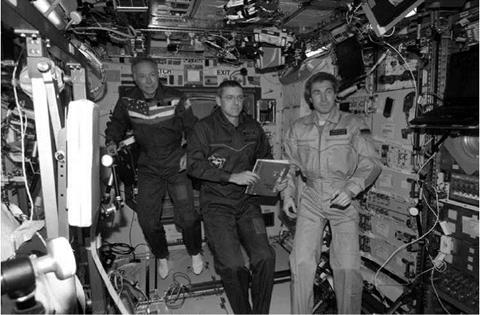

Figure 88. STS-117 crew (L to R): Clayton C. Anderson, James F. Reilly, II, Steven R. Swanson, Frederick W. Sturckow, Lee J. Archambault, Patrick G. Forrester, John D. Olivas.

|

|

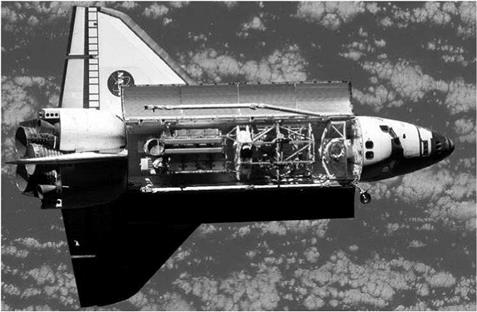

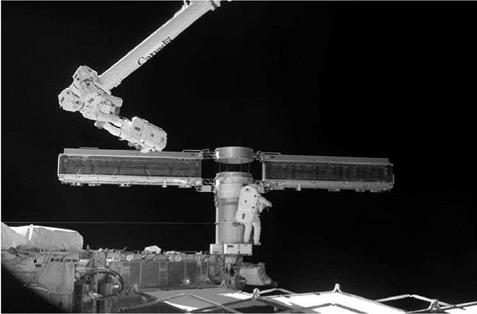

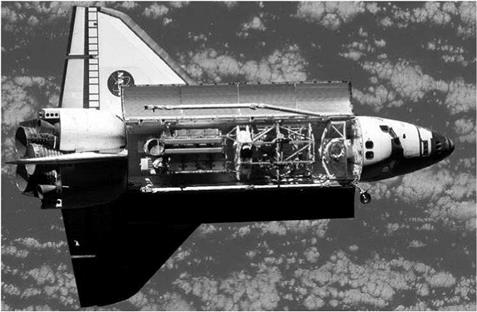

Figure 89. STS-117 delivers the S-3/S-4 Integrated Truss Structure to ISS.

|

included the reassurance that, “Although this [damage] does not appear to be a big issue, the teams are discussing several options.” On the ground John Shannon told another press conference, “It’s not a great deal of concern right now, but there is a great deal of work to be done.’’ He added further detail saying, “There’s one option on the table where we just put an astronaut out there on a spacewalk, and they just tuck the fabric right back down. There are other options where they go and try to secure it down with something.’’ A third option was to have the crew use a pressure suit repair kit to sew the blanket back into place using an instrument with a rounded end that looked like a small darning needle.

Rendezvous manoeuvres began at 10:38. Following the r-bar pitch manoeuvre at 14: 37, Sturckow moved his spacecraft in for docking with PMA-2 at 15: 36. As usual, extensive pressure checks were made to ensure the seal between the two spacecraft before the hatches were opened, at 17: 04. Williams rang the station’s bell to welcome the new crew aboard ISS at 17: 20.

Following the initial greetings and safety briefing Williams transferred her Soyuz couch liner to Atlantis, while Anderson placed his couch liner in Soyuz TMA-10. Williams had been in orbit for 183 days, longer than any other female astronaut. She would now return to Earth in Atlantis, while Anderson began a four-month occupation as part of the Expedition-15 and Expedition-16 crews.

The first task for the STS-117 crew was for Archambault and Forrester to use the RMS to lift the S-3/S-4 ITS out of Atlantis’ payload bay and hand it over to the

|

Figure 90. Expedition-15: Clay Anderson poses with an American Extravehicular Mobility Unit in the Quest airlock.

|

SSRMS, which was operated by Williams. The hand-over was completed at 20: 28, and the S-3/S-4 ITS was left on the SSRMS throughout the crew’s sleep period, allowing it to warm in the unfiltered sunlight. Reilly and Olivas spent the night camped out in Quest with the airlock’s pressure reduced to purge nitrogen from their bloodstream in advance of their first EVA, planned for the following day.

The crew were up and about at 09: 08, but Reilly and Olivas were allowed to sleep in for an extra 30 minutes. After breakfast, Archambault and Forrester used the SSRMS to move the S-3/S-4 ITS towards the exposed end of the S-l ITS and held it in place. The resulting asymmetry of the new ITS being moved around caused the CMGs in the Z-l Truss to become saturated and drop off-line and the station began to drift. This had been anticipated by controllers in Houston. Archambault, Forrester, and Kotov commanded the bolts holding the S-3/S-4 ITS in place to close. As a result of the CMG dropout, the EVA began at 16: 02, approximately one hour late. Reilly and Olivas made their way to the joint between the S-l and S-3/S-4 ITS. There, they connected power cables between the two ITS elements and released the launch restraints on the S-3/S-4 ITS SAW blanket boxes and opened them. They also released the launch restraints on the S-3/S-4 radiator, rigidised the four Alpha Joint Interface Structure struts, installed one Drive Lock Assembly, and released the launch locks on the SARJ. The EVA ended at 22: 17, after 6 hours 15 minutes. Meanwhile, controllers in Houston activated the two new power channels and deployed the new radiator. Elsewhere on ISS, Williams and Anderson continued their planned hand-over tasks.

During the evening, mission managers extended the flight by 2 days and added a possible fourth, impromptu EVA, to provide time to inspect and repair the lifted thermal blanket on the port OAMS pod. Meanwhile, engineers and astronauts on the ground were trying to establish the best way to make the repair. In the regular end-of – shift press conference at MCC-Houston, Shannon informed the press and media, “We do not want to re-enter until we have done this. I don’t want to take a risk of damaging flight hardware, when we have something that looks easy to do, so it’s a pretty easy decision to make.’’ On the ground, the various repair methods were being rehearsed and subjected to testing under simulated re-entry conditions. Shannon explained that Shuttle engineers did not think that the re-entry heating on the OAMS pod would be sufficient to burn through the graphite structure beneath the lifted blanket, causing an STS-107 style break-up, but it might cause sufficient damage to require a relatively major repair, thereby throwing the Shuttle launch schedule into total disarray. The 90-minute repair would be carried out by two astronauts riding the Shuttle’s RMS. Atlantis would now land on June 21, after a 13-day flight. In orbit the day had gone well, and the crew began their sleep period. Learning from past experience, Houston commanded the new SAWs to extend in a series of small lengths. The first segment was deployed by controllers in Houston while the astronauts slept.

On June 12, the astronauts’ day began at 08: 08. At 11: 43, Sturckow, Arch – ambault, Forrester, Swanson, Olivas, Reilly, and Williams took over the task of deploying the S-3/S-4 SAWs and observing that deployment from inside ISS and Shuttle. Each SAW was deployed separately and in small stages, with regular stops to let the Sun warm the array. The first SAW was fully deployed by 12: 29, and the second by 13:58. Reilly told Houston, “We see a good deploy.” The new arrays would provide sufficient electricity to power the European and Japanese laboratory modules when they are docked to Harmony.

After dinner the Shuttle crew were given some free time before commencing preparations for the following day’s EVA. Throughout the SAW deployment, the station’s attitude had been controlled by Atlantis. As the day drew to a close, the station’s attitude control was switched back to the station’s computers. At that time all three navigation computers and all three command and control computers failed in Zvezda. The computers were built by Daimler-Benz in Germany, under an ESA contract, and one of their tasks was to activate Zvezda’s thrusters if ISS attitude manoeuvres were beyond the capabilities of the CMG. Controllers elected to let the CMGs continue to manage the station’s attitude, but Atlantis’ thrusters would be used for large manoeuvres, rather than Zvezda’s thrusters. The day ended with the pre-positioning of the MBS on the ITS and that night Forrester and Swanson camped out in Quest; both were preparations for the EVA planned for the following day. While the astronauts slept, controllers in Houston began the retraction of the remaining SAW on the P-6 ITS. They succeeded in retracting 7.5 of the 31.5 panels of the array.

The day started at the usual time and the EVA began at 14:03. Forrester mounted the RMS end-effector and was lifted to the P-6 ITS, mounted on the Z-1 Truss, while Swanson made his own way to the location. Once in place, they oversaw and assisted with the retraction of a further 5.5 panels of the 2B SAW, as commanded from inside the station. Moving back to the S-3/S-4 ITS, they removed the remaining locks holding the SARJ. Although they had originally been planned to remove the launch restraints, they left them for the third EVA. When the restraints were finally removed the joint would be free to rotate, as the SAWs tracked the Sun. They also installed a second drive-lock assembly. and that was where their problems arose. Commands sent to the second drive-lock assembly were received by the unit installed during the first EVA. Controllers in Houston confirmed that the first unit was in the “safe” condition and had to confirm that the second unit was similarly configured. The SAW retraction would continue during the following day. The EVA ended at 20: 33, after 7 hours 16 minutes. Once again Anderson spent the day completing hand-over tasks in preparation for his 5-month stay on ISS, as well as assisting Expedition-15 crewmates Yurchikhin and Kotov to transfer supplies from Atlantis to ISS. During the day mission managers confirmed that at least part of the third EVA would be spent repairing the port OAMS pod thermal blanket.

On June 14, Houston awoke the crew officially at 08: 39. In fact, they had been woken up at 07: 23, when a fire alarm sounded in Zarya. It was a false alarm set off by the loss of three Russian command and control computers, affecting the life support system and causing power outages throughout the Russian sector of the station. During the day controllers in Korolev temporarily rebooted the navigation computer and then turned it off again to continue work on the original problem. By 11 : 38, Sturckow, Lee, Archambault, Swanson, Williams, and Anderson resumed the attempt to retract the P-6 SAW. Meanwhile, Forrester, Reilly, and Olivas reviewed the procedures for their third EVA. The three of them practised the plan to staple the

|

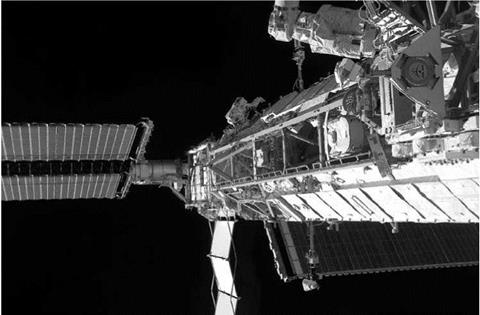

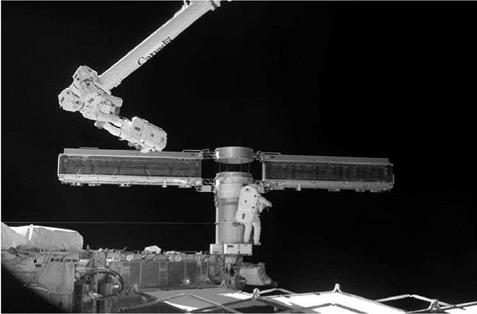

Figure 91. STS-117: Patrick Forrester works removing launch restraints from the S-4 Solar Alpha Rotary Joint.

|

|

Figure 92. STS-117: James Reilly and John Olivas work with the retracted P-6 Solar Array Wings.

|

two sections of thermal blanket on Atlantis together and pin it to an adjacent thermal tile. Sturckow told Houston, “When we first saw it, we were not too concerned. We’re still not. This is just the right thing to do, the conservative thing to do. We appreciate everyone taking a look to make sure we have the right configuration for re-entry.’’

In Moscow, Russian engineers continued to work with their American counterparts on the computer problem throughout the day. The leading theory as to the cause of the computer problem was a bad electrical power feed between the American and Russian sectors of ISS, as the computers now drew their power from the ITS. NASA’s Mike Suffredini explained, “A power line has a certain magnetic field around it, and that can affect systems near it.’’ Plans included disconnecting power cables between the two sectors of the station, rebooting the computers, and then reconnecting the power cables. If the problem recurred, the computers in the Russian sector could receive electrical power from the photovoltaic arrays on the Russian modules. Sturckow was objective, “These challenges, they come up when you bring new pieces of hardware or when computers are improved. This is to be expected. Things aren’t always going to go well.’’ Meanwhile, NASA Associate Administrator for space operations Bill Gerstenmaier was positive, telling a press conference, “This is a complex station. This failure is not easy to understand. It’s some combination between Russian systems and our systems. It’s just going to take a little bit of time to get this worked out.’’ He added, “We’re still a long way from where we would have to de-man the station.’’

NASA was at pains to point out that the station had 2 months of oxygen supply if the Russian oxygen generator could not be brought to full operation. Also the American oxygen system was nearly completely installed. Carbon dioxide removal systems were also available in both the Russian and American sectors. In Russia, the difficulties led to discussions as to whether or not to advance the next Progress launch by two weeks, to July 23, and use that launch to deliver new computer parts to the station.

Before going to bed, Williams and Anderson checked power lines and circuits connected to the new S-3/S-4 ITS that supply electricity to the Russian modules with a number of diagnostic instruments, but found nothing that could account for the computer difficulties. Meanwhile, the STS-117 crew had been instructed to power down some of Atlantis’ systems, just in case the Shuttle mission needed to be extended by a further day, to continue supplying back-up attitude control. A NASA spokesman told the press, “I expect we will have the computers back in the next several days. It’s not an urgent situation, but we clearly need to get this resolved.’’ Asked if the station would be evacuated if the computer problem persisted NASA’s Mike Suffredini insisted, “The best thing we can do is keep the crew onboard to keep working this problem until we sort it out. That is what our plan is.’’ Meanwhile, John Shannon confirmed that Atlantis would remain docked to ISS until June 20. Reilly and Olivas spent the night camped out in Quest breathing oxygen at a lowered pressure in preparation for the crew’s third EVA.

As the new day started Russian controllers disconnected the Russian modules from the new electrical power supply, returning them to the supply provided by their own photovoltaic arrays. The STS-117 crew’s wake-up call came at 08: 41, June 15,

Reilly and Olivas began preparations for their EVA straight after breakfast. The EVA began at 13:38. After collecting their tools they prepared to repair Atlantis’ thermal blanket. Olivas mounted the Shuttle’s RMS and was manoeuvred to the port OAMS pod, where he pushed the folded thermal blanket back into the correct position. Using a stapler from the Shuttle’s medical kit he fixed the offending blanket to the blanket next to it. Finally, he drove a metal pin through the blanket, securing it to the adjacent thermal tiles. The repair took the full 2 hours that had been allocated for it. As he completed the task Olivas told controllers in Houston, “Hopefully it’s going to be good, good enough.’’ Sturckow, the Shuttle’s Commander added, “He’s done an absolutely wonderful job.’’

While Olivas repaired the thermal blanket, Reilly installed a hydrogen vent in the forward face of Destiny. The vent would be used by the new American oxygen generation system. The new system would separate water into oxygen as the Russian Elektron oxygen generator did, for the crew’s life support system, and hydrogen which would be vented overboard through the new vent. With the repair and the valve installation complete, both men moved to the P-6 ITS, where they assisted in the retraction of the last 15 bays of the 2B SAW. While the retraction was commanded from inside the station, the two EVA astronauts assisted by helping to fold the SAW and ensuring that they were correctly stored in the blanket box. Finally, they secured the lid of the blanket box itself. The retraction was completed at 20:40. The EVA ended at 21: 36, after 7 hours 58 minutes.

While the Americans concentrated on their EVA, the Russians continued to work on the failed computers. All of the computers were taken off-line at 06: 00 and left off-line throughout the day. Yurchikhin and Kotov used a jumper cable to bypass a power switch, thus allowing them to get both C&C computers partially running. It was decided that the one processor in each computer that did not re-boot would be replaced using spares to be delivered by the next Progress. The computers, which only required one processor each to perform their role on ISS, were left running overnight. A telemetry downlink over a Russian ground station allowed controllers in Korolev to monitor the computers’ performance over the test period. NASA spokeswoman Lynette Madison told the press, “They’re up and operational and this is good news for all.’’ Mike Suffredini made a similar comment, “We feel like the computers are stable and back to normal.’’

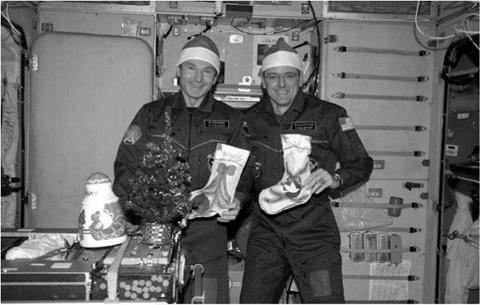

Whilst the two crews were asleep, Sunita Williams became the most experienced female astronaut in history. At 01: 47, June 16, she passed the female endurance record of 188 days 4 hours set by her NASA colleague, Shannon Lucid. Later in the day Williams remarked:

“I feel like a lot of this was just sort of being in the right place at the right time. It just sort of happened. It’s just an honour to be up here. Even when the station has little problems, it’s just a beautiful, wonderful place to live. I’m just happy to be part of history that provides a steppingstone for the next generation of explorers and women to come up here and do that. To me, it’s no big deal.’’

Williams admitted:

“My biggest desire is to go for a walk on the beach. I grew up near the beach in New England, and I love going to the beach.”

Lucid, who had worked in MCC-Houston during Williams’ flight, told a press conference, “She’s done an absolutely wonderful job. I think it’s really great because it shows the space programme is getting more mature when you have more and more people stay in space for longer periods of time.’’ She added, “I said [to Williams], ‘Enjoy your last few days because all too soon you will be back to bills, dirty dishes and laundry’.’’

The Shuttle crew’s wake-up call came at 08:38, June 16. They spent the day transferring supplies from Atlantis to ISS and preparing for the flight’s fourth EVA. Yurchikhin and Kotov used a second external cable to redirect the power supply, allowing them to bring the final two computer processors on-line. With Zvezda’s computers performing well, controllers in Korolev began assigning them some of their usual control tasks. The computers were now talking to the equivalent C&C computers in the American sector of ISS, something they had not been doing for the past 3 days. By this time most people did not believe the S-3/S-4 power supply had caused the computer problem. Flight Director Holly Ridings stated, ‘‘In the last 24 hours, we’ve had a lot of successes.’’ ISS programme manager Mike Suffredini, summed up his feelings succinctly, ‘‘Spaceflight is a challenging business and these are the things you occasionally have to deal with. We can all go home and not do it, or we can choose to explore. We choose to explore.’’ He told the media, ‘‘We’re having a great day on orbit.’’ As the day continued NASA suggested that Atlantis would land on June 21. On hearing the news, Sturckow replied, ‘‘That’s great news.’’

June 17 began at 07: 38. Following breakfast everyone began preparations for the final EVA. Forrester and Swanson had spent the night camping out in Quest. Their EMUs were transferred to internal battery power, commencing the EVA at 12: 25. Kotov shadowed Reilly as intravehicular crew member, in preparation for his assuming that role during an up-coming Expedition-15 Stage EVA. Having collected their tools, Forrester and Swanson set to work. Their first task was to retrieve a camera and its stand from a mounting on the exterior of Quest and move it to the S-3 ITS. While on the S-3/S-4 ITS, they confirmed the Drive Lock Assembly-2 configuration and then removed the final six SARJ launch restraints, leaving the SAWs free to rotate and track the Sun as ISS orbited Earth. Reilly told them, ‘‘Great job, Guys,’’ Swanson replied, ‘‘That’s what we came here to do.’’

Still on the ITS, they moved the temporary stops installed on the MBS rails, leaving the MBS free to travel along its rails on the new length of ITS. They also removed additional equipment that had held the S-3/S-4 ITS in the Shuttle’s payload bay. The task was the final one scheduled for STS-117 and was completed by 16: 17. The remaining activities were ‘‘get-ahead’’ tasks. First they installed a computer network cable on the outside of Unity and then moved to open the newly installed hydrogen vent valve on Destiny. Finally, they tethered two debris shield panels on Zvezda. The EVA ended at 18: 54, after 6 hours 29 minutes. Inside, the Russian computers had been returned to controlling the station’s systems, and even the

Elektron oxygen generator was powered on, but not configured to produce oxygen. The computers remained stable.

During an evening press conference, Anderson was asked how he was adapting to life on ISS. He replied, “I think I’m hanging in there. It kind of reminds me of my first swimming lesson. I just got tossed in the water and told to survive.’’ Questioned on the subject of Zvezda’s computers, Yurchikhin remarked cautiously, “We’re slowly moving back toward a normal mode of operations.’’

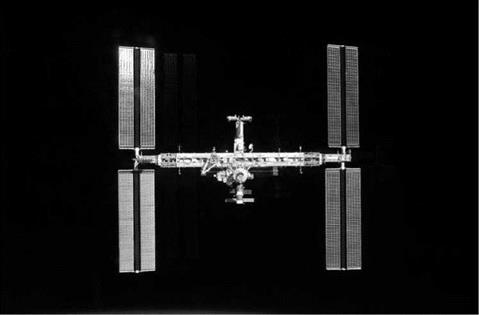

While the two crews slept, American controllers in Houston activated the SARJ on the S-3/S-4 ITS and tested its rotation. At 20:00, the SARJ was placed in autotrack mode. The ISS now had a new symmetrical shape, with a pair of SAWs at either end of the ITS and the P-6 SAWs fully retracted, although the P-6 ITS was still attached to the Z-l Truss, with one of its huge radiators still deployed.

The final day of docked Shuttle operations began with the crew rising early, at 07: 08, June 18. The crew of Atlantis had the morning off after the hectic pace of the past few days. They completed the final transfer of equipment to Atlantis during the afternoon. At 10: 28, the Shuttle’s thrusters were used to manoeuvre the station into the correct position for a combined potable water and waste water dump and then manoeuvre it back to the original position. Once the combination was stable, after the second Shuttle manoeuvre, at 10: 34, attitude control was passed to the Russian terminal computer. The computer activated the thrusters on the Russian modules to maintain the station’s attitude. At 12: 09, attitude control was handed back to the American computers and the CMGs mounted in the Z-l Truss. The test was summed up by NASA’s Phil Engelhauf, “There was absolutely nothing anomalous out of the testing. Everything performed exactly as it should have.’’ Only after the test of the Russian computers was successfully completed did NASA managers confirm that Atlantis would undock at 10: 42, June 20.

After saying their goodbyes to the Expedition-15 crew, Sturckow led his crew back to Atlantis, securing the hatches between the two vehicles for the final time at 18: 51. Sunita Williams was included in that crew, returning to Earth after almost 6 months in space. Williams remarked, “It’s sad to say goodbye, but it means that progress is being made.’’ Yurchikhin told controllers, “We had a really great time with Suni up here.’’ Her place on the Expedition-15 crew had been taken by Clayton Anderson who remarked, “I hope I can carry on, and do half as well as she did.’’

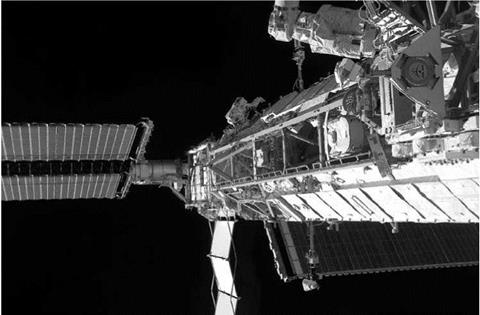

Atlantis undocked at 10: 42, June 20, with Archambault at the controls. The Pilot manoeuvred the orbiter around the station so that the crew could complete a photographic and video survey, before performing the separation manoeuvre. Sturckow told the Expedition-15 crew, “Have a great rest of your mission.’’ Yurchikhin replied, “Godspeed, and thanks for everything.’’

Following the separation burn, the crew used the RMS-mounted OBSS to carry out further scans of the Shuttle’s nosecap and wing leading edges. The images were down-linked to Houston before the astronauts began their evening meal and sleep period. Following an early morning start, the crew spent what should have been their last full day in space carrying out all of the routine preparations for re-entry. These included a test of the aerodynamic surface and a test-firing of each of the Shuttle’s manoeuvring thrusters. While the crew prepared to come home, the weather over

|

Figure 93. STS-117: image shows the protruding corner of a thermal blanket on the orbiter’s OAMS pod.

|

|

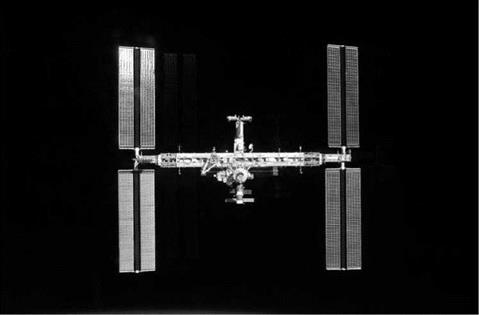

Figure 94. STS-117 departs ISS. Note the station’s new symmetry and the retracted P-6 Solar Array Wings.

|

Florida threatened the plans for returning to that location. Sturckow told controllers in Houston, “Get us some good weather for Thursday, if you can. It doesn’t have to be good, just good enough.’’

On June 21, the final preparations were made. Following breakfast the Ku-band antenna was stowed, and the payload bay doors were closed at 10:05. Retrofire was planned for 12: 50. That attempt was cancelled due to bad weather. The day’s final landing opportunity demanded retrofire be completed at 14: 25, but that attempt was cancelled at 13:38, as the weather in Florida showed no signs of clearing. Sturckow was informed, “The rain showers and cloud ceilings will keep us from making it into Florida today. We are going to try again tomorrow.’’

Atlantis’ payload bay doors were re-opened and a manoeuvre was performed to adjust the orbit to support the five available landing attempts (two at KSC in Florida and three at Edwards Air Force Base in California) on June 22. The crew spent the extra day and night in orbit, before beginning re-entry preparations again.

On June 22, Sturckow was informed, “Our mindset is we’re going to land you somewhere safely today.’’ The payload bay doors were closed at 09: 32. The first attempt to land in Florida was cancelled. Landing finally occurred on the dry lakebed at Edwards Air Force Base, California, at 16: 49. The flight of STS-117 had lasted 13 days 20 hours 11 minutes. Williams had been in space for 195 days. At the postlanding press conference NASA Associate Administrator for space operations Bill Gerstenmaier told the media, “My hat’s off to the team that really pulled off an awesome mission.’’ Returning Atlantis to Florida on the back of a Boeing 747, NASA carrier aircraft would require a week’s work and cost $900,000.

In the weeks following Atlantis’ recovery, pressure suit engineers discovered a small cut in the outside layer of one of Curbeam’s EMU gloves. As a result, NASA introduced a new rule that required astronauts on an EVA to examine their gloves approximately every 60 minutes while they were in a vacuum.