WHAT NOW?

The success of Apollo 8 presented Soviet space planners with a double problem: how should they modify their programme in the light of America’s success; and how should these changes be presented to the world? A joint government-party meeting was held on 8th January, a week into the new year. Feelings among ministers and officials verged on panic and they must now have got an inkling as to how the Americans must have felt after the early Soviet successes. Thus, a new joint resolution of the party and the Council of Ministers, # 19-10, was passed on 8th January 1969. They agreed, in a bundle of decisions:

• The L-1 programme would continue, although the majority took the view that there would be little point in conducting a mission now clearly inferior to the achievement of Apollo 8.

• The programme for the N-1 would also continue, although it was apparent that it would fall short of what the Americans planned to achieve under Apollo, quite apart from running several years behind. Once successfully tested, the N-1 could be reconfigured for a mission that would overtake Apollo. Manned flights to Mars in the late 1970s were mooted – ironically the original mission for the N-1.

• Unmanned probes to the moon, Mars and Venus would be accelerated. The public presentation of the Soviet space programme would emphasize these goals.

• Ways would be explored of accelerating a manned space station programme, Vladimir Chelomei’s Almaz project.

Although they now realized that their chances of beating the Americans to the moon had now sharply diminished, there was no support for the idea of abandoning the

moon programme. Although this was nowhere written down, there was probably the lingering hope that America’s rapid progress might hit some delays. But, in their hearts they must have known that basing their progress on the difficulties of others was not a sound basis for planning. This was not how the Soviet space programme worked in its golden years.

Now came a new generation of unmanned Russian moon probes, following the first generation (1958-60, Ye-1 to Ye-5) and the second (1963-8, Ye-6 and Ye-7). These were substantially larger and designed to be launched on the Proton rocket and called the Ye-8 series, of which the programme chief designer was Oleg Ivanovski. There were three variants:

Ye-8 Lunar rover (Lunokhod) (originally the L-2 programme)

Ye-8-5 Lunar sample return

Ye-8LS Lunar orbiter

Although finally approved in January 1969, these missions had actually been in preparation for some time in the Lavochkin design bureau. Available first was the moon rover, or Lunokhod, the Russian word for ‘moonwalker’, and it was nearly ready to go. Although the Soviet Union portrayed the Lunokhod series as a cheap, safe, alternative to Apollo and although Lunokhods followed the American landings, the original purpose of the series was to precede and pave the way for Russian manned landings. Ideas of lunar rovers were by no means new and dated, as noticed earlier, to the 1950s. Design work had proceeded throughout the 1960s. The moon rover was intended to test the surface of the intended site for the first manned landing; later versions would carry cosmonauts across the moon. Indeed, they were endorsed in science fiction. The story of Alexander Kazanstev’s Lunnaya doroga (Lunar road) was how a Soviet rover rescued an American in peril on the moon [1].

At the other extreme, the lunar sample return mission had been put together at astonishingly short notice. By early 1967, the design of the Ye-8 lunar rover had been more of less finished. The Lavochkin design bureau figured out that it might be possible to convert the upper age, instead of carrying a lunar rover, to carry a sample return spacecraft. The lower stage, the KT, required almost no modification and could be left as it was. Now on top sat the cylindrical instrumentation unit, the spherical return capsule atop it in turn and underneath an ascent stage. A long robot arm, not unlike a dentist’s drill, swung out from the descent stage and swivelled round into a small hatch in the return cabin. The moonscooper’s height was 3.96 m, the weight 1,880 kg. The plan was for a four-day coast to the moon, the upper stage lifting off from the moon for the return flight to Earth. The mission was proposed as insurance against the danger of America getting a man on the moon first. At least with the sample return mission, Russia could at least get moon samples back first. The sample return proposal, called the Ye-8-5, was rapidly approved and construction of the first spacecraft began in 1968.

Sample return missions were designed to have the simplest possible return trajectories. Originally, it was expected that a returning spacecraft would have to adjust its course as it returned to Earth. In the Institute of Applied Mathematics,

Dmitri Okhotsimsky had calculated that there was a narrow range of paths from the moon to the Earth where, if the returning vehicle achieved the precise velocity required, no course corrections would be required on the flightpath back and the cabin could return to the right place in the Soviet Union. This was called a ‘passive return trajectory’. Such a trajectory was only possible from a limited number of fairly precise landing cones between 56°E and 62°E, and these were calculated following Luna 14’s mapping of the lunar gravitational field. Returning from one of these cones meant that Luna could just blast off directly for Earth and there was no need for a pitch-over during the ascent, nor for a mid-course correction. If it reached a certain speed at a certain point, then it would fall into the moon-Earth gravitational field. Gravity would do the rest and the cabin would fall back to Earth. On the other hand, the passive return trajectory limited the range of possible landing spots on the moon, meant that the actual landing spot must be known with extreme precision (±10 km), the take-off must be at exactly the right second and the engine must achieve exactly the right velocity, nothing more or less [2]. Sample return missions had to be timetabled backward according to the daytime recovery zone in Kazakhstan and the need to have the returning cabin in line of sight with northern hemisphere ground tracking during its flight back to Earth. Thus, the landing time on Earth determined the landing point and place on the moon, and this in turn determined when the probe would be launched from Earth in the first place.

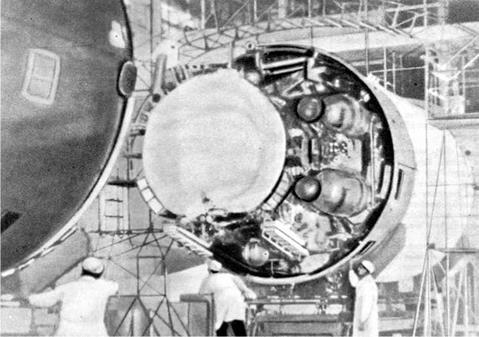

The Ye-8 series all used common components and a similar structure. The base was 4 m wide, consisting of four spherical fuel tanks, four cylindrical fuel tanks, nozzles, thrusters and landing legs. Atop the structure rested either a sample return capsule, a lunar rover or an instrument cabin for lunar orbit studies. By spring 1969, the time of the government and party resolution, Lavochkin had managed to build one complete rover and no fewer than five Ye-8-5s and have them ready for launch. In the case of the ascent stage, a small spherical cabin was designed, equipped with antenna, parachute, radio transmittter, battery, ablative heatshield and container for moonrock.

The first Lunokhod was prepared for launch on 23rd February 1969 and was aimed at the bay-shaped crater, Le Monnier, in the Sea of Serenity on the eastern edge of the moon [3]. The timing of the Lunokhod missions was affected by the need to land in sufficient light to re-charge the rover’s batteries before the onset of lunar night. It had been arranged that when it drove down onto the lunar surface, a portable tape recorder would play the Soviet national anthem to announce its arrival. Proton failed when, 50 sec into the mission, excessive vibration tore off the shroud and the whole rocket exploded 2 sec later, the remains coming down 15 km from the launch site. For months, the military tried to find the nuclear isotope that should have powered the rover across the surface of the moon. Apparently, some local troops downrange on sentry duty found it and, clearly insufficiently briefed about the dangers of polonium radiation, used it to keep their patrol’s hut warm for the rest of that exceptionally cold winter. Parts of the lunar rover were found – wheels and part of the undercarriage – and were remarkably undamaged. Even the portable tape recorder was found, playing the Soviet national anthem on the steppe, not Le Monnier bay as had been hoped [4].

|

Lunokhod on top of Proton |