With ever more of their training concentrated at Cape Canaveral, NASA eventually relocated the astronauts to crew quarters on the west side of the Cape, several miles from the Redstone launch complex. As at Langley, the quarters were nothing special; they were situated in an old concrete block Air Force hangar known as Hangar S, in which the Martin Company people had prepared the Vanguard rockets for launch. As with all such hangars at the Cape, its floor plan was very basic, having a two-story high-bay area in the center between two large sliding doors, and regular access doors at each end. Offices or stage rooms were located on both sides of each floor.

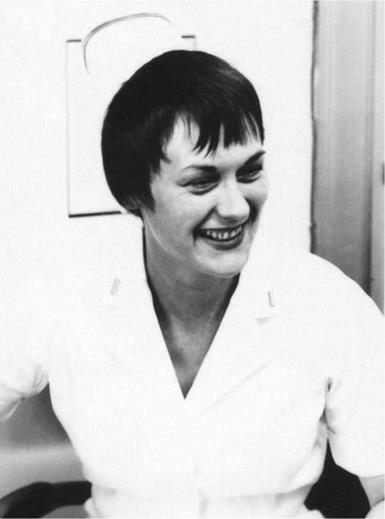

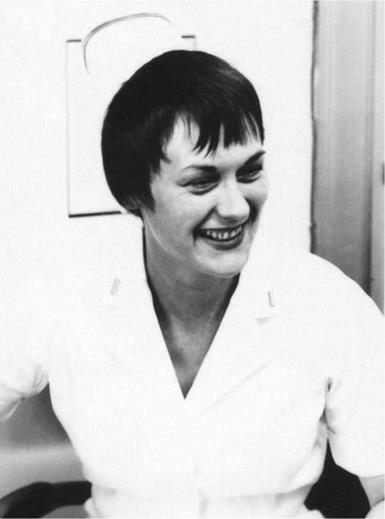

Dr. William Douglas, the astronauts’ personal physician, was aided by a levelheaded young Air Force nurse named Delores O’Hara, who would not only tend to any illnesses or injuries they or their families suffered, but eventually become a true and sympathetic confidante to the men and their wives. Dee O’Hara, as she is better known, was an Idaho-born 2nd lieutenant in the Air Force Nurse Corps serving at the nearby Patrick Air Force Base Hospital, when her commanding officer asked if she would like to be the nurse assigned to NASA’s Mercury astronauts.

When the news leaked out of her assignment, the press began to hail Dee as the nation’s “Space Nurse” and “Astronaut Nurse,” but she insisted that the only proper designation was aerospace nurse.

|

The astronauts’ nurse, Dee O’Hara. (Photo: NASA)

|

|

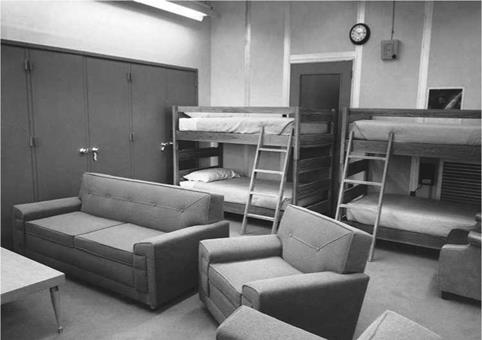

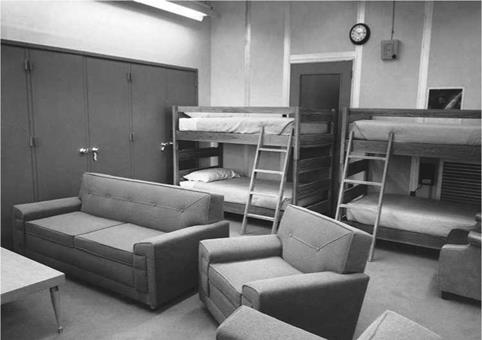

The rather austere astronauts’ quarters in Hangar S. (Photo: NASA)

|

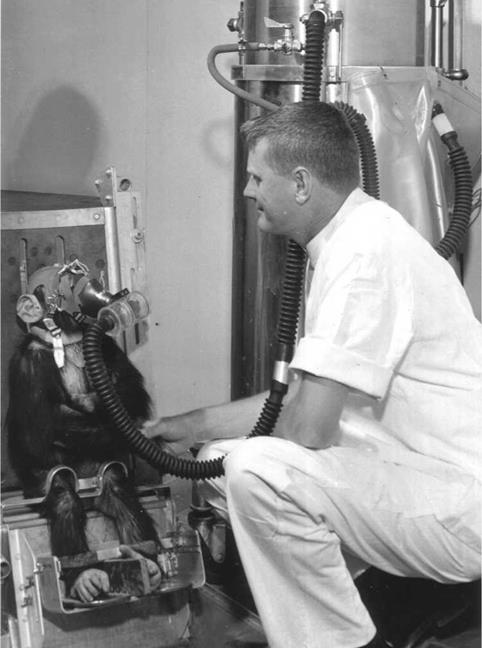

One of the first major responsibilities assigned to young Dee O’Hara was to help establish what was referred to as the Aeromed lab in Hangar S.

“I always felt the Mercury program was launched from Hangar S because we were all crammed in this one little hangar. The suit rooms were there, the capsule was there – everything existed in Hangar S. And so I set up the Aeromed lab. It was a long string of rooms. It was very narrow. We had a hallway, the rooms, and then it overlooked the floor of the hangar, if you will. I had a lab area, an exam room area, then there was my little office. Then we had a large room, a carpeted room where the suits were, the suit couch was there, and all of the suit checkouts were done there. And then you went to the next room, which was kind of set up as a conference room for them, and then past that was a little lounge area with a La-Z-Boy chair… it was considered crew quarters if you will. Primitive, but it was considered crew quarters. And in the next room, and these are all very small rooms, were bunk beds for if the astronauts stayed there. Most of them stayed in motels in Cocoa Beach, but if they were training late, or working late in the capsule, they could at least bunk there and sleep the night, and not have to drive. Because I think it was like nineteen miles or so back into Cocoa Beach. Granted, that’s not a long drive, but you’re out in the middle of nowhere; I mean of course it’s all built up now, but back then it was not. I think the first motel bar was the Polaris Lounge or something like that, and so it was kind of distant to the Holiday Inn where most of them stayed.” [24]

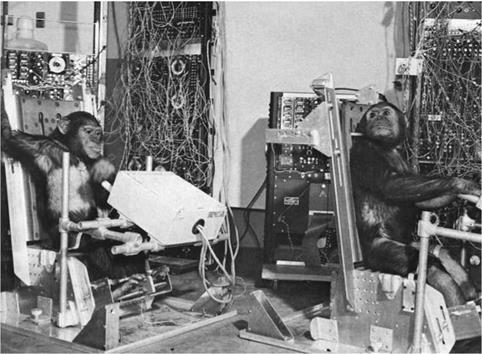

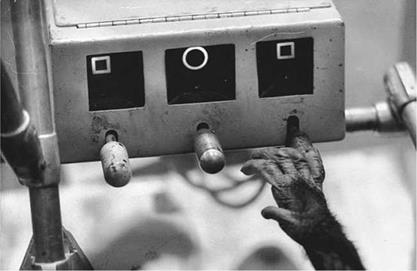

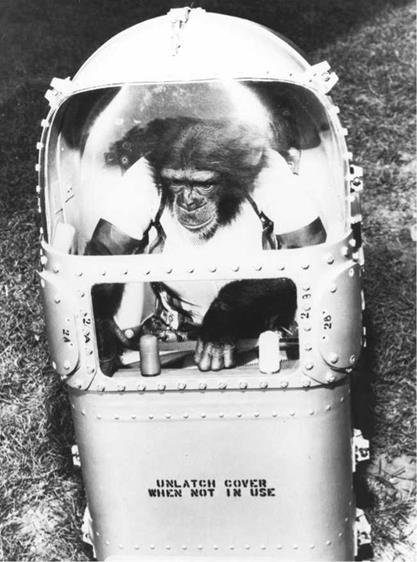

Despite their fame, the pioneering years of space flight were often rather less than glamorous for the Mercury astronauts. Shepard recalls the early ignominy of living alongside a colony of space-trained primates. Back then, the astronauts knew that they were being forced to play second fiddle to the chimpanzees. “The crew quarters at Hangar S were Spartan, austere, nondescript, and totally uncomfortable,” Shepard wrote. “Our sleeping quarters could be reached only by going down a long, poorly lit hallway, an unpleasant walk during which we were assailed by the hoots, screeches and screams of a small colony of apes housed out back. In the end, we decided the humiliation of stepping aside for a monkey was bad enough. We certainly didn’t have to live with the howling dung-flingers.” As Dee O’Hara suggested, most of the astronauts moved into a Holiday Inn at Cocoa Beach [25].

Apart from their overall work on the Mercury program, each of the astronauts was handed an assignment which would become his specialized field. Each then shared vital information on his subject with the others. Scott Carpenter was given capsule communications and navigation; Gordon Cooper, engineering developments to adapt the Redstone missile to launch the manned capsule on suborbital flights; John Glenn was to monitor the layout of the capsule interior, as well as its instrumentation and controls; Gus Grissom was assigned the capsule’s automatic pilot; Wally Schirra got the capsule’s environmental control system; Deke Slayton looked ahead to mating the spacecraft with the Atlas booster for orbital flights; and Alan Shepard was given responsibility for the capsule recovery and rescue program.

McDonnell’s Pad Leader, Guenter Wendt, was hard at work preparing for the first manned flight, but concerns were still cropping up that no one had considered, such as an effective means of evacuating an astronaut from a spacecraft in peril whilst on the launch pad.

“As we moved closer to our manned launches, it came to our attention that we had no means of egress for the astronaut if an emergency occurred while the launch tower was parked several hundred feet away. I think it was Bob Munger who came up with the idea of using the ‘cherry picker.’ This was a yellow, crane-like rig on a long flatbed truck. It was operated by remote control. Its long boom could remain in position close to the spacecraft until right before the launch. In an emergency such as a fire on the pad, the astronaut could open the hatch and climb into the metal cage on the boom’s end. We would then swing him out of harm’s way. It was a bit crude, but it did the job.” [26] “MY NAME, JOSE JIMENEZ”

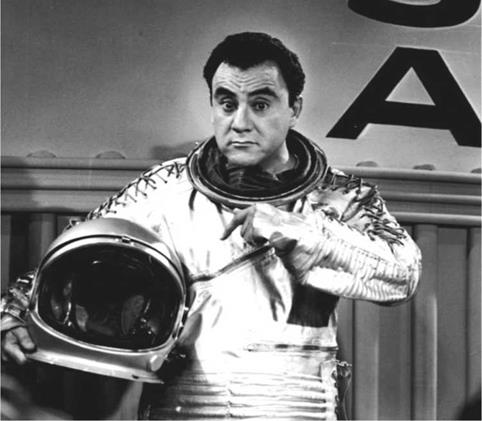

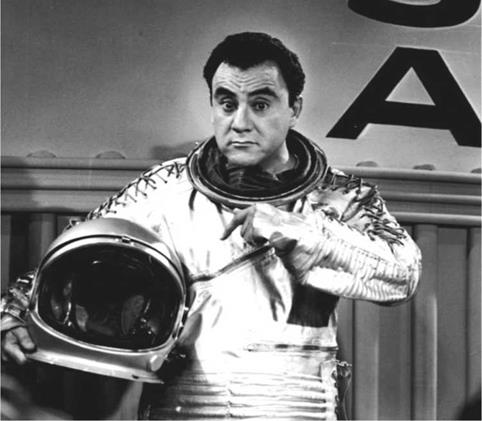

If there was one person in his life that Alan Shepard truly came to admire after he was selected as an astronaut, it was a short, stocky fellow who was born in Quincy, Massachusetts with the tongue-twisted name of William Szathmary. Adopting the stage name of Bill Dana, the comedian became an instant hit with the astronauts, and in particular Shepard, due to his hilarious routines centered on a bumbling, nervous astronaut character named “Jose Jimenez.”

Shepard could recite many of Dana’s routines off by heart, and would often slip into the Jimenez character during training in order to relieve any pent-up anxieties. The astronauts soon got to know Dana well, and embraced him as one of their own. With their enthusiastic blessing he was forever endowed with the title of the “eighth astronaut.”

|

Comedian Bill Dana as Jose Jimenez, the nervous astronaut. (Photo: Bill Dana)

|

Shepard once spoke about the origin of his close affinity with the much-loved comedian. “There was this TV program and I was crazy about it. It was so close to the way that we see things when we’re in a good mood. In short, I liked him so much I recorded it on tape, then I took the tape to Cape Canaveral and during the Ranger launching, at a moment when they stopped the countdown because something was wrong, I put the tape on at full volume there in the control room. Sometimes we like to have a little fun too. It releases the tension.”

As Wally Schirra recalled, “Dana was doing a one-night stand in Cocoa Beach near Cape Canaveral, and Al Shepard and I were in the audience. When Dana asked for a straight man, Al volunteered. Then I did, too. What we really liked about Dana is that he made himself the butt of his jokes. Like Bob Hope, also a dear friend of the astronauts, he did not get laughs at the expense of someone else.” [27]

One skit which Shepard was especially fond of centered on an interview between a reporter (played straight by Don Hickley) and Jose Jimenez, chief astronaut of the Interplanetary Forces of the U. S.A. In part, the routine goes like this:

DH: The gentleman you’re about to meet is the most important man in any of our

lives. He’s the United States’ officer who has been sent into outer space. I’m referring to the chief astronaut with the United States Interplanetary Expeditionary Force, and here he is now. How do you do sir. May we have your name?

JJ: My name, Jose Jimenez.

DH: And you’re the chief astronaut with the United States Interplanetary

Expeditionary Force?

JJ: I am the chief astronaut, with the United States… Interplanetary… My name

Jose Jimenez.

DH: Mr. Jimenez could you tell us a little about your space suit?

JJ: Yes, it’s very uncomfortable.

DH: How much did the space suit cost?

JJ: That space suit cost 18,000 dollars.

DH: 18,000 dollars? That seems rather expensive.

JJ: Well it has two pair of pants… so that’s only 9,000 dollars apiece.

DH: I’ve been noticing this, Mr. Jimenez. What is this called? A crash helmet?

JJ: Oh, I hope not.

DH: I want to ask you: What is the most important thing in rocket travel?

JJ: To me, the most important thing in the rocket travel is the blast off.

DH: The blast off?

JJ: I always take a blast before I take off (pause) otherwise I wouldn’t get in that thing.

DH: And I just wonder what you’ll do to entertain yourself during those long, lonely,

solitary, hours when you’re all by yourself?

JJ: Well, I plan to cry a lot.

DH: I just wonder if there are a few words that you’d like to say to the people of the

United States?

JJ: Yes, there are a few words that I’d like to say…

DH: Please go ahead.

JJ: People of the United States of America… please don’t let them do this to me!

While there was often a mischievous, even impish side to Alan Shepard, he took the flying aspect of his new vocation very seriously. Those who knew him best often recall there were two sides to the man: there was Al who loved a good practical joke, and then there was the serious, pragmatic Commander Shepard who could cut people down with a withering stare when they did not meet the high expectations which he demanded in regard to their job functions. If he was in the latter mood, people only approached him with great trepidation.

“Al was the most complex of the original astronauts,” Gordon Cooper revealed in his memoirs. “He seemed to have two distinct personalities: one the charming and beguiling jokester who introduced Jose Jimenez – comedian Bill Dana’s popular alter ego – and his ‘Please don’t send me’ astronaut act into our everyday lives; and the other which came out when the chips were down and was so competitive as to be ruthless. We all knew to watch our backs when that Al was around.” [28]