The Engine

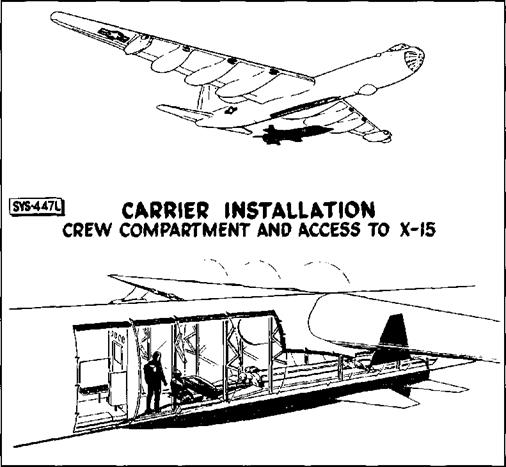

Those concerned with the success of the X-15 had to monitor the development of the aircraft itself, the XLR99 rocket engine, the auxiliary power units, an inertial system, a tracking range, a pressure suit, and an ejection seat. They had to make arrangements for support and B-36 carrier aircraft, ground equipment, the selection of pilots, and the development of simulators for pilot training. It was necessary to secure time on centrifuges, in wind tunnels, and on sled tracks. The ball-nose had to be developed, studies made of the compatibility of the X-15 and the carrier aircraft, and other studies on the possibility of extending the X-15 program beyond the goals originally contemplated. In addition to such tasks, funds to cover ever increasing costs had to be secured if the project were to have any chance of ultimate success, and at certain stages the effects of possibly harmful publicity had to be considered. With such multiplicity of tasks, it could be expected that several serious problems would arise; not surprisingly, probably the most serious arose during the development of the XLR99.

Finding a suitable engine for the X-15 had been somewhat problematic from the earliest stages of the project, when the WADC Power Plant Laboratory had pointed out that the lack of an acceptable rocket engine was the major shortcoming of the NACA’s original proposal. The laboratory did not believe that any available engine was entirely suitable for the X-15 and held that no matter what engine was accepted, a considerable amount of development work could be anticipated. Most of the possible engines were either too small or would need too long a development period. In spite of these reservations, the laboratory listed a number of engines worth considering and drew up a statement of the requirements for an engine that would be suitable for the proposed X-15 design. The laboratory also made clear its stand that the government should “… accept responsibility for development of the selected engine and… provide this engine to the airplane contractor as Government Furnished Equipment.”2′

The primary requirement for an X-15 engine, as outlined in 1954, was that it be capable of operating safely under all conditions. Service life would not have to be as long as for a production engine, but engineers hoped that the selected engine would not depart too far from production standards. The same attitude was taken toward reliability; the engine need not be as reliable as a production article, but it should approach such reliability as nearly as possible. There could be no altitude limitations for starting

or operating the engine, and the power plant would have to be entirely safe during start, operation, and shutdown, no matter what the altitude. The laboratory made it quite clear that a variable thrust engine capable of repeated restarts was essential.

The engine ultimately selected was not one of the four originally presented as possibilities by the Power Plant Laboratory. The ultimate selection was foreshadowed, however, in discussions with Reaction Motors concerning the XLR10, during which attention was drawn to what was termed "… a larger version of [the] Viking engine [XLR30].” In light of subsequent events, it was interesting to note that the laboratory thought26 the XLR30 could be developed into a suitable X-15 engine for less than $5,000,000 …” and with “ … approximately two years’ work.”27

After North American had been selected as the winner of the X-15 competition, plans were instituted to procure the modified XLR30 engine that had been incorporated in the winning design. Late in October, Reaction Motors was notified that North American had won the X-15 competition and

that the winner had based his proposals upon the XLR30 engine.28

On 1 December 1955 a $1,000,000 letter contract was initiated with Reaction Motors for the development of a rocket engine for the X-15.-"’ Soon afterwards, a controversy developed over the assignment of cognizance for the development of the engine. It began with a letter from Rear Adm. W. A. Schoech of the Bureau of Aeronautics. Adm. Schoech contended that since the XLR30-RM-2 rocket engine was the basis for the X-15 power plant, and the BuAer had already devoted three years to the development of that engine, it would be logical to assign the responsibility for further development to the Navy. The admiral felt that retention of the program by the BuAer would expedite development, especially as the Navy could direct the development toward an X-15 engine by making specification changes rather than by negotiating a new contract.30

The Navy’s bid for control of the engine development was rejected on 3 January 1956 on the grounds that the management responsibility should be vested in a single agency, that conflict of interest might generate delay,

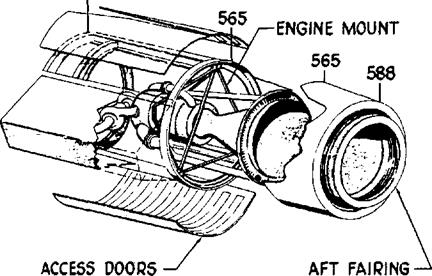

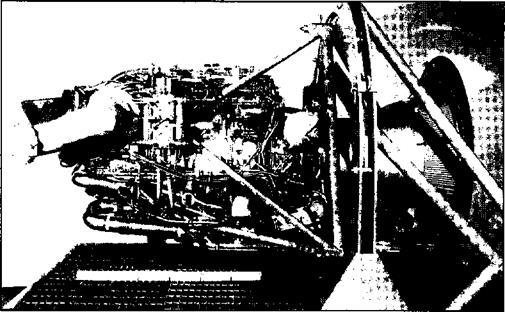

The XLR99 was an extremely compact engine, considering it was able to produce over 57,000 pounds – thrust. This was the first throttleable and restartable man-rated rocket engine. Many of the lessons-learned from this engine were incorporated into the Space Shuttle Main Engine developed 20 years later. (NASA)

The XLR99 was an extremely compact engine, considering it was able to produce over 57,000 pounds – thrust. This was the first throttleable and restartable man-rated rocket engine. Many of the lessons-learned from this engine were incorporated into the Space Shuttle Main Engine developed 20 years later. (NASA)

and that BuAer was underestimating the time and effort necessary to make the XLR30 a satisfactory engine for piloted flight.

The Final Reaction Motors technical proposal was received by the Power Plant Laboratory on 24 January, with the cost proposal following on 8 February.31 The cover letter from Reaction Motors promised delivery of the First complete system “… within thirty (30) months after we are authorized to proceed.”32 Reaction Motors also estimated that the entire cost of the program would total $10,480,718.33 On 21 February the new engine was designated XLR99-RM-1.34

The 1956 industry conference heard two papers on the proposed engine and propulsion system for the X-15. The XLR99-RM-1 would be able to vary its thrust from 19,200 to 57,200 pounds at 40,000 feet using anhydrous ammonia and liquid oxygen (LOX)35 as propellants. Specific impulse was to vary from a minimum of 256 seconds to a maximum of 276 seconds. The engine was to Fit into a space 71.7 inches long and 43.2 inches in diameter, have a dry weight of 618 pounds, and a wet weight of 748 pounds. A single thrust chamber was supplied by a

hydrogen-peroxide-driven turbopump, with the turbopump’s exhaust being recovered in the thrust chamber. Thrust control was by regulation of the turbopump speed.36

The use of ammonia as a propellant presented some potential problems; in addition to being toxic in high concentrations, ammonia is also corrosive to all copper-based metals. There were discussions early in the program between the Air Force, Reaction Motors, and the Lewis Research Center37 about the possibility of switching to a hydrocarbon fuel. It was finally concluded that changing fuel would add six months to the development schedule; it would be easier to learn to live with the ammonia.38 There is no documentation that the ammonia ultimately presented any significant problems to the program.

The decision to control thrust by regulating the speed of the turbopump was made because the other possibilities (regulation by measurement of the pressure in the thrust chamber or of the pressure of the discharge) would cause the turbopump to speed up as pressure dropped. As the most likely cause of pressure drop would be cavitation in the propellant system, an increase in turbopump

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

speed would aggravate rather than correct the situation. Reaction Motors had also decided that varying the injection area was too complicated a method for attaining a variable thrust engine and had chosen to vary the injection pressure instead.

The regenerative cooling of the thrust chamber created another problem since the variable fuel flow of a throttleable engine meant that the system’s cooling capacity would also vary and that adequate cooling throughout the engine’s operating range would produce excessive cooling under some conditions. Engine compartment temperatures also had to be given more consideration than in previous rocket engine designs because of the higher radiant heat transfer from the structure of the X-15. Reaction Motors’ spokesman at the 1956 industry conference concluded that the development of the XLR99 was going to be a difficult task. Subsequent events were certainly to prove the validity of that prediction.

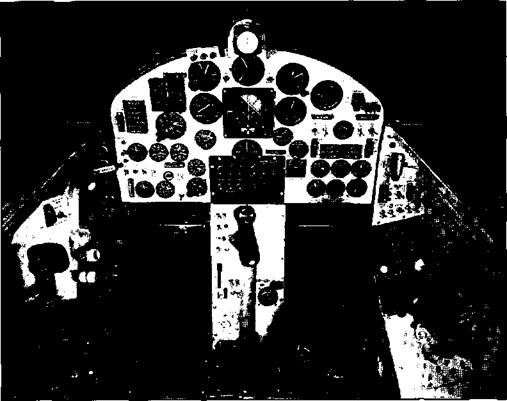

A second paper dealt with engine and accessory installation, the location of the propellant system components, and the engine controls and instruments. The main propellant tanks were to contain the LOX, ammonia, and the hydrogen peroxide. The LOX tank,

with a capacity of approximately 1,000 gallons, was located just ahead of the aircraft’s center of gravity; the 1,400 gallon ammonia tank was just aft of the same point. A center core tube within the LOX tank would provide a location for a supply of helium under a pressure of 3,600 psi. Helium was used to pressurize both the LOX and ammonia tanks. A 75-gallon hydrogen peroxide tank behind the ammonia tank provided the monopropellant for the turbopump.

Provision was also made to top-off the LOX tank from a supply carried aboard the carrier aircraft; this was considered to be beneficial in two ways. The LOX supply in the carrier aircraft could be kept cooler than the oxygen already aboard the X-15, and the added LOX would permit cooling of the X-15’s own supply by boil-off, without reduction of the quantity available for flight. The ammonia tank was not to be provided with a top-off arrangement, as the slight increase in fuel temperature during flight was not considered significant enough to justify the complications such a system would have entailed.

On 10 July 1957, Reaction Motors advised the Air Force that an engine satisfying the contract specifications could not be developed unless the government agreed to a nine-

The XLR99 on a maintenance stand. The engine used ammonia (NH3) as fuel and liquid oxygen (LOX) as the oxidizer. The XLR99 required a separate propellant, hydrogen peroxide, to drive its high-speed turbopump—the Space Shuttle Main Engine uses the propellant itself (LH2 or L02, as appropriate) to drive the turbopumps. (AFFTC via the Tony Landis Collection)

month schedule extension and a cost increase from $15,000,000 to $21,800,000. At the same time, Reaction Motors indicated that it could provide an engine that met the performance specification within the established schedule if permitted to increase the weight from 618 pounds to 836 pounds. The company estimated that this overweight engine could be provided for $17,100,000. The Air Force elected to pursue the heavier engine since it would be available sooner and have less impact on the overall X-l5 program.

Those who hoped that the overall performance of the X-l5 would be maintained were encouraged by a report that the turbopump was more efficient than anticipated and would allow a 197 pound reduction in the amount of hydrogen peroxide necessary for its operation. This decrease, a lighter than expected airframe, and the increase in launch speeds and altitudes provided by a recent substitution of a B-52 as the carrier aircraft, offered some hope that the original X-l5 performance goals might still be achieved.39

Despite the relaxation of the weight requirements, the engine program failed to proceed at a satisfactory pace. On 11 December 1957 Reaction Motors reported a new six-month slip. The threat to the entire X-l5 program posed by these new delays was a matter of serious concern, and on 7 January 1958, Reaction Motors was asked to furnish a detailed schedule and to propose means for solving the difficulties. The new schedule, which reached WADC in mid-January, indicated that the program would be delayed another five and one-half months and that costs would rise to $34,400,000—double the cost estimate of the previous July.10

In reaction, the Air Force recommended increasing the resources available to Reaction Motors and proposed the use of two 11 XLR11 rocket engines as an interim installation for the initial X-l5 flights. Additional funds to cover the increased effort were also approved, as was the establishment of an advisory group.42

The threat that engine delays would seriously impair the value of the X-l5 program had generated a whole series of actions during the first half of 1958: personal visits by general officers to Reaction Motors, numerous conferences between the contractor and representatives of government agencies, increased support from the Propulsion Laboratory43 and the NACA, an increase in funds, and letters containing severe censure of the company’s conduct of the program. An emergency situation had been encountered, emergency remedies were used, and by midsummer improvements began to be noted.

Engine progress continued to be reasonably satisfactory during the remainder of 1958. A destructive failure that occurred on 24 October was traced to components that had already been recognized as inadequate and were in the process of being redesigned. The failure, therefore, was not considered of major importance.41 A long-sought goal was finally reached on 18 April 1959 with completion of the Preliminary Flight Rating Test (PFRT). The flight rating program began at once.13

At the end of April, a “realistic” schedule for the remainder of the program showed that the Flight Rating Test would be completed by 1 September 1959. The first ground test engine was delivered to Edwards AFB at the end of May, and the first flight engine was delivered at the end of July.4*

A total of 10 flight engines were initially procured, along with six spare injector – chamber assemblies; one additional flight engine was subsequently procured. In January 1961, shortly after the first XLR99 test flight, only eight of these engines were available to the flight test program. There was still a number of problems with the engines that Reaction Motors was continuing to work on; the most serious being a vibration at certain power levels, and a shorter than expected chamber life. There were four engines being used for continued ground tests, including two flight engines.47 Three of the engines were involved in tests to isolate

and eliminate the vibrations, while the fourth engine was being used to investigate extending the life of the chamber.48

It is interesting to note that early in the proposal stage, North American determined that aerodynamic drag was not as important a design factor as was normally the case with jet-powered fighters. This was largely due to the amount of excess thrust available from the XLR99. Weight was considered a larger driver in the overall airplane design. Only about 10 percent of the total engine thrust was necessary to overcome drag, and another 20 percent to overcome weight. The remaining 70 percent of engine thrust was available to accelerate the X-l5.44

RESOLUTION ADOPTED HI NACA

RESOLUTION ADOPTED HI NACA (AFFTC History Office)

(AFFTC History Office) (NASA)

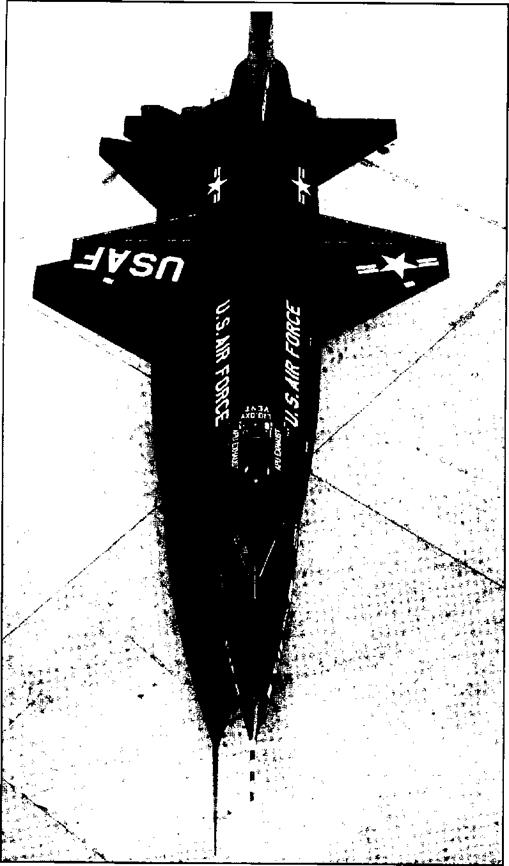

(NASA) The first X-15 (56-6670) immediately prior to the official rollout ceremonies at North American’s Los Angeles plant on 15 October 1958. The small size of the trapezoid-shaped wings and the extreme wedge section of the vertical stabilizer are noteworthy. (North American Aviation)

The first X-15 (56-6670) immediately prior to the official rollout ceremonies at North American’s Los Angeles plant on 15 October 1958. The small size of the trapezoid-shaped wings and the extreme wedge section of the vertical stabilizer are noteworthy. (North American Aviation) (NASA photo EL-1996-00114)

(NASA photo EL-1996-00114) North American test pilot A. Scott Crossfield was responsible for demonstrating that the X-15 was airworthy.

North American test pilot A. Scott Crossfield was responsible for demonstrating that the X-15 was airworthy. The X-15-2 made a hard landing on 5 November 1959, breaking its back as the nose settled on the lakebed. The damage looked worse than it was, and the aircraft was back in the air three months later. (NASA photo E-9543)

The X-15-2 made a hard landing on 5 November 1959, breaking its back as the nose settled on the lakebed. The damage looked worse than it was, and the aircraft was back in the air three months later. (NASA photo E-9543) All three X-15s normally carried a yellow NASA banner on their vertical stabilizers. (U. S. Air Force)

All three X-15s normally carried a yellow NASA banner on their vertical stabilizers. (U. S. Air Force) Six of the X-15 pilots {from left to right): Lieutenant Colonel Robert A. Rushworth (USAF), John B.

Six of the X-15 pilots {from left to right): Lieutenant Colonel Robert A. Rushworth (USAF), John B. Over the course of the program, the markings on the NB-52s changed significantly. Early on, they were natural metal with bright orange verticals; later they were overall gray. (NASA)

Over the course of the program, the markings on the NB-52s changed significantly. Early on, they were natural metal with bright orange verticals; later they were overall gray. (NASA) On 4 November 1960, the program attempted to launch two X-15 flights in a single day. Here X-15-1 is mounted on the NB-52B and X-15-2 is on the NB-52A. Rushworth was making his first flight in X-15-1, a low (48,900 feet) and slow (Mach 1.95) familiarization. The X-15-2, with Crossfield as pilot, aborted due to a failure in the No. 2 APU. (NASA photo E-6186)

On 4 November 1960, the program attempted to launch two X-15 flights in a single day. Here X-15-1 is mounted on the NB-52B and X-15-2 is on the NB-52A. Rushworth was making his first flight in X-15-1, a low (48,900 feet) and slow (Mach 1.95) familiarization. The X-15-2, with Crossfield as pilot, aborted due to a failure in the No. 2 APU. (NASA photo E-6186)

(NASA photo E63-9834)

(NASA photo E63-9834)