n the Baltic States, the German Army Group North had made considerable territorial gains during the first three weeks of the war but failed in its aim of surrounding large Soviet troop forces. Panzergruppe 4, constituting the central thrust of Army Group North, advanced in a northeasterly direction toward Leningrad. The Eighteenth Army, on its left wing, rolled into Estonia, and the Sixteenth Army, on the right, advanced in the direction of the area south of Lake Ilmen. Having penetrated more than four hundred miles into Soviet – held territory, the exhausted Panzer troops had reached a point sixty miles southwest of Leningrad at the Luga by mid-July. By this time, General Erich von Manstein’s LVI Panzerkorps had lost half its tank equipment and ran into heavy counterattacks with strong air support. A pause was inevitable. During the following weeks, Army

Group North concentrated on securing the flanks of the tank spearheads. By mid-July the Eighteenth Army had reached Dorpat while the Sixteenth had advanced fifty miles into “old Russia.”

The Ju 88 bombers of KG 1, KG 76, and KG 77 were assigned mainly to attack the heavy Soviet rail traffic in Estonia, with the hope of preventing the Soviet Eighth Army from escaping eastward over the narrow strip of land between Lake Peipus and the Gulf of Finland at Narva.

Having brought the Soviet medium-bomber raids to an abrupt end, the Bf 109s of I1./JG 53 and JG 54 were tasked to suppress the upsurge in Soviet fighter and fighter-bomber activity along the entire front line of Army Group North. The VVS fighters were particularly successful in the western sector, in the skies above Estonia

and the Gulf of Riga. In mid-July the German High Command noted that enemy fighters made air reconnaissance difficult in Estonian airspace.1′ Major Johannes Trautloft, commanding the Jagdgruppen in Fliegcrkorps I, sent his pilots out on regular search-and-destroy free-hunting missions. A favorite tactic among these Bf 109 pilots was to circle above the enemy’s fighter bases to provoke him into the air.

On the afternoon of July 19, 1941, Leutnant Walter Nowotny of 9./JG 54 took off on a fateful free-hunting mission to the island of Osel in the Gulf of Riga together with his wingman. The two Messerschmitt pilots positioned themselves above a Soviet air base with the aim of provoking enemy fighters into the air.

The Soviet 153 IAP launched four I-153 Chaykas led by Starshiy Lcytenant Aleksandr Avdeyev against the German aircraft. Later, Nowotny wrote: “The Bolshevik fighter base was located near Arensburg. As we started circling in the air above the airfield, ten fighters were scrambled. Two Curtiss 1-153s became my first two victims. . . . Moments later, I noticed a white-nosed aircraft on my tail’ Some of the planes of 153 IAP had their spinners painted white. Similarly, some Bf 109s of JG 54 had white spinners. Casting only a short glance at the aircraft behind him—noticing the white nose but not the double pair of wings – Nowotny assumed it was his Kaczmarek or “Wooden Eye” (Holzauge), as wingmen were called in Luftwaffe slang. Instead, it was the Chayka piloted by Starshiy Leytenant Avdeyev. According to a Soviet source,18 Avdeyev attacked the lead Bf 109 and shot it down with a long burst. Then he suddenly felt a hard strike and his cockpit was filled with smoke. Avdeyev found himself attacked from behind.

Avdeyev’s flying skills and the maneuverability of the 1-153 made it impossible for his pursuers to finish him off. Suddenly another Bf 109 appeared, just in front of him. The German pilot was making a combat turn. Aleksandr Avdeyev immediately pulled up his Chayka and fired a long burst Smoke started pouring out of the 109. The Soviet pilot pressed the trigger again and saw the Bf 109 go down.

Walter Nowotny recalled: “It was not until bullets slammed into my aircraft that I became aware of my fundamental mistake. Unfortunately, by then it was too late. I managed to revenge myself by sending this false wingman to the ground as today’s number three, but then my engine stopped.”

While Starshiy Leytenant Avdeyev bailed out of his 1-153 and landed in friendly territory’, Leutnant Nowotny directed his crippled Bf 109 to the south, out over the sea, in a desperate effort to bring it to the coast of German-occupied Lithuania. Nowotny failed, and spent three

days and nights in a rubber dinghy in the Bay of Riga before finally reaching the shore near Mikelbaka on the northern tip of the Lithuanian mainland.

days and nights in a rubber dinghy in the Bay of Riga before finally reaching the shore near Mikelbaka on the northern tip of the Lithuanian mainland.

: As a car arrived to bring Nowotny to the hospital,

the young pilot insisted that he should drive! Noting Nowotny’s exhausted state, the driver objected, but the Leutnant used his higher rank to push his will. The result was that Nowotny lost control over the car and collided with a tree, giving him a concussion. Finally returning to his unit, Nowotny found that his belongings had been packed and were about to be sent to his parents.

“As I started flying combat missions again, 1 had a very unpleasant feeling as soon as I had water below. I couldn’t get rid of this feeling until fourteen days later, as I managed to shoot down a Russian bomber exactly on the same spot as I had gone down.”19

During the rest of his combat career, the superstitious Nowotny always wore the trousers that he had carried during those three days in the Gulf of Riga—with exception of one mission, his last sortie, at Achmer on November 8, 1944, when he was killed flying an Me 262 jet fighter.

Avdeyev later became one of the top Soviet fighter aces, but he was killed in action thirteen months after this encounter with Walter Nowotny.

On the northern shore of the Gulf of Finland, other famous Soviet fighter aces were operating from the beleaguered naval base at Hanko. On July 23, Kapitan Aleksey Antonenko and Leytenant Petr Brinko of 13 IAP/KBF took off from Hanko together with nine I-153s on a mission against Turku Airdrome in southwestern Finland. Since no Finnish aircraft were found there, the Soviet airmen decided to look at the harbor instead. As the formation arrived over Ruissalo Seaplane Station in Turku, they were met with heavy antiaircraft fire that blew one of the biplanes apart. Nonetheless, the two well-known aces pressed home their attack, claiming two seaplanes destroyed. According to German sources, nine Soviet aircraft attacked Ruissalo, where one He 114 and an He 59 were damaged by machine-gun fire.20

But the odds during the Battle of Hanko were too uneven, as 13 lAP’s airfield came under constant artillery shelling. While Antonenko was landing after a combat mission on July 25, an artillery shell exploded right behind his 1-16. The shock wave overturned the airplane,

In the summer of 1941, twenty-four-year-old Starshiy Leytenant Aleksandr Avdeyev experienced the German onslaught on the USSR as a pilot in 153 IAP, which was equipped with 1-153 and 1-16 fighters. In 1942 this unit was one of the first to receive American-built Bell P-39 Airacobra fighters. On August 12,1942, Avdeyev was killed ramming a Bf 109 of II./ JG 77, his thirteenth aerial victory. On February 10,1943, Avdeyev was posthumously appointed Hero of the Soviet Union. {Photo: Novikov.)

and Kapitan Aleksey Antonenko, the formidable fighter and victor in eleven aerial combats, was thrown out of the cockpit and killed instantly.

The death of his friend shocked Petr Brinko. The commander of the Hanko aviation group saw this and decided to transfer him from Hanko to Tallinn, in northern Estonia. In the latter sector, the situation for the Soviet Eighth Army was deteriorating day by day. Squeezed toward the northern coast of Estonia by the German Eighteenth Army, it was in danger of being sealed off by the advance of Panzergruppe 4 to the Luga River, in the east. Leytenant Brinko arrived to join the air forces of KBF and Northern Front that were brought in to relieve pressure on the Eighth Army with aerial assaults against the enemy ground troops.

On July 23 1941. nine 1-153s led by Kapitan Leonid Beiousov and the two 1-16s pilotec by Kapitan Aleksey Antonenko and Leytenant Petr Brirkc—all frorr tie detachment of 13IAP/KBF at Hanko—set out against the Finn sh airfield at Turku. Flying in over the nearby seaplane station at Riissalo. the Soviets found two hydroplanes. Antonenko and Brinko attacked them with machine-gun f re and destroyed both, an He 114 and an He 59, pmbably from Fernaufklarungsgruppe 125. This photo shows the He 59, ‘DK+BS,’ shortly after the Soviet deadly duo’s unwexome visit. {Photo: Matti Poutavaara via Valtonen.)

On the other side of the hill, the Germans shifted the task of the bombers of Luftflotle 1 to an offensive against the supply lines leading to Leningrad, a move intended to prepare the upcoming offensive against that city. On July 25 and 27 the important rail junction at Bologoye, on the Moscow – Le n і ng r a d line, was hit decisively.

Intercepting a formation of Ju 88s over Krasno – gvardeysk, the old czar residence southwest of Leningrad, on July 27, Mladshiy Leytenant Vladimir Zalcvskiv of 157 І. ЛР/7 IAK reportedly brought down one bomber by ramming it with his 1-16. The successful Soviet рік* survived, unlike Leutnant Gerhard ZicImVs crew from 7 / KG 76, which was listed as missing in the same area.21

Having destroyed the remnants of three surrounded Red Army divisions west of the Nevel River, on the right flank of Army (Troup North, the German Sixteenth German Army mounted an offensive on July 28 against the railway junction Velikiyc Luki, a hundred miles to the east of the Russian-Lal vian border. A close-support

mission in this area on the first day of the attack claimed the life of Hauptmann Johannes Freiherr von Richthofen, the St affcl kapitan of 6./ZG 26. Badly hit by enemy fire, his Bf 110 crashed into woods, exploding on impact and creating a violent: forest fire/2

During these days, ZG 26 was followed by the remaining units of Fliegerkorps VIII, as this command was shifted from Luftflotte 2 to Luftflotle I. Bringing in four Stukagruppen and three Jagdgruppen meant a significant strengthening of the Luftwaffe forces available for support of the upcoming offensive against lxningrad.

Assembled in the Velikiye Luki sector, IIl./JG.5.1 achieved JG 53’s thousandth victory on July 29. On the last day of July, the famous Slarshiy Leytenant Petr Ryabtsev (12.5 IAP), who had been one of the first successful air-to-air rammers on the first day of the war, was shot down and killed by a Grunherz fighter. On the following day, Leutnant Max-Hellmuth Ostermann achieved the Grunherz Gesehwader s thousandth victory.

The rate of attrition in the Soviet air units is clearly – depicted by the losses sustained by VVS-North western Front. Unable to count more than approximately 150 aircraft on July 1, 1941, VVS-North western Front alone registered 189 planes lost in combat (including 132 on combat missions, with a further 4 receiving heavy battle if damage) in July.2′ Even this figure is incomplete, since the number of Il-2s listed as lost according to this source I is 19, while the unit records of 74 ShAP/VVS-North – | western Front lists 25 Il-2s lost in July 194124—a fear – some loss rate. After the first month of the war, the I strength of VVS-Northwestern Front had been reduced

■ to only 88 aircraft, including just seventeen SB bomb – P ers.25 A total of 184 aerial victories credited to the fliers

of WS-North western Front during the same period was a poor consolation.

To the costly aerial combat were added the crippling blows dealt by the Luftwaffe against the Soviet air bases, г Responding to complaints from the German Eighteenth I Army about the increased VVS activity in Estonia, ZG -■ 26 was called on to launch a raid against the large air

■" base at Tallinn. The low-level “Hun rides” against air – ; fields deep inside enemy territory were specialities of the Bf 110 crews of ZG 26. This Zerstorergeschwader was І credited with the destruction of 620 Soviet aircraft on і the ground or in the air between June 22 and July 31, ‘ 1941.

ZG 26 managed to catch the Soviets і at Tallinn Airdrome by surprise on August 2. The Bf 110 crews returned home with claims of about forty enemy aircraft destroyed on the ground. In aerial combat with Soviet aircraft, the heavy Ї Zerstorer planes were able to score far t better than during the Battle of Britain.

; t The Soviet naval fighter ace,

[; Levtenant Vasiliy Golubev, recalls a very unpleasant encounter with the Bf 110s ofZG 26. Early one morning, 13 OIАЕ/

KBF was scrambled just as two formations of twin-engine German planes came in to raid the airfield. Leytenant Golubev l’- decided to attack what he assumed to be

■ four Ju 88 bombers head-on and was sur – i prised that the enemy pilots made no attempt to evade his attack. Having the

Л enemy leader in his gunsight, Golubev

was just about to press his trigger when the nose of the enemy aircraft seemed to explode. Instantly, 20mm shells slammed violently into the Ishak’s engine and large flames erupted. Golubev instinctively pushed his stick forward, and the enemy aircraft flashed by above him. Only then did Golubev realize that they were Bf 110s equipped with powerful nose armament, and not Ju 88 bombers

Fortunately for Golubev, the airfield was right below, but the Zerstorer pilot came back to finish his kill. At this moment, Golubev’s faithful wingman, Leytenant Dmitriy Knyazev, got on the Bf 110’s tail and hit it with his four machine guns. While Golubev made a quick belly landing, Knyazev continued after the Bf 110, which, with smoke pouring out of one engine, had become separated from its flight. Knyazev finished it off in the vicinity of Narva.26

Meanwhile, the bombers of Fliegerkorps II and VIII continued striking at the Soviet rear area. On August 4, German bombers managed to completely destroy the railway station at Toropets, reporting four trains with about eighty railway cars destroyed. Obviously these missions were carried out without the bomber crews being much troubled by the Soviet fighters in this sector. According to Hauptmann Gerhard Baeker of IIL/KG 1: “Early on August 5 we flew against troop columns near Staraya Russa, and during the afternoon an ammunition depot

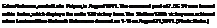

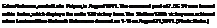

On August 6,1941, Oberleutnant Reinhardt Hejn, staffelkapitan of 2./JG 54, went down over Soviet territory and was captured. Nine days later, these photos appeared in Leningrad Pravda. In the center, Red Army soldiers are seen examining Hein’s belly-landed Bf 109 F-2. To the right is Oberleutnant Hein, who has received first aid, with armed guards. A close comparison of German and Soviet documents shows that it is highly likely that Hein was Starshiy Leytenant Andrey Chirkov’s seventh victory, reportedly achieved in the vicinity of Lake Samro, about twenty miles from Narva. According to Soviet sources, the German pilot, an Oberleutnant, was interrogated in the headquarters of 158IAP. (Photos: TASS/Leningrad Pravda.)

at Luga was our target. During all of our missions we had to deal with Russian antiaircraft fire, and sometimes also fighters, mostly Ratas. The latter didn’t trouble us very much when they attacked separately. But the Russian antiaircraft fire was effective and dangerous at all flight levels.”

To counter the appearance of Fliegerkorps VIII, four new Soviet aviation regiments arrived as reinforcements to the Northwestern Zone. Starting on August 3, the

Soviet Air Force intensified its air assaults against all sectors of Army Group North. The German Eighteenth Army in Estonia sustained particularly heavy losses.

On August 6, ZG 26 returned to Estonian airspace on another “Hun ride,” reportedly completely annihilating the entire aircraft park at a KBF seaplane station. Probably on the same day, 158 IAP/39 IAD, equipped with Yak-Is, suffered a severe setback as Bf 109s of I./ JG 54 shot down an entire formation of three fighters in a single dogfight. Starshiy Leytenant Andrey Chirkov, with seven victories to his credit at this time, survived a forced landing in friendly territory after bringing down one Bf 109. The German pilot, Oberleutnant Reinhardt Hein of 2./ JG 54, was slightly injured and subsequently captured.

On August 7, 1II./KG l’s Hauptmann Gerhard Baeker experienced a staggering example of the strengthened Soviet fighter force in this area:

I was supposed to raid the airfield at Nizino, southwest of Leningrad, together with two aircraft of the 9th Staffel. The weather was bad, with a cloud ceiling of only 150 to 300 feet above our base. The Jagdgruppe com-

manded by Hauptmann Dietrich Hrabak [II./JG 54J was supposed to escort us, but it couldn’t take off due to the adverse weather conditions, so l was tasked with the mission of a solo flight.

1 took off at 0825 and immediately sought refuge in the clouds. To the east of the Luga River, the cloud ceiling rose slowly to 6,000 feet. 1 remained close beneath the clouds so that I would be able to disappear into the haze in case of a fighter attack. Just ahead of the target the clouds dispersed, and all that was left were a few cloud mountains at an altitude of between 3,000 and 6,000 feet. I approached the airfield at 7,500 feet flight level, but just as 1 was about to launch my bomb load 1 found a huge cloud between myself and the target During my second approach flight, 1 noticed that the Soviet fighter defense had been alerted, so I made a quick dive-attack and then climbed into the closest cloud. As I came out of the cloud, 1 was met by three Ratas (IT 6). 1 gave full throttle and attempted to reach the cloud cover at 2,000 feet altitude to the west. The Ratas had difficulties in following me, but suddenly nine modern fighters approached—low-winged planes with retracted undercarriage (MiG-Is?). Realizing that 1 had no chance of reaching the clouds, I put the nose of my Ju 88 down, but before I had even commenced my dive the nine fighters were on me. I found myself in the midst of a flood of tracers. Parts of my aircraft were torn off. My left aileron no longer responded and I found it very difficult to move the side rudder. One thought went through my mind: "It looks as though you’re going to be shot down.” But I soon came to my senses. My engines were still running and 1 was diving. The first attack was over. I managed to pull my Ju 88 up and headed for the west at treetop level. None of my crewmen had been injured.

Next, the Soviets made one single pass after another. 1 flung my head in all directions, to watch the ground, to check behind, to follow’ the attacking enemy fighters with my eyes. The Russians committed a decisive mistake—they all attacked singly, below and to the left. As long as I could see the muzzles of their arms, nothing happened to me, and when they attempted to fire with the necessary aiming off, I pushed the controls of my

Hauptmann Gerhard Baeker served as technical officer in III./KG 1 Hindenburg during the first two months of Operation Barbarossa. On August 19,1941, he was severely injured in a forced landing due to engine failure on his 132nd combat sortie. Returning to front-line service in 1944, he flew four-engine He 177s with KG 1 and ended the war as Gruppenkommandeur II./JG 3. (Photo: Baeker.)

damaged rudders to the right. This went on for about thirty minutes, until we reached Luga. There, the last Soviet fighter made a final attempt to finish me off just as I had to pull up in front of the steep river bank. But I was prepared, and he failed to hit me. The Luga River was the front line. By now I was over friendly territory, and the last Soviet fighter disengaged.

As long as I had remained high, my gunner, Feldwebel Hein Bruns, fired below to the rear and my radio operator, Unteroffizier Hans Jager, fired above to the rear. At low level, only my radio operator was able to fire with his MG 15. He met

every attack with well-aimed bursts. The gunner and my observer, Feldwebel Zens, handed him new magazines as he emptied one after another at a rapid pace. Within a short time he had expanded all our ammunition magazines. There were only a few rounds left. Only when the situation became precarious did he give the enemy a pair of short bursts. Three Soviet fighters were shot down. One Rata was caught in the air current of my propellers at low altitude and crashed into the ground. Two MiGs were shot down by my crew.

After we landed successfully on one wheel at our base at Sabarovka, we counted five cannon and seventeen machine-gun hits in our Ju 88. The fuel tanks had been shot through, but they remained functional due to the self-sealing device. The antenna above the cockpit was also shot through, and the left aileron was severely damaged.

On the evening of August 7, bombers of KBF raided the German supply port at Pamu, in southwestern Estonia. A few hours later, the Soviets stunned their enemy by dispatching an air raid against Berlin.

The idea of raiding Berlin was promulgated by the commander of naval aviation, General-Leytenant Semyon Zhavaronokov, in July 1941. Having drawn up the technical plans for the raid, he introduced the plan to the

Polkovnik Yevgeniy Preobrazhenskiy, the commander of WS-Red Banner Baltic Fleet’s 1 MTAP, was one of the ablest Soviet naval aviation regimental commanders in 1941. In January 1942, 1 MTAP-KBF was among the first naval aviation regiments to receive the honorary title “Guards Regiment’. (Photo: Author’s collection.) commissar of the Soviet Navy, Admiral Flota Nikolay Я Kuznetsov. According to Zhavaronokov’s plan, all bomb Я ers in VVS-KBF would participate. The main problem ■ was that only one air base, at Osel Island, permitted the ■ bombers to reach Berlin. Kuznetsov presented the plan I to Stalin. The Soviet dictator accepted, but only agreed Я to the use of two Eskadrilyas of 1 MTAP.

General-Leytenant Zhavaronokov was put in charge Я of the Berlin raid. On July 30 he arrived in Bezzabotnoye Я Airdrome, where he met the commander of 1 MTAP/Я KBF, Polkovnik Yevgeniy Preobrazhenskiy.

The call for a Berlin raid did not come as a surprise* to Preobrazhenskiy. A few days earlier, he had instructed I his regiment’s chief navigator, Kapitan Petr Khokhlov, Я to investigate the possiblities of launching a mission against Я the German capital. The total distance from Osel to Вег – Я lin and back again was more than eleven hundred miles, Я which implied a flight duration of seven hours for the Я DB-3T bombers. This allowed no more than twenty-five Я minutes of fuel reserve.

Polkovnik Preobrazhenskiy ordered twenty DB-3Ts Я to be prepared for the mission. Some of these aircraft underwent certain technical improvements, including the j installation of powerful radio transmitters. Five planes j had their engines exchanged. The best and most expert j enced crews were singled out and interned in a closed zone two miles from the air base, with strict orders that prohibited any contact with outsiders.

At 2300 hours on August 4, fifteen DB-3Ts (the remaining five were still waiting for engine exchanges) і took off from Bezzabotnoye. After a flight of 375 miles, j they landed at Kagul/Osel Airdrome. On August 7, ] weather recce flights to the German Baltic Sea coast were J undertaken by some daring fliers in Che-2 aircraft from j the same airfield. Despite reports of adverse weather 1 conditions-low clouds at 2,500 to 3,000 feet in altitude, 1 and rains—General-Leytenant Zhavaronkov decided to launch the raid that very evening.

At 2100 hours, thirteen bombers started taking off against Berlin. With the exception of one aircraft, which ] carried a 1,000-kilogram bomb load, each DB-3T carried j two 100-kilogram ZAB incendiary bombs and six 100- kilogram FAB high-explosive bombs.

The approach flight was carried out at an altitude of 18,000 feet, the crews having to endure temperatures j of 37 degress Celsius below zero. After three hours, the first ] bombers arrived over Berlin. According to the Soviet ver – 1

[ sion, Polkovnik Preobrazhenskiy dropped the first bombs. 1 He then radioed Osel: “Target Berlin, mission accomplished!" 1 MTAP reported six bombers arriving over j the German capital, with the remainder dropping their bombs on targets of opportunity.

In his chronicle of the Berlin raids during World War II, historian Werner Girbig gives the German ver – [ sion: “The Russians dispatched a small group of Ilyushin [. Il-4s [DB-3Ts|, which reached the Berlin area but never undertook any real attack. Only one single aircraft appears to have dared enter the airspace over the city’ itself. I Approximately forty minutes after the alarm was sounded,

I several searchlight beams caught the twin-engine Russian aircraft. The pilot maintains his course stubbornly, I without making any evasive maneuvers. The antiaircraft К artillery opens fire. After a few minutes the 11-4 is covered with flames. It goes down in a steep dive and crashes I somewhere in the outskirts of the city. On the following day, the widespread wreckage of the Soviet bomber is I examined closely by air force specialists.”27

According to the Soviet version, all aircraft returned, F though one DB-3 crashed at the airfield due to poor I ground illumination. After the landing, the Soviet airmen I celebrated with a whole box of brandy. 1 MTAP carried out I two more raids against Berlin during the following nights.

The air activity reached a new climax along the entire northern combat zone after August 8, when Panzergruppe 4 opened the final offensive against Leningrad on the Luga front, southwest of the city. On the first day of the offensive, heavy rain hampered most air activity. General-Leytenant Markian Popov, the commander in chief of the Northern Front, called for large – scale airstrikes against the German area of deployment. This was a difficult task, because his battered air force was widely dispersed. Of 560 aircraft available on August 10, 142 were deployed along the Finnish border and farther north, in the Murmansk area. VVS-KBF was engaged supporting the Soviet Eighth Army in northern Estonia. General-Mayor Aleksandr Novikov, the supreme VVS commander in the Northwestern Zone, decided to shift 2 BAD from the area south of Lake Ilmen and 7 IAP/5 SAD from the Karelian Isthmus to the Luga sector.

With clearing skies on August 10, the air forces on both sides launched all available aircraft in close-support missions in the Luga sector. The impact was terrible. On this day alone, 1,126 Luftwaffe sorties and 908 VVS sorties were logged. The German airmen claimed to have destroyed ten tanks, more than two hundred vehicles,

and fifteen artillery batteries on August 10.28 On the Soviet side, 288 ShAP claimed large successes in low – level attacks against concentrations of enemy motorised troops.

By the end of the day, the Luftwaffe counted fifty – four Soviet warplanes shot down.24 The participating German fighter units suffered only three losses, one of them through a ramming by a MiG-3 piloted by Kapitan Ivan Gorbachyov of 71 LAP/KBF. According to Soviet figures for August 10, VVS-Northern Front shot down twenty-three German planes against eleven of its own planes lost.30

The air strikes enabled Pansergruppe 4 to penetrate the Soviet defense positions on August 11, initiating the drive toward Leningrad. But despite the heavy Luftwaffe air strikes, the Soviet resistance continued to be very hard. The Panzergruppe was only able to move forward slowly in the marshlands on the way to Leningrad, fighting bitterly for every step ahead.

The largest Soviet aerial effort against Berlin took place on the night of August 11. It involved both Podpolkovnik Preobrazhenskiy’s naval aviation regiment and aircraft from DBA: DB-3s and DB-3Fs from 200 BAP at Osel; plus eight TB-7s from 432 BAP/81 AD; and three Yer-2s from 420 BAP/81 AD based at Pushkin, near Leningrad. The four-engine TB-7 bombers were personally led by the commander of 81 AD, Kombrig Mikhail Vodopyanov, a veteran and Hero of the Soviet Union.

The mission was a complete failure. One TB-7 crashed during takeoff. Since the KBF had not been informed of this mission, two other TB-7s were mistakenly shot down by friendly antiaircraft batteries, while a third was downed by a KBF 1-16. Two other TB-7s returned home with heavy AAA damage sustained over enemy territory, and both were destroyed in crash landings. One Yer-2 was listed as missing. Only three TB-7s and two Yer-2s managed to reach Berlin.

Kombrig Vodopyanov’s own experiences are quite telling. During the approach flight, bis TB-7, Blue 8, found itself bounced by a group of 1-16s, but it luckily managed to escape without getting hit. Having strayed off course, the crew of the bomber managed to locate Stettin, eighty miles northeast of Berlin, where it ran into a heavy antiaircraft barrage. Despite one engine out of action due to damage, the crew succeeded in bringing the plane to the Berlin area, where the bombs were salvoed somewhere in the northern outskirts shortly after midnight. Twice hit by antiaircraft fire again, Vodopyanov’s TB-7 went! down in a forested area in German-occupied southern Estonia. After a two-day walk, the crew managed to reach the Soviet lines, only to learn that Vodopyanov had been; relieved of his command and replaced by Polkovnik Aleksandr Golovanov, who later rose to command the entire Soviet strategic bomber force.

These minor Soviet raids naturally had no influence. on the general war situation. The defenders of Leningrad! saw the enemy approach closer day by day. Despite tena – cious efforts by the ground troops and the airmen of the Red Army, the advance of the enemy tank spearheads seemed to be slowed but not entirely halted. On August 13, Panzergruppe 4 reached the rail line connecting! Tallinn, in northern Estonia, with Leningrad. With that General-Mayor Novikov decided to reinforce the air units on the Luga-Leningrad front with 126 navy aircraft, the hulk of WS-KBF.

The scale and pace of operations inevitably wore down the Red air units. On August 13, a successful naval air force pair, Lcytenant Vasiliy Golubev and Leytenant Dmitriy Knyazev of 13 OlAE/KBF, were shot down. Flying air cover for the Tallinn rail line on the northern coast of Estonia, a group of I-16’s led by Starshiy Leytenant Petr Kulakov was jumped by a Staffel of Bf 109s. The Soviets managed to evade the first attack without suffering any losses, but the Bf 109s came back. A whirling dogfight followed in which the Soviet pilots had to use all their flying skills. Leytenant Knyazev’s Ishak was shot down in flames, and Knyazev bailed out, Leytenant Golubev was eventually defeated when a Bf 109 sneaked up on his tail. A violent strike told Golubev that his aircraft was hit. As he turned away, he felt another strike, this time from below. His flight altitude was too low by now, and the ground was rushing toward him. Hot oil splashed onto his face and covered his goggles; he threw them off and saw a small wood in front of him. Having slowed by turning off the engine, Golubev managed to pull the stick by using all his strength and both hands. Then followed the crash. Vasiliy Golubev returned to conciousness only on the following day.31

Leutnant Max-Hellmuth Ostermann of 7./JG 54 Griinherz later described a most difficult air combat with a Soviet fighter pilot in the same area on August 4:

The Russian flight leader had noticed us and

turned around. My wingman made another attack. Once again, the Russian turned and met him head – on. Damn, this was a tough fellow!

turned around. My wingman made another attack. Once again, the Russian turned and met him head – on. Damn, this was a tough fellow!

The rest of my flight intervened and made wild attacks on him from all positions. This Russian pilot definitely was one of their top aces. He avoided each attack exactly at the right moment, pulled up, and then went down steeply over his wing. He even had the nerve to pull up behind our flight and fire some very accurate bursts. We lay above him, dove on him at high speed, and then pulled up steeply. So far, 1 hadn’t intervened

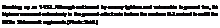

7./JG 54’s Leutnant Max-Hellmuth Ostermann was one of the most aggressive fighter pilots of JG 54 during the early years of the war with the USSR. He was so short in stature that his Bf 109 had to have wooden blocks attached to the rudder pedals. Nevertheless, Ostermann was one of the few German fighter pilots who dared to enter—and was able to win—turning combats with the highly maneuverable Polikarpov fighters. He later became famous for his long-range sorties, searching out victims over airfields far in the Soviet rear area. Ostermann was killed during one of these sorties, on August 9,1942, after having achieved a total of 102 victories. (Photo: Bundesarchiv.)

Leytenant Vasiliy Golubev of 13 OIAE/KBF was one of the noblest aerial opponents of the Bf 109s of JG 54 Griinherz during much of the war. He scored his first victory, against a Ju 88 on June 28, 1941, and through August 1941 he succeeded in bringing down a total of eleven enemy aircraft, most of them jointly with his faithful wingman, Leytenant Dmitriy Knyazev. Golubev finished the war with a total of sixteen personal and twenty-three shared victories. He reached the rank of leytenant-general before retiring in 1975. (Photo: Seidl.)

in the combat, since I wanted my Kaczmarek to have this kill. But suddenly the Russian tried to get away, heading for two Russian naval ships anchored in the bay. The AAA on the ships was already firing at us. It was now or never! I went down after him, but he turned to the right. I had aimed slightly to the left, but he had noticed this immediately. As I pulled up again, he had already banked to the left. Then he came around and started shooting at me from behind! Suddenly, light AAA fire opened up at me from the ships. I turned left as hard as I could, went down over the left wing, and then pulled left again. 1 made this very fast, and got the Russian in front of me. From

slightly above him, I finally managed to get a burst at him. I could see hits! The plane left a trail of dark smoke.

When Leytenant Golubev returned to 13 OIAE a month later, he would find only nine I-16s left of the original twenty-six.

On the right wing of Army Group North, the German Sixteenth Army approached Novgorod north of Lake Ilmen. The immediate aim of this attack was to sever the important supply line from Moscow to Leningrad. During a battle lasting eleven days, both sides sent strong air forces to this sector. The air units of Luftflotte 1 fell upon the retreating Soviet columns, while VVS-North – western Front and DBA units carried out 460 sorties against the advancing German troops. On August 13 Gefreiter Erich Peter, a newly arrived dive-bomber pilot in 3./StG 2 Immelmann, managed to interrupt the Soviet retrograde movement by knocking out a vital bridge across the Volkhov River. The next day, a formation of Bf 109s bounced a group of Soviet aircraft carrying out low-level attacks near Lake Ilmen and downed seven-

five of them by Oberleutnant Erbo Graf Kageneck of III./JG 27—without suffering any losses. The I Staffelkapitan of 4./JG 52, Oberleutnant Johannes! Steinhoff, scored one victory in the same area. One of his pilots was killed in combat with eight DB-3s of 1 BAK and four of the new 11-2 Shturmoviks. That day, also, 288 ShAP was reported to have destroyed > or damaged more than fifty vehicles in a single German supply column near Soltsy, southwest of Lake Ilmen.

During one of the 155 sorties flown by KG 2 on August 14, the Do 17 piloted by Knight’s Cross holder: Leutnant Heinrich Hunger received a direct AAA hit! and crashed near Novgorod. The crew managed to bail out. Later, the remains of Leutnant Hunger and his radio operator were found, butchered by their Soviet captors.

On August 16, as Novgorod fell into German hands, the Soviet Eleventh and Thirty-fourth armies opened a counterattack south of Lake Ilmen, at Staraya Russa. KG 1 77 and the entire Fliegerkorps VIII were immediately brought into action against this threat. Dive-bombers and Zerstorer carried out close-support attacks while the

Ju 88s and Do 17s struck against troop columns and railway lines leading to Staraya Russa, inflicting severe casualties. The bombers of Fliegerkorps I meanwhile were fully engaged against Soviet rail supplies, and on August 16 Hauptmann Gerhard Baeker of I1I./KG 1 managed to sever the rail line to the Luga front. On August 17 six Do 17s, led by Oberleutnant Werner Lutter of Stab/ KG 2, managed to destroy eighteen Soviet tanks during a single mission west of Staraya Russa.

Despite a successive decrease of the number of serviceable aircraft, the WS continued to present problems to the Luftwaffe in the air. In his chronicle of KG 2, Ulf Bailee made the following note for August 16: “Very strong enemy fighter opposition made the task of the bombers difficult Only due to the Me 109F fighters of fll/JG 54, which flew continous free-hunting missions over the battlefield, were the losses limited to one Do 17 of 9./KG 2, which was forced to belly-land near Vereteni with heavy damage from enemy fighters.”32

The strong offensive action by the WS compelled the Luftwaffe to resume its air-base offensive. Soviet figures, however, show a meager outcome, with only six aircraft of VVS-Northern Front destroyed on the ground on August 16.

During one of these raids, a formation of twenty – four Bf 110s of I./ZG 26 and four Bf 109s of III./JG 54 were intercepted by five courageous MiG-3 pilots. The Soviets claimed four enemy aircraft shot down. I./ZG 26 recorded one Bf 110 heavily damaged while 8./JG 54 Grunhcrz lost Oberfeldwebel Georg Braunshirn, a thirteen-victory ace. Braunshirn was the first among the Griinherz top aces to fall on the Eastern Front.

The logbook of 7./JG 54 on August 18 reads: “The Staffel is involved in daily air combat with numerically superior enemy formations southwest of Leningrad. These engagements frequently last for an hour’s time. The maneuverability of the Russian fighters makes it hard to shoot them down. Leutnant Ostermann nevertheless

Oberleutnant Hans Philipp, the Staffelkapitan of 4./JG 54, was the top scorer of JG 54 in 1941. On August 24,1941, after he had scored his sixty-second victory, he was awarded the Oak Leaves to his Knight’s Cross. This photo shows Philipp a few days before the award ceremony, posing beside the rudder of his Bf 109 F, which displays fifty-six markings. By the time Philipp was killed in combat with U. S. heavy bombers and Thunderbolts on October 8,1943, he had achieved a total of 206 victories. (Photo: Hofer.)

managed to bring down two l-lbs today.”55 The top ace in JG 54, Oberleutnant Hans “Fips" Philipp, of II Gruppe, scored his sixtieth victory during these fights.

To the west, the Battle of Estonia was settled during the latter half of August. On August 19, eight 13 1АР/ KBF Ishaks took off from Tallinn to strafe a column of German troops on the road from Parnu to Tallinn. This cost them three 1-16s damaged, of which one, piloted by Leytenant Alim Baysultanov, exploded shortly after landing.

Striking against the Soviet air units that supported the Red Army in the Leningrad sector, ZG 26 was dispatched on August 19 against the base of 5 ІЛР/KBFal Nizino, seventeen miles southwest of Leningrad. Oberleutnant Johannes Kiel of I./ZG 26 later wrote the following vivid account of this raid:

We started diving from an altitude of 3,000 meters, J right into the antiaircraft fire. AAA bursts appear to the left, to the right, and between our aircraft And still we continue toward our target. Battle excitement has caught us. Each of us concentrates only on the target. We approach the airfield rapidly. Each pilot has singled out his target The

ground comes rushing toward us, as if it is going to consume us. Five hundred, three hundred, one j hundred meters. Our guns start hammering. The Zerstorcrgruppe comes sweeping down over the j airfield, only a few meters above the ground. Here and there we can see enemy aircraft burst into I flames, and then we climb again. A wild circus is J commenced. The formation is split as each pilot | seeks his target. The aircraft dive upon their victims from all directions….

‘‘Achtung! Fighters from the left!” The en – j emy fighters have arrived already! Everything is! on fire on the airfield beneath us. Heavy explo – j sions are sounding and there is thick smoke in the air. We dive into the smoke over and over again, and discover more hidden aircraft. As in a dream,

1 can sec one of our own aircraft disengage with a j thick trail of smoke—hit by antiaircraft fire. The j damaged plane is turning away to the west. It starts losing altitude, goes deeper and deeper. There. It hits the ground.

From the Soviet viewpoint, Leytenant Igor Kaberov | of 5 IAP recalled this raid: “A huge formation of enemy aircraft dove out of the sun and came roaring over the hangar roofs. The whisde from falling bombs and rattling of machine guns deafened me. I threw myself to the ground and saw the twin-engine Messerschmitts rush over the runway. 1 waited for the right moment, then I stood up and dashed to the shelter. Having almost tom the door from its hinges, I jumped in and flung myself flat to the floor. Someone pulled me into a corner of the shelter. Moments later, a machine-gun burst pierced the door and the tables close to it The lights went out. In the darkness we listened to the seemingly endless

machine-gun fire, bomb explosions, and roaring aircraft engines.*34

machine-gun fire, bomb explosions, and roaring aircraft engines.*34

According to Soviet sources, twenty Soviet aircraft were destroyed on the ground and a further thirteen received damage of varying degrees during this raid.35 Only one pilot, Mladshiy Leytenant Nikolay Sosedin, managed to take off during the raid, and he crashed his 116 on the runway, sustaining severe injuries. Two days later, one Eskadrilya of 5 1AP/KBF was pulled out of combat to reequip on LaGG-3s.

The airmen of L./ZG 26 claimed the destruction of forty Soviet aircraft on the ground, plus three in the air, for the loss of one Bf 110. With this, ZG 26 had increased its toll of enemy planes destroyed since June 22 to 191 in the air and 663 on the ground.

On August 20 the German Sixteenth Army finally managed to capture Chudovo, north of Novgorod, thus cutting off one of the two main supply lines between Moscow and Leningrad. During this eleven-day battle the units under command of Fliegerkorps VIII had dropped more than thirty-three hundred tons of bombs.

The next day, Panzergruppe 4 reached Krasno – gvardevsk, thirty miles southwest of Leningrad. Instead of concentrating the entire armored force against Leningrad, the commander of Army Group North, Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb, ordered

the XXXI Panzer Corps to turn south. The plan was to surround the Soviet troops remaining in the Luga – Novgorod area. During renewed Luftwaffe air-base raids on August 21, VVS-Northern Front registered eighteen aircraft lost on the ground at Pushkin.

To improve the structure of the defense operations at Leningrad, the Stavka divided the Northern Front, responsible for the huge sector between Leningrad and Murmansk, into two new fronts: the Karelian Front, mainly in charge of the Soviet-Finnish combat zone; and the Leningrad Front.

On August 25, Mladshiy Leytenant Petr Kharitonov of 158 IAP reportedly downed a Ju 88 near Krasnogvardeysk by ramming it; then he successfully bailed out. According to a Soviet source,36 the four-man crew of the German bomber bailed out and, from a position above Kharitonov, opened fire at the fighter pilot with their flight pistols. Another Yak-1, piloted by a young Leytenant, came to Kharitonov’s assistance with blazing guns, killing one of the German airmen while he was hanging in his harness. As they reached the ground, the three surviving Luftwaffe aviators were captured by infuriated Red Army soldiers. The loss lists of Generalquartiermeister der Luftwaffe reveal that a Ju 88 of 6./KG 76 was lost to Soviet fighters in the same area on that day. The entire crew w’as listed as missing, with the comment that two airmen probabably managed to bail out.

Kharitonov was awarded the Golden Star as a Hero of the Soviet Union. This was his second taran—the first being achieved with his 1-16 over another Ju 88 in the vicinity of Pskov in the Soviet – Estonian southern border area on the seventh day of the war. Shortly aftenvard Kharitonov was shot down and seriously w’ounded in air combat. He returned to the front only in 1944, ending the war in the PVO with sixteen victories to his credit.

Another Soviet fighter pilot shot dow-n and killed the Staffelkapitan of 1./ KG 2, Oberleutnant Horst Scharf von Grauerstedt, south of Chudovo, near the Volkhov River on August 25.

Intense fighting along the extended front line on the northern combat zone

lay an increasing burden on the exhausted combat pilots of both sides.

To the south, on the border between Army Group North and Army Group Center, a prolonged battle was being waged at Velikiye Luki, where a Soviet counterattack was halted with the help of Fliegerkorps VHL This resulted in the complete destruction of the Soviet Twenty-second Army. Here, 40,000 Soviet soldiers perished and 30,000 were captured, a high price for merely slowing the German advance against the sector between Lake Ilmen and Moscow. Operating over this battleground, the Bf 109s of I1I./JG 53 Рік As took a heavy toll of WS-Northwestern Front, reinforced to muster 174 aircraft on August 22. On August 25, Oberfeldwebel Stefan Litjens of 111.,/JG 53 repeated Oberleutnant Erbo

To the south, on the border between Army Group North and Army Group Center, a prolonged battle was being waged at Velikiye Luki, where a Soviet counterattack was halted with the help of Fliegerkorps VHL This resulted in the complete destruction of the Soviet Twenty-second Army. Here, 40,000 Soviet soldiers perished and 30,000 were captured, a high price for merely slowing the German advance against the sector between Lake Ilmen and Moscow. Operating over this battleground, the Bf 109s of I1I./JG 53 Рік As took a heavy toll of WS-Northwestern Front, reinforced to muster 174 aircraft on August 22. On August 25, Oberfeldwebel Stefan Litjens of 111.,/JG 53 repeated Oberleutnant Erbo

Graf Kageneck’s previous feat by knocking another five Soviet fighters out of the air, including four “MiG-Is” (in reality probably MiG-3s).

Graf Kageneck’s previous feat by knocking another five Soviet fighters out of the air, including four “MiG-Is” (in reality probably MiG-3s).

In total, VVS-Northwestern Front registered 115 aircraft lost in combat during August 1941, against 88 victory1 claims from July 22 to August 22.37 Most VVS units suffered unbearable losses. Among those that suffered worst was the 11-2-equipped 74 ShAP/VVS – Northwestern Front, which registered twenty-five aircraft lost in July and nineteen in August.38 7 LAK/PVO registered fifty-two fighters lost out of a total of only about one hundred fifty—and those only from August 20 to 30.34

Stiff air battles were fought over the bridgehead established by the German Sixteenth Army at the Lovat River, south of Lake Ilmen, where the VVS made repeated attempts to destroy the river crossings. For the first time in several weeks in this sector, the Soviet airmen appeared in formations of up to twenty aircraft. On August 27, II1./JG 53 claimed no fewer than seventeen victories in a single engagement, surpassing the five-hundred-victory mark of the Gruppe. On the same day, II./ JG 53 claimed another ten victories, including three by Feldwebel Herbert Rollwage.

On the Soviet side, 35IAP/7 LAK was credited with five enemy aircraft, including three Bf 110s, shot down on August 27, and six on August 29-all for the loss of only one MiG-3 on each date. Mladshiy Leytenant Nikolay Shcherbina had three of these victories. None of these claims can be verified with Luftwaffe loss lists.

To the north, a hard blow to the defenders was dealt with the German seizure of the Estonian capital, Tallinn, on August 28. The Soviets launched a large naval fleet to evacuate the Tallinn garrison, but the evacuation units quickly drew the attention of the Luftwaffe. The bombers of Luftflotte 1 had two field days on August 28 and 29. Commanded by Hauptmann Klaus Noske, on August 29 nine He Ills of L/KG 4 managed to sink three ships with a total of six thousand tons and damage another three by using the tactic of a stream of individual low-level attacks against the evacuation fleet in a single mission.40 In total, the German bombers succeeded in sinking eighteen vessels of the evacuation fleet.41 Another thirty-five vessels were destroyed by mines or Finnish torpedo boats.

One of the emerging Soviet top aces of 1941, 191 lAP’s Mladshiy Leytenant Yegor Novikov, claimed an extraordinary success on August 29: He reported downing two Ju 87s and a Bf 109 near Mga in a combat ending with Novikov himself being shot down and wounded. With this, the Soviet fighter pilot had reached a total score of four.

At Lake Ilmen, the battle reached a critical stage during the last days of August, with the Wehrmacht attacking to the north and the Red Army counterattacking to the south of the lake

While escorting six Pe-2s of 514 PBAP and four ll-2s of 288 ShAP against the base of II./JG 52 at Soltsy to the west of Lake Ilmen on August 29, nine MiG-3 pilots of 402 IAP spotted a Bf 110, which Mayor Konstantin Gruzdyev attacked. It took a prolonged air combat before he finally managed to finish off the Bf 110. (4./ZG 26 filed the loss of the Bf 110 piloted by Feldwebel Karl Grinninger in the same area.) Mayor Gruzdyev was one of the most skillful Soviet pilots in the Northwestern Zone at this time. When he was recalled from combat duty to continue to serve as a test pilot in February 1942, he had achieved a total of seventeen victories and was one of the top scorers in the entire VVS.

A dive-bomber mission on the same day deprived Fliegerkorps VIII of one of its most brilliant Stuka aces,

Knight’s Cross holder Hauptmann Anton Keil, the commander of IL/StG 1. During an attempted forced landing in enemy territory, Keil’s Ju 87 overturned, killing both crew members. The aircraft was afterwards set afire by Soviet troops.42

At the end of August, the pincer movement initiated by XLl Panzer Corps succeeded in closing in the remnants of the enemy forces in the Novgorod-Luga area. The largest annihilation battle on the northern combat zone rapidly unfolded, but the outcome was not more than twenty thousand Soviets being taken prisoner.

At this point the German fighter units in the northern combat zone were temporarily reinforced with IV./ JG 51. This Jagdgruppe included some of the most brilliant German fighter pilots of the time. One of the most notable was Oberleutnant Heinz “Pritzl” Bar, who had achieved an amazing victory total since the opening of the war with the USSR, increasing his kill tally from seventeen to seventy in only two months. In action in the northern combat zone, he surpassed his own personal one-day record by downing six enemy planes on August 30 alone. Nevertheless, the fighting on August 31 almost cost Bar his life.

After scoring his seventy-ninth and eightieth victories against two Pe-2s, Bar’s Bf 109 was severely hit, leav

ing the ace with no choice but to force land behind the enemy lines. Despite having both feet sprained in the violent crash, he leaped from the Messerschmitt as fast as he could, hid in some bushes, and managed to evade capture by Soviet soldiers arriving at the wreck. In a state of terror, confusion, and pain, Bar remained in hiding during the rest of the day and the following night The next morning he pulled himself together and decided to try to make it back to the German lines. Turning his leather jacket inside out, stuffing it with hay, and throw’ing away his flight boots, he attempted to appear as a Russian peasant. He could have thrown away the Knight’s Cross and the Oak Leaves he had been awarded two weeks earlier, but his vanity prevented him from doing that; he just put them in his pocket, together with his watch and his small flight pistol. Then Bar started walking with two sprained ankles. He actually made it back to the German lines. By that time he was so injured that he would remain hospitalized for two months.

On August 31, JG 53 Рік As lost its most successful pilot, the 111 Gruppe’s Leutnant Erich “Schmidtchen* Schmidt, in the Velikiye Luki area. Schmidt had achieved a total of forty-seven victories.

Oberfeldwebel Heinrich Hoffmann, another expert of IV./JG 51, achieved his fiftieth victory by downing

four "R-3s" (in reality probably R-5$ or R-Zs) in a row on September 2.4; Two days later, Hoffmann blew three Soviet aircraft— two 1)13- 3s and one MiG-3—out of the sky.4"

The mosl successful fighter unit on the Soviet side during the air battles in the Northwestern Zone in August 1941 was 39 IAL), which claimed thirty-nine German aircraft shot down that month.4′ This unit could count sev – iti lighter in’, in. n. i’t ‘iiuesvhil Ih – ing •’гг’Іііч I <- і пі.: r I К к m’v St. nrh. ikov. uiih a moil v..uv if. igiv •.iciori.- ні: r і І і he end o| Ліи;ііч:

V. Ucsh v I eyieiuni ndrey C hirkov.

GT nun and Slarviiy livu. uri lVti Гтгч. v wil l four. In V> kill.

Lum. iir a’iliv < io. ihev had ;іііі, і’чі i-lvven п. гмтіІ а:ні colic; live kilh ‘Sis l>: li"k. in. 11 In ллч. и ні ■ми-1 u I S9)." кiriian IVn Riink.. 14 I 3 і М» KI3I i.»i. k: onur, eleven mdiv i. liuil kills by the oul ■( AugiM. Rut 40.’ I lvs Mayor k. ii’si;. і r < i-i ciiyev, wiili binecr tor

On the night of September 4-5, before the advance of German ground troops forced the unit to abandon Oscl, 1 MTAP undertook its last of a total of ten Berlin missions. The twelve DB-3s of 200 BAP had also participated in nine Berlin missions, with a total of cighty – one individual flights. Fifty-five aircraft were reported to have reached the German capital. Two crashed on takeoff due to extreme overload, and the rest lost their way or suffered technical problems and had to pick nearer targets.

Of a total of eighty-six Soviet naval bombers that flew against Berlin in 1941, thirty-three were said to have reached the target. Others attacked targets of opportunity, such as Stettin, Konigshcrg, Danzig, and Schwcincmtimie. Polkovnik Preobrazhenskiy, the daring commander of 1 MTAP, and four of his pilots were awarded the Golden Star as I leroes of the Soviet Union. Five pilots of the DBA were given the same award for their participation in the Berlin raids.

The “moral bombings” of Berlin were definitely a two-edged sword. Just as these raids gave a moral boost

A fighter pilot of 13 IAP/VVS-KBF inspects some small-caliber battle damage dealt to his 1-16 during a stiff engagement with German aircraft in the fall of 1941. (Photo: Russian Aviation Research Trust.)

A fighter pilot of 13 IAP/VVS-KBF inspects some small-caliber battle damage dealt to his 1-16 during a stiff engagement with German aircraft in the fall of 1941. (Photo: Russian Aviation Research Trust.)

to the battered Soviets during these hard times, the forced abandonment of this venture was felt as a setback.

Early in September, Schlisselburg, on the southern shore of Lake Ladoga to the east of Leningrad, became the focus of ground combat in the northern combat zone. From September 5, the He Ills of Oberst Hans-Joachim Rath’s KG 4 General Wever were concentrated in heavy “rolling attacks” against Soviet fortifications in this sector. Four days later, Schlisselburg fell into German hands, depriving the defenders of Leningrad with their last land connection with their supply bases.

At this point the German Army Group North had J succeeded in driving the Soviets out of the Baltic States I and severing the land connection to Leningrad. The I defenders had suffered tremendous losses, in the air and 11 on the ground. What saved the situation for the Soviets! I on this front was that the bulk of the ground troops had j managed to withdraw in orderly fashion. Only limited I Red Army forces had been surrounded and annihilated, ] I and the construction of the Leningrad defense was in I full swing. The mobile war in this front sector had closed, j I but the Soviets had all the reason in the world to fear] the coming battle of Leningrad.

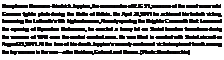

Air raids against Soviet lines of supply played a significant role in German successes in the Ukraine during the summer and early fall of 1941. According to Oberst Hermann Plocher of Fliegerkorps V, some one thousand railroad cars, many of them waiting in stations and loaded with ammunition, were destroyed during the Luftwaffe’s railroad interdiction operations east of Dneiper River. The to the left photo shows the meager remnants a Soviet ammunition train that was destroyed by German bombers during the summer of 1941. (Photo: Baeker.)

Air raids against Soviet lines of supply played a significant role in German successes in the Ukraine during the summer and early fall of 1941. According to Oberst Hermann Plocher of Fliegerkorps V, some one thousand railroad cars, many of them waiting in stations and loaded with ammunition, were destroyed during the Luftwaffe’s railroad interdiction operations east of Dneiper River. The to the left photo shows the meager remnants a Soviet ammunition train that was destroyed by German bombers during the summer of 1941. (Photo: Baeker.) Herbert Ihlefeld scored his first nine victories with the Condor Legion in Spain, and he was already one of the most successful German fighter pilots as he led l.(J)/LG 2 against the Soviet Union. From June 1941 to July 1942, Ihlefeld was one of the deadliest opponents to the aviators of VVS – Southem Front and VVS-ChF. He then served as Geschwaderkommodore in the Air Defense of Germany and ended the war commanding the first He 162 jet fighter unit. By then, he had amassed a total score of 132 victories. (Photo: Salomonson.)

Herbert Ihlefeld scored his first nine victories with the Condor Legion in Spain, and he was already one of the most successful German fighter pilots as he led l.(J)/LG 2 against the Soviet Union. From June 1941 to July 1942, Ihlefeld was one of the deadliest opponents to the aviators of VVS – Southem Front and VVS-ChF. He then served as Geschwaderkommodore in the Air Defense of Germany and ended the war commanding the first He 162 jet fighter unit. By then, he had amassed a total score of 132 victories. (Photo: Salomonson.)

(including 129 IAP, equipped with the modern MiG-3 fighters, and 61and 215 ShAP, both equipped with Il-2s) and reinforcements to 43 IAD were located close to the front.

(including 129 IAP, equipped with the modern MiG-3 fighters, and 61and 215 ShAP, both equipped with Il-2s) and reinforcements to 43 IAD were located close to the front.

That evening, the new commander of the crack 401 IAP, Mayor Konstantin Kokkinaki, appointed after Podpolkovnik Stepan Suprun’s death, led three MiG-3s on a fighter sweep over the front area. They were bounced by Bf 109s, and one MiG-3 pilot was shot down and killed while Kokkinaki and his wing man barely managed to escape with severe battle damage to their planes.

That evening, the new commander of the crack 401 IAP, Mayor Konstantin Kokkinaki, appointed after Podpolkovnik Stepan Suprun’s death, led three MiG-3s on a fighter sweep over the front area. They were bounced by Bf 109s, and one MiG-3 pilot was shot down and killed while Kokkinaki and his wing man barely managed to escape with severe battle damage to their planes.

days and nights in a rubber dinghy in the Bay of Riga before finally reaching the shore near Mikelbaka on the northern tip of the Lithuanian mainland.

days and nights in a rubber dinghy in the Bay of Riga before finally reaching the shore near Mikelbaka on the northern tip of the Lithuanian mainland.

turned around. My wingman made another attack. Once again, the Russian turned and met him head – on. Damn, this was a tough fellow!

turned around. My wingman made another attack. Once again, the Russian turned and met him head – on. Damn, this was a tough fellow!

machine-gun fire, bomb explosions, and roaring aircraft engines.*34

machine-gun fire, bomb explosions, and roaring aircraft engines.*34

To the south, on the border between Army Group North and Army Group Center, a prolonged battle was being waged at Velikiye Luki, where a Soviet counterattack was halted with the help of Fliegerkorps VHL This resulted in the complete destruction of the Soviet Twenty-second Army. Here, 40,000 Soviet soldiers perished and 30,000 were captured, a high price for merely slowing the German advance against the sector between Lake Ilmen and Moscow. Operating over this battleground, the Bf 109s of I1I./JG 53 Рік As took a heavy toll of WS-Northwestern Front, reinforced to muster 174 aircraft on August 22. On August 25, Oberfeldwebel Stefan Litjens of 111.,/JG 53 repeated Oberleutnant Erbo

To the south, on the border between Army Group North and Army Group Center, a prolonged battle was being waged at Velikiye Luki, where a Soviet counterattack was halted with the help of Fliegerkorps VHL This resulted in the complete destruction of the Soviet Twenty-second Army. Here, 40,000 Soviet soldiers perished and 30,000 were captured, a high price for merely slowing the German advance against the sector between Lake Ilmen and Moscow. Operating over this battleground, the Bf 109s of I1I./JG 53 Рік As took a heavy toll of WS-Northwestern Front, reinforced to muster 174 aircraft on August 22. On August 25, Oberfeldwebel Stefan Litjens of 111.,/JG 53 repeated Oberleutnant Erbo Graf Kageneck’s previous feat by knocking another five Soviet fighters out of the air, including four “MiG-Is” (in reality probably MiG-3s).

Graf Kageneck’s previous feat by knocking another five Soviet fighters out of the air, including four “MiG-Is” (in reality probably MiG-3s).

A fighter pilot of 13 IAP/VVS-KBF inspects some small-caliber battle damage dealt to his 1-16 during a stiff engagement with German aircraft in the fall of 1941. (Photo: Russian Aviation Research Trust.)

A fighter pilot of 13 IAP/VVS-KBF inspects some small-caliber battle damage dealt to his 1-16 during a stiff engagement with German aircraft in the fall of 1941. (Photo: Russian Aviation Research Trust.)

combat with VVS units that included 88 IAP. Among the Soviet pilots shot down was six-victory ace Leytenant Vasiliy Knyazev, who was fortunate to survive. On August 31, in the same area, Il./JG 3’s Oberfeldwebel Heinrich Brenner claimed a DB-3, followed by a “V-l 1” (probably an 11-2 of 210 ShAP). That day, also, the pilots of I1./JG 3 destroyed six Soviet aircraft in the air over the Kremenchug sector, including a TB-3 heavy bomber of 14 ТВАР shot down by the unit commander, Hauptmann Gordon Gollob (his thirty-sixth victory).

combat with VVS units that included 88 IAP. Among the Soviet pilots shot down was six-victory ace Leytenant Vasiliy Knyazev, who was fortunate to survive. On August 31, in the same area, Il./JG 3’s Oberfeldwebel Heinrich Brenner claimed a DB-3, followed by a “V-l 1” (probably an 11-2 of 210 ShAP). That day, also, the pilots of I1./JG 3 destroyed six Soviet aircraft in the air over the Kremenchug sector, including a TB-3 heavy bomber of 14 ТВАР shot down by the unit commander, Hauptmann Gordon Gollob (his thirty-sixth victory).

The l-16-equipped 69 IAP was reinforced during the Battle of Odessa by detachments from several units of VVS-ChF. including 8 IAP. This unit achieved fame throughout Soviet Union for its performance during the bitter fight for air supremacy in the late summer and autumn of 1941. This photo shows an 1-16 pilot receiving last – minute instructions from a VVS naval kapitan prior to takeoff. (Photo: Denisov.)

The l-16-equipped 69 IAP was reinforced during the Battle of Odessa by detachments from several units of VVS-ChF. including 8 IAP. This unit achieved fame throughout Soviet Union for its performance during the bitter fight for air supremacy in the late summer and autumn of 1941. This photo shows an 1-16 pilot receiving last – minute instructions from a VVS naval kapitan prior to takeoff. (Photo: Denisov.)

shot down during the Battle of Odessa22 fell victim to the fighter aces of Mayor Lev Shestakov’s 69 IAP. Lev Shestakov was credited with the destruction of eleven enemy aircraft (including eight shared victories) by mid-September 1941.

shot down during the Battle of Odessa22 fell victim to the fighter aces of Mayor Lev Shestakov’s 69 IAP. Lev Shestakov was credited with the destruction of eleven enemy aircraft (including eight shared victories) by mid-September 1941.

same area. He was in turn bounced by four Bf 109s. The Soviet pilot managed to escape in a cloudbank.

same area. He was in turn bounced by four Bf 109s. The Soviet pilot managed to escape in a cloudbank.