Prologue

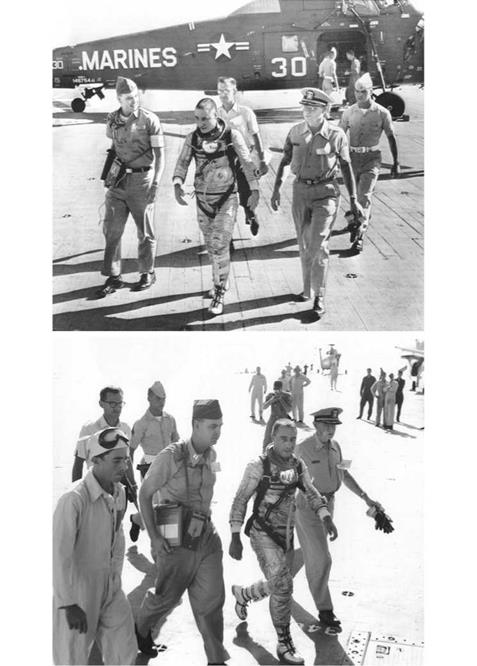

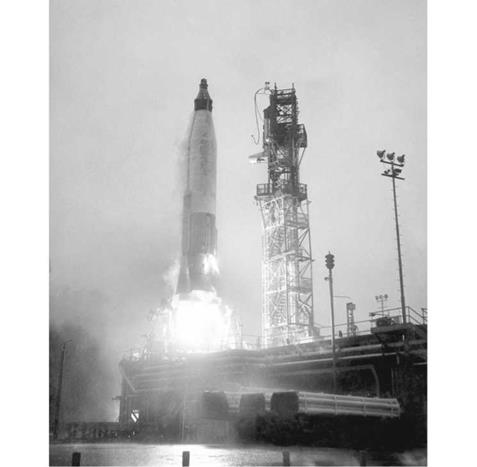

At 9:34 a. m. (Eastern Time) on 5 May 1961, the MR-3 combination of a Redstone rocket and a Mercury capsule known as Freedom 7 lifted off its launch pad at Cape Canaveral, watched by an estimated 45 million viewers across the United States. Onboard, carrying the hopes, prayers, and adoration of a nation was NASA astronaut and Navy Cdr. Alan B. Shepard, Jr. He would successfully complete a suborbital space flight lasting 15 minutes and 22 seconds. In doing so he became the second person after Yuri Gagarin to fly into space, and the first American to achieve that feat.

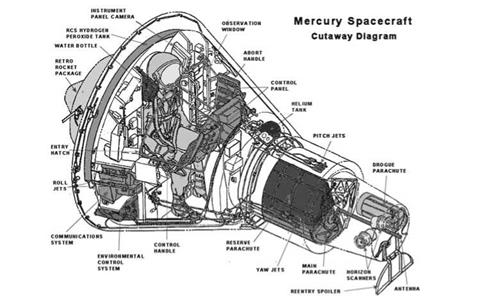

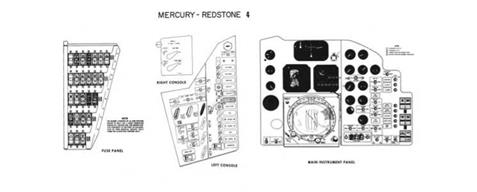

Two months later a second American astronaut would be seated aboard another spacecraft, ready to fly a similar mission to that of Shepard in order to consolidate the technical data and crucial physiological information gained from that mission. Apart from modifications to this particular Mercury capsule – as recommended by Shepard following his flight – and a far less crowded flight schedule, this second proving flight would follow basically the same test pattern as that Freedom 7.

Within those two months between the flights, however, much was happening in regard to America’s human space endeavor. Shepard’s flight had truly ignited a nation’s interest in space flight, and it was now time to capitalize on the success and projected future of NASA’s space program, which one day might lead to a human presence on the Moon.

Famously, in his second State of the Union message on 25 May 1961, just 20 days after Shepard’s history-making flight, President John F. Kennedy reported to Congress regarding the space program. “With the advice of the Vice President, who is Chairman of the National Space Council,” he began, “we have examined where we [the United States] are strong and where we are not… Now is the time to take longer strides – time for a great new American enterprise – time for this Nation to take a clearly leading role in space achievement which in many ways may hold the key to our future on Earth.”

In his speech, Kennedy set forth the concept of an accelerated space program based on the long-range national goals of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth; the early development of the Rover nuclear rocket; speeding up the use of Earth satellites for worldwide communications; and providing “at the earliest possible time a satellite system for worldwide weather observation.” An additional $549 million in funding was also requested for NASA over the new administration’s March budget requests.

At a crowded press conference held following the President’s call to Congress, NASA Administrator James E. Webb pointed out to media representatives that the long-range and difficult task of landing a man on the Moon before the end of the decade offered the United States an undeniable chance to overtake and even beat the Soviet Union to this important goal. On 7 June, during an address at George Washington University, a fired-up Webb also stated that the exploration of space was an important part of man’s “driving, relentless, insatiable search for new knowledge.”

Kennedy’s eloquent and challenging speech on 25 May had literally hinged on the success of Alan Shepard’s flight less than three weeks earlier, but now he was faced with some serious questions: would Congress embrace and not only agree to what he proposed, but supply the enormous necessary funding? The answer to both questions ultimately rested on the persuasive powers of NASA’s highly competitive administrator, who confidently felt the pursuit of funding for the agency’s programs was achievable. He had been keeping recent stock of political winds, and realized that Congress – like the rest of the nation – had been swept up in the euphoria and the opportunities offered by human space exploration, and was in what he called “a runaway mood.”

Webb’s challenge was to come up with the agency’s budget forecast figure for placing an American on the Moon by the end of the decade. According to NASA’s General Counsel Paul Dembling, the initial projections from Webb’s advisors and accountants came in at $10 billion. Dembling was there when Webb scrutinized the numbers. “He said, ‘Come on guys, you’re doing this on the basis that everything’s going to work every time, every place, no matter what you do.’ So they came back with a figure of $13 billion.”

Once again Webb studied the numbers long and hard before making his way up to Capitol Hill bearing that figure. But when he spoke to the politicians he brazenly stated that the program could cost upwards of $20 billion, and that’s what he was requesting. He had applied the old maxim of asking for too much – in this case a whopping $7 billion above the figure his analysts had arrived at – knowing that the enthusiasm of Congress for the space program might soon begin to wane. Webb was right; his ploy worked. He got approval for the money, which would ultimately prove to be very close to the mark by the time the first humans landed on the Moon.

On 22 June, NASA’s Deputy Administrator Hugh Dryden sent a letter to Robert S. Kerr, Chairman of the Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, dealing with the broad scientific and technological gains to be achieved in landing a man on the Moon and returning him to the Earth. Dr. Dryden pointed out that this difficult goal “has the highly important role of accelerating the development of space science and technology, motivating the scientists and engineers who are engaged in this effort to move forward with urgency, and integrating their efforts in a way that cannot be accomplished by a disconnected series of research investigations in several fields. It is important to realize, however, that the real values and purposes are not in the mere accomplishment of man setting foot on the Moon but rather in the great cooperative national effort in the development of science and technology which is stimulated by this goal.”

Furthermore, Dryden pointed out that “the billions of dollars required in this effort are not spent on the Moon; they are spent in the factories, workshops, and laboratories of our people for salaries, for new materials, and supplies, which in turn represent income for others… The national enterprise involved in the goal of manned lunar landing and return within this decade is an activity of critical impact on the future of this Nation as an industrial and military power, and as a leader of a free world.”

Two days after Dr. Dryden’s letter to Robert Kerr, President Kennedy assigned Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson the task of unifying the nation’s communications satellite programs, stressing urgency and the “highest priority” for the public interest.

A further two days along, on 26 June, James Webb spoke for NASA in an interview in the U. S. News and World Report, stating that “the kind of overall space effort that President Kennedy has recommended… will put us there [on the Moon] first.” This achievement, he said, costing “probably toward the $20 billion level… will be most valuable in other parts of our economy.”

The first salvos in the Space Race to the Moon had been fired. The commitment was there; the money to carry out the activities promised by the President had been made available, and the ambitious plans and goals for American space missions had the overwhelming support of the American people. Certainly the Soviet Union had shot a man into orbit, but the flight of Freedom 7 with Alan Shepard onboard had enthralled and galvanized a nation. Even though many doubted that the President’s stated goal of a man on the Moon could be achieved by the end of the decade, the will to do so was there, while the scientific and technological know-how was in place. The push to the Moon would continue.

To paraphrase the words of Alan Shepard, the first ‘baby step’ of his brief suborbital flight had amply demonstrated what was required of NASA and the nation’s astronauts, and now it was time for America to step up to the plate. There was incredible appeal and an outstanding challenge attached to the task that lay before them.

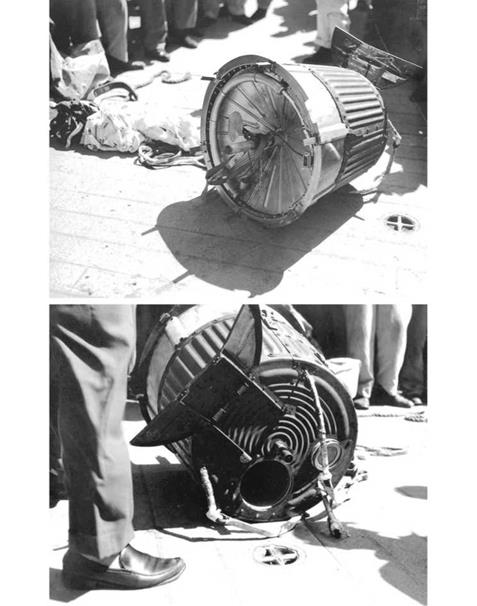

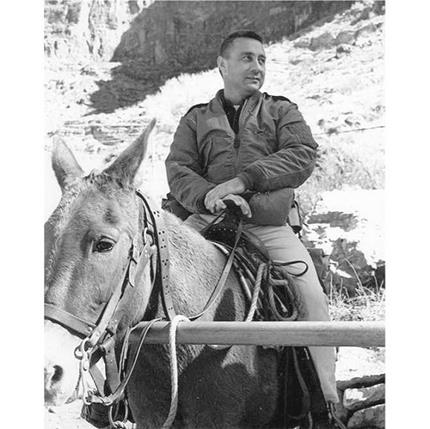

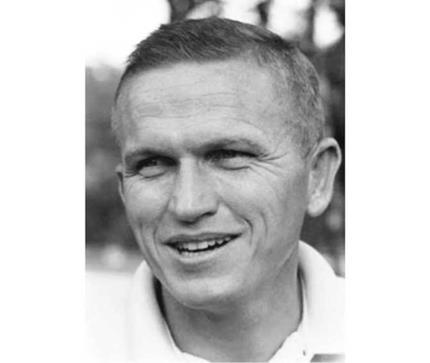

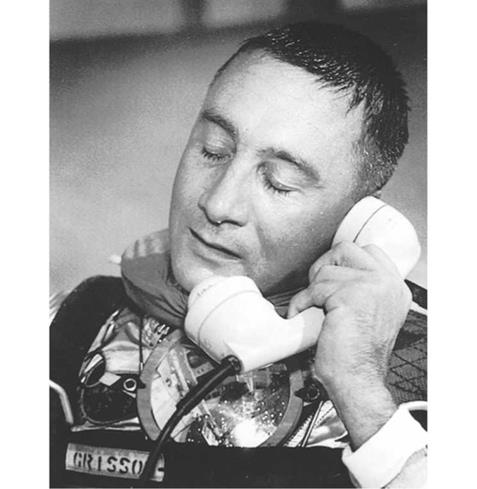

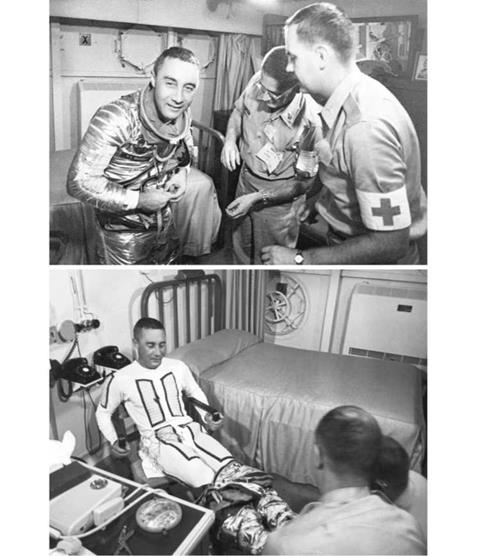

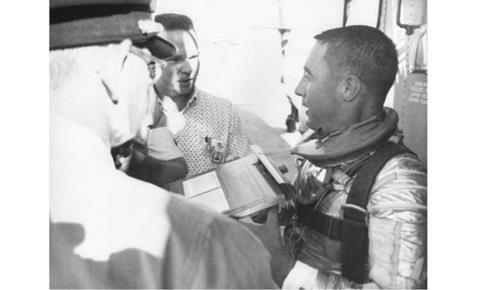

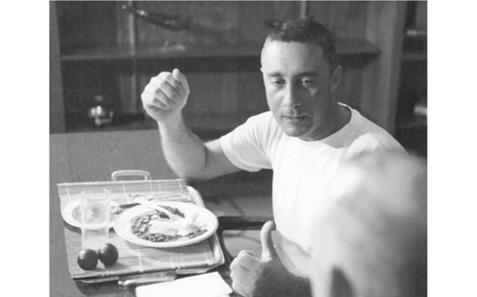

And so, on 21 July 1961, another of the nation’s finest test pilots lined up for his chance at becoming one of NASA’s renowned “star voyagers.” Strapped snugly into his contour couch aboard a spacecraft he had patriotically named Liberty Bell 7, U. S. Air Force Capt. Virgil Ivan (‘Gus’) Grissom was fully trained and ready to follow in Shepard’s pioneering footsteps in order to help to set America on a steady course to the Moon.

1