|

|

|

Technical Notes

The sub-title of this book emphasizes that this story of T. W. A. places much importance on the aircraft that it flew. As the final text went to the printer, there have been more than 1,250 of them. The Paladwr team has tried to identify and document every single one, with all the necessary details that constitute an accurate fleet record.

One of T. W.A.’s own pilots, Felix Usis ПІ, whose interests include photography and the study of ancient history (thanks partly to layovers in Cairo), devoted many hours of computer time into the preparation of the lists, drawing upon the airline’s own engineering records and, for the earlier aircraft types (long before his time) the results of research done by such historians as Ed Betts, Bill Larkins, Richard Allen, and Edward Peck. Felix supplemented his official records with additional data gleaned from various sources, including some that were not entered into the ledgers at Kansas City and St. Louis.

These lists were then meticulously checked and carefully edited by John Wegg, author and editor-publisher of Airways magazine. John is one of the world’s leading authorities on such data, and (as the saying goes) “the editor’s decision is final.” If such a presumption can be forgiven, we hope that this book will serve as a permanent and definitive reference source of all the aircraft that have flown the routes of one of the world’s great airlines.

The fleet listings are supplemented, where appropriate, with tabulations that could answer readers’ questions about the subtler differences between the variants and sub-types of some airliners. The manufacturer’s serial number (MSN) is preferred to the term constructor’s number (c/n), as in previous Paladwr Press books. Before 1949, registration numbers were NC or NX for commercial or experimental aircraft, respectively. The single N was used thereafter, and airliners already registered were re-registered when time and opportunity permitted.

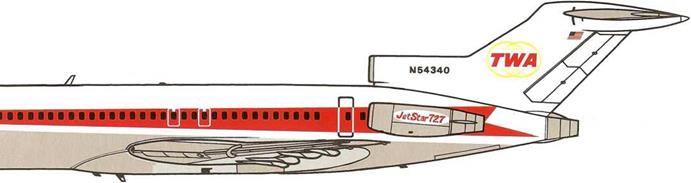

Complementing the listings and data blocks with some technical observations, artist Mike Machat has added some useful “artist’s notes” — commentaries on special features, in those cases where T. W.A.’s aircraft may have differed slightly from others of the same family.

Acknowledgements

1 hope that readers will excuse any inadvertent omissions in this customary tribute to all the folks, most of them T. W. A. veterans, who have helped me to write this book. The personal recollections of old-timers have fitted in neatly with the other inputs from various sources, official and otherwise. They have added life to the factual record, and have helped this author to reflect the personality of the airline and to appreciate the tremendous depth of loyalty that has carried them through thick and thin.

Among the printed sources, pride of place must go to Legacy of Leadership, which appears at a quick glance to be another pilots’ album of nostalgia; but on closer inspection reveals a great deal more. This is because it was compiled by a great team: Ed Betts, Dan McGrogan, and Syd Albright. I first met Syd in 1965, when visiting Western Air Lines, and he will be pleased to know that the photographs that he dug up, and the reminiscences he shared, have been recalled 35 years later. To all T. W.A. pilots, Ed is almost legendary as their historian, while Dan edited that book into shape. Ozark Airlines — Contrails was a similar compilation, obviously a labor of love by an anonymous group of Ozarkians. TWA by George Cearley, an admirable scrapbook of airline memorabilia, has also been most useful.

Most of the T. W.A. collection of photographs evaporated during the troubled times of Chapter 11-threatened 1980s, but many were either rescued or duplicated by collectors and employees. Roger Bentley’s and Jon Proctor’s collections were especially valuable, and complemented my own. They were punctuated by key contributions from Felix Usis III (including the eye-catcher on the back dust-jacket), Roger Bentley, John Malandro (master navigator), Pete Barrett and Ona Gieschen (Save-A-Connie), Bernice de Garmo (daughter-inlaw of one of the Four Horsemen), Steve Geronimo, Constance Walker, and Terry Van Dyke.

As mentioned above, countless T. W.A.-ers have been kind enough to offer contributions, and I have included as many of them as possible. They have included Andy Anderson (who flew the Stratoliner, unheated and unpressurized, during the War), Barry Craig (who tried to sponsor this very book 12 years ago), Bernice and Richard deGarmo, Tom Donahue, Lawrence Dooling, Clark Fisher, Bill Halliday, Chris Hargreaves, Gordon Hargis, F. A.Harland, Russ Hazelton, Myra Hendricks, Keith Horton, John Leamon, Henry Lotito (who flew The Thing), the aforesaid navigator, John Malandro, T. W. Meredith, John Morelli, Orville Olson, Norman Parmet, Neil Poppe, Tom Roberts, Frank Smith, Marc Spiegel, Michael Swift, Тепу Van Dyke (who helped the cows on their way), Constance Walker (whose late husband founded the Conquistadores), Susan. Warren, and Claudia Woeber.

I must not forget Jim Brown, who was the initial catalyst between T. W.A. and Paladwr Press, and Donna Knobbe, who took care of many of my needs. Above all, I thank Mark Abels, who was most generous in his Foreword, assisted tremendously in the review and fact-checking processes, and opened the doors to many valuable sources of T. W.A. lore. Together we share a respect for the English language which I hope has survived my efforts and his scrutiny without leaving too many scars.

Index

Notes: P = photograph;

T = tabulation; FL = fleet list;

N1 = map; MM = Machat drawing Major entries and "Machats" are in bold type

The maps and Machat drawings are also listed in the Contents, page 5

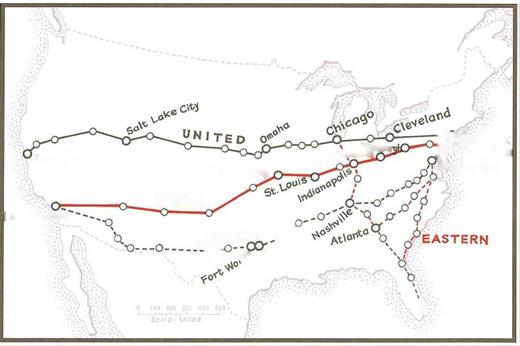

Adamson, Gary, founds Midwest Airlines, 100 ADF (Automatic Direction Finder), ploce in history, 49 Aero-car, used on TAT. air-rail service, 24, 24P, 25P Aero Corporation of Californio, 18,18P Aeromorine, pioneer airline, 8 Aerovias Brasil, T. WA affiliation, 59T Aigle Azur, French airline, buys Stratoliners, 47 Airbus A318, ordered, 104 Air Commerce Act, 1926,8 Air Express, Inc, flies express services, 37 Air Midwest, purchased by Trans State, 100 Airline Deregulation Act, 82,90 Alderman, Ralph, navigator, 49P Alexander Eaglerock, Standard Air Lines aircraft, 18P "Ambassador" service, 64 American Airlines Claim as first airline, 8 Formation, ЗО, 30M Orders Convairliner, 60

American Export Airlines, formation, Atlantic competitor, 50

American Overseas Airlines (A. O.A.), first trans-Atlantic postwar

commercial flight, 50

Army Air Corps, carries the mail, 32

Arnold, General "Hap," greets Hughes 1944,52

Atlantic Service, 50

ATR-42, commuter airline, 101ММ, 101P

ВАС – One-Eleven, competitor to DC-9,75

Bach tii-motor, West Coast aircraft, 19P

Ball, Clifford, CAM 11,8T,8M

"Bamboo Bomber," Ozark Airlines (1943), 92

Bonk of America, lends to Hughes, 73

Beech 17D Staggerwing, Ozark Airlines (1943), 92,92P, 92FL

Betts, Ed, airline historian, 26

Black-McKellor Air Mail Act, 1934,33

Boeing Air Transport, Wins air mail contract, 9,30

Boeing 40, W. A.E. aircraft, 20P,22P,22FL

Boeing 80A, United Air Unes, 30P

Boeing 95, W. A.E. aircraft, 1 IP, 20R 22P, 22FL

Boeing 204, W. A.E. aircraft, 16,16FL

Boeing 247, worid’s first modern airliner, 32,32P

Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, Tested by T. W.A. 46,46FL

Boeing 2707 SST, 74,74MM

Boeing 307 Stratoliner

First pressurized airliner, 44-45, 44P, 45MM, 45FL war effort, 46,46P, 47,47P Retired, sold, used in Vietnam,47 Compared to DC-4, Constellation, 51T Boeing 367-80,65 Boeing 707

Dominates air routes, 1958, 59 T. W.A. order, Entry into service with one aircraft, 64 Full description (-100), 65,65MM, 65P, 66P, 66FL Full description (-300), 69,69MM, 68 FL Symbolizes new его, 67P, Last T. WA. flight, 89 Boeing 717, Ordered, 104 Full description, 105,105MM, 105FL, 105P Boeing 720,69,64P, 68FL Boeing 727

Full description (-100), 75, 75MM, 75P, 76FL Full description (-200), 81,81MM, 80P, 81P, 8)FL Boeing 747

Project launched, T. WA service, 82 Full description (-100 series) 83,83MM, 83P,84P, 82FL

Index

De Havilland DH-4B, W. A.E. aircraft, 11,11FL De Havillond Comet 4 First jet airliner, 1958, 59,65 De Havilland DH-121 Trident, 75 De Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter With Ozark Air Ones, 98 Delta Air Ones Claim as first airline, 8 First order for DC-9,77 Denver Case, CAB. Route case, 64 Dickenson, Diaries, CAM 9,8T,8M Doolittle, Jimmy, returns home with T. WA Douglas M-2 (and ЛИ), WAE. aircraft, 11,11MM, 11 FI, 12P, 13P.20P

Douglas 0-38, flies Army Air Corps moil sendee, 32P Douglas B-7 bomber, flies Army Air Corps mail service, 32P Douglas DC-1

Historic prototype, 32P, 33, ЗЗР, 34P Brief history, 35 Brief description, 41

Comparison with other Douglas twins, 41MM Douglas DC-2,34P

Full description, 35, 35MM, 35FL, 35P,

Fuselage comparison with DC-3 (chart), 39 Comparison with other Douglas twins, 4ШМ Douglas DC-3

Development from DC-2,38 T. W.A. introduction (DST), 38,39MM, 39-40FL Fuselage comparison with DC-2 (chart), 39 Comparison with other Douglas twins, 4ШМ End of service, 60 Compared to post-wor airliners, 63T Ozork Air Lines (Challenger 250), 93,93MM, 93FL, 92P Freighter services, inc. wartime, 106,106P Douglas DST First version of DC-3,38 T. WA. introduction, 38,38-39FL Comparison with other Douglas twins, 41 MM Airport scene, 1930s, 42P Douglas C-47, military variant of the DC-3 Used by T. WA 38,40FL Comparison with other Douglas twins, 41 MM Douglas C-49 and C-53, military DC-3, used by T. WA, 40FL Douglas C-54

Introduction and testing, 46,46FI Delivery to T. WA, 50 Opens post-war Atlantic services, 106 First international height service, 106, 106P Douglas DC-4

Design specified by airlines, 46 Fleet list, 50T First alkargo service, 50 Entry into T. WA service, 50,51P Full description, 51,51MM Compared to Boeing 307, Constellation, 51T Douglas DC-9,76P(-31)

Ordered, 75

Fleet lists (-51,-14,-32), 76-77 DC-9-14, full description, 77,77MM, 77P DC-9-80 (see MD-80)

DC-9-30 (Ozork), 96-97,97MM, 97P, 98FL Eagle Nest Flight Center, Albuquerque, 46 Earhort, christens Ford Tr-Motor, 109P Eastern Airlines

Operates Curtiss Condor T-32,31 Chooses Martin 404,61 Economy Class, service introduced, 64 Embraer EMB145, commuter airliner, 100P Engineers

Maintain first Boeing 707,64 England-Australia Air Race, publicizes DC-2.38 Equitable Life, insurance giant Finances Boeing 707, 64 Lends to Hughes, sets up voting trust, 73 Erickson, Jeffrey, president of T. WA, 104

Ethiopian Airlines, T. W.A. affiliation, 59T

Eton Corporation, formation of T. W.A., 28

ETOPS, operations approved, 88

Fairbanks, Douglas, Jr., at T. A.T. inaugural, 24P

Fairchild C-82, full description, 56,56MM, 56P

Fairchild FH-227B (Ozark), 95,95MM, 95P, 95FL

Fairchild Metro III, with Midway/Ozark, 98,98P, 100MM

Farley, James A., Postmaster Gen, restores air mail contracts, 32

"Fashion archive," uniform collection by Clipped Wings, 48

Firestone, Harvey, at TAT. inaugural, 24

Fischer, Gerhardt, develops first radio compass, 14

Fitzgerald, Joseph, president, Ozork, 94

Flight Engineers, overtaken by technology, 49

Flint, Perry, comments on T. WA’s survival, 104

Florida Airways Corp., CAM 10,8T, 8M

Fokker F-7A (F-VII)

WAE. Aircraft, 14FL Standard Air lines, 18P West Coast Air Transport, 19P

Fokker F-10/10A, WAE. aircraft, 15,14FL, 15MM, 15P, 20P

Fokker F-14, WAE. aircraft, 20P, 22P

Fokker F-32,21,21FL, 21P,21MM

Fokker Universal, Standard Air Lines aircraft, 18P

Fokker F-27 (Ozark), 94-95,95P,95Fl

Ford, Edsel

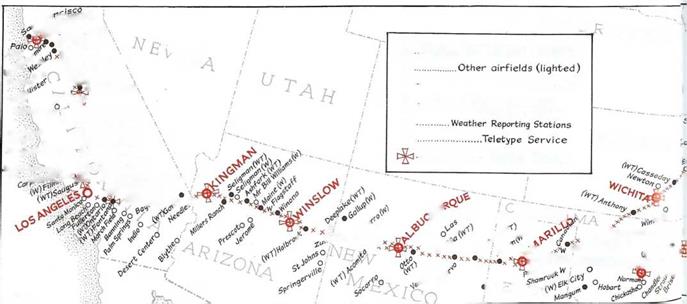

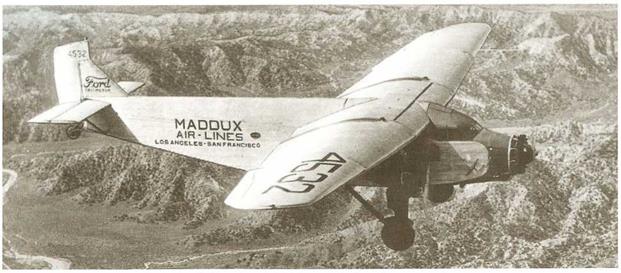

Takes interest in Stout aircraft, 23 At TAT. inaugural, 24 Ford, Henry, at T. A.T. inaugural, 24P Ford Motor Company CAM 6 and 7,8T,8M Establishes airline, 23 Ford 4-AT Tri-Motor Maddux Air Lines, 26,26P, 26FL Full description, 27, 27MM Comparison with 5-AT, 27T Ford 5-AT Tri-Motor Full description, 23,23MM, 23FL T. A.T. transcontinental inaugural, 24-25,109P Maddux Air Lines, 26FL Master plan for T. WA, 28,29P Floatplane, 44P Comparison with 4-AT, 27T Used for freight services, 106P Fortune, magazine, comments on Hughes departure, 73 "Four Horsemen," Western’s pioneer pilots, 10,1 OP Freight services, reviewed, 106 Frye, Jock

President of Standard Airlines, 18,18P

Pictured with Fokker F-32,21P

At TAT. inaugural, 24P, At Port Columbus, 25P

Career with T. WA, ЗО, 29P

Sponsors Douglas DC-1,32, ("Jock Frye letter") 33

Breaks transcontinental speed record, 33P

Partner with Howard Hughes, 42P

Flies prototype Constellation, Burbank-New York, 1944, 52,

52P, 108P

Problems with Hughes, resigns, 64 First president of los Conquistodores del Cielo, 108 Gabor, Eva and Zso Zsa, fly by T. W.A., 109P Gann, Harry, ace photographer, 12 General Ait Freight, Ford Motor, 106 Gitner, Gerald, chairman of T. WA, 104 Global affiliations, 59

GPS (Global Positioning System), aid to navigation, 49 Grace, Thomas L., president, Ozork Air Lines, 94, 94P Graham, Maurie, one of Four Horsemen, 10P Grand Canyon Airlines (1935), 98,98M Grant, Cary, flies with T. W.A., 109P Gregory, T. E.C., pictured with Fokker F-32,21P Guggenheim, Daniel, promotes Model Airway, 14 Guggenheim Fund, 14,15

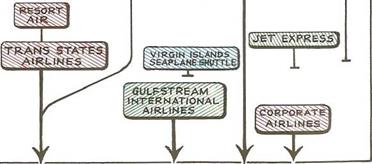

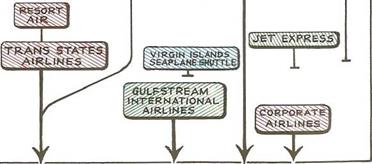

Gulfstream International, commuter airline, 100,101M Hall, Joel, founds Chautauqua Airlines, 100 Holliday, Bill, comments on post-war DC-3 services, 60 Hamilton, Laddie

Founds Ozark Airlines (1943), 92 Resigns, 94

Hamilton, Walter, Standard Air Unes, 18 Hanshue, Harris ‘Pop’

Promotes Western Air Express, 9,9P

Acquires Pacific Marine Airways, 16 Acquires Colorado Airways, 17 Acquires Standard Air Lines, 18,20 Builds W. A.E. network, 20,20M Founds Mid-Continent Air Express, 20 Pictured with Fokker F-32,21P First president of T. WA, 22,22R 28 Harland, Francis, navigator, 49 Harmon Trophy, won by Howard Hughes, 42 Hart, George, navigator, tragic death, 49 Hawaii Route Case, 82 Hawaiian Airlines, T. WA. affiliation, 59T Heathrow Airport, London, last T. WA. flight, 102 Hepburn, Audrey, flies by T. WA, 109P Hertz, John, part-owner of T. W.A., 42 Hicks, HA, member of Ford design team, 23 Hilton Hotels, purchased by T. WA, 82,90 Hiscock, Thorp, communications specialist, 14 Hoover, Herbert, Jr., WAE. communications specialist, 13P, 14 Hope, Bob, flies with T. WA, 109P Hostesses, memories, 48 Howard, William, chairman of T. WA, 104 Howell IV, Charles, founds Corporate Airlines, 100 Hughes, Howard

Brief biography, 42,42P; Buys T. WA stock 42

Break transcontinental speed record,42

Role in Atlantic service development, 50

Flies prototype Constellation, Burbank-New York, 1944,52,

52P, 108P

Interest in Bristol Britannia, 59 Prefers Martin 202 v. Convair 240, 61 Problems with Jack Frye, 64 Orders Boeing 707s and Convair 880s, 64 Problems with Convair 880,71 Surrenders ownership, 73 Icahn, Carl

Career background, takes over T. WA, 91,91P Purchases Ozark Air Ones, 91 Establishes Trans World Express, 101 Career with T. WA, and departure, 102 Agrees to method of debt payment, 104 In-Flight Movies, T. WA first, 91 INS (Inertial Navigation System) death-knell for navigators, 49 Interconf. Division (ICD), T. WA wortime operation, 46, 46M Intercontinental Hotels, acquired by T. WA, 90 Inter Urban Groin Belt Route, Parks Air Transport, 92 Iranian Airways, T. WA affiliation, 59T Irving trust, lends to Hughes, 90 James, Charles "Jimmy"

One of Four Horsemen, 1 OP, 11P With Hoover, Jr., 13P Jet Express, commuter airiine,100 Jetstream, commuter airline (see BAe Jetstream)

Jetstream, name for Lockheed L-1649A, 57 Jones, Floyd, founds Ozark Airlines, 92 Jones, Jesse, Sea. of Commerce, greets Hughes and Frye, 108 Joseph, Anthony F., founds Colorado Airways, 17 Kansas Gly Overhaul and Maintenance Bose, 107, 107P Fairfax airport flooded, 108P Kellett, autogyro, 1938,101 "Kelly" Air Mail Act, 1925,8 Kelly, Fred

One of Four Horsemen, 9P, 10P With Hoover, Jr., 13P

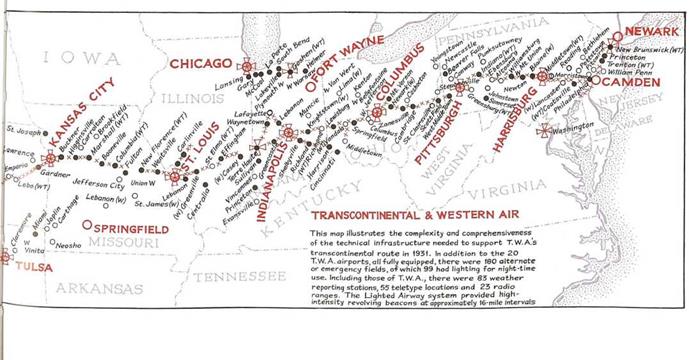

Kerkorian, Kirk, intervenes in bid for routes, 102 Keys, Clement, defines importance of ground service, 107 K. L.M. Dutch airline, DC-2 in England-Australia Air Race, 38 Koppen, Otto, member of Ford design team, 23 Kreusi, Geoffrey, develops first radio compass, 14 Larkins, Bill, airline historian, 26 Lee, John, member of Ford design team, 23 Lehman Brothers, part-owner of T. W.A., 42 Ughted Airway Ends rail-air service, 28 Place in history, 49 Lindbergh, Charles Promotes aviation, 14,107 Technical adviser to TAT., 24,24P Flies first Maddux flight, 26, 27,27P

Plans Т. А.Т. route, 28-29,29P Approves Douglas DC-1 design, 32 Influence of 1927 flight, 52 Linee Aeree Italians (L. A.I.), T. W.A. affiliation, 59T Uttlewood, Bill, recommends DC-3 design, 38 Lockheed Air Express, W. A.E. aircraft, 22 Lockheed Altair, 37FL Lockheed Vega, 37,37MM, 37FL, 37P Lockheed Orion, 37,37MM, 37FL, 37P Lockheed 14, Hughes’s round-the-wodd flight, 42 Lockheed 18 Lodestar, 50FL Lock^.,4 (Si? ..onsteiiation (and 749), 58P Compared to Boeing 307, DC-4,51T Over New York, 52P Full description, 53,53MM.53P Full fleet list, 54FL

Commentary, 59, models compared, 59T Compared to post-war airliners, 63T Lockheed 649, T. W.A. order cancelled, 59T Lockheed Super-Constellation 1049G (and 1049H), 58P Full fleet list, 55, 55AAM Commentary, 59, models compared, 59T Lockheed L-l 649A Starliner Full description, fleet list, 57, 57ЛШ, 57FL Commentary, 59, models compared, 59T Lockheed L-l Oil TriStar Full description, 87,87MM, 87P, 86P Fleet list, 86FL

L-l 011 variants compared, 87T Loening C2H Air Yacht, W. A.E. aircraft, 16P, 16FL Loewy, Raymond, designs new cheatline, 65 Lorenzo, Frank, offeers to buy T. WA, 91 Lykins, Don, flies Douglas M-2 to Washington, 12 McDonnell Douglas DC-9-82 (ММ2)

Full description, 79,79MM, 79,78R 79P, 78FL Enters T. W.A. service, 89 Ozark Air Lines, 96,97P,97FL McDonnell Douglas MD-95 (see Boeing 717)

McNary-Watres Act, 1930, 32

Maddux, Jack L., founds Maddux Air Lines, 26-27, 26P, 27P

Maddux Air Lines, 26-27

Maiden Dearborn, Stout 2-АЇ aircraft, 23

Molandro, John, navigator, 49

Marquette Air Lines, 43, 43M

Martin 202 (and 202A)

Replaces pre-war types, 47, 60, 60P Problems, 61 Preferred by Hughes, 61 Fleet list, 62FL

Compared to post-war airliners, 63T Martin 404

Full description, 63,63MM, 60P Chosen by Hughes and Rickenbacker, 61,61P Fleet list, 62-63FL Compared to post-war aidiners, 63T Ozark Air Unes, 94,94MM, 94P, 94FL Mayo, William B., directs design of Ford Tri-Motor, 23 Metro Airlines Northeast, commuter airline, 100 Metropolitan Life, sets up voting trust, 73 Mid-Continent Air Express, founded by Honshue, 20,20M Midwest Airlines

Associtoted with Ozark Air lines, 98.98P Model Airway, The, 14,14M Mohawk Airlines, trades planes with Ozork, 94 Monroe, Marilyn, flies by T. WA, 109P Moseley, Major C. C, V. P. Operations, WAE., 10P National Air and Space Museum Preserves Douglas M-4,11,12 Receives Northrop Alpha, 36 Will have Boeing 307,45 National Air Transport CAM 3,8T, 8M

Component of United Air Unes formation, 30 Navigation, history reviewed, 49 New England and Western Tpt, flies Ford floatplane, 44P New York Airways, 101 New York Helicopter, 101,101P Northrop Alpha, 36,36P.36FL Northrop Delta, 36

Northrop Gamma

Used by Tommy Tomlinson for high-altitude research, 36P, 36FL, 38,44 Northwest Airways CAM 9,8T,8M

Problems with Martin 202,61 "Ontos," (Fairchild C-82), 56 Ozork Airlines (1943), 92 Ozark Air Unes, 92-97

Begins operations, 92,92P; Map series, 96M Twin Otter service to Meigs Field, 98 Pacific Air Transport CAM 8Д8М

Component of United Air Unes formation, 30 Pacific Marine Airways, route to Avalon, 16,16M, 20M Pacific Route Case, 82 Pon American Airways Use of flying boats, 49 First Constellation service, 50 Challenged on round-theworid service, 64 Orders 707s and DC-8s, 64, Orders 747,82 Requires more range, 84 Porks Air Transport, 92

Parks, Oliver L., founds Porks Air Transport, 92

Patterson, W. R. Pat," president, United Air Unes, 30

Pennsylvania Railroad, participates in formation of T. A.T. 24-25

Philippine Air Unes, T. W.A. affiliation, 59T

Pickford, Mary, at T. A.T. inaugural, 24P

Pierson, Warren Lee, president, 1948, and 1957,64,73, 90P

Pilgrim 100A, American Airlines, 30P

Piper Twinair, 98,98M

Pittsburgh Aviation Industries Corp. (P. A.I. C.), participant in formation of T. W.A., 28

Pogue, L. Welch, chairman, C. A.B., initiates local service, 92 Polar Service, 64

Port Columbus, transfer station on T. A.T. transcontinental, 25 Portair, T. A.T. air-rail transfer station, 24,24P Ransome, J. Dawson, founds airline 101 Raymond, Arthur, designs Douglas DC-1,32 Redman, Ben, first possenger, 6P Resort Air, first name of Trans State, 99 Rhodes, Kathryn, first chief hostess, 48P Richter, Paul, Jr.

Treasurer, Standord Air Unes, 18 With TAT., 29P, Resigns, with Frye, 64 Rickenbacker, Eddie, joins Hughes in choosing Martin 404,61 Robbins, R. W.

President of T. WA, 28.29P Furloughs T. WA staff, 32 Robertson Aircraft Corp.

CAM 2,8T, 8M

Rockne, Knute, crash victim, 15 Rogers, Will, first passenger, 108,108P Roshkind, Allan, designs Martin 202,60 Roosevelt, President Cancels oir mail contracts, 32 Flies with T. WA during v/or, 46P Round-the-wodd service, 50M, 64 Rummel, Bob, tests Martin 202 ond Convair 240,61 Russell, Jane, flies with T. WA, 109P SAAB 340, commuter airliner, 99MM Ryan №1, Colorado Airways aircraft, 17P, 17FL Saudi Arabian Airlines, T. WA affiliation, 59T "SavetfConnie" organization, preserves Constellation, 59 Scheduled Air Taxi service, 98 "Secret Weapon," Constellation description, 52 Seven States Area Case, 94 "Shotgun Marriage," merger of WAE. ond T. A.T., 22 Shroeder, Major, Ford test pilot, 23 Sikorsky S-38A, W. A.E. Aircraft, 16P, 16FL Silver Wings, hostess retirement group, 48 Smith, C. R.

President, American Aidines, 30 Claims for DC-3 profitability, 38 Southern Air Transport, component of American Airways, 30 "Spoils Conferences," 32 Sportsman’s Trophy, won by Howard Hughes, 42 Standard Air Unes, pioneer airline in the v/esxt, 18,18M, 20M Stadiner, name for Lockheed L-1649A, 57

President, American Aidines, 30 Claims for DC-3 profitability, 38 Southern Air Transport, component of American Airways, 30 "Spoils Conferences," 32 Sportsman’s Trophy, won by Howard Hughes, 42 Standard Air Unes, pioneer airline in the v/esxt, 18,18M, 20M Stadiner, name for Lockheed L-1649A, 57

![]()

Tri-Jet Development

Tri-Jet Development

President, American Aidines, 30 Claims for DC-3 profitability, 38 Southern Air Transport, component of American Airways, 30 "Spoils Conferences," 32 Sportsman’s Trophy, won by Howard Hughes, 42 Standard Air Unes, pioneer airline in the v/esxt, 18,18M, 20M Stadiner, name for Lockheed L-1649A, 57

President, American Aidines, 30 Claims for DC-3 profitability, 38 Southern Air Transport, component of American Airways, 30 "Spoils Conferences," 32 Sportsman’s Trophy, won by Howard Hughes, 42 Standard Air Unes, pioneer airline in the v/esxt, 18,18M, 20M Stadiner, name for Lockheed L-1649A, 57

TWO TRANSCONTINENTAL AIR SERVICES DAILY

TWO TRANSCONTINENTAL AIR SERVICES DAILY

On 30 March 1934, the Post Office Department invited the airlines to submit new bids, and these were duly accepted by the new Postmaster General, James A. Farley, on 20 April. During the two months during which the Army carried the mail, the airlines struggled on the best they could. Drastic measures had to be taken, as the revenues from passengers and express were insignificant compared with the mail payments—effectively a life-sustaining subsidy. In the case of T. W.A., President Richard W. Robbins sent a letter to all the staff, which began: “Effective February 28th, 1934, the entire personnel of T.& W. A. is furloughed.”

On 30 March 1934, the Post Office Department invited the airlines to submit new bids, and these were duly accepted by the new Postmaster General, James A. Farley, on 20 April. During the two months during which the Army carried the mail, the airlines struggled on the best they could. Drastic measures had to be taken, as the revenues from passengers and express were insignificant compared with the mail payments—effectively a life-sustaining subsidy. In the case of T. W.A., President Richard W. Robbins sent a letter to all the staff, which began: “Effective February 28th, 1934, the entire personnel of T.& W. A. is furloughed.”

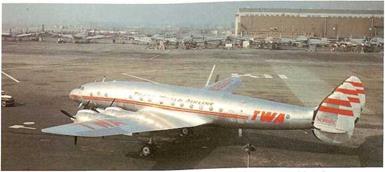

The Boeing 747, called the “Jumbo Jet” from the time it first went into service in 1970, has already served the airlines for three decades, and will probably still be in front-line flagship service for for many more years yet. This will be as long as all the generations of airliners before 1970, at least from the debut of the first DC-3. Its reign covers half of the proverbial three-score years and ten—quite a lifetime. When they started service, the 747s cost $21 million each. Now, a Series -400 would cost about $140 million.

The Boeing 747, called the “Jumbo Jet” from the time it first went into service in 1970, has already served the airlines for three decades, and will probably still be in front-line flagship service for for many more years yet. This will be as long as all the generations of airliners before 1970, at least from the debut of the first DC-3. Its reign covers half of the proverbial three-score years and ten—quite a lifetime. When they started service, the 747s cost $21 million each. Now, a Series -400 would cost about $140 million.