RENDEZVOUS!

Gemini VI-A’s launch on 15 December was precisely timed so that its Titan would insert it into an orbital plane which closely coincided with that of Borman and Lovell. Trajectory planners had calculated that a liftoff 6.471 seconds past 8:37 am provided ideal conditions for a rendezvous during their fourth orbit. The Gemini VII crew saw only cloud when they tried to spot the launch, but once the Titan climbed out of the weather Borman and Lovell had an oblique view of its contrail from their vantage point out over the Atlantic.

From within the capsule, however, Schirra and Stafford’s rise from Earth was dramatic. In his autobiography, Stafford would recount feeling little discomfort as G forces climbed beyond five, then seven, peaking at nearly eight, and his first view of the planet’s horizon as the Titan’s second stage inserted them into a preliminary orbit. The G loads caused him to feel some pain in his gut and pressure on his lungs, forcing him to take short, sharp breaths – then, all at once, five minutes and 35 seconds after launch, the forces went from eight down to zero. The two men raised their visors, took off their gloves and finally removed their helmets, stowing them below their knees.

Six hours of work awaited them. At orbital insertion, they were trailing Gemini VII by almost 2,000 km. An hour and a half after launch, Schirra pulsed the OAMS thrusters to increase the apogee to 272 km and close the distance to some 1,175 km; this was followed at 10:55 am by a ‘phase-adjustment’ burn, whose purpose was twofold. Firstly, it reduced the distance between them and the target and secondly, it raised Gemini VI-A’s perigee to 224 km. Most importantly, it established the timing for the subsequent chase. Half an hour later, Schirra turned the spacecraft 90 degrees to the ‘right’ – in a southward direction – and again fired the OAMS to push Gemini VI-A into the same plane as Borman and Lovell. By this point, three hours after launch and entering their third orbit, they had narrowed their distance still further to 483 km. At 11:52 am, Capcom Elliot See told them that they should soon be able to establish radar contact with Gemini VII. Indeed, a flickering signal was replaced by a solid lock at a range of 434 km.

A little under four hours into the flight, in the so-called Normal Slow Rate (NSR) manoeuvre of the rendezvous sequence, Schirra pulsed the aft-mounted thrusters for 54 seconds to slightly increase Gemini VI-A’s speed and enter an orbital path of 270 x 274 km, co-elliptic with and fixed 27 km below the target, which was now 319 km ahead. Stafford, meanwhile, busied himself with a circular slide rule and heavily-crosshatched plotting chart on his lap, checking the computer’s analysis of the radar data and relaying information to Mission Control. Shortly thereafter, they placed their spacecraft in the ‘computer’ – or automatic – rendezvous mode and Schirra dimmed the interior lights to aid his visibility. At 1:41 pm, he announced his first visual sighting of what he thought was a star: ‘‘My gosh, there is a real bright star out there. That must be Sirius.’’ It wasn’t. It was Gemini VII, glinting in the sunlight, just 100 km away. They lost sight of it briefly when it entered Earth’s shadow, but when their eyes adjusted they identified its blue tracking lights. Twelve minutes later, when the target was 60 km ahead and the geometry was correct, Schirra initiated the terminal phase manoeuvre designed to close the range to 3 km. He then executed a pair of mid-course correction burns and, at 2:27 pm, just 900 m from their target, started pulsing Gemini VI-A’s forward thrusters to steadily reduce the closure rate.

Closer and closer they drifted, until Schirra and Stafford were just 40 m from Borman and Lovell, with no relative motion between them. Back on Earth, in the MOCR, flight controllers erupted in applause and waved small American flags, while Chris Kraft, Bob Gilruth and other senior managers fired up celebratory cigars. Unlike Vostoks 3 and 4, which had merely drifted past each other at a distance of several kilometres as a result of being in slightly different orbits in August 1962, Wally Schirra had achieved a ‘real’ rendezvous. He defined it thus: ‘‘I don’t think rendezvous is over until you are stopped – completely stopped – with no relative motion between the two vehicles, at a range of approximately 120 feet [40 m]. That’s rendezvous!’’

At one point during the rendezvous Stafford had been confused, however. After being rivetted to his plotting board, he suddenly looked up, glanced out his window, and saw randomly moving stars. Thinking Schirra had lost control, he barked out that they had blown it. Quickly, however, Schirra reassured him that the ‘stars’ were not stars, but merely John Glenn’s fireflies: frozen particles reflecting sunlight. The two men laughed. (Later in the mission, using fast ASA 4000 film in a Hasselblad,

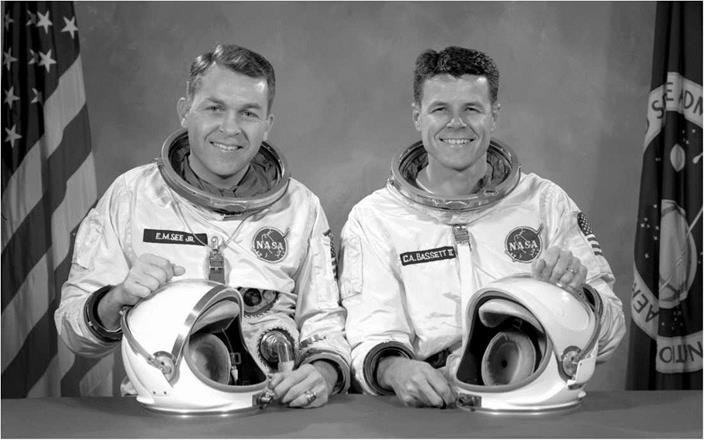

|

Gemini VII in space, as seen by Schirra and Stafford. |

they engaged in astronomical photography for one of the principal investigators, Jocelyn Gill. However, not all of the images were astronomical; some were urine dumps and when they returned to Earth, Gill looked at one beautiful constellation of ‘stars’ and asked them what it was. Without missing a beat, Schirra looked at the shimmering cloud of just-dumped urine droplets and deadpanned: ‘‘Jocelyn, that’s the constellation Urion!’’)

From their vantage point in the ‘passive’ spacecraft, Borman and Lovell had expressed fascination at the thruster bursts and spurts emerging from Gemini VI-A. At one stage, they were startled to see a tongue-like jet some 12 m in length! Both crews would report cords and stringers 3-5 m long streaming and flapping behind their respective spacecraft; these turned out to be the remains of covers from the shaped explosives which severed the Geminis from the final stage of their respective Titan Ils. The rendezvous had cost Schirra barely 51 kg of fuel and only 38 per cent had been expended in total from Gemini VI-A’s tanks, leaving him plenty in reserve to fly a tour of inspection of, and station-keep with, Gemini VII for the next five hours and three orbits. At one stage, Schirra manoeuvred as close as 30 cm, allowing he and Stafford to hold up a ‘Beat Army’ card in their window to torment Borman, a West Point graduate. In response, Borman held up a ‘Beat Navy’ card. Gemini VI-A moved to the rear of its sister craft to examine the stringers, then came nose-to-nose, and so stable were both Geminis that, for a time, neither command pilot had to even touch his controls.

During manoeuvres, Schirra found the spacecraft responded crisply, allowing him to make velocity inputs as low as 3 cm per second, which he and Stafford concluded were fine enough to execute a docking with an Agena-D or any other target. ‘‘I took my turns flying,’’ recounted Stafford, ‘‘having convinced the Gemini programme managers to add a second manoeuvre controller to the pilot’s side.’’ As the crews’ workday drew to a close, Schirra flipped Gemini VI-A into a blunt-end-forward orientation and pulsed the OAMS thrusters to separate. After a meal and sleep, Schirra awoke to a stuffy head and runny nose, which made him glad that the mission was flexible and, assuming all of the tasks were completed, had the option to return to Earth after 24 hours. Moreover, Gemini VII’s fuel cells needed the attention of mission controllers and would benefit from having the additional tracking burden of Gemini VI-A out of the way.

But not before a final ‘gotcha’ from Schirra and Stafford. It was nine days before Christmas, after all…

As the two spacecraft went their separate ways, the MOCR controllers and Borman and Lovell were initially alarmed to hear Stafford report that he saw ‘‘an object, looks like a satellite, going from north to south, probably in polar orbit… Looks like he might be going to re-enter soon. Stand by one. You just might let me try to pick up that thing.’’ Then, over the communications circuit, came the sound of the Gemini VI-A astronauts playing ‘Jingle Bells’. The ‘object’, it seemed, was the familiar, jolly, red-suited, white-bearded old man himself, making his annual ‘reentry’ to deliver his payload of presents to terrestrial children. ‘‘You’re too much!’’ radioed Capcom Elliot See.

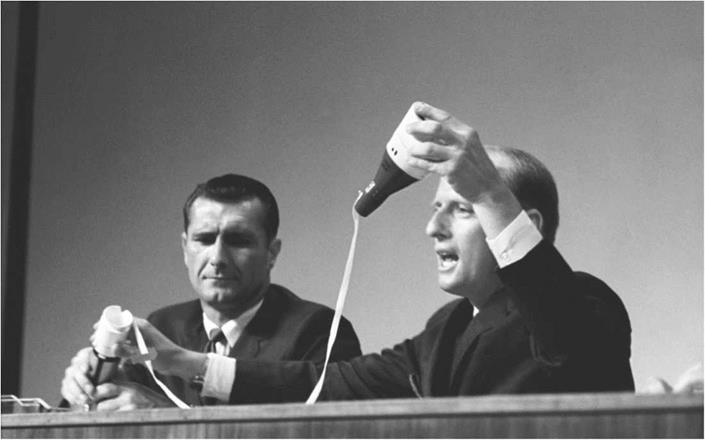

In fact, Mickey Kapp, producer of Bill Dana’s ‘Jose Jimenez in Orbit’ album, had

provided Schirra with a small, four-hole Hohner harmonica just days before launch. Schirra had secured it in one of the pockets of his space suit with dental floss. “I could play eight notes,” he wrote, “enough for ‘Jingle Bells’. It may not have been a virtuoso performance, but it earned me a card in the musicians’ union of Orlando.’’ (Schirra would also receive a tiny gold harmonica from the Italian National Union of Mouth Organists and Harmonica Musicians.) Not to be outdone, Francis Slaughter of the Cape’s Flight Crew Operations Office, had fitted small bells to the boots of Stafford’s suit… supposedly as a joke, but little realising they would provide backing rhythm for Schirra’s Christmas soiree. Today, the tiny harmonica and Stafford’s bells are enshrined in the Smithsonian.

A little more than a day after launch, Schirra placed his spacecraft into an inverted, ‘heads-down’, attitude, to provide better observation of Earth’s horizon. At an altitude of ЇОО km, to ensure that Gemini VI-A did not overshoot its splashdown point, he set its banking angle at 55 degrees left and held it steady until the computer took control at 85 km above the ground. ‘‘We were going backwards, heads-down,” wrote Stafford, ‘‘so I had a great view of the horizon and the cloud-covered Gulf of Mexico, and a clear sense that we were really moving fast.’’ The astronauts duly switched off the computer at 24 km, deployed the drogue parachute at 14 km and the main canopy blossomed out at З.2 km. Impact with the Atlantic, in the first successful demonstration of a controlled re-entry, took place at 10:28:50 am on 16 December, at 2З degrees З5 minutes North latitude and 67 degrees 50 minutes West longitude, merely 1З km from its pre-planned splashdown point. It was fortunate that it was so successful, for Gemini VI-A’s descent was in full view of live television beamed from the recovery ship Wasp, transmitted via the Early Bird communications satellite. An hour later, displaying a thumbs-up of a job well done, Schirra, then Stafford, strode down the Wasp’s red carpet to the strains of a band playing ‘Anchors Aweigh’.

For Borman and Lovell, almost three days awaited them before their own splashdown. They started by removing their suits. The novelty of being in space had now worn very thin and, years later, Borman would describe the time after Gemini VI-A’s departure as ‘‘a tough three days’’ in which the two bearded, exhausted and uncomfortable men ‘‘simply existed… in a very, very cramped space’’. At the suggestion of Cooper and Conrad, they had taken novels. Borman spent some time reading Mark Twain’s ‘Roughing It’, which proved apt, and Lovell dived into part of ‘Drums Along The Mohawk’ by Walter D. Edmonds, a text about the American pioneers.

Even Mike Collins, who served as Lovell’s backup on Gemini VII, wondered how they managed to endure it. In his autobiography, Collins admitted the Gemini was so small that, on the ground, he could not sit in the simulator for more than three hours at a time and even with the relative freedom of weightlessness – which allowed Borman and Lovell to float, restore circulation and avoid bedsores – it was an uncomfortable existence. ‘‘The cockpit was tiny, the two windows were tiny, the pressure suits were big and bulky and there were a million items of loose equipment which constantly had to be stowed and restowed,’’ he wrote, adding that ‘‘no one who has never seen a Gemini can fully appreciate what it’s like being locked inside one for two weeks.’’

As the mission wore on, the Post Office passed up a request for them to mail their Christmas cards and parcels early. Lovell complained that he had “a stack of stuff up here”, to which the capcom replied that he should have sent his presents home with Gemini VI-A. With their homecoming looming, they were reminded by Chuck Berry to elevate their feet and pump their legs, to which Borman announced that they were eager to get out of Gemini VII as soon as possible.

Retrofire, described graphically by Lovell, commenced as they flew over the Canton Islands on their 206th orbit. “Retrofire has a unique apprehension in the fact that both of us are aviators and we understand the apprehension in flying,” he said. “If you have an accident in an airplane, something’s going to happen: you hit something or it blows up. Now, in liftoff and re-entry, a space vehicle is like an airplane. Something’s happening. But if the rockets fail to retro, if they fail to go off, nothing’s going to happen. You just sit up there and that’s it. Nothing happens at all. That’s the unique type of apprehension, because you know that you’ve gotten rid of the adaptor, you know that you’re going to have 24 hours of oxygen, ten hours of batteries and very little water. So you play all sorts of tricks to get those retros to fire.’’

Fortunately, the four retrorockets fired in tandem and to perfection. As their descent commenced, Capcom Elliot See told them to fly a 35-degree left bank until Gemini VII’s computer guidance assumed control. “You have no control over how close you’re going to get to the target,’’ Lovell recalled later. “Your only control is how good that computer is doing or how good your [centre of gravity] was when you set up the computer and the retrofire time.’’ Borman rolled Gemini VII into a heads – down orientation, allowing him to use the horizon as an attitude guide, but could see nothing and was forced to rely upon his instruments and Lovell’s called-out adjustments. After the flight, Borman would endorse the need for two pilots to fly a Gemini, since there was no practical way to follow the instruments and monitor the horizon at the same time.

The dynamic loads after 330 hours in weightlessness came, they recounted, “like a ton’’, even though G forces reached a peak of 3.9, barely half as much as a typical Mercury re-entry. Drogue parachute deployment jolted the two men, rocking the spacecraft by 20 degrees to either side, after which the main canopy opened. When Gemini VII hit the ocean at 9:05 am, Borman, unable to see any recovery helicopters, felt that he had lost a bet with Wally Schirra – that he could land the closest to his planned impact point. In reality, he had landed just 11.8 km off-target. In view of their lengthy stay in space, the two men were surprisingly fit, although Borman felt a little dizzy and both walked with a slight stoop on the deck of the recovery ship, Wasp. “The most miraculous thing,’’ reported a jubilant Chuck Berry, “was when they could get out of the spacecraft and not flop on their faces; and they could go up into the helicopter and get out on the carrier deck and walk pretty well.’’ They were, added Berry, in better physical condition than Cooper and Conrad had been. Lovell’s cardiovascular cuff revealed that less blood pooled in his legs than Borman and both maintained their total blood volumes.

As Chris Kraft and his flight control team fired up more cigars on the afternoon of 18 December 1965, the prospects for a lunar landing before the end of the decade had grown steadily brighter. Alexei Leonov’s triumphant spacewalk in March had been followed by the United States’ decisive response: no fewer than five Gemini missions – ten men blasted aloft, in total – whose endurance records had shown that astronauts could survive two-week flights to the Moon and back with few physical or psychological problems. They could rendezvous and survive the rigours of working outside their spacecraft in pressurised suits… or so it seemed. The next year, 1966, would see five more flights, closing out the programme in advance of the first Apollo mission, and all were destined to push the envelope still further by physically docking Geminis onto Agena-D targets and having astronauts spacewalk from craft to craft to install and remove experiments.

It would be an ultimately successful, though risky, year. Indeed, Deke Slayton would describe it as “NASA’s best’’. However, it would begin inauspiciously. In its third month, aboard Gemini VIII, the man who would someday be first to set foot on the Moon almost became one of the first to die in space. In its sixth month, the man who would one day be the last Apollo astronaut to set foot on the Moon would come close to losing his own life as the dangers of EVA became terrifyingly clear. Before that, on the gloomy, overcast morning of 28 February 1966, fire and death would rain down over St Louis, Missouri.