As the proverb says; necessity is the mother of invention – and perhaps appositely, as the German Chancellor put it in the Reichstag on 4 August 1914, attempting to justify the infringement of Belgian neutrality, ‘Necessity knows no law’ – so it was the French, with huge tracts of their northern and north eastern territory serving as advanced German airfields, who saw the need to stop German reconnaissance over-flights. Let there be no doubt, even before the war had largely ground to a halt after the first few weeks, the French were given plenty of first-hand evidence of how good German reconnaissance was. Furthermore, they, themselves, had similarly benefit – ted from the input of their own airborne reconnaissance in halting the first major German push aimed towards Paris. With their typical no-nonsense approach to problems, the French put a machine gun into a number of their two seaters and sent them off to shoot down the

German two seaters as expeditiously as possible. Indeed, a Taube proved to be the first victim of this advance, falling to the nose-mounted gun of an armed Voisin on 5 October 1914. The fighter had been born and all this long before the close of 1914.

There were, however, problems with many of these first generation fighters, especially those with a tractor, or nose-mounted engine, prime among which, it was soon discovered, being their inability to fire with any accuracy. Actually, this was a far more fundamental problem than many realised, centred on the fact that the pilot now had to do much more work to fly the aeroplane towards his target in such a manner as to provide his observer with a free field of fire and anticipate enemy evasion; this happening between machines of fairly evenly matched performance. Further, while the Cauldron, Farman and Voisin pusher-engined two seaters appeared to eliminate

the problem by giving the nose gunner an unlimited forward field of fire, the inherent drawbacks of added weight and drag that went with the pusher layout reduced speed and agility significantly. Thus, unless a pusher had an initial height advantage, enabling it to dive on its prey, it was unlikely ever to be able to close on the enemy. As the French saw it, what was needed was to remove the observer altogether and simply fix the gun where the pilot could reach it. Oh, and while doing this, why not fix the gun so that it could fire directly ahead through the propeller arc of a small, fast single seater, of which the French had many? The concept certainly had appeal, chief of which was the single seater’s significant speed advantage and, therefore ability to close quickly.

the problem by giving the nose gunner an unlimited forward field of fire, the inherent drawbacks of added weight and drag that went with the pusher layout reduced speed and agility significantly. Thus, unless a pusher had an initial height advantage, enabling it to dive on its prey, it was unlikely ever to be able to close on the enemy. As the French saw it, what was needed was to remove the observer altogether and simply fix the gun where the pilot could reach it. Oh, and while doing this, why not fix the gun so that it could fire directly ahead through the propeller arc of a small, fast single seater, of which the French had many? The concept certainly had appeal, chief of which was the single seater’s significant speed advantage and, therefore ability to close quickly.

The problem now was to solve the business of firing a machine gun through the propeller without shooting its blades off. In this regard, a Swiss engineer had already patented a gun synchronization system in 1913 and Frenchman Paul Saulnier of Morane-Saulnier fame had started working on a similiar device prior to the outbreak of war, but while both systems looked fine on paper, neither of them wanted to work in practice. Clearly logic,

even of the French variety, had it limits. Pursuing ‘Plan B’, France turned to one of her most lauded aviators, Roland Garros. Maybe he could come up with a solution. After a few months he did. What he produced was far from ideal, but it worked. Garros and his mechanic, tired of trying to get the ‘fidgety’ Saulnier synchronizer to work, turned to Panard, the armoured vehicle builders, who knew a bit about armour cladding. Garros’s solution was simple, why bother doing anything complicated, just clad the propeller blades with armoured cuffs and, hey presto, the bullets that did strike the cuff would be deflected while the rest sped off in the enemy’s direction. To everyone’s delight, when Garros and his mechanic tried this in early April 1915 it worked and this deflector system was widely employed on Morane-Saulnier Type Ns until the interrupter or synchronizer systems could be made to work. The really great bonus of simply having to point the aeroplane at the enemy and fire the gun was to reduce pilot workload back to almost the point it had been before the gun had made its advent. The first real fighter had been produced.

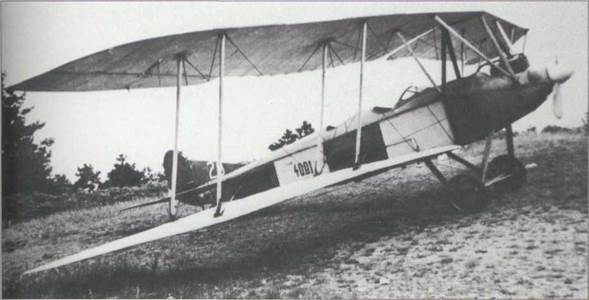

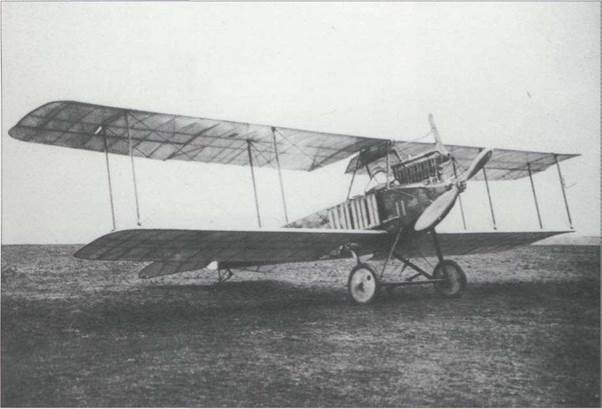

The deployment of these French single seat fighters gave them a significant tactical advantage over their German opponents, but only temporarily. On 18 April 1915 Roland Garros was compelled to land behind enemy lines and was captured before he could destroy his machine with its armour-cuffed propeller blade secret. While the Germans were not necessarily overly impressed by this less than elegant solution, they did see the merit of allowing the pilot to aim the whole aircraft at his prey. Anthony Fokker, who was already working on a gun interruptor system was induced to expedite completion. This he did in May 1915, fitting the equipment into one of his Fokker M5K reconnaissance two seaters. On 1 August 1915, Max Immelmann brought down a BE 2c over Douai using the Fokker interrupter gear in a Fokker Eindecker, taking the first step towards redressing the balance in the tactical airwar. A number of Fokker M5Ks were converted to gun-equipped E 1s and by the end of August 1915, the era of the so-called Fokker Scourge had begun. From September 1915, the somewhat underpowered E Is with their 80hp Oberursal rotaries, were augmented by the 100hp rotary powered E IIs and E IIIs, the last of the Eindeckers, the 160hp engined E IV emerging in January 1916. The belligerents on both sides now had effective single seat fighters, It was now up to men like Boelcke and Immelmann to define and refine the tactics of aerial combat. From this point on and for the rest of the war, fighter development continued apace, with one side or the other gaining temporary superiority with the introduction of their latest type, only to find it rendered obsolescent long before its successor could possibly be brought into service.

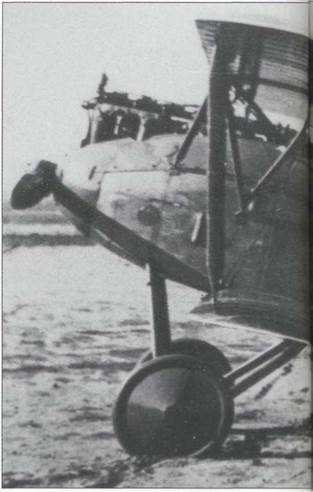

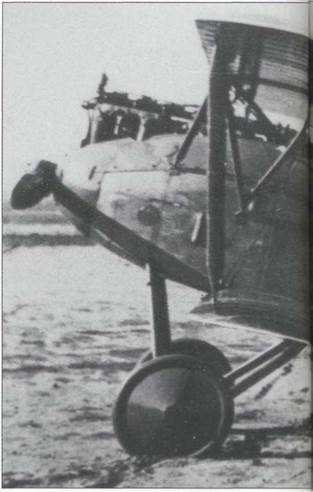

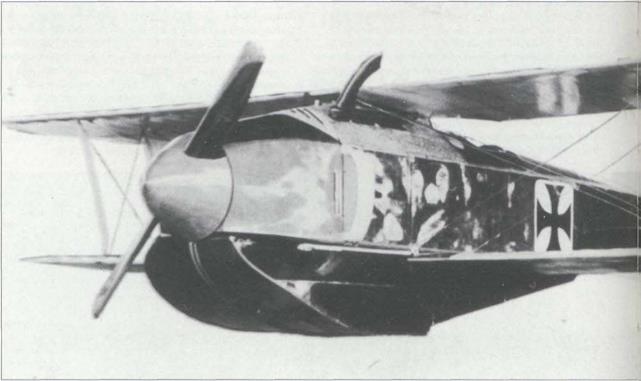

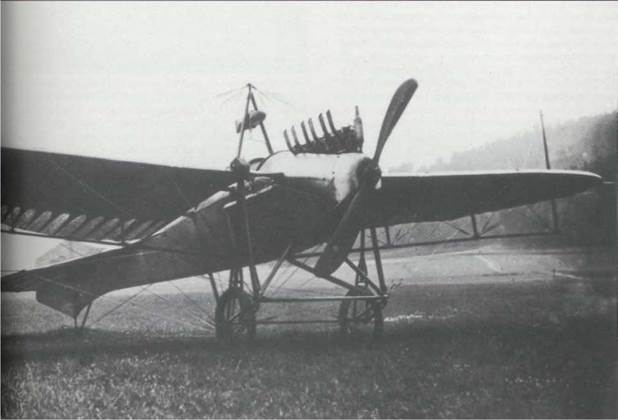

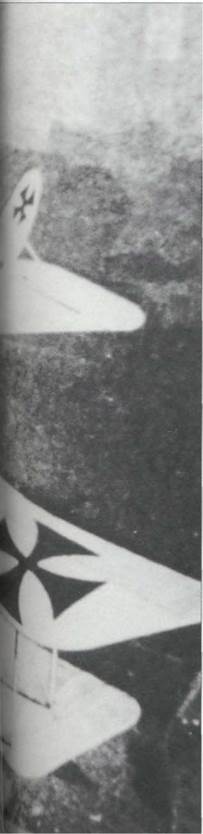

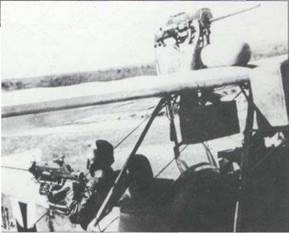

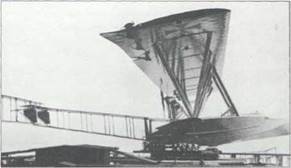

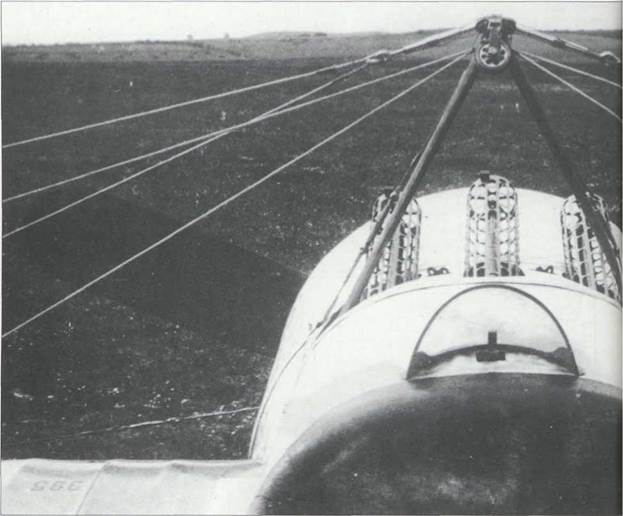

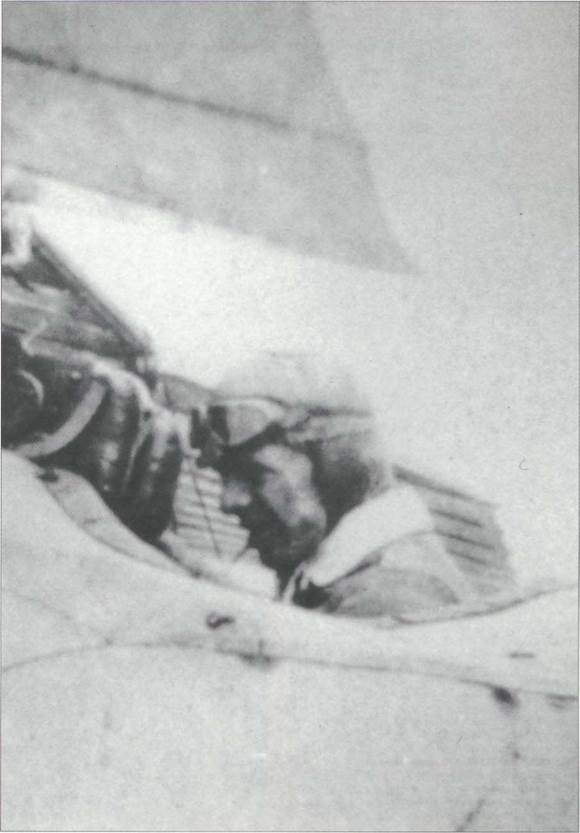

A near to pilot’s-eye view of an experimental triple 7.92mm Spandau gun installation synchronized to fire through the propeller arc of this Fokker E IV. This fit was the culmination of Fokker’s efforts to arm his early monoplanes, or eindeckers and although Max Immelmann tested this three-weapon fit, he preferred the Eindecker’s standard single gun installation. (Cowin Collection)

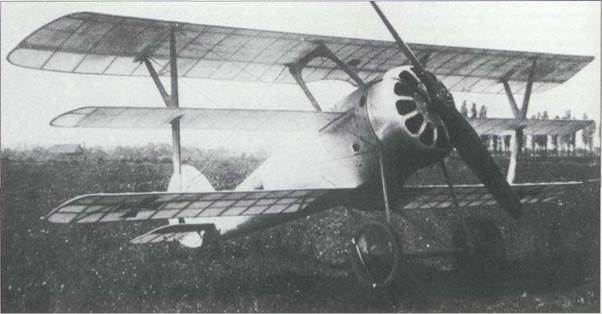

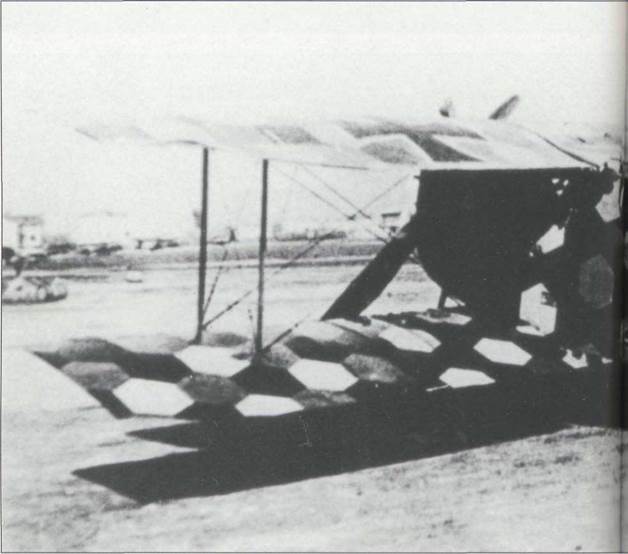

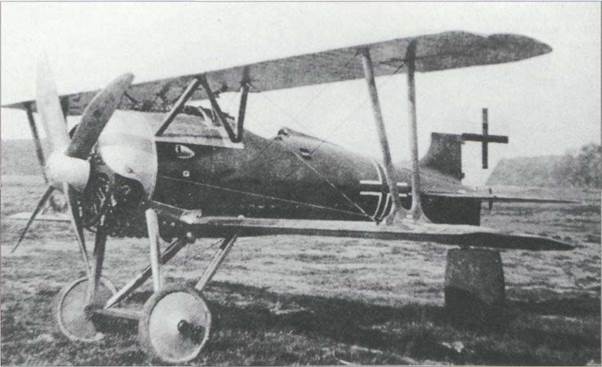

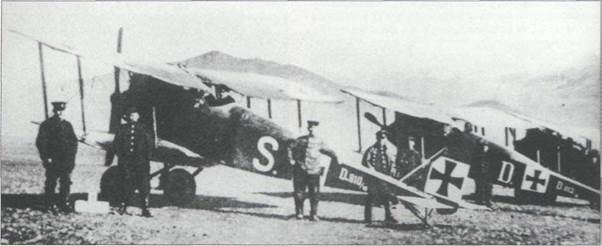

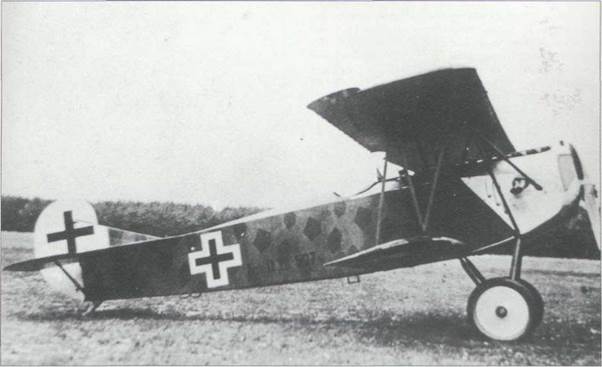

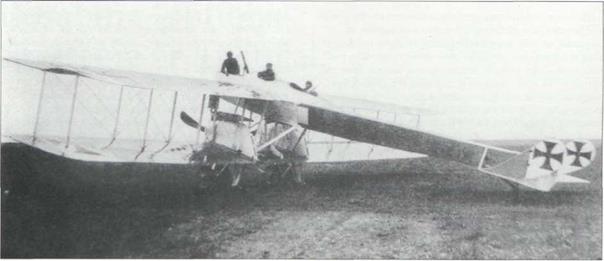

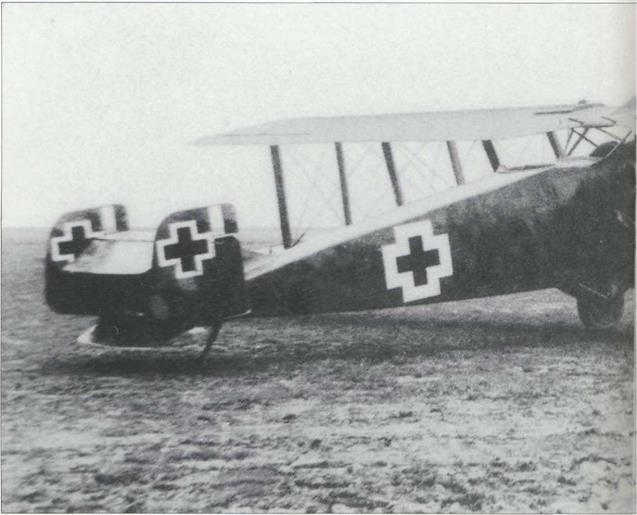

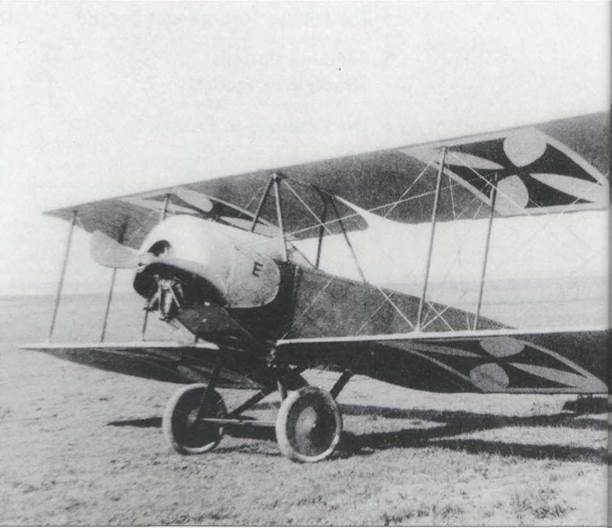

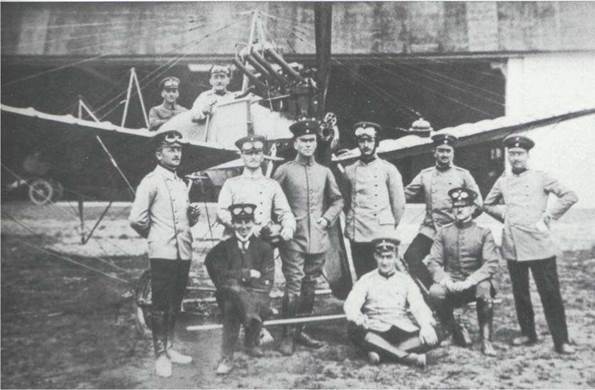

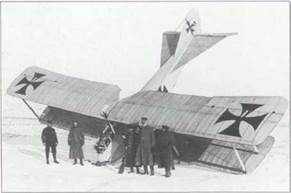

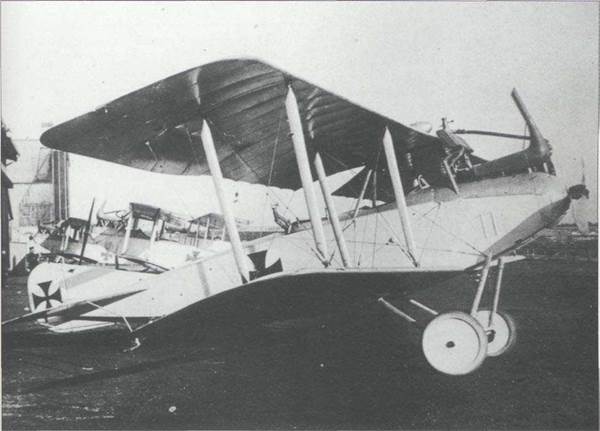

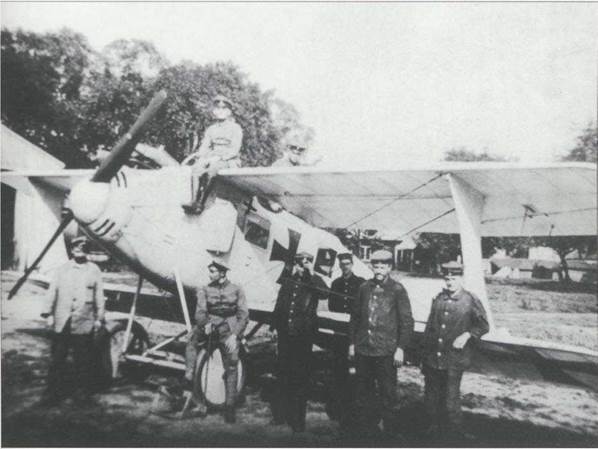

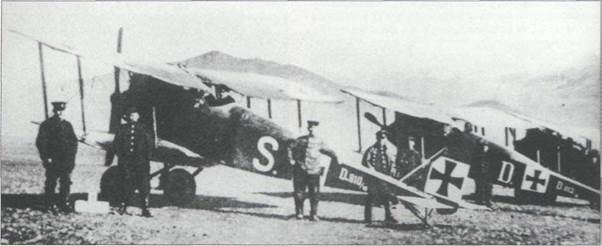

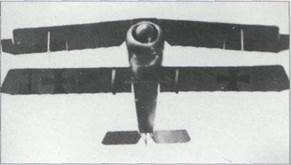

Fokker E Ills of KEK Vouziers, the KEK signifying KampfEinsitzer Kommando, comprising 16 aircraft, in this case, supporting the 3rd Army in the Vouzier sector. Initially the relatively few Fokker Eindeckers had been distributed in pairs to the Field Flight Sections, but were brought together to form the KEK from February 1916. However the KEK proved shortlived, being ended in October 1916, to make way for the squadron, or Jagstaffel system, which, while theoretically having 16 machines, frequently could only muster around 8. The Jagstaffel, usually abbreviated to Jasta, was to remain the basic fighter unit of the German army until the Armistice, although after mid-1917, these were operated more and more as part of a larger wing, or Jagdeschwader, normally shortened to JG, that comprised anything up to 60 aircraft. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

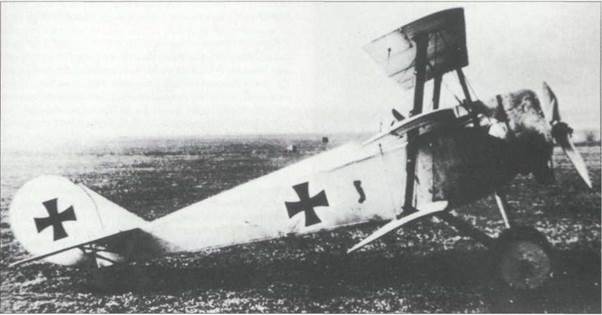

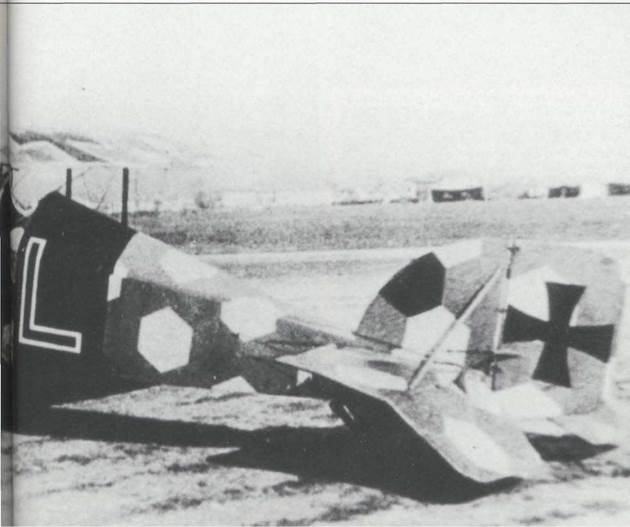

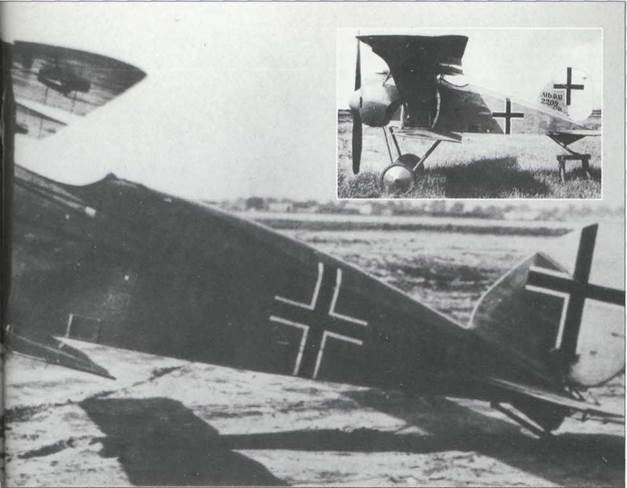

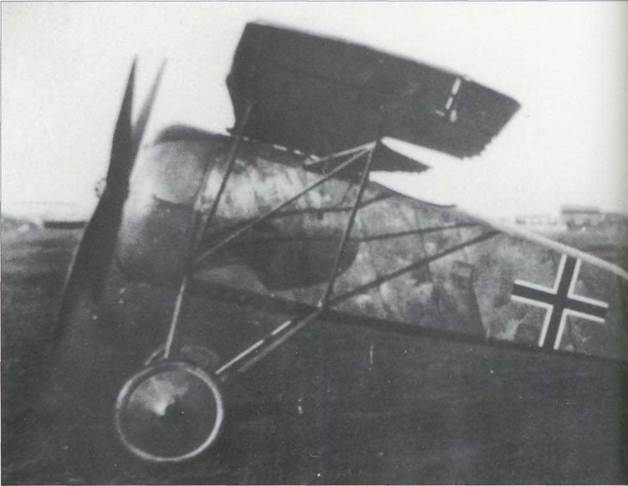

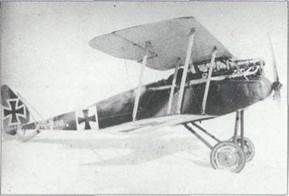

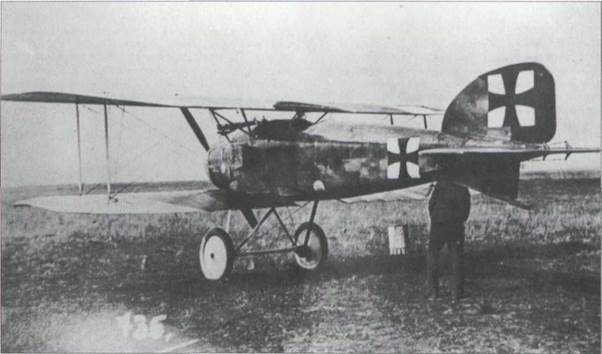

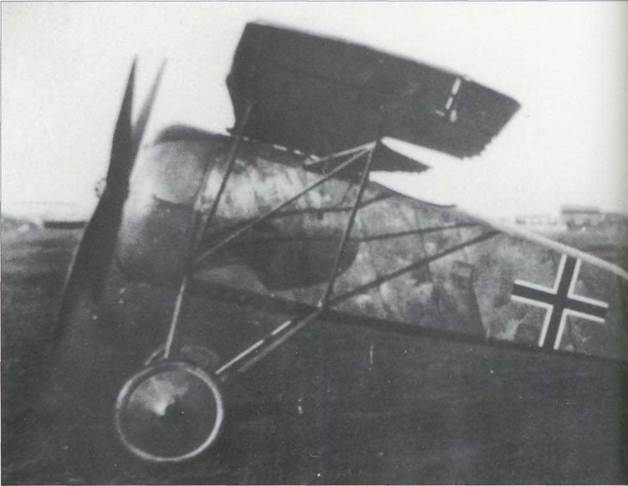

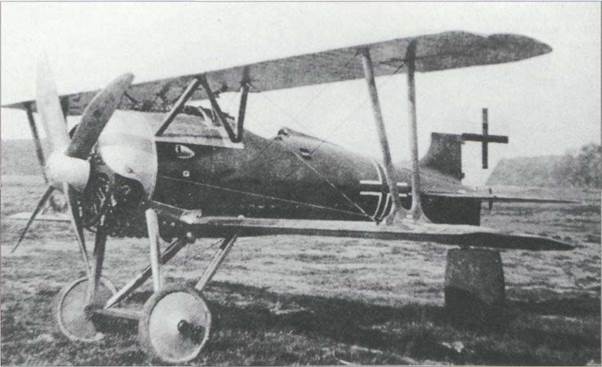

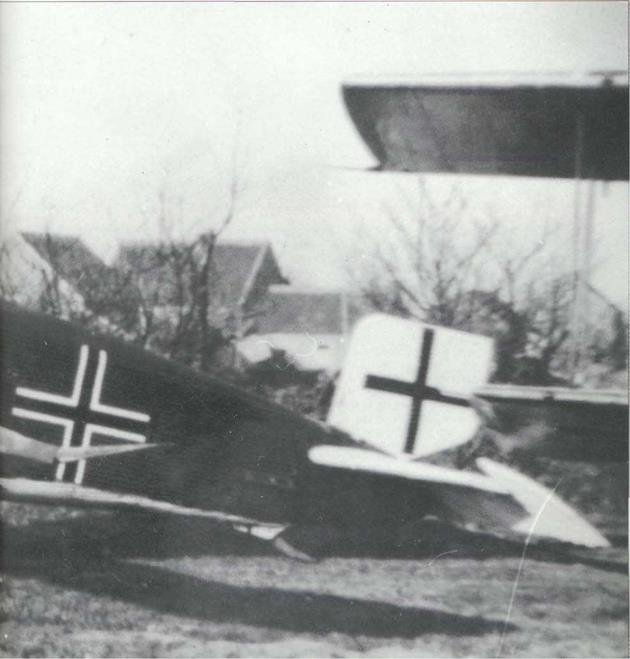

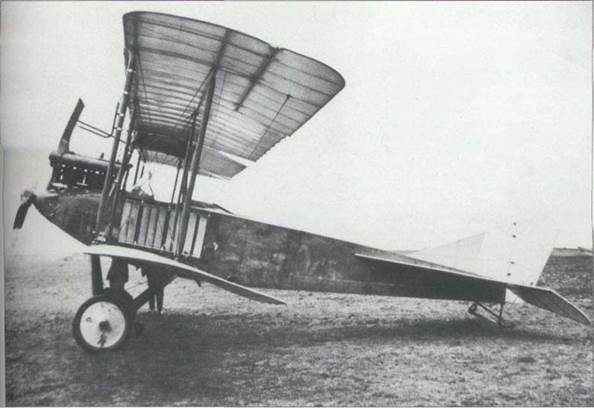

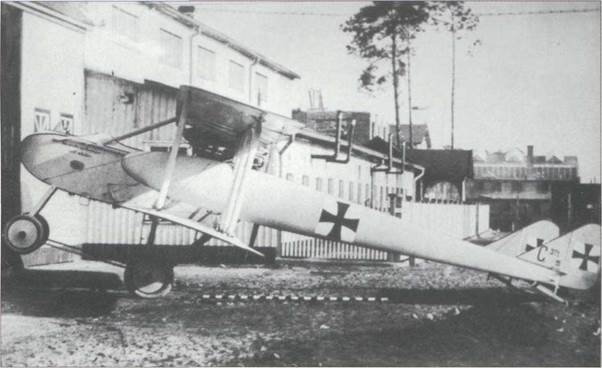

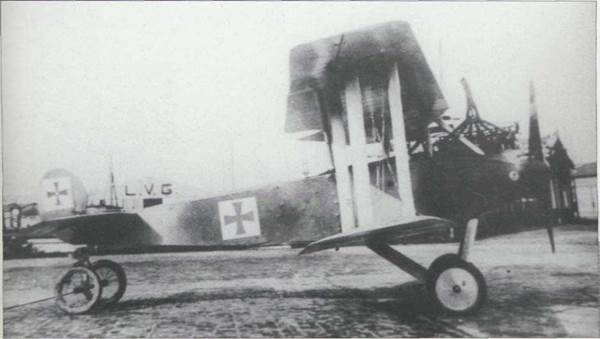

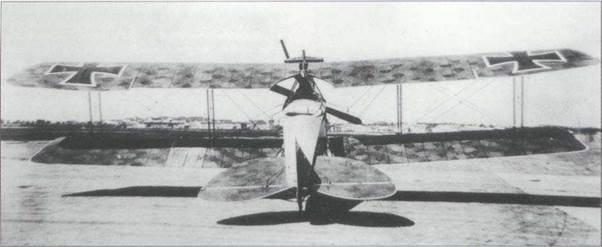

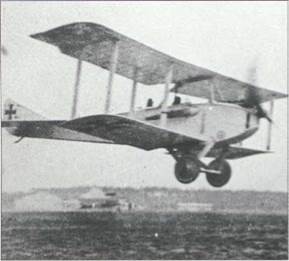

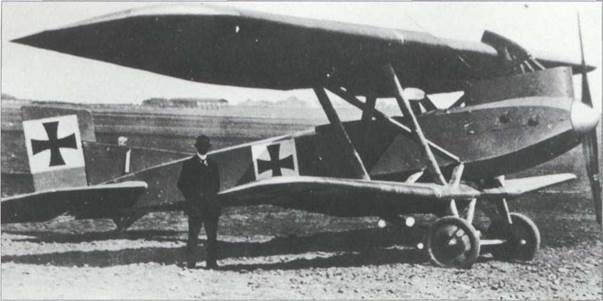

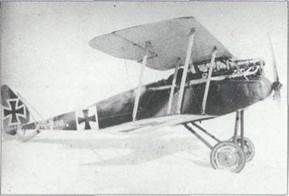

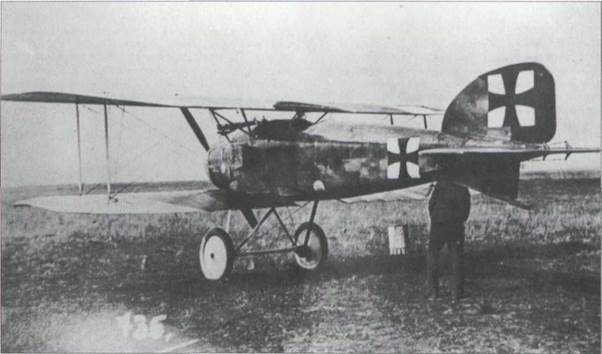

The Fokker E III of Max Immelmann at Douai, where his unit, KEK 3, was based. Immelmann had been the first to score a victory in a Fokker Eindecker in the autumn of 1915, when he and Oswald Boelcke were serving together as the single seater section of Fl Abt 62. Inventor of the Immelmann Turn, a basic air fighting maneuvre using a loop and roll to reverse the enemy’s initial advantage if attacked from the rear, Oblt Max Immelmann, with 15 confirmed victories, was killed in air combat near Lens on 18 June 1916. Powered by a 100hp Oberursel U I rotary, the E III had a top level speed of 87mph at sea level. Armament normally comprised a single 7.92mm Parabellum or Spandau, although some E Ills were known to carry a second. Around 260 E Ills are believed to have been built. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

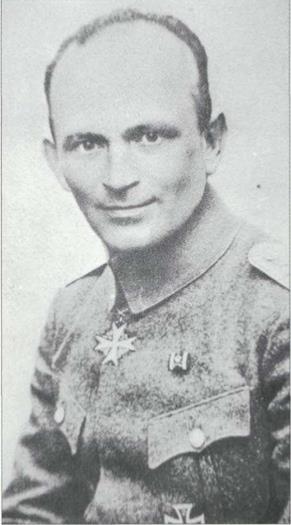

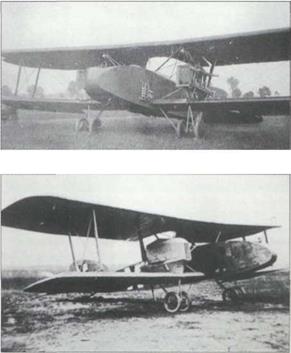

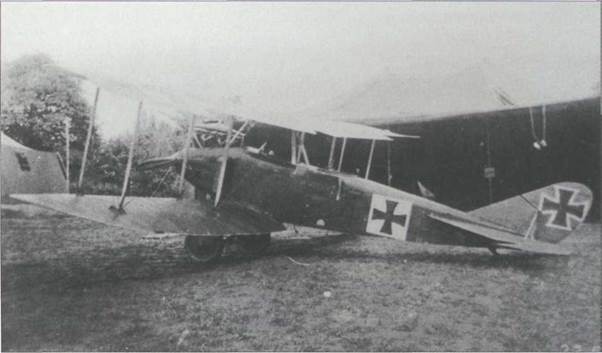

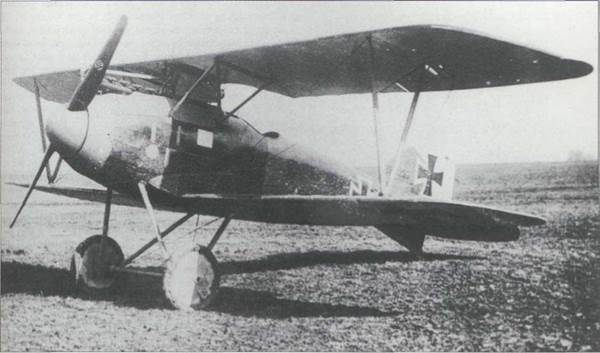

Kurt Student, like Boelcke and Immelmann, first came to the attention of his superiors thanks to his prowess flying a Fokker E III. Transferred with their E Ills to the Russian Front in September 1915, Student and his companion soon found themselves unopposed whenever and wherever they flew. Later, Lt 44 Student was to take command of Jasta 9 in 1917, staying as its leader until the Armistice, by which time he held the rank of Oberleutnant, or 1st lieutenant and had a confirmed score of 5 ‘kills’. Student went on to command the German aiborne forces in World War II, a responsibility vested in the German air force, unlike its American and British opponents, whose armies retained full control of both glider and paratroop assets. Student is depicted here sitting in his Albatros D III soon after taking over Jasta 9. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

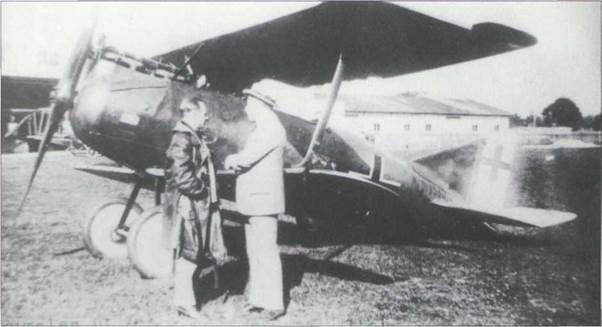

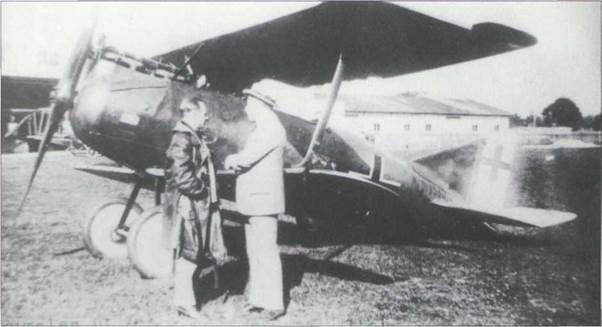

Anthony Fokker, seen here with his mother, in 1919, after his return to Holland. Fokker had built his first design, the Spin, towards the close of 1910, test hopping it and simultaneously making his first flight prior to Christmas. While away, a colleague wrecked this machine, but, undaunted, Fokker, with help, built a second Spin, this time with a rudder. It was in this aircraft that he gained his pilot’s licence in May 1911. The jovial Fokker, born on 6 April 1890, soon proved to have more than his fair share of business acumen, one of his early shrewd moves being to leave his native Holland, at the close of 1911, to set up shop in Germany. Once there, his tireless self-promotion, supported by his not inconsiderably aerial bravado, helped keep his name and products prominent. Never one to miss an opportunity, his early military flying school venture brought not only much needed cash, but longer term influence in high places. Later, during the war, Fokker, some of whose designs were not held in the highest esteem, frequently held lavish entertainments for senior military staff on the top floor of

|

|

Berlin"s Hotel Bristol which he appears to have leased on a long term basis. In yet another example of his business initiative, Fokker, in the immediate wake of the Armistice, managed to commandeer a train and smuggle much of his plant’s machine tools and a number of Fokker D VII airframes and engines across the neutral Dutch border. Fokker died on 23 December 1939. (Cowin Collection)

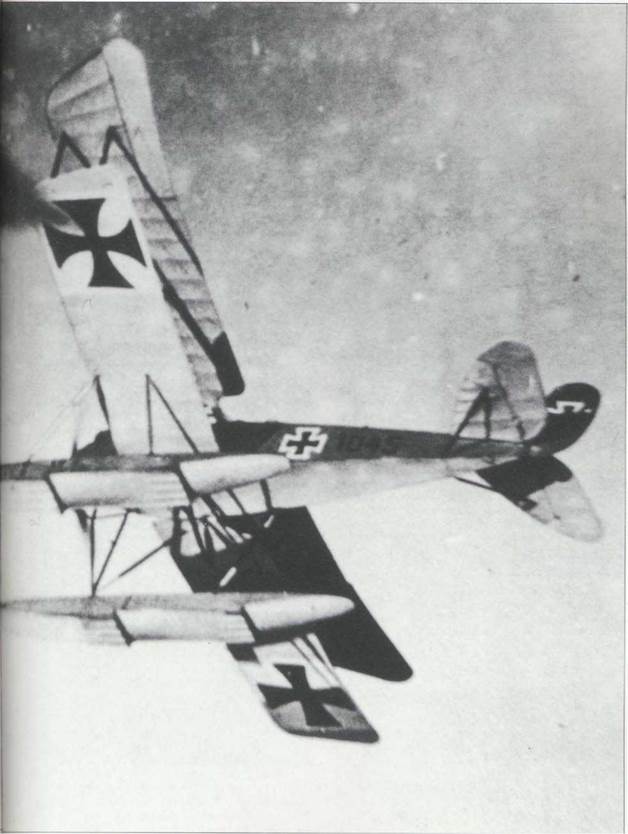

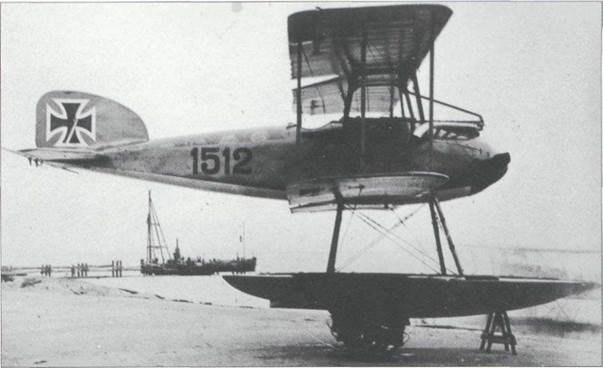

carried additional outboard ‘V wing struts. Deliveries of the approximately 200 D Is built began in the autumn of 1916 through early 1917, while deliveries of the 58 naval KDWs stretched from September 1916 to February 19l8.The prototype, shown here in its initial form, has a fin that differs from those of production aircraft. (Cowin Collection)

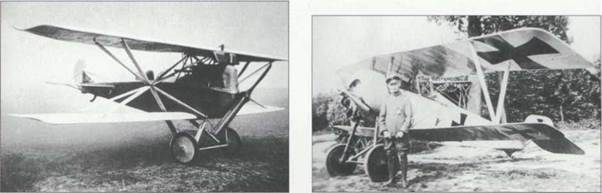

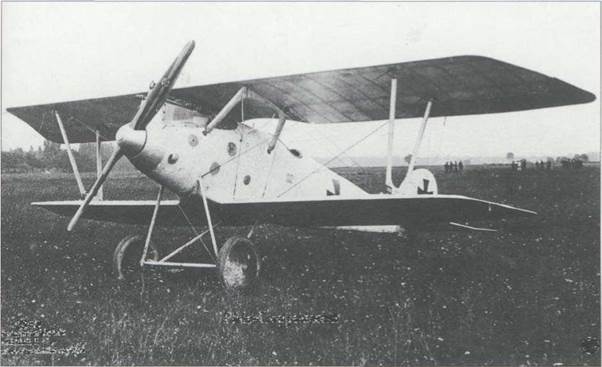

The joint brainchild of the Steffen Brothers, Franz and Bruno, the Siemens-Schuckert Werke D 5 single seat fighter was completed in the autumn of 1915, but progressed no further than the prototype stage. Visible in the background is the same company’s E I prototype, a developed version of which killed designer/pilot Franz Steffen in June 1916. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

The Fokker Scourge that had lasted nine months or so came to an end in the late spring of 1916, with the mass advent of the fast and agile Nieuport 17, for which the Eindeckers were no match. As was inevitable, an intact example of the Nieuport fell into German hands fairly soon after its debut. The German reaction was interesting. As quickly as possible the aircraft was stripped and engineering drawings produced. These, along with requests for tenders to produce a copy were issued to industry. Euler and Siemens-Schuckert Werke were the two companies selected to build this back-engineered version of the Nieuport. Depicted here is a line-up of five Siemens – Schuckert Werke D Is, fresh from final assembly, at the company’s Nuremburg facility. Markedly inferior in performance to the original, the single seat D I used a 110hp Siemens Sh I rotary, giving a top level speed of 97mph at 6,560 feet. Originally, orders for 250 D Is had been placed with the firm, but these were progressively cut back to 94 by the spring of 1917.The D I was mainly delivered to the Eastern Front, being generally considered inferior to the newly developed Albatros D III. (Cowin Collection)

The Hansa-Brandenburg KD, with its novel interplane strut layout earned the instant sobriquet of ‘Star Strutter’. Completed at the start of 1916, the KD was Ernst Heinkel’s first single seat fighter design. Small and rugged, the KD was soon selected by the Austrians to serve as their standard fighter. The D I, to give its Austrian designation, was built locally by Phonix and Ufag. Powered initially by a 160hp Austro-Daimler, later Ufag machines had a 185hp Austro-Daimler, giving the compact fighter an enviable top level speed of 116mph, along with an excellent initial rate of climb in excess of 1,100 feet per minute. One of the D I weaknesses centred on it single 8mm Schwarzlose machine gun’s lack of reliability, the gun being mounted above the upper wing centre-section to fire clear of the propeller arc and, thus not reduce its rate of fire. Besides siring the D I, the KD went on to be bought by the German navy as the KDW floatplane fighter. In this guise, the machine

The Hansa-Brandenburg KD, with its novel interplane strut layout earned the instant sobriquet of ‘Star Strutter’. Completed at the start of 1916, the KD was Ernst Heinkel’s first single seat fighter design. Small and rugged, the KD was soon selected by the Austrians to serve as their standard fighter. The D I, to give its Austrian designation, was built locally by Phonix and Ufag. Powered initially by a 160hp Austro-Daimler, later Ufag machines had a 185hp Austro-Daimler, giving the compact fighter an enviable top level speed of 116mph, along with an excellent initial rate of climb in excess of 1,100 feet per minute. One of the D I weaknesses centred on it single 8mm Schwarzlose machine gun’s lack of reliability, the gun being mounted above the upper wing centre-section to fire clear of the propeller arc and, thus not reduce its rate of fire. Besides siring the D I, the KD went on to be bought by the German navy as the KDW floatplane fighter. In this guise, the machine

|

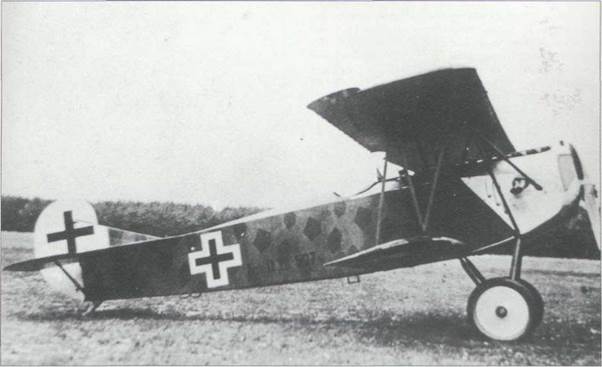

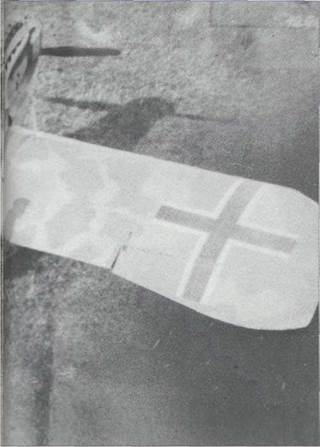

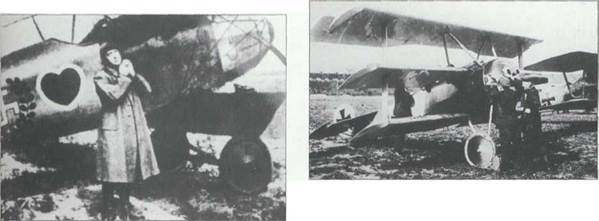

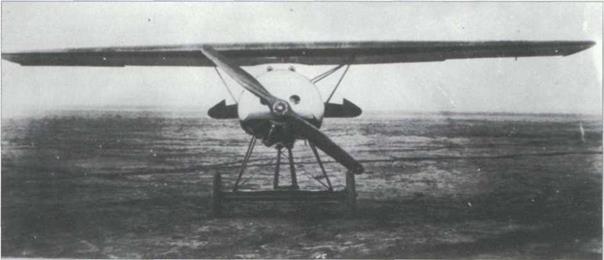

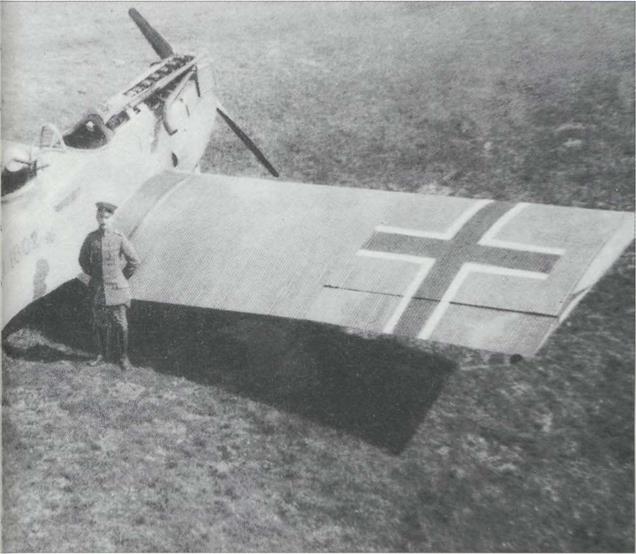

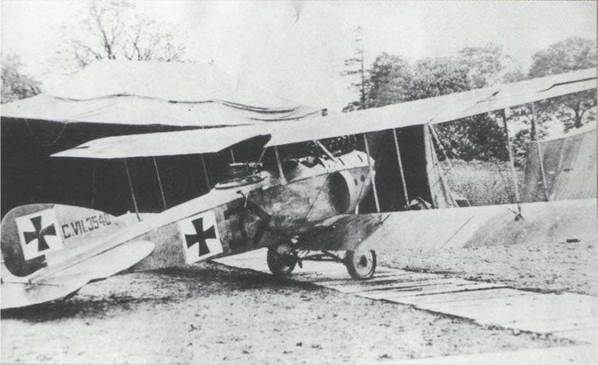

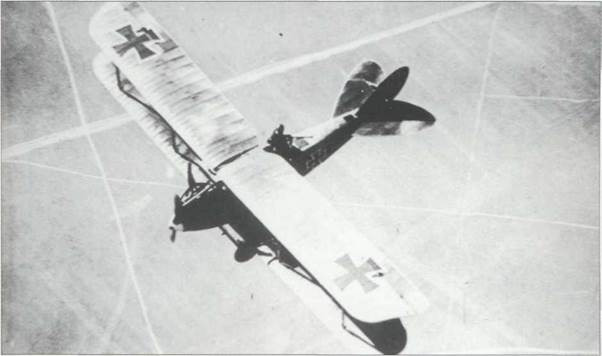

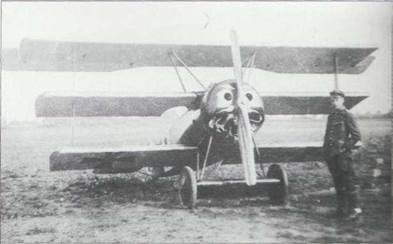

Very few records survive concerning the other Nieuport copy, the Euler D. I, other than the knowledge that it was powered by a 100hp rotary and, as this picture shows, that at least one

|

|

made it to the Western Front. This image was taken in July 1916 or immediately thereafter with KEK Nord, prior to it becoming Jasta I on 23 August 1916. The Euler’s pilot, seen here, Lt Leffers, credited with one ‘kill’, was to meet his own end near Cherisy on 27 December 1916. (Cowin Collection)

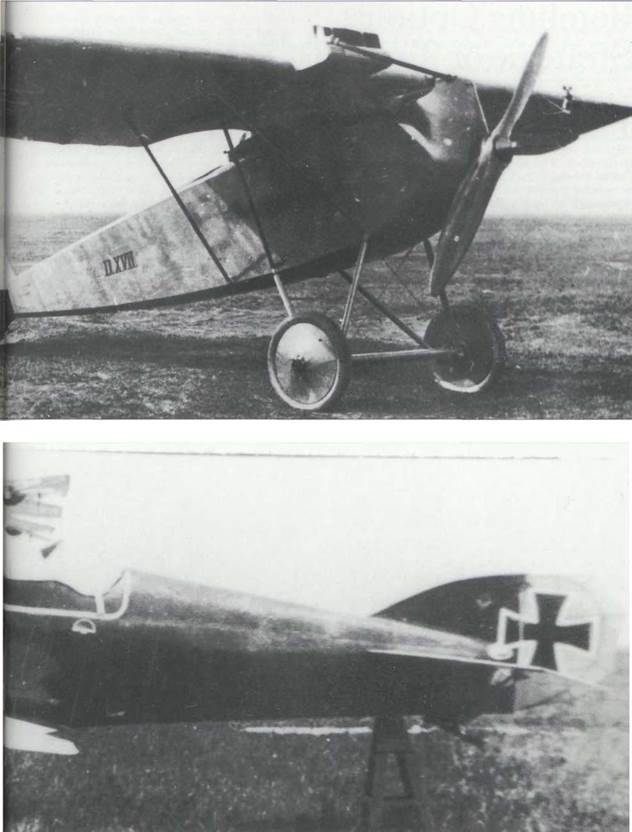

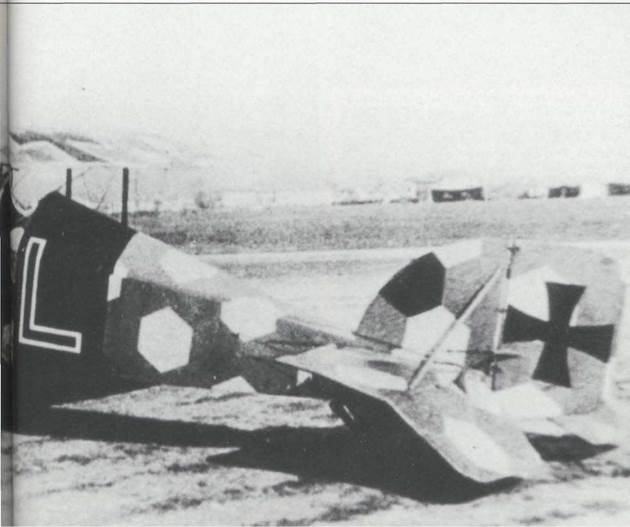

Bottom A slightly more powerful version of Halberstadt’s D I of late 1915, the D II entered service during the summer of 1916 as a replacement for the now obsolete Fokker Eindeckers. Powered by a 120hp Mercedes D II, its frail appearance belied what proved to be a robust structure. Top level speed of the D II was 90.1 mph at sea level, while its operational ceiling was around 13,000 feet. Carrying a single 7.92mm Spandau, probably just over 100 D Us were built by the parent company, plus Aviatik and Hannover. Halberstadt D II, 818/16, seen here, served on the Eastern Front. (Cowin Collection)

Below Halberstadt D IIs of Kampfgeschwader I operating from their base at Hudova in the Rumanian-Macedonia theatre of operations in 1916. (Cowin Collection)

Opposite Hauptmann Oswald Boelcke, pictured here sitting in his Fokker D III, 352/16, in which he led his newly formed Jasta 2, pending the arrival of the Albatros D I. Boelcke

|

|

commanded the unit between 1 September and his death, less than two months later, in an air-to-air collision on 28 October 1916. Born in Saxony on 9 May 1891, Oswald Boelcke, described as frail and bookish as a boy, joined a military academy in 1911, gaining a commission in August 1912. Already trained as a telegrapher, Boelcke transferred to the Imperial Army Air Service in mid-1914 to gain his wings days after the outbreak of war. Boelcke spent the rest of 1914 flying Albatros B IIs with Fl Abt 13. Early in 1915, Boelcke found himself tempoarily grounded with asthma, leading to his spending two weeks in the Air Service Headquarters, where he was to make some extremely useful senior level contacts. Boelcke, on his return to flying, joined Fl Abt 62 with Albatros C Is and LVG B IIs. After an uneventful spring, the unit moved to the front in the early summer. On 4 July 1915 Boelcke’s observer downed their first victim, a Morane-Saulnier Type L Two days later Boelcke switched to flying the newly arrived Fokker Eindecker single seater, with it interrupter-geared fixed, forward-firing gun. Between then and 21 May 1916, Boelcke scored a further 17 confirmed victories, most of which were obsolescent two seaters. Incidentally, operating alongside Boelcke during this period was Fl Abt 62’s other single seat section pilot, Max Immelmann. Between them the pair had well and truly opened the era of the Fokker Scourge. In November 1915, Boelcke was posted to the Air Service’s Operational Headquarters, at Charlesville, for a three month attachment. Here, Boelcke’s academic skills came into play as he wrote what was to become the standard German Fighter Pilot’s Rule Book for the rest of the war. Promoted Hauptmann, or captain, in May 1916, Boelcke was rapidly becoming too valuable to be allowed to continue combat flying and he was sent east to lecture tour on air fighting tactics. On 1 July 1916, the British opened their Somme Offensive, leading to the front line air service units coming under mounting pressure. Boelcke, currently in Bulgaria, was recalled to flying duties as commander of Jasta 2, for whose formation and personnel selection he was responsible. Among those Boelcke selected to fly with him was a young man named Manfred von Richthofen, along with, ironically, Erwin Bohme, the man who was, inadvertently, the cause of Boelcke’s death. Between 1 September 1916 and his death, Boelcke added a further 22 victories to bring his ultimate confirmed score to 40. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

Right Although favoured by Germany first great air ace, Oswald Boelcke, who flew Fokker D III 352/16 and scored six of his forty victories in this machine, the type was not generally liked by front line pilots, perhaps because of a lack-lustre performance, not helped by Fokker’s retention of wing warping, rather than ailerons. The Bavarian procurement authorities were even more critical, refusing to purchase the these Fokker biplanes at all until pressured from high places in Berlin. The Fokker D III made its operational debut in the spring of 1916 and, using the unreliable l60hp Oberursal U III, had a top level speed of 99mph at sea level. The D III was armed with two 7.92mm Spandaus. As an operational fighter, the career of the D III was brief, the type soon being relegated to advanced flying schools with many of the 230 built being delivered directly to train – 48 ing units. (Cowin Collection)

The period between the end of 1915 and the summer of 1917 can be seen as one of the low points in the fortunes of Fokker, the man and his company. This largely fallow time saw Fokker and his designers turn to biplane fighter designs, carrying the military designations D I to D V. As sometimes happens, the second of these, the rotary- powered Fokker D II was to emerge ahead of the in-line engined D I, of which only 25 were produced. Initially appearing at the front in the early spring of 1916, the D II was powered by a 100hp Oberursal U I. Armed with a single 7.92mm Spandau, the D II was woefully lacking in verve and agility, production being switched to the more powerful D III after only 61 examples of the D II had been built. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

The last of this series of comparative failures from Fokker, prior to the appearance of the much promoted Dr I triplane was the DV, the D IV never emerging as such. While the DV, of which 216 were built, showed far better pilot handling than its predecessors, it was deemed to be inferior to the Albatros D Us just coming into service and, like its immediate forebears, was re-directed to advanced training units. Delivery starting at the close of 1916, the DV was powered by a 100hp Oberursal U I and carried a single 7.92mm Spandau. Top level speed of the D V was 107mph, but climb rate was a fairly tardy 19 minutes to reach 9,800 feet. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

Jasta 25’s LFG Roland D II single seat fighters lined up on their Catnatlarzi base in Macedonia during 1917. First flown in October 1916, the twin 7.92mm Spandau armed D II was built in far greater quantities than either of the company’s D I or D III designs. Like the D I, the D II used a 160hp Mercedes D III that gave a top level speed of 105mph at sea level. Entering service in early 1917, a total of around 300 D IIs are believed to have been built, both by LFG and Pfalz. The machine was not unconditionally loved by its pilots, who found it particularly sensitive, especially in the yawing plane. Incidentally, this image, showing as it does no less than ten D IIs, goes some way to refute the often made claim that no unit seems to have been exclusively D ll-equipped. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

The Albatros D II, the fighter that turned the tide of the air war in Germany’s favour, at least for a while. Albatros had first flown their prototype D I fighter during August 1916 in answer to a pressing need to counter the current ascendency of the Nieuports and DH 2s. Flight testing of the D I showed it to be 49

fast, agile and with an excellent climb rate. The type was rushed into production so fast, that the first service deliveries were being made to Jasta 2 by early September 1916! Powered by a 160hp Mercedes D III, the less than 100 D Is built proved capable of reversing the Allies former fighter superiority. Acknowledging constructive criticism from the front line pilots, Albatros set about improving forward visibility by slightly lowering the upper mainplane to produce the D II in December 1916. With the exception of the lowered upper wing, the two machines were virtually identical. Again, D IIs were rushed to the front as soon as they were completed and tested, with LVG Roland and Ufag helping to spread the production load. Well over 300 of these 109mphtop level speed at sea level, twin 7.92mm Spandau-armed single seaters were to be built before production switched to the even better Albatros D III in early 1917.

A superb side view of a late production Albatros D II, 1076/17, still flying after 15 April 1918, as is immediately apparent from it having the angular Balkankreuse, or Greek Cross, in place of the earlier, curved Cross Patee. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

Opposite, top The Albatros D III, although having an entirely new wing, elsewhere embodied as much of the D II componentry as it could, revealing that Albatros’s Chief Engineer, Robert Thelen’s design philosophy lent towards doing things in an evolutionary, rather than a revolutionary manner. The D III can with hindsight be seen as the best of the Albatros single seaters, its successor, the D V incorporating too few real improvements over the D III at a time when the opposition was advancing apace. The D III, great aeroplane as it turned out, had one major inherent design flaw that led to wing flutter at high speed and consequent occasional structural failure and mid-air break up. The root of the problem by in Thelen’s decision to follow the Nieuport practice by adopting a sesquiplane, literally a one and a half wing layout. In doing this. Thelen fell into the same trap that the Nieuports had already experienced and had never really solved. In essence, the trouble lay with the combination of a torsionally weak, small lower wing being made to twist and oscillate through then little understood aerodynamic loads transmitted to it via the ‘V type interplane struts. This led to D III pilots being prohibited from diving the machine above a certain speed; quite a constraint for pilots who at some time or another were going to rely on the aircraft’s ability to break away quickly from combat with a superior opponent. Shown here is an initial production model Albatros D III, delivered to Jasta 29 in early 1917. Although very kind in terms of pilot handling, these early D Ills, besides being dive limited had another hazard in the form of the radiator that can just be seen positioned immediately ahead of the cockpit and filling the space between fuselage and upper wing centre section. If hit during combat, the radiator fluid could readily scald the pilot and frequently did. The solution was to move it to the underside of the upper starboard wing. In all, more than 1,300 D Ills were built, the first being delivered to the front in January 1917. While the sea level top speed of the D III was the same as that

for the D I and D II, its speed at height was improved through the use of a high compression Daimler D III. Armament comprised the by-now standard twin 7.92mm Spandaus. The D Ill’s heyday in the spring of 1917 began to fade by the summer when encountering the new Allied fighters in the shape of Sopwith Camels, Royal Aircraft Factory SE 5s and Spads. (Cowin Collection)

A later production Albatros D III, showing the new radiator position displaced to the starboard, underside of the upper wing centre section. (Cowin Collection)

Top right An extremely rare image, taken sometime after 15 April 1918, showing an Albatros D III fitted with additional small, load-spreading ancillary struts at the lower end of the normal ‘V interplane struts., clearly aimed at alleviating the high speed flutter problem. As these added struts have never appeared in any other picture of an Albatros D III seen by the author, he suspects that this fit was a locally devised modification. (Cowin Collection)

Lt Hans Adam of Bavarian Jasta 35, seen in the cockpit of his Albatros D III, 210I/I6.Adam, with 21 confirmed ‘kills’, met his own end in the skies over Mortvilde on 15 November 1917, while flying with Bavarian Jasta 6. (Cowin Collection)

OverleafThis image of Offstv Edmund Nathanael, standing with his Albatros D III of Jasta 5, helps point up the fact that noncommissioned ranks formed a significant part of the total flying personnel strength, although perhaps less so in fighter units than 51

elsewhere. Nathanael had scored 14 confirmed before being killed near Bourlon on 17 May 1917. (Cowin Collection)

This early production Albatros D III of Lt Dornheim, Jasta 29, having its radiator put under scrutiny. This image is also useful in showing the standard starboard side-only position of the Mercedes D Ill’s exhaust manifold. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

The sole prototype Zeppelin-Lindau V-l single seat fighter, completed during the summer of 1916, was not just Claudius Dornier’s first attempts at a fighter, but one of his first on any type of aeroplane. Of workmanlike, rather than elegant appearance, the finished product showed the influences of Nieuport’s

sesquiplane wing layout, in a British-style pusher engined airframe. Using a l60hp Mercedes D III, the V-l, as to be expected of Dornier, employed an all-alloy structure. Sadly, someone had miscalculated the machine’s dynamic, or in-flight balance. This was something the company’s test pilot, Bruno Schroter, clearly suspected to be the case following his high speed taxying tests and he wanted nothing more to do with the V-l. The man found to make the the aircraft’s maiden flight was Oblt Hallen von Hallerstein, a notable military flier, who had only recently completing the test flying of the giant Zeppelin- Staarken VGO III. Tragically, Schroter’s prediction concerning the aircraft’s tail-heaviness proved correct and on 13 November 1916, following lift-off, the V-I’s nose continued to rise until the fighter stalled and fell to earth, von Hallerstein being killed in the crash. (Cowin Collection)

The story of the Albatros D IV is a tale of the one that got away. Following upon the operational success of their D II and D III fighters, Albatros came up with the extremely logical idea of using the robust wing of the D II, married to a new elliptical sectioned fuselage, later to be adopted for their D V. This hybrid machine was the Albatros D IV of which only one was built. Up to now, Albatros’s thinking had been flawless, particularly as the reversion to the D II’s wing promised to prevent the occasional catastrophic high speed wing shedding being experienced with their ‘V strutted D III sesquiplanes, as narrated above. Where Albatros’s thinking went awry was in choosing to fit the prototype with an experimental geared variant of the 160hp Mercedes D III. This engine, which appears never to have worked satisfactorily, managed to delay D IV flight testing to the point where officialdom simply lost interest. With another engine, the D IV might have helped bridge the gap between the Albatros D III and the Fokker DVII, something the Albatros D V never quite did. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

Bruno Loerzer, an Oberleutnant at the time this picture was taken, when commanding Jasta 26 of JG 2. Born on 22 January 1891, Loerzer is seen standing besides his Albatros D V. Awarded the Order Pour Le Merite, Germany’s highest military honour on 12 February 1918,

Loerzer went on to become a Hauptmann, the equivalent to a US Captain or RAF Squadron Leader, when promoted to lead JG 3. Loerzer ended his war with an accredited 44 ‘kills’, placing him 8th in the ranking of German leading air aces. (Cowin Collection)

|

Earty in 1917, while the Albatros D IV saga was still unravelling, as dealt with above, the firm produced its first D. V. As it transpired, while adequate and built in massive numbers, this design served to prove the law of diminishing returns. In essence, the Albatros DV employed exactly the same wings as the D III, along with the tailplane and elevator, all of which were interchangeable between the two fighters. Initially, even the fin and rudder were identical, but later fin area was increased, leading the to the D Vs characteristically rounded rudder trailing edge. Married to these components. Albatros took the new, semi-monocoque fuselage developed for their D IV and, for good measure, further lowered the upper wing in relation to the fuselage in order to yet further improve the pilot’s forward visibility. The engine in early D Vs remained the 160hp Mercedes D III, replaced in the structurally strengthened D Va with the 185hp D IlIa. Both the German Air Ministry and Albatros appeared happy with the resulting machine, despite the fact that its top level speed of 116mph at 3,280 feet, or for that matter the fighter’s agility, were little improved compared with the D III. Further, the high speed lower wing flutter of the D III was still present, restricting high speed flight and, therefore, limiting the combat pilot’s primary option of diving away from trouble. The armament comprised the standard twin 7.92mm Spandaus. Initial deliveries of D Vs were made to the front in July 1917 and rapidly built up from that point on, with Albatros output being joined by that of their Austrian subsidiary OAW During the autumn of 1917, DV production was switched to the strengthened and more powerful D Va. No precise production totals have survived for the DV and Va, but the knowledge that at their respective peaks of November 1917 and May 1918, no less than 526 D Vs along with 986 examples of the DVa were in service, would, allowing for attrition and spares, indicate a minimum overall build exceeding 2,200 machines. There is reason to believe that all 80 Jastas operating in the spring of 1918 had, at least, some D V or Va on their strength. The early DV depicted carries the Bavarian Lion motif of Hpt Eduard flitter von Schleich, leader ofJasta 21, who survived the war with a Pour Le Merite (‘Blue Max’) and a confirmed 35 ‘kills’. The pilot’s headrest, seen in this image, was not particularly favoured by operational pilots and was soon removed from most machines. (Cowin Collection)

Destined to head the Luftwaffe in World War II, Hermann Goring is pictured here, second from left, with his newly delivered Albatros D V. At this time Goring was serving with Jasta 27 and had just scored his fifth ‘kill’. He was to finish the war as a Hauptmannn, commanding JG I, the post he took over following the death of Baron Manfred von Richthofen. Goring was a holder of the Pour Le Merite and had 22 confirmed victories. (Cowin Collection)

An interesting frontal aspect on the Albatros D Va, believed to have belonged to a Bavarian Jasta and which from the presence of wheel chocks and the mechanic holding the tail down is seen undergoing engine running tests. (Cowin Collection)

Above Lt Schlomer poses nonchalantly beside his Albatros DVa in the late summer of 1917. Schlomer had became leader of Jasta 5, following the death of Oblt Berr at Noyelles on 8 April 1917. Schlomer, himself was to be killed just over a year and a month later, on 31 May 1918. (Cowin Collection)

Below Oberleutnant Freidrich Ritter von Roth, seen here standing beside his Albatros D Va, was born of aristocratic parents on 29 September 1893. Having volunteered at the outbreak of war, ‘Fritz’, as he was popularly known, joined a Bavarian artillery regiment and was almost immediately promoted to sergeant. Wounded in action soon after, Roth was

The other side of the coin. To counterbalance the romantic view of air combat is this image of the debris of what had been Oblt Hans Berr’s Albatros D V, in which he was killed south of Noyelles on 6 April 1917. Berr had been the first commanding Officer of Jasta 5 and died with a confirmed score of 10 victories. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

commissioned on 29 May 1915 while still recuperating. Transferring to the flying service and pilot training towards the close of 1915, Roth was severely injured in a flying accident that delayed his gaining his wings until early 1917. Roth’s first operational experience was gained with Fl Abt 296, a two seater unit, then based at Annelles, as part of the 1st Army, which he joined on 1 April 1917. Roth moved to fighters in the autumn of 1917 and after a busy closing quarter of 1917 and early 1918, during which he had served with Jastas 34 and 23, he was given command of Jasta l6 on 24 April 1918. Meanwhile, Roth’s first confirmed ‘kill’ was made on 25 January 1918 and involved the dangerous business of downing a heavily defended balloon. As balloons were considered a vital tactical reconnaissance tool by both sides and were always heavily defended, it is a measure of the man that Roth appears to have subsequently specialized in attacking balloons, being credited with no less than 20 of them out of his total 28 confirmed vicories. Dispirited by the impact of the Armistice and the dissolution of his beloved Air Service, Freidrich Ritter von Roth took his own life on New Year’ Eve, 31 December 1918. (Cowin Collection)

Top right With only a handful built, the AEG D I was one of the rarer types to find its way into front-line service with the single seater units during the latter half of 1917. Armed with twin 7.92 Spandaus and powered by a 160hp Mercedes, this diminutive fighter had a useful top level speed of 124mph, but this could well have been counter-balanced by poor climb, tricky handling and longish take-off requirement, if the machine’s wing loading was as high as the photograph would suggest. The AEG D 1,4400/17, shown here belonged to Lt Walter Hohndorf, leader of Jasta 14. It was in this fighter that Hohndorf crashed to his death on 5 September 1917, after a combat in which he had scored his 12th ‘kill’. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

Below First flown around June 1917, the clean-looking Pfalz D III, like its near contemporary, the Albatros DV, was to prove inferior to the Camel, SE 5 and Spad that were to be encountered in ever growing numbers from the summer of 1917 onwards. Initially deployed operationally in late August 1917, the 160hp Mercedes D Ill-powered machine lacked the agility and climb capability of the Albatros DV, but was faster than the D V, having a top level speed of 112mph at sea level, falling to 103mph at 9.840 feet. Further, the Pfalz D III was extremely robust and suffered none of the wing flutter problems of the Albatros series. It was therefore useful for fast attack missions such as those against well defended balloons. The one area that pilots were particularly critical of in the D III was that of climb, the D III taking 7 minutes to reach 5,000 feet, compared with the SE 5A’s 5 minutes 35 seconds to reach the same height. Notwithstanding, the twin 7.92mm Spandau armed D Ill’s career paralleled that of the Albatros DV in as much as it was to be produced in an up-rated D IlIa form towards the close of

1917. Based on the operational numbers on record for April

1918,

the total Pfalz D III and IlIa build must have been around 1,000 machines. (Cowin Collection)

This initial production batch Pfalz D III of Lt Lenz, Jasta 22 was delivered in August 1917, when the unit was based at Vivaise. (Cowin Collection)

Pfalz D Ilia, serial 6014/17, photographed sometime after 15 April 1918, as indicated by the machine’s Balkankreuse markings. Although the Pfalz fighter equipped a large number of Jastas, it seems it never equipped any one exclusively. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

|

Bottom Each war has its glories and its myths and surely one of the greatest myths of the World War I airwar must be that centred around Anthony Fokker’s triplane fighter, the Dr I. Feared by its pilots as being structurally flawed, the Fokker triplane was only built in relatively small numbers, after which it was rapidly replaced by the much superior Fokker D VII. Just how was it then that to this day, the Fokker Dr I is thought of as one of the Allies’ greatest aerial adversaries? In part, the story involves the ‘Red Baron’, the publicity machine that surrounded him, as discussed in the frontispiece to this book and Anthony Fokker, who did his utmost to cultivate von Richthofen’s favour. The other major part of the story lies with the panic that befell the German Air Ministry in the wake of the Sopwith Triplane’s advent in February 1917, a panic. it should be said, that was greater than that which had followed the debut of the Nieuport fighters a year previously. With a climb rate better than that of any current German fighter, coupled to superb agility, the Triplane literally cut a swath through the enemy machines over the Somme. Top priority, urgent requests for proposals went out by telegram from Berlin to industry, Germany must have a counter, it must, therefore, have its own triplane. In fact, no less than twenty different types of German triplane fighter prototypes were to appear over the next twelve months, of which more later. What happened quite early on shows not only how Fokker stole the lead on his competitors, but also casts light on the Richthofen/Fokker relationship. Richthofen first encountered a Sopwith Triplane on 20 April 1917 and was impressed. He soon passed his impressions of the machine and its capabilities to Fokker during one of his frequent visits to the front-line airfields. Armed with this firsthand briefing, Fokker, whose fighters had lost much of their credibility, put his design and engineering team onto the

triplane project right away, thus gaining two months lead on the nearest of his competitors. By July 1917, Fokker had flown and tested his V3 prototype with fully cantilevered wings, that is with no interplane struts, that were added to V4, in the shape of simply T struts, to cure wing vibration. V4 became the first of three pre-production examples, carrying the military designation F I. Granted service clearance in mid August 1917,

triplane project right away, thus gaining two months lead on the nearest of his competitors. By July 1917, Fokker had flown and tested his V3 prototype with fully cantilevered wings, that is with no interplane struts, that were added to V4, in the shape of simply T struts, to cure wing vibration. V4 became the first of three pre-production examples, carrying the military designation F I. Granted service clearance in mid August 1917,

Fokker, himself, accompanied the second and third of these machines to Courtrai, where he personally gave Manfred von Richthofen and Werner Voss their type checks on F Is, serial 102/17 and 103/17, respectively. Deliveries ofthe 318 production examples, by this time redesignated Dr I, started in mid – October 1917. Unfortunately, for at least two early recipients of the Dr I, Lt Heinz Gontermann of Jasta 15, an Orden Pour Le Merite holder with 39 ‘kills’ and Lt Pastor of JG I, their machines broke up in mid-air on 30 and 31 October 1917, the pilot being killed in each case. The problem was a flawed wing requiring the withdrawal of the Dr I pending rectification. Strengthened and returned to service by December 1917, the Dr I was always subsequently viewed with some suspicion by its pilots, the type being relegated to second-line duties as soon as possible as Fokker D VIIs were delivered. Shown below opposite is von Richthofen sitting in his F I, 102/17 and chatting with fellow pilots of his fighter wing, JG I. (Cowin Collection)

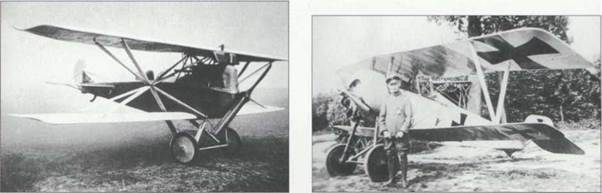

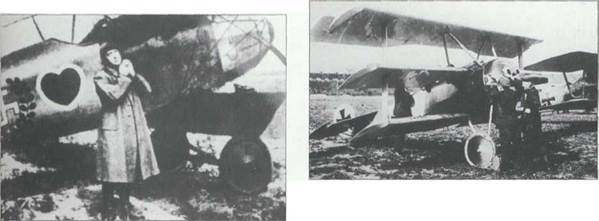

Lt Werner Voss stands in front of his Fokker F I (above right), 103/17, which as leader of Jasta 10 he had received on 29 August 1917 and the machine in which he was to die less than a month later, on 23 September 1917. Werner Voss, born 13 April 1897, was not yet eighteen when he enlisted in a Hussars Regiment just prior to the outbreak of World War I. In August 1915, he transferred into flying, initially as an observer, where he survived the Battle of the Somme, launched on 1 July 1916 and a period when the Allies held superiority in the air. Voss left the front in August 1916 to be trained as a pilot, joining Jasta 2 on 21 November 1916, flying Albatros D Ills. Six days later Voss scored his first ‘kill’. By the end of February 1917,VOSSS score

was 22 and on 8 April 1917 he was awarded the Pour Le Merite. Voss went on to join Jasta 5, where he added a further 12 "kills’ flying against the French, before taking command of Jasta 10 on 31 July 1917. Here, facing the British, Voss added another 14 victories, taking his total tally to 48 before he elected to fly just one more sortie prior to going on leave with his two brothers. Voss had the misfortune to encounter the handpicked SE 5a pilots of No 56 Squadron, RAF and succumbed to their guns. Voss was the 4th ranking German air ace of the war. He is seen below left standing beside his Albatros D III of Jasta 2, decorated with his personal emblem. (Cowin Collection)

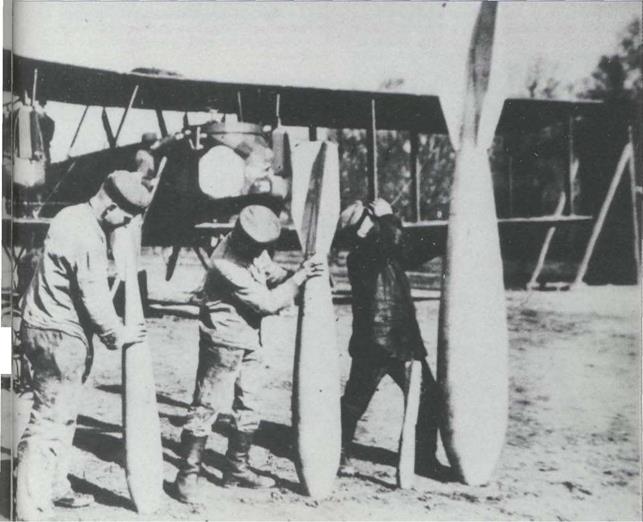

With a mechanic ready to swing the propeller and two more in attendance, this Fokker Dr I pilot prepares for take-off. Alongside the Dr I is a Pfalz D III of the same Jasta helping illustrate the mixture of types that remained characteristic of German front-line Jastas all the way through to the Armistice. In contrast, the British and French had long since realised the logistical, maintenance and operational benefits of standardising aircraft and engines at squadron level. (Cowin Collection)

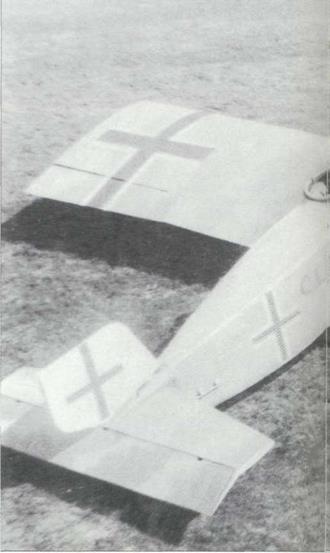

Overleaf, top One of the runners-up in the great German triplane fighter requirement saga in the summer of 1917 was this neat-looking Pfalz Dr I. First flown in the autumn of 1917, the Pfalz Dr I used a 160hp Siemens-Halske Sh III rotary, giving the 57

machine an almost incredible top level speed of 125mph at sea level. The twin 7.92mm Spandau armed machine was given two operational evaluations, one in October 1917, followed by a second, conducted by Manfred von Richthofen, in December 1917. Richthofen considered the Pfalz to be generally inferior to the Fokker Dr I. Recalling that it was the Bavarians, long time critics of Fokker products and in whose domain Pfalz was based, it would be interesting to know just when they went ahead and ordered a reported ten Pfalz Dr Is to be built. (Cowin Collection)

Below No less than eleven manufacturers produced triplane, single seat fighters in the summer of 1917, including Albatros, whose Dr I simply married a new triplane wing to an otherwise standard DV airframe. (Cowin Collection)

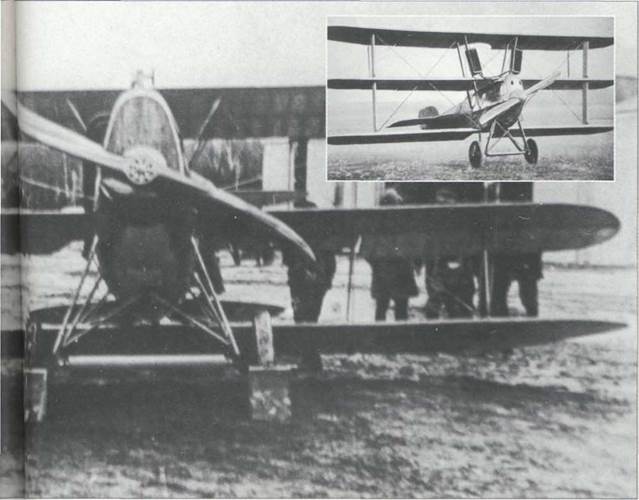

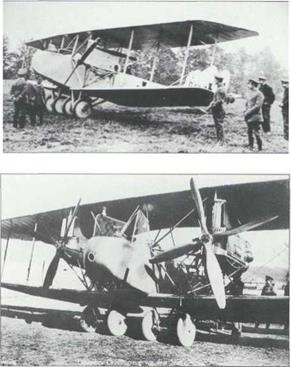

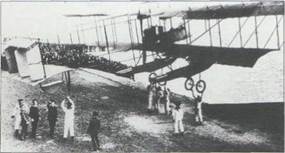

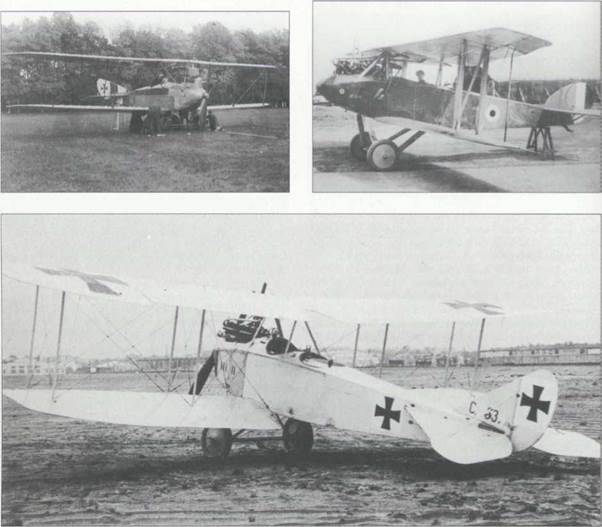

Three other triplane fighter essays of 1917 were the rotary- powered Euler Dr I, (opposite, top) the 1I85hp Austro-Daimler powered Hansa-Brandenburg L 16 (inset, right) and the Korting 58 engined DFW Dr I (mainpicture, right). (Cowin Collection)

Quite what Anthony Fokker and his designers were setting out to achieve with this conventionally-tailed, tandem-winged, quin – trupriplane monstrosity is anyone’s guess. Completed in the autumn of 1917, months after his Dr I, the sole Fokker V8 is

reported to have only made two brief hops, each time with Fokker at the controls before scrapping. (Cowin Collection)

Below Design of the Austrian Aviatik, or Berg D I commenced very early in 1917, slightly ahead of Austria’s other indigenous fighter, the Phonix D I. During the early stage of its flying career, the Berg D I suffered catastrophic structural wing failure, but once generally ‘beefed-up’, the machine proved to be both fast, agile and have a good climb, cited as reaching 13,000 feet in 11 minutes 15 seconds. Initially powered by a 185hp Austro-Daimler, these Bergs had top level speed of 113mph at sea level. The speed of later 200hp or 225hp powered aircraft rose to 115mph. Similarly, initial production Bergs carried a single 8mm Schwarzlose, while a second was added to later fighters. Delivered primarily to serve on the Italian Front from the late spring of 1917 onwards, the Berg D I was built in some quantities, involving 4 sub-contractors probably producing more than 300 machines. The fighter shown here was the mount ofAustrian air ace, Oblt Frank Linke-Crawford, leader of Flik 60. (Cowin Collection)

Right Hptm Godwin Brumowski survived the war as Austro – Hungary’s leading air ace with a score of 40, according to Austrian sources, or 35 if using Hungarian figures. Incidentally this discrepancy is commonplace, with the Hungarian claims always being lower. Born on 26 July 1889, Brumowski was already a serving field artillery officer at the outbreak of war. He transferred to the army flying service in late 1915, training as an observer. It seems that Brumowski, with the help of squadron colleagues, then taught himself to pilot an aircraft, leading to him being given command of Flik 12 in early 1916. Flik 12 was a mixed unit with both two and single seaters and Brumowski’s frustration mounted at the operational doctrine of using the single seaters exclusively as two seater escorts. Seconded to study German air operations on the Western Front during the summer of 1916, Brumowski returned, persuading his seniors to give him leadership of an all fighter unit, Flik 41. Brumowski and his squadron operated on the Italian Front for the rest of the war. Initially equipped with Hansa-Brandenburg D Is, the unit converted to Albatros D Ills in mid-1917. (Cowin Collection)

Derived from the Hansa-Brandenburg D I, the Phonix D I adopted a more conventional interplane strut arrangement and a prominent fin. First flown in mid-1917, the Phonix D I entered service in February 1918, with 150 going to the Austro – Hungarian Army air arm and 40 to the Austro-Hungarian Navy. Not particularly agile, the D I, with its 200hp Hiero, had a top level speed of 112mph at sea level and was said to have a good rate of climb. Armed with twin 8mm Schwarzlose, the proneness of these guns to jamming, along with their inaccessibility in the D I was a point of major criticism. The machine seen here was the 45th of the second 50 production batch. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

The single seat Pfalz D VII fighter of late 1917 never progressed beyond the prototype stage. Using a 160hp Siemens-Halkske Sh III rotary, this Pfalz machine was one of 23 entrants put forward for the first of three 1918 competitive fighter trials, all at Alderhof, near Berlin, this one being held in late January and early February. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

Oblt Ernst Udet, seen here standing in front of his Fokker D VII ‘Lo’ was born on 26 April 1896 and was to become the last commander of Jasta 4, having previously served with Jastas 15, 37 and 11. At the time of the Armistice, Udet was a Pour Le Merite holder, with 62 confirmed victories, which makes him Germany’s second highest scoring ace of the war after Baron Manfred von Richthofen. Udet remained prominent in post-war German aviation circles, particularly as an aerobatic pilot and lent his name to an aircraft manufacturer during the 1920s. Along with a number of other former prominent military fliers, Udet rejoined the Luftwaffe in 1935 with the rank of 62 Generaloberst, the equivalent of a four-star general or Air

Chief Marshal. Subsequently blamed for shortfalls in aircraft production, Udet took his own life on 17 November 1941. (Cowin Collection)

Opposite, top Although slower than many of its competitors, the Fokker V II prototype’s easy handling and reluctance to spin endeared the aircraft to the trials pilots, unanimously adjudging it the overall winner of the first of the 1918 Alderhof fighter

trials. As there was an urgent need for an initial 400 of these single seat fighters, a figure beyond Fokker’s ability to meet on time, contracts were placed simultaneously with Fokker and Albatros, with AEG being drawn in later. Given the military designation Fokker D VII, the machine was powered initially by a 160hp Mercedes D III, this being soon replaced by the 185hp BMW llla. This latter engine pushed the top level speed up by 7mph, to 124mph at sea level and had an even more dramatic effect on the fighter’s rate of climb, with the time to reach 3,280 feet dropping to 2.5 minutes from 3.8 minutes for the earlier Mercedes powered examples. Rapid as it was, with first operational deliveries being made in April 1917 to JG I, the Fokker DVII’s passage into service appears to have been essentially trouble-free. Even more significantly, no subsequent fatal flaws, such as those experienced with Fokker’s Dr I, were to emerge. At last Anthony Fokker and his chief designer, Reinhold Platz, had produced a real winner that would not only keep the factory full, but would soon come to earn the respect of the all the Allied pilots who encountered it. Armed with the standard twin 7.92mm Spandaus, over 800 examples of the D VII had been delivered to 48 operational Jastas by the start of September 1918. Showing off its well proportioned lines, Fokker D VII, 507/18, seen here, reportedly served with the famed Jasta Boelcke. (Cowin Collection)

Right The youthful Lt Ulrich Nechel standing near his Fokker D VII. Nechel, born on 23 January 1898, was still aged only twenty at the time of the Armistice. Despite this, Nechel’s confirmed score of 30 ‘kills’, coupled to his leadership qualities had seen him selected to command Jasta 6 during the last months of the war. Prior to this, Nechel had served with Jastas 12 and 19. He was awarded the Pour Le Merite on 8 November 1918. (Cowin Collection)

The compact Pfalz D VIII was completed in time for the second of the 1918 fighter competitions and showed sufficient promise to warrant a production contract. Powered by a 160hp Siemens-Halske Sh III rotary, the twin 7.92mm Spandau-armed D VIII had a top level speed of 120mph at sea level. Production was just getting underway at the time of the Armistice, with 40 or so completed. The example seen here was one of 20 that were undergoing operational evaluation at the front. (Cowin Collection)

Lt Emil Thuy, as commander of Jasta 28 with his Fokker D VII, 262/18.Thuy had been given Jasta 28 after learning his craft with Jasta 21.A Pour Le Merite holder, Thuy survived the war with a confirmed 32 victories. (Cowin Collection)

Top One of Albatros’s less notable designs, their D XII. The first of the two D XII built used a 180hp Mercedes Dllla and first flew in March 1918, the second, powered by a 185hp BMW IlIa, following it into the air a month later. Top level speed of the first D XII, seen here, was cited at 115mph at sea level. The second aircraft took part in the third of the 1918 fighter design competitions, held in October. (Cowin Collection)

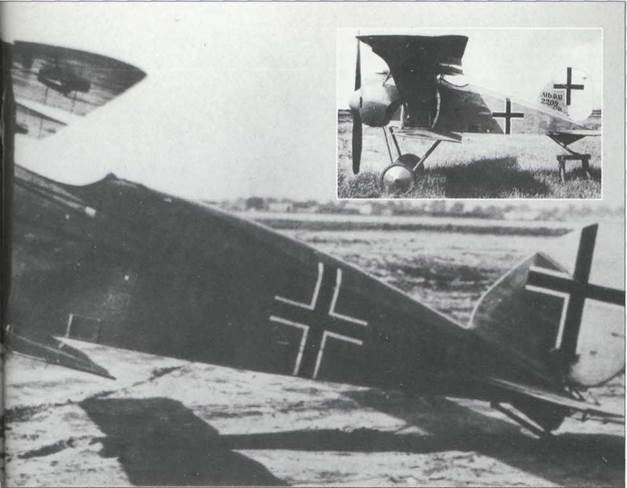

Inset The second of the two Albatros D XI fighters, 2209/18, entered into the second 1918 fighter competition, held in May and June. The pair of small and stubby D Xls were among the 37 competitors entered, the overall winner being Fokker’s V 28, precursor to the Fokker D VIII rotary powered, parasol winged monoplane fighter. (Cowin Collection)

Left Thanks to the relatively protracted development of the LFG Roland D Vlb, only a small number of this 200hp Benz Bz IlIa powered single seater reached the Western Front prior to the Armistice. A handful also found their way to the Navy, where they were used to defend seaplane bases. Armed with twin 7.92mm Spandaus. the DVib had a top level speed of 124mph at sea level, falling sharply to 113mph at 6,560 feet. (Cowin Collection) 65

The Pfalz D XII was another newcomer to the front in the last months of the war, having been selected for production as a result of its performance in the second of the 1918 Adlershof fighter competitions. AtAdlershof. no less than three Pfalz D XII precursors had been entered, each having a different engine, with the I80hp Mercedes Dllla being chosen to power the production aircraft.

Readily distinguishable from the Fokker DVII by it second bay, or set of interplane struts, the twin 7.92mm Spandau armed Pfalz D XII started to enter operational service in September 1918, examples of it going to ten front-line Jastas. Initially seen as second best to the Fokker DVII, the D XII, with its I20mph top level speed at sea level proved slightly faster than the Fokker, which it could also outdive. However, perhaps the most endearing quality possessed by the Pfalz fighter was its ability to withstand a great deal of combat damage and still get its pilot home. With production only just having started up, only 90 to 100 D XI Is are thought to have been completed at the time of the Armistice. (Cowin Collection)

While some of Anthony Fokker’s business practices may have been questionable, the one thing he could never have been criticised about was his attitude towards aircraft development. This manifested itself in a prolific string of prototypes that left most other manufacturers gasping. Although largely overlooked today, these prototypes occasionally bore impressive fruit, as in the case of Fokker’s last production fighter of the war, his monoplane D VIII. The story of the D VIM begins early in 1918 with one of those Fokker and Reinhold Platz ‘What if?’exercis – 68 es involving removing the lower wing from the one of the two

Fokker D VII biplane prototypes. This proved a less than ideal solution, so Platz tried it again with the V 26, a lighter, rotary – powered one-off that used the Junkers-devised thick sectioned wing. This one worked, in fact so successfully, that Fokker set all hands to producing the fully militarised E V to be ready for the second of the 1918 Adlershof fighter trials. Here, in the rotary – powered class fly-offs the lightweight Fokker E V swept the competition aside, very much as its forebear, the D VII had done a few months previously. However, from this date on, the story of the EV, later D VIII, takes on the more sobering tones of the the Fokker Dr I saga, for hardly had the first E Vs started to

flow to the front in July 1918, than the type had to be withdrawn in August, following a series of fatalities. The problem, it transpired, was a readily remedied one concerning wing glueing practices. Nonetheless, the E V was out of service from the end of July 1918 until cleared in October, robbing the front-line Jastas of a potentially admirable fighter when most needed. Powered by a 110hp Oberursal U II, the newly returned DVIIIs, as they were now known, were only two-thirds the weight of the Fokker D VII, which, coupled to the DVIII’s high lift efficent wing, gave the fighter both agility and an admirable rate of climb. Armed with twin 7.92mm Spandaus. the Fokker D VIII’s

top level speed was 115mph at sea level, rising to 127mph at optimum altitude. The time cited to climb to 3,280 feet was 2 minutes. This is one of the initial batch of EVs, 149/18, delivered to JG I in July 1918. Around 60 of these machines are reported to have been produced prior to the type’s temporary withdrawal, perhaps another 40 may have been completed but not yet delivered at the time of the Armistice. Certainly a number of D VIIIs were among the 143 aircraft that Fokker ensured were removed, along with most of his plant’s machine tools, when he fled back to his native Holland. (Cowin Collection) 69

|

The Phonix D III emerged in mid-1918 in response to fighter pilots’ criticism of the Phonix D I and ll’s excessive degree of stability. What they wanted, above all, was a machine that could be thrown about with ease, not effort. What Phonix did on their D III was to take off the dihedral, or tilting up of the wings from the fore-and-aft centre, and to add a second pair of ailerons to the lower wing. These modifications, along with the use of a 230hp Heiro engine improved both agility and top level speed to 121mph at sea level. Seen here is the prototype D III, production deliveries of which were only beginning to reach the Austro-Hungarian line units at the time of the Armistice. The type, however, did go on to serve with the Swedish forces, who bought 17 in 1919 and built a further 10 locally in 1924. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

Bottom Little in the way of hard fact appears to have survived concerning the pair of parasol-winged LFG Roland D XVIs of mid-1918, other than that they were powered by the 160hp Siemens-Halske Sh III or 170hp Goebels rotaries. Both were entered for the third of the 1918 fighter trials, held in October. This is the first example, the second machine having a taller fin and rudder. (Cowin Collection)

Top, right Perhaps the best fighter Germany never had in 1918 was the 1917 Rumpler D I. With a top level speed of 112mph at 16,400 feet, along with an ability to reach 26,300 feet, the Rumpler D I had an unmatched performance at altitude and could more than hold its own in terms of speed and agility lower down. Rumpler entered two D Is in the second 1918 fighter trial, both reportedly using the 180hp Mercedes Dllla. Perhaps fortunately for the Allies, the D I appears to have been difficult to build as there is no indication of deliveries being made to the front, even though an order for 50 had been placed immediatedly following the May-June trials. A third D I, equipped with a 185 BMW IlIa took part in the October 1918 fighter trials. The two men seen here with Rumpler D I, 1589/18, at the second Aldershof trials are Ernst Udet on the left and Herr Rumpler himself. (Cowin Collection)

Below The Siemens Schuckert D III was another impressive machine that found its way into limited service during 1918. Initially delivered to JG 2 in April, the 53 D Ills built were also used to equip five home defence units, known as Kests. While slow near the ground, with a top level speed of only 113mph at sea level, the D Ill’s speciality lay in its phenomenal climb, capable of taking the machine to its 26,240 feet ceiling at a rate far outstripping that of both the Fokker D VII and D VIII. This meant that the D III was ideal for rapid reaction responses to high flying threats, which in World War II would be called local or point air defence missions. At the heart of the fighter was its 160hp Siemens Halske Sh III, a throttleable, high compression rotary, whose twin banks of cylinders counter-rotated to minimise the gyroscopic-effect handling problems of the conventional rotaries. The D III gave way in production to the improved D IV Shown here is non-commissioned officer pilot Leim and his mechanic of Kest 4b posing proudly before their Siemens Schuckert D III. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

Above A brand new Siemens Schuckert D IV seen prior to leaving the factory. While using the same 160hp Siemens Halske Sh III as its immediate forebear, the D IV had its wing area cropped to increase top level speed to 119mph at sea level. However, the reduction in wing area brought an increase in wing loading, making the D IV trickier to handle than the D III, particularly in the lower speed regime, where any tendency to spin would be reinforced. The D IV still retained an ability to outclimb any of its contemporaries, making it an admirable ‘top cover’ aggressor at the front, or rapid-response, high altitude defender of the homeland. To give a glimpse of the D. IVs ability to climb, its time of 1.9 minutes to reach 3,280 feet was superior to that of both the SE 5a and the newly deployed Sopwith Snipe, an advantage the D IV retained on up to a 26,240 feet ceiling. Initially delivered to the service in late August 1918, only 50 or so D Vis were thought to have been delivered by the Armistice. (Cowin Collection)

|

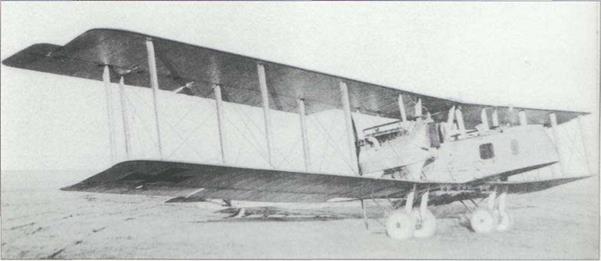

Right Developed as a synthesis of both the Junkers J.7 single seater and J.8 two seater, the short-fuselaged prototype J.9 rolled out of the Junkers plant at the end of April 1918. Powered by a 185hp BMW IlIa, this unarmed, light alloy machine achieved a remarkable top level speed of 149mph at sea level. Surprisingly, the top level speed of the definitive, long – fuselaged, armed production J.9, was only 4mph slower, at 145mph. In a classic case of bi-focal thinking the military gave the J.9 the designation Junkers D I, where D stood for Doppledecker, or biplane, as they had with Fokker’s D VIII. Depicted here is a recently ex-factory D I awaiting delivery on 8 July 1918. As already mentioned with reference to the Junkers J.4JJ I, production engineering was the company’s real weakness 72 and only a handful of the 41 completed twin 7.92mm Spandau-

|

armed single seaters were to reach the Western Front prior to the Armistice. Junkers D Is, however, did manage to find their way into Poland and the Baltic States, where they continued to fly and fight, along with their two seat Junkers Cl I bretheren with the Geschwader Sachenberg. (Cowin Collection)

Above Despite carrying the Zeppelin-Lindau name, the division headed by Claudius Dornier the D. I, first flown on 4 June 1918, was designed by Adolph Rohrbach, head of the Zeppelin – Staaken division Like its few Zeppelin-Lindau forebears, this latest single seat, biplane fighter used light alloy as its primary structural material. Externally, the 185hp BMW IlIa powered D. I was an exceptionally clean design, with fully cantilevered wings and tail unit, bereft of any external and, hence, drag – producing bracing struts or wires. Rushed through the design and assembly phases in order to compete in the second 1918 Adlershof fighter competitions, the disassembled D. I was dispatched by train immediately after its maiden flight. Reportedly, while still in transit, someone re-checking at the factory discovered that the upper wing attachment fittings were too weak and alerted Adlershof not to fly the aircraft until strengthened fittings could be rushed to them. Sadly, whether the information was not received, or simply ignored, the D. I was flown twice after re-assembly, Hermann Goring being the first service pilot to fly it, followed by Hptm Wilhelm Reinhardt, who lost his life after the upper wing detached in mid-air. At least two other D. Is were built, as two found their way to the US soon after the war, to be tested by the US Army and Navy, respectively. Earlier German testing had been critical of the aircraft’s lack of speed, said to be 124mph at sea level, and general heaviness of the controls. (Cowin Collection)

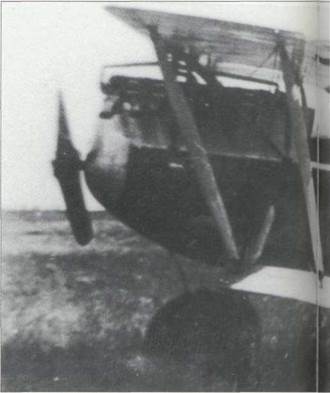

Right The last of a long line of LFG Roland fighters, their D XVII single seater was fitted with a 185hp BMW Ilia. Little reliable data survives on this machine, which is reported to have taken part in the second of the 1918 fighter trials. Note the position of the radiator, mounted to project forward of the wing centre section leading edge. This allowed the engine to be more smoothly cowled, but whether the radiator’s position encroached upon the all-important fighter need for excellent forward pilot visibility is difficult to judge from this image. (Cowin Collection)

Below Another contender and Fokker D VIII look-alike that took part in the third 1918 Adlershof fighter trial, held in October, was the Kondor E 3a seen here. The E 3A employed a 180hp Goebel rotary. A second specimen, the 160hp Oberursal U III powered Kondor E 3, also participated in this competition. The external wing ribbing, along with the aft wing centre section cut-out help to highlight that this design employed the still novel thick sectioned, high lift wing. Top level speeds for the E 3 and E 3a were reported to be 120mph and 124mph, respectively. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

Below right A revealing side view of the Phonix D IV single seater of which only two prototypes had been completed at the time of the Armistice. While superficially similar to the earlier Phonix D I to D III series, the D IV was virtually a totally new design. Gone were the slab-sided fuselages of the earlier machines, to be replaced by a generally smoother, oval – sectioned body, terminating in a fin and rudder of significantly increased areas. Little information survived the war concerning the D IV’s performance. From this image, it would seem that the Austro-Hungarians did not follow their German allies in switching to using the straight-sided Balkankreuse national marking from mid-April 1918. (Cowin Collection)

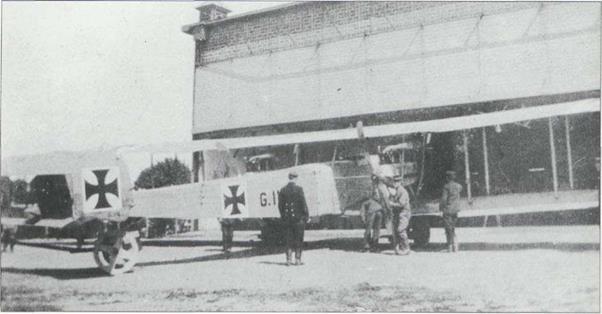

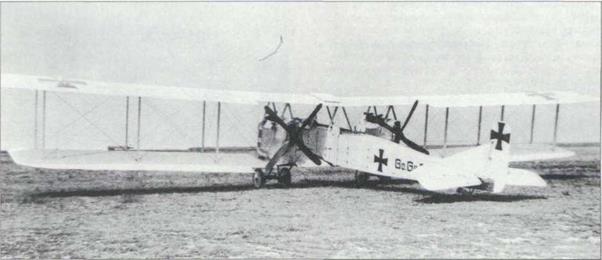

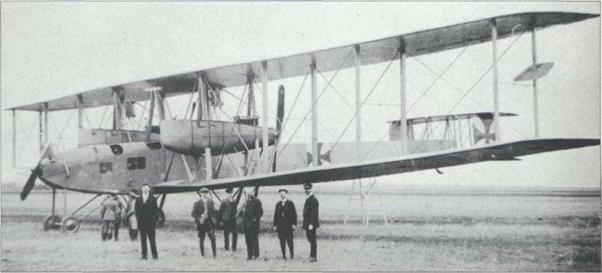

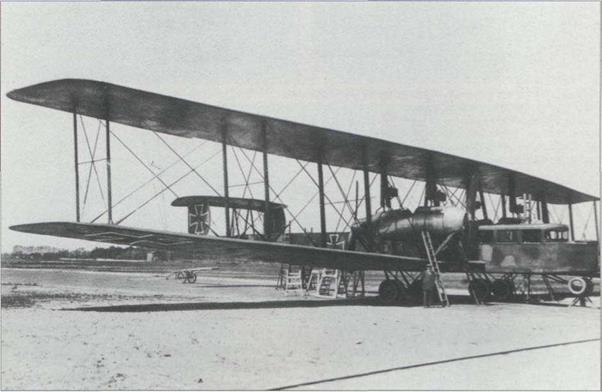

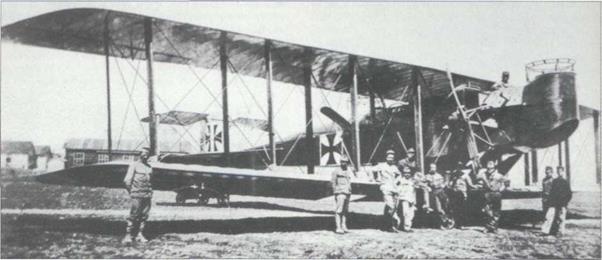

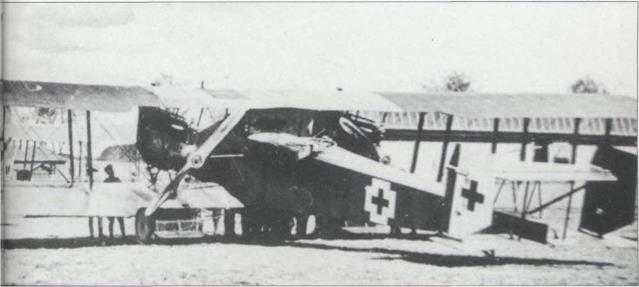

Although always overshadowed in the public eye by the Gotha name, the Fnedrichshafen G III equipped three of the eight German bomber wings at the time of the Armistice. Larger and heavier than the contemporary Gotha G IV, the G III carried a far heavier bomb load and seemed far less susceptible to the landing gear failures that constantly beset the Gothas. With a 3- man crew, the G III was powered by two 260hp Mercedes D IVs and could carry up to 3,300 Ib of bombs. Armed with two or three 7.92mm Parabellums, the G III had a top level speed of 87mph at 3,280 feet, along with a duration of 5 hours, implying a tactical radius of action, with full bomb load, of around 140 to 145 miles. Deployed initially in mid-1917, the G III and G IlIa went on to equip KG 1, KG 2 and KG 4 during 1917 and 1918. (Cowin Collection)

Although always overshadowed in the public eye by the Gotha name, the Fnedrichshafen G III equipped three of the eight German bomber wings at the time of the Armistice. Larger and heavier than the contemporary Gotha G IV, the G III carried a far heavier bomb load and seemed far less susceptible to the landing gear failures that constantly beset the Gothas. With a 3- man crew, the G III was powered by two 260hp Mercedes D IVs and could carry up to 3,300 Ib of bombs. Armed with two or three 7.92mm Parabellums, the G III had a top level speed of 87mph at 3,280 feet, along with a duration of 5 hours, implying a tactical radius of action, with full bomb load, of around 140 to 145 miles. Deployed initially in mid-1917, the G III and G IlIa went on to equip KG 1, KG 2 and KG 4 during 1917 and 1918. (Cowin Collection) The prototype Gotha G IV took to the air for the first time during December 1916. Larger than the preceding Gotha G III,

The prototype Gotha G IV took to the air for the first time during December 1916. Larger than the preceding Gotha G III,

Right and top right The story of the initial, faltering evolution of the early Junkers metal monoplanes is an enthralling one and was outlined in the author’s monogram on the subject in Profile Publications No 187. Suffice it to say here that while Reuter and his team followed Hugo Junker’s concept to the letter, their notions of construction engineering owed more to bridge building than aviation practice. They showed a marked reluctance to switch from steel to light alloy, despite the fact that Zeppelin had been using it since 1908, or thereabouts. Perhaps the finest example of this is the Junkers J.7 experimental single seat fighter first flown in early September 1917. In its initial form, as photographed in flight, the machine was an

Right and top right The story of the initial, faltering evolution of the early Junkers metal monoplanes is an enthralling one and was outlined in the author’s monogram on the subject in Profile Publications No 187. Suffice it to say here that while Reuter and his team followed Hugo Junker’s concept to the letter, their notions of construction engineering owed more to bridge building than aviation practice. They showed a marked reluctance to switch from steel to light alloy, despite the fact that Zeppelin had been using it since 1908, or thereabouts. Perhaps the finest example of this is the Junkers J.7 experimental single seat fighter first flown in early September 1917. In its initial form, as photographed in flight, the machine was an

Although seemingly out of place in this section, the experimental Fokker V.26, precursor to the EV/D VIII, is included to show how Anthony Fokker was to benefit aerodynamically from the Junkers company’s faltering production engineering practices. During the summer of 1917, it was becoming clear that the much-needed, armoured Junkers J I was suffering a production engineering bottleneck. Under pressure from on

Although seemingly out of place in this section, the experimental Fokker V.26, precursor to the EV/D VIII, is included to show how Anthony Fokker was to benefit aerodynamically from the Junkers company’s faltering production engineering practices. During the summer of 1917, it was becoming clear that the much-needed, armoured Junkers J I was suffering a production engineering bottleneck. Under pressure from on

Below and right Before and after images showing the prototype Junkers J.8 two seat close-support fighter and its production derivative, the Junkers Cl I. Work on the sole J.8 started in October 1917, aimed at providing a successor to the armoured Junkers J I. As it transpired, the J.8, with its 160hp Mercedes D III, had a top level speed of 116mph and impressed those that flew it at the first of the 1918 fighter trials. Not only did the J.8 lead directly to the Cl I production contract, but its development contributed greatly to solving many of the single seat J.7’s ongoing problems. Too late to have any effect in the air war, the 41 Junkers Cl Is completed stood up well, alongside their single seat Junkers D I when operated in the 1919 Baltic War. Powered by a 185hp Benz Bz IlIa, the Cl I had a top level speed of 118mph and a ceiling of 17,000 feet. Armament on later machines comprised two 7.92 Spandaus for the pilot, along with the flexibly-mounted 7.92mm Parabellum in the rear. (Junkers)

Below and right Before and after images showing the prototype Junkers J.8 two seat close-support fighter and its production derivative, the Junkers Cl I. Work on the sole J.8 started in October 1917, aimed at providing a successor to the armoured Junkers J I. As it transpired, the J.8, with its 160hp Mercedes D III, had a top level speed of 116mph and impressed those that flew it at the first of the 1918 fighter trials. Not only did the J.8 lead directly to the Cl I production contract, but its development contributed greatly to solving many of the single seat J.7’s ongoing problems. Too late to have any effect in the air war, the 41 Junkers Cl Is completed stood up well, alongside their single seat Junkers D I when operated in the 1919 Baltic War. Powered by a 185hp Benz Bz IlIa, the Cl I had a top level speed of 118mph and a ceiling of 17,000 feet. Armament on later machines comprised two 7.92 Spandaus for the pilot, along with the flexibly-mounted 7.92mm Parabellum in the rear. (Junkers)

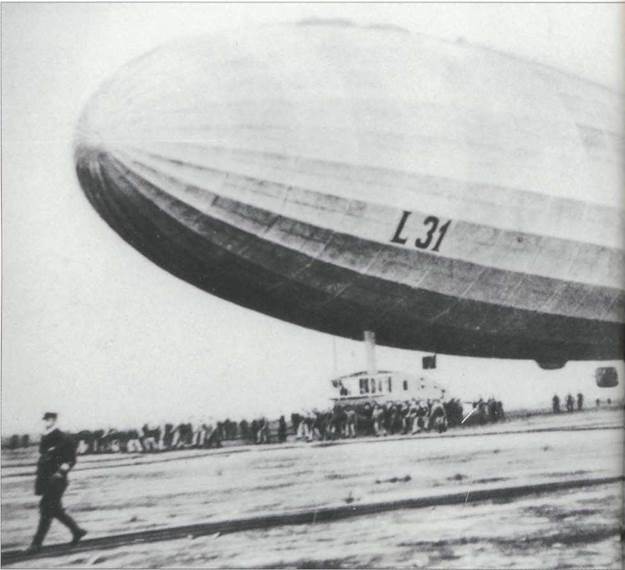

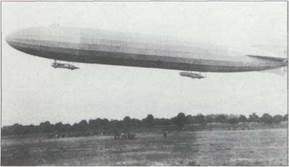

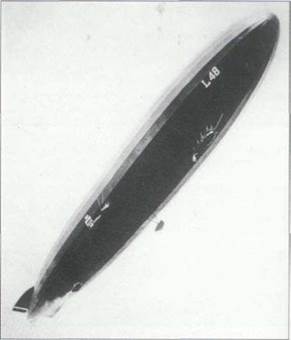

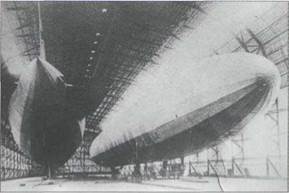

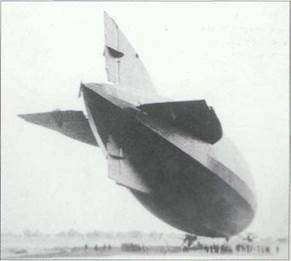

Although the value of aviation as a reconnaissance tool had initially been established by the German Army during its annual exercise of June 1911, its use remained confined to providing post-flight situation reports made to Corps, or Army-level Headquarter staff. For operational purposes, the aeroplane, with its relatively modest radius of action, was to undertake tactical reconnaissance, while the longer ranged airships would carry out strategic reconnaissance. This state of affairs was to remain essentially unaltered through to the outset of war. This mode of operating clearly had its limitations, prime among which was that the value of tactical information, such as train movement sightings, is a perishable commodity and becomes less useful the longer the time delay between sighting and reporting. Thus, at the outset of war, this perishability factor worked against the best efforts of the 33 deployed Field Flying Sections, or Feldflieger Abteilungen, each of which was equipped with six A (unarmed monoplane) or B (unarmed biplane) two seaters, because of the highly mobile nature of the battle lines during most of the first month. However, once the fighting had settled into its essentially static mode by the beginning of September 1914, then the value of the reconnaissance aeroplane rapidly came to the fore. This should be contrasted with the abysmal failure of the airship in operations, with four lost during the first month of the war, a setback that led directly to the army confining its airship fleet to night-only operations from then on. This limitation on the inherently low speed airship was extremely severe, curtailing its one major advantage over the aeroplane, that of range. In contrast, the German Navy’s airships, used for both reconnaissance and bombing, survived their initial operational deployment better and with fewer losses, but, of course, these craft were largely operating over the vast expanses of the Baltic and North Sea far removed from enemy defences and where they had room to better weather-out the unanticipated storm.

Although the value of aviation as a reconnaissance tool had initially been established by the German Army during its annual exercise of June 1911, its use remained confined to providing post-flight situation reports made to Corps, or Army-level Headquarter staff. For operational purposes, the aeroplane, with its relatively modest radius of action, was to undertake tactical reconnaissance, while the longer ranged airships would carry out strategic reconnaissance. This state of affairs was to remain essentially unaltered through to the outset of war. This mode of operating clearly had its limitations, prime among which was that the value of tactical information, such as train movement sightings, is a perishable commodity and becomes less useful the longer the time delay between sighting and reporting. Thus, at the outset of war, this perishability factor worked against the best efforts of the 33 deployed Field Flying Sections, or Feldflieger Abteilungen, each of which was equipped with six A (unarmed monoplane) or B (unarmed biplane) two seaters, because of the highly mobile nature of the battle lines during most of the first month. However, once the fighting had settled into its essentially static mode by the beginning of September 1914, then the value of the reconnaissance aeroplane rapidly came to the fore. This should be contrasted with the abysmal failure of the airship in operations, with four lost during the first month of the war, a setback that led directly to the army confining its airship fleet to night-only operations from then on. This limitation on the inherently low speed airship was extremely severe, curtailing its one major advantage over the aeroplane, that of range. In contrast, the German Navy’s airships, used for both reconnaissance and bombing, survived their initial operational deployment better and with fewer losses, but, of course, these craft were largely operating over the vast expanses of the Baltic and North Sea far removed from enemy defences and where they had room to better weather-out the unanticipated storm.

One of the early production Austrian Aviatik C I two seat reconnaissance machines, used on the Italian Front in late 1917. The serial, 37.40, just visible on the fuselage, follows the Austro – Hungarian practice of using the first 2-digit group to denote the production batch, while the last two numbers signify the individual aircraft’s place within the batch, in this case the 40th machine. Unlike the German system, there is no indication of the year in which construction took place. Sadly, little hard performance data survives on the type itself. (Cowin Collection)

One of the early production Austrian Aviatik C I two seat reconnaissance machines, used on the Italian Front in late 1917. The serial, 37.40, just visible on the fuselage, follows the Austro – Hungarian practice of using the first 2-digit group to denote the production batch, while the last two numbers signify the individual aircraft’s place within the batch, in this case the 40th machine. Unlike the German system, there is no indication of the year in which construction took place. Sadly, little hard performance data survives on the type itself. (Cowin Collection)

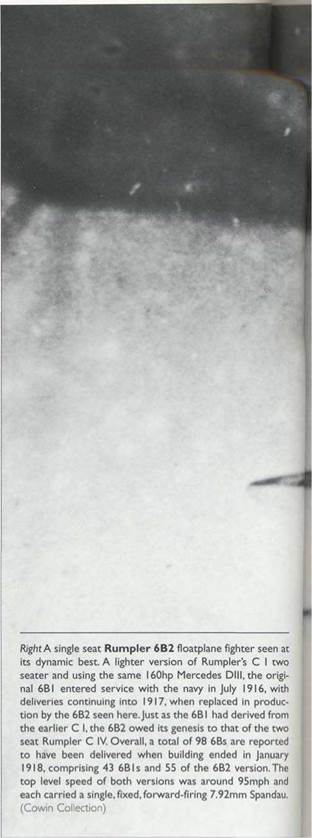

the problem by giving the nose gunner an unlimited forward field of fire, the inherent drawbacks of added weight and drag that went with the pusher layout reduced speed and agility significantly. Thus, unless a pusher had an initial height advantage, enabling it to dive on its prey, it was unlikely ever to be able to close on the enemy. As the French saw it, what was needed was to remove the observer altogether and simply fix the gun where the pilot could reach it. Oh, and while doing this, why not fix the gun so that it could fire directly ahead through the propeller arc of a small, fast single seater, of which the French had many? The concept certainly had appeal, chief of which was the single seater’s significant speed advantage and, therefore ability to close quickly.