Preparations

On 3 August 1914, Germany, along with the

Austro-Hungarian Empire, collectively known as the Central Powers, declared war upon France.

On the following day, Britain was drawn in thanks to its treaty obligations to Belgium, as that country was trampled by German invaders. Thus, within a matter of hours, Europe had become embroiled in a conflict that was to grow into one of unprecedented scale and intensity, a war in which millions were to die. It was also the first war ever, thanks to aviation, where the fighting and its associated destruction could be visited on civilian populations sometimes well over a hundred miles from the front lines, let alone the air bases from which the bombers departed and returned.

Military aviation in early August 1914 was still very much in its infancy with only a few nations having anything resembling a coherent air force. Of this handful of nations Germany had the largest number of operationally deployed aircraft, with 258, excluding kite balloons and a handful of airships, the majority of which were sited on the Western Front. Facing the Germans, France and Britain could only muster 156 and 63 heavier – than-air machines respectively, at the front. Further, it is generally acknowledged that, at this time, the German forces were better organised. It should be emphasised that these remarks apply to the German Imperial Army Air Service, as opposed to the German Imperial Naval Air Service, which was not only much smaller, but at this time was centred around a largely still to be furnished airship fleet as its primary asset, the aeroplane seen as very secondary in terms of operational importance. Of the other initial belligerent nations, only the Austro – Hungarians had a tiny, but reasonably organised army air arm equipped with land-based aircraft, while the Hungarian Navy largely operated small flying boats. Generally, these machines were of Austrian design and manufacture and were of fairly mediocre capability. The one exception were the Lohner flying boats, that were widely copied or licensed in Italy, France and Germany. From all surviving documentation, what Russian military aviation there was at the outset of World War I was both pitifully scant and unorganised.

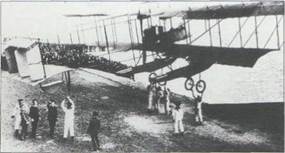

Above right Anthony Fokker, pilot and aircraft manufacturer, had the entrepreneur’s innate gift for getting it right in his business decisions. An early example of this was his setting up of the Fokker Flying School at Doberitz, close to Berlin in late 1912. When the German Army announced their plan to sub-contract flying training to civilian organisations in 1912, Fokker grasped the opportunity of establishing close personal contact with the the future leaders of German military aviation. Although Fokker left the day-to-day training chores to his flying instructors, he was the school’s Chief Flying Instructor and Examiner. Fokker is seen here sitting on the axle of one of his Fokker Spin two 8 seaters. amid one of his early military intakes. (Cowin Collection)

So much for quantitative analysis. Here, it is pertinent to make a qualitative assessment. At this time, virtually all of the world’s air arms operated a motley assortment of aircraft types and such developments as type and even role standardisation were some way off. Perhaps the only meaningful yardstick to apply in assessing an air arm was the size of its flight training effort. In this, only France and Germany are worthy of consideration, with Germany just edging ahead in the annual numbers of pilots and observers produced. The real build-up in German military heavier-than-air aviation commenced in 1911, 37 machines bought by year-end. During 1912, emphasis was given to the training of pilots and observers, the army’s limited facilities augmented by the contracting of civilian flying schools, mainly off-shoots of the aircraft manufacturers, to meet the planned growth in throughput.

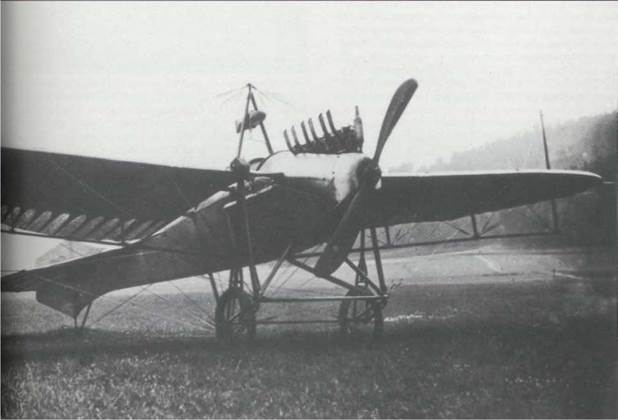

Below The Etriche Taube two seater of Austrian origin first flew in November 1909 and was adopted by the German military in 1911 as their standard reconaissance and training type. Most were built under licence in Germany by Rumpler. They were withdrawn from front line service by mid-1915. This is a 1912 Taube fitted with a lOOhp Daimler D. I. giving a top level speed of 7l mph. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

|

|

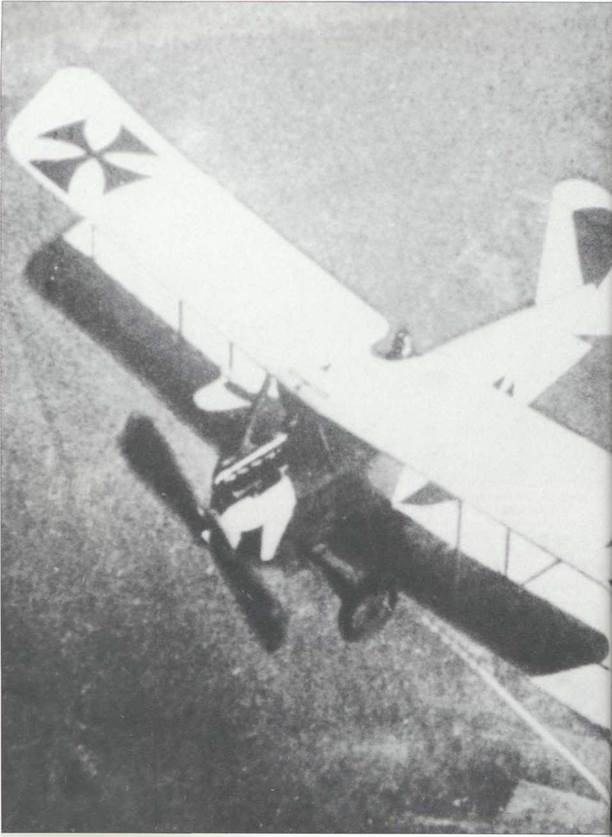

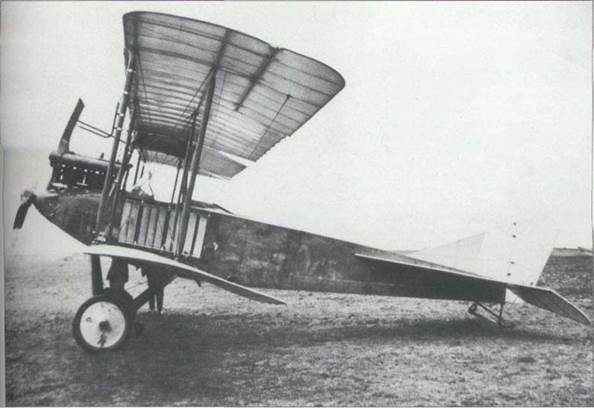

Above One of the so-called Steel Taubes, built by LFG Roland during 1914. Employing a steel tube structure in place of the Etrich’s original wooden one, the lOOhp Daimler having now become a lOOhp Mercedes D I. Despite these changes, performance, or at least the 71 mph top level speed appears to have changed little. Note the retention of wing warping and the distance between pilot in the rear and the front seated observer, something that could not have helped in-flight communications. (Cowin Collection)

BelowThe Albatros WMZ of 1911 was generally considered to be the German Imperial Naval Air Service’s first practical seaplane, but aeroplanes were to take a back seat to airships in pre-war naval plans. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

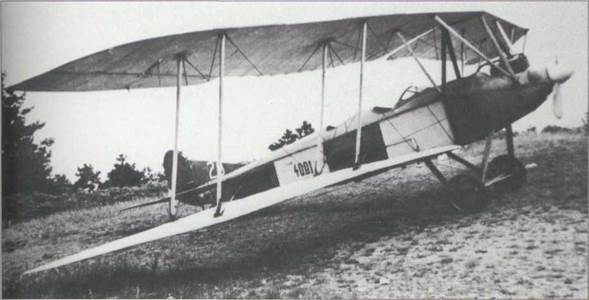

Above right The Gotha LE-3, military designation Gotha A I of 1914, was yet another minor variation on the Etrich Taube theme. Gotha built 20 of these two seaters with the army serials A79/I4 to A9I/I4, Al 19/14 to AI25 and AI37/I4 to A142/14. Employing the lOOhp Mercedes D I, range for the 10 machine was quoted as 239 miles. (Cowin Collection)

Bottom This Pfalz-built Otto Biplane, seen here in happier, prewar times, was the only aircraft available in German East Africa at the outbreak of war and as such was pressed into military service, along with its pilot, Bruno Buckner. (Cowin Collection)

Opposite, top First flown in early 1914, this Albatros two seater, along with a slightly smaller version, was adopted by the army as the Albatros B I and B II, respectively. Between them, these two unarmed machines provided most of German aerial reconnaissance capability well into 1915.Thanks to their relatively viceless handling characteristics, both the B I and B II stayed in production, albeit relegated to the training role, into

|

|

1917. Power for both aircraft was either a lOOhp Mercedes, or a IlOhp Benz Bz I, giving the pair a top level speed of around 65mph at sea level. (Cowin Collection)

Below Little valid information survives on this Austrian Army Air Service-operated Lloyd C I of early 1914 design origins,

other than that it was powered by a l20hp Austro-Daimler and that it set a new altitude record of 21,709 feet on 27 June 1914. Only built in small numbers, the type led to the Lloyd C II through C V series, the workhorses of both the reconnaissance and training units of the Austro-Hungarian Air Service; reconnaissance, in the early years, being the only real function of military aircraft. (Cowin Collection)

|

|