The Lofty Overview

Although the value of aviation as a reconnaissance tool had initially been established by the German Army during its annual exercise of June 1911, its use remained confined to providing post-flight situation reports made to Corps, or Army-level Headquarter staff. For operational purposes, the aeroplane, with its relatively modest radius of action, was to undertake tactical reconnaissance, while the longer ranged airships would carry out strategic reconnaissance. This state of affairs was to remain essentially unaltered through to the outset of war. This mode of operating clearly had its limitations, prime among which was that the value of tactical information, such as train movement sightings, is a perishable commodity and becomes less useful the longer the time delay between sighting and reporting. Thus, at the outset of war, this perishability factor worked against the best efforts of the 33 deployed Field Flying Sections, or Feldflieger Abteilungen, each of which was equipped with six A (unarmed monoplane) or B (unarmed biplane) two seaters, because of the highly mobile nature of the battle lines during most of the first month. However, once the fighting had settled into its essentially static mode by the beginning of September 1914, then the value of the reconnaissance aeroplane rapidly came to the fore. This should be contrasted with the abysmal failure of the airship in operations, with four lost during the first month of the war, a setback that led directly to the army confining its airship fleet to night-only operations from then on. This limitation on the inherently low speed airship was extremely severe, curtailing its one major advantage over the aeroplane, that of range. In contrast, the German Navy’s airships, used for both reconnaissance and bombing, survived their initial operational deployment better and with fewer losses, but, of course, these craft were largely operating over the vast expanses of the Baltic and North Sea far removed from enemy defences and where they had room to better weather-out the unanticipated storm.

Although the value of aviation as a reconnaissance tool had initially been established by the German Army during its annual exercise of June 1911, its use remained confined to providing post-flight situation reports made to Corps, or Army-level Headquarter staff. For operational purposes, the aeroplane, with its relatively modest radius of action, was to undertake tactical reconnaissance, while the longer ranged airships would carry out strategic reconnaissance. This state of affairs was to remain essentially unaltered through to the outset of war. This mode of operating clearly had its limitations, prime among which was that the value of tactical information, such as train movement sightings, is a perishable commodity and becomes less useful the longer the time delay between sighting and reporting. Thus, at the outset of war, this perishability factor worked against the best efforts of the 33 deployed Field Flying Sections, or Feldflieger Abteilungen, each of which was equipped with six A (unarmed monoplane) or B (unarmed biplane) two seaters, because of the highly mobile nature of the battle lines during most of the first month. However, once the fighting had settled into its essentially static mode by the beginning of September 1914, then the value of the reconnaissance aeroplane rapidly came to the fore. This should be contrasted with the abysmal failure of the airship in operations, with four lost during the first month of the war, a setback that led directly to the army confining its airship fleet to night-only operations from then on. This limitation on the inherently low speed airship was extremely severe, curtailing its one major advantage over the aeroplane, that of range. In contrast, the German Navy’s airships, used for both reconnaissance and bombing, survived their initial operational deployment better and with fewer losses, but, of course, these craft were largely operating over the vast expanses of the Baltic and North Sea far removed from enemy defences and where they had room to better weather-out the unanticipated storm.

With the early onset of the largely static trench warfare that so characterised World War I, the Germans were quick to realise another role in which the two seat aeroplane could be employed, namely that of close air support for their infantry. In these missions, the machine’s observer was used to harass the enemy’s front lines by rifle fire and dropping light bombs, the latter being done fairly haphazardly at first while awaiting the development of an effective aiming method. Such was the clamour from the ground troops for close air support, that a further requirement soon arose for a specially dedicated ground attack machine, the C1 class aircraft, with their armour cladding aimed at reducing vunerability to ground fire. In parallel with these close air support tasks, the Field Flying Sections were, thanks to advances in airborne radio telephony, beginning to undertake another important function, that of directing fire and spotting fall of shell for the artillery. The possible doubts about the value of the ‘eye in the sky’ that may have been voiced during the first weeks of the war had long since vanished, the two seaters were here to stay.

Thus, by the summer of 1915, the modestly performing two seaters with which the army entered the war had evolved into the more powerful and armed C class machines, capable of undertaking a variety of offensive and defensive tasks at both high and low levels. Such had been the efficacy of the aeroplane in providing invaluable tactical information to the commanders in the field that, as early as the close of 1914, the French in particular were being driven to produce a gun-carrying counter to these ever-probing German aerial incursions.

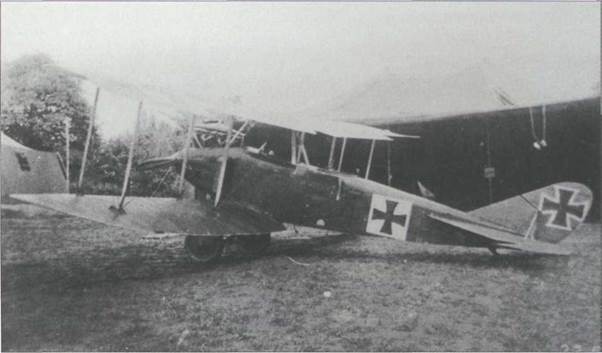

Left An admirable air-to-air image of a Rumpler 5A, military designation C I, an armed and more powerful derivative of the company’s B I. First flown towards the end of 1914, the Rumpler C I was powered by a l6Ohp Mercedes D III, giving it a top level speed of 94mph at sea level. The C I’s handling docility was matched by what was, for its time, an impressive high altitude ability, the operational ceiling being quoted as 16,600 feet. This translates into the machine being able to overfly enemy territory

|

largely immune from interception unless caught by an enemy standing patrol already at or above its own altitude. For defence at lower altitudes, the C I’s rear seated observer was equipped with a flexibly-mounted 7.92mm Parabellum gun, later added to by providing the pilot with a fixed, forward firing 7.92mm Spandau, useful for trench strafing, on the C la. Although the actual production figures have not survived, the C I was known to have been built in sustantial numbers by Rumpler and four sub-contractors, with around 250 serving in operational units in October 1916. Allowing for attrition and other factors, it would be safe to assume total C I build to be well in excess of 500 machines. The C I pictured here belonged to the Schleissheim-based advanced flight training unit tasked with bringing trainee crews up to full operational standard. (Cowin Collection)

Bottom The Albatros B I typified the fragility of the early reconnaissance machines fielded by the armies on both sides of the line and on all fronts. Nonetheless, the vital importance of these machines was to be displayed for the all world to see during the five-day Battle ofTannenberg that commenced on 26 August 1914, during which the Russians were rebuffed, with the loss of 30,000 dead and 90,000 captured.

Although initially designed as a high performance two seater, the Gotha LD-5 was rejected for field service as other than a single seat advanced trainer and even in this role, its small wing area and consequent high wing loading would ensure that it was confined to operating from the longest of available

|

|

airstrips. First flown in December 1914, the LD-5 used a lOOhp Oberursel Ur I, but no other useful performance data survives. The real mystery surrounding the LD-5, however, is how Gotha were permitted to build no less than 13 of these fairly pilot- unfriendly looking brutes. (Cowin Collection)

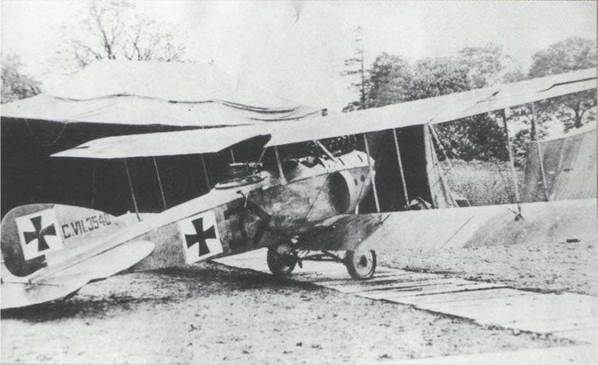

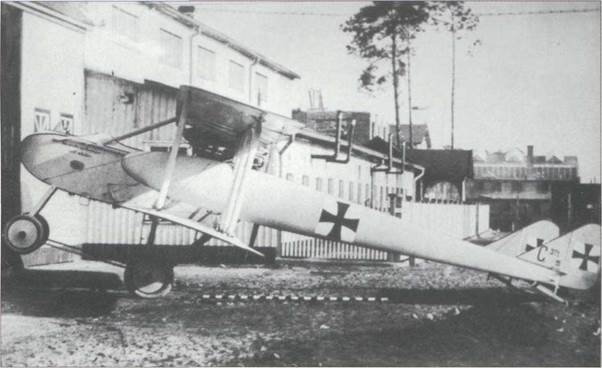

Opposite, top This unarmed Aviatik B II, serial 34.08, was built by the Austrian-based branch of the company for service with the Austro-Hungarian forces, powered by a lOOhp Mercedes. Of late 1914 origins, only a relatively small number of B IIs were produced, the type being quickly superseded by the more powerful, cleaner and armed Aviatik C I. As was often the case, once relegated from front-line service, the type found a second career with advanced flying training units, the Aviatik B II known to have served in this role with FEA 9 at Darmstadt during 1916. (Cowin Collection)

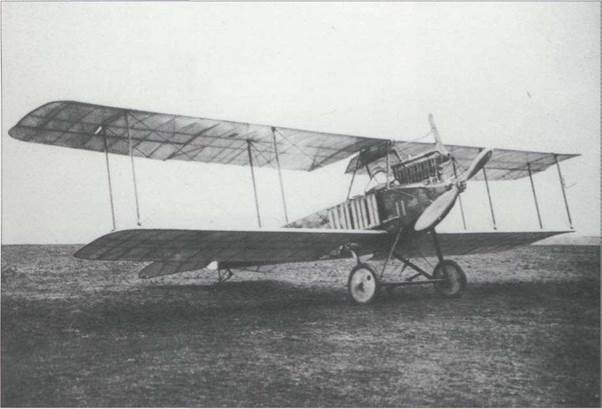

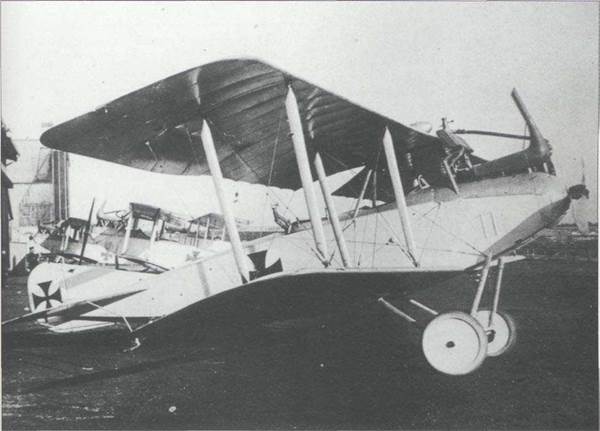

Below Only ten of these 1915 two seat Gotha B Is were produced, just sufficent to equip a single Field Flight Section, although no evidence of their deployment, if ever, has survived. Using a l20hp Mercedes D la, the LD-7 to give its design bureau designation, had a top level speed of 77.5mph, with a range of 330 miles. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

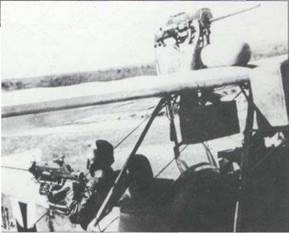

Above, rightThis Albatros C I observer demonstrates just how crude manual bomb dropping could be in the late spring of

1915. The weapon he is posing with is the standard 10 Kg/22lb high explosive bomb introduced the previous year. By mid-

1916, such weapons would be fitted to remotely released, underwing bomb racks for providing close air support to the infantry. (Cowin Collection)

Right The Albatros C I, deployed operationally from the spring of 1915, soon built a reputation for its ease of handling and general robustness. During its two year production life, the C I

|

|

underwent a series of changes, being fitted with ever more powerful engines starting with the 150hp Benz Bz III and ending with the l80hp Argus As III. Along with these changes of engine, the position of the radiator moved around, starting on the fuselage flank in the C I, but moving to drape from the upper wing’s

|

|

|

centre section leading edge, as here on this C la. Top level speed of the C la was 87mph at sea level, with a ceiling of 9,840 feet. The armament comprised a single, flexibly-mounted 7.92mm Parabellum in the rear cockpit. (Cowin Collection)

Oops! The Albatros C I of Lt Maass, Fl Abt 14, after nosing over in the snow at Subat on the Eastern Front during January 1916.The standard practice appears to have been that any new type found its way, initially, to the Western Front, then the Eastern Front, where the opposition was likely to be less fierce. Finally, when considered operationally obsolete, the machine would frequently pass into the training role. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

Lohner of Austria, besides producing their admirable line of small, agile flying boats, also built a series of land-based, reconnaissance two-seaters for the Austro-Hungarian Air Service. In

stark contrast to their flying boats, these B and C class designs, spanning the years 1913 to 1917, proved mediocre performers and, in consequence, each variant was only built in small numbers. The 1915 Lohner B. VII, 17.00,seen here, despite its 160hp Austro-Daimler, could only achieve a top level speed of 85 mph at sea level. As in this case, despite their B class designations, many two seaters were retrospectively fitted with a gun in the rear seat, thus converting them, effectively, into C types. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

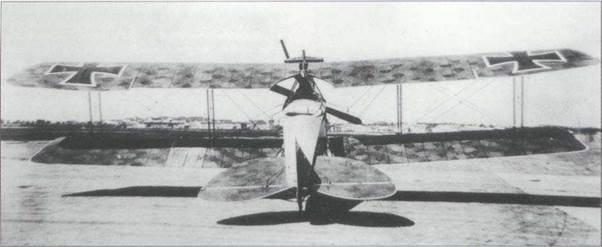

Below The intriguing twin-boom fuselaged Ago C II of late summer 1915 origins employed the same basic layout as the Ago C I, but used the 220hp Benz Bz IV. Only built in relatively modest numbers, the Ago C II began to be deployed at the end of 1915 and operated on the Western Front. This C II, 37I/I5, is a late production example. The type’s top level speed was quoted as 86 mph at sea level. (Cowin Collection)

A fine shot of the rarely pictured two seat, pusher-engined Friedrichshafen FF37, or C I to give it its military designation. Of early 1916 vintage, the experimental FF37s general layout appears to have been influenced by that of the Royal Aircraft Factory’s F. E2, following the British practice of seating the gunner in the nose, forward of the pilot. The FF37 was destined never to progress beyond the prototype stage. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

This close-up of the crew accommodation of a Hansa – Brandenburg C I can be dated to late 1916 or after, thanks to the presence of the pilot operated 8mm Schwartlose machine gun over the upper wing. The ring mounting of the observer’s flexibly-mounted Schwartlose is just visible to the left of his forearm. This type was built exclusively in Austria by Hansa-Brandenburg’s local subsidiary and the aircraft’s Austro – Hungarian Air Service serial, 64.07, further identifies it as being the seventh of a sub-contracted production batch built by UFAG. Most C Is employed a l60hp Austro-Daimler. Operationally deployed initially in early 1916, the C I’s modest

87mph top level speed at sea level may not have impressed, but its high altitude capability did. With an operational ceiling of 19,030 feet, the C I, once at height was largely impervious to interception. This helps explain why the type was never quite usurped by the later and faster Aviatik C I and remained operational until war’s end. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

|

BelowWhereas the Ago C I to C III had all been twin-boom fuselage designs, their C IV was of fairly conventional layout, the only novelty the pronounced degree of taper on the one – and-a-half bay wings. Generally well regarded by its crews, the C IV used a 220hp Benz Bz IV, giving it a top level speed of 119mph at 4,000 feet; normal range was 497 miles. Production bottlenecks, attributed to wing assembly, limited deliveries to around 70 operational examples. This is an early example, with balanced rudder and no fixed fin. (Cowin Collection)

Below A Lloyd C II of the Austro-Hungarian forces operating at the southern end of the Eastern Front in 1916. Seen here being re-assembled after being rail freighted to the front, little more information concerning the aircraft’s, crew’s or unit identity survives. However, photographs reveal that shortly after this image was taken, the machine nosed-over during the subsequent attempted take-off. (Cowin Collection)

Below This example of a late production Ago C IV was clearly cosidered something of a trophy by its No 32 Squadron, RFC, captors. This machine, C8964/I6, captured on 29 July 1917, was flown to Britain for detailed evaluation, but crashed on 17 August 1917. Note Ago’s adoption of a Sopwith style fixed fin on the later C IVs. (British Official/Crown Copyright)

Above Rumpler C I, 53/16, powered by a l60hp Mercedes D III. Armed with a fixed, pilot-aimed 7.9mm Spandau, along with the observer’s 7.92mm Parabellum, the Rumpler C I was considered by many to be the best and most reliable of all C types produced. Top level speed of the machine was 94mph at sea level, while the service ceiling was around 16,600 feet. Normal range was given as 336 miles. (Cowin Collection)

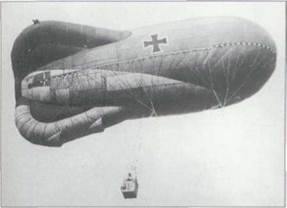

Opposite, top The tethered, or kite balloon had been seen as a valuable tactical reconnaissance tool long before the aeroplane’s arrival and the German army continued to employ them right 18 up until the Armistice. Although at first sight so vulnerable, the

employment of in-depth flak and other defences around each balloon made them particularly thorny prey for enemy attackers. Capable of day or night operation, the German Type AE balloon, seen here, was introduced during the early summer of 1916. Copied from the French Type M, the AE could be flown in winds of up to 55mph. With its greater lift, the AE could loft a considerable amount of gear, as well as its observer, within its basket, including radio telephony equipment and a long distance camera. Thus, on the AE, the parachute fitted was of sufficent size to ensure the safe return not just of the observer, but of the whole basket’s contents. At the end of 1916, no less than 128 single balloon sections, or Feldluftschiffer Abteilungen. were operationally deployed, usually being fielded in a well spread group of three to aid triangulation. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

Below Deployed operationally for the first time towards the end of 1916, the Albatros C III was built in larger quantities than any other of the firm’s C types. The C III, with its l60hp Mercedes D III had an undistinguished top level speed of 82mph at sea level. The initial single, flexibly-mounted 7.92mm gun was later supplemented by another, fixed forward-firing weapon for the pilot. In spite of its robust construction that allowed it to withstand considerable combat damage, the C III compared poorly in terms of performance with the DFW CV that was to become the main workhorse of the two seater units from late 1917 until the end of the war. (Cowin Collection)

This Albatros C III has clearly landed on the wrong side of the lines and provides the focus of interest for a number of French civilians, while the soldier in the foreground and close to the photographer appears more concerned with grooming his moustache. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

|

Overleaf, top An excellent rear-on image of an Albatros C III, showing the standard multi-colour hexagonal lozenge camouflage adopted from January 1918 for use by all reconnaissance and fighter types in service with the German Imperial Army Air Service. (Cowin Collection)

|

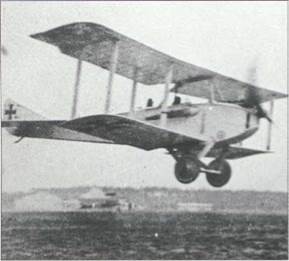

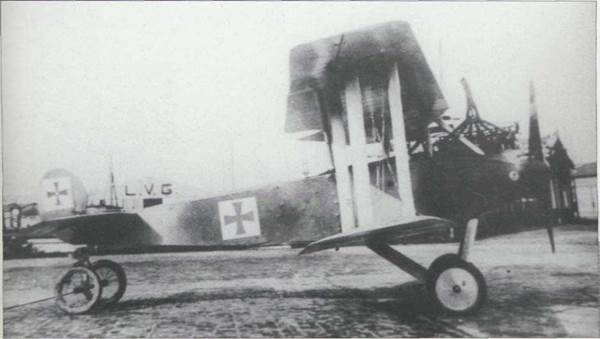

Below A dramatic ground-to-air image of the 1916 LVG C IV. This type proved to be another reconnaissance design that failed to progress beyond the developmental stage. Powered by a 220hp Mercedes D IV, the LVG C IV appears to have been little more than a slightly scaled-up, more powerful variant of the widely used LVG C II. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

Opposite, below The LFG Roland C II of exceptionally clean appearance made its debut in October 1915 and stayed in frontline service until the autumn of 1917. Powered by a l60hp Mercedes D II, the C ll’s top level speed was IO3mph at sea level. Thanks to its relatively short span, low aspect ratio wings, its high altitude performance was limited to a modest ceiling of 13,100 feet. This said, it should be noted that the RFC ace, Albert Ball cites this machine as being the best of the German two seaters with very effective fields of fire to the front and to the rear. This is an early production example, serving with Fl Abt A 227 at Lille in the autumn of 1916.The crew members are Lt Stuhldreer, pilot, sitting on the inboard upper wing, along with Lt Allmenroder, 20 observer, astride the port wheel. (Cowin Collection)

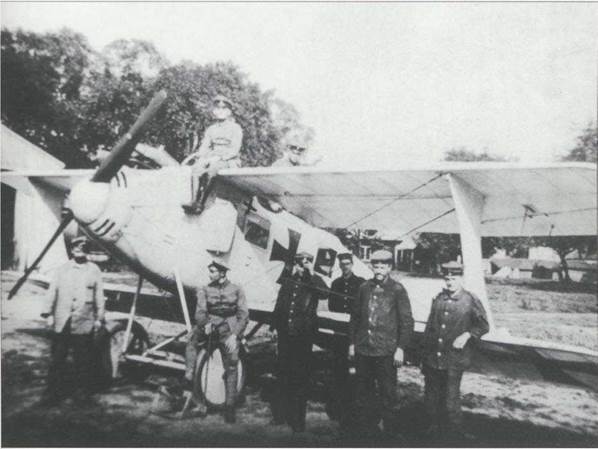

Top, right Built in substantial numbers, the Albatros C VII entered operations near the close of 1916. Hastily developed to circumvent the engine-related unreliability being experienced by their CV, the CVII used the 200hp Benz Bz IV. With this engine, the CVII proved reliable and equally at home doing relatively high level reconnaissance at its ceiling of 16,400 feet, or doing its infantry support task of strafing trenches with its short range 200lb bomb load. At least 350 Albatros C VIIs had been delivered by the parent company and its two sub-contractors by February 1917. (Cowin Collection)

Rear aspect of a late production LFG Roland C II that complements the front view opposite. The salient difference between early and late machines is the increase of both fin and rudder area. The machine seen here belonged to the the Bavarian Fl Abt 292 and was photographed in early 1917. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

OverleafThe Rumpler C III two seater was a development of the widely used C I with the one major difference that it lacked any form of fixed fin. In the event, this deletion was to be the design’s downfall. Using a 220hp Benz Bz IV, the C III entered service in early 1917. but was withdrawn from operations within a month or so following a spate of crashes, attributed to the machine’s lack of adequate latitudinal, or

|

|

|

|

yawing control at low speed. It is reported that around 75 C Ills had been delivered by Rumpler prior to the type’s withdrawal from service. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

If the Rumpler C III had proven to be a disaster waiting to happen, its successor from the same stables was just the reverse. Powered by a 260hp Mercedes D IVa, the Rumpler C IV followed closely upon the C III, ensuring that the firm was in a position to continue producing two seaters almost without interruption during the spring of 1917.The C IV, with its top level speed of IO9mph at sea level, combined with a superb high altitude capability of 21,000 feet saw the C IV providing stalwart service through to the cessation of hostilities. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

Opposite page Germany’s leading World War I fighter ace, Baron Manfred von Richthofen, went to war in August 1914 as a young lieutenent in a lancer regiment, aged twenty two. Only at the close of 1914 did he succeed in transferring to the Army Air Service, where, as with many other fighter aces to be, he cut his aviation teeth first training and then operating as an observer. Indeed, it is generally held that although officially unconfirmed, his first ‘kill’ was made against a Farman from the rear of a two seater. Even after gaining his wings on Christmas Day 1915, the young flier was to remain piloting two seaters for much of 1916. It was during this period that he was to meet the father of German fighter tactics, Oswald Boelcke. Clearly something about Richthofen impressed Boelcke, who subsequently invited him to join his newly formed fighter squadron, 22 or Jagdstaffel 2. Here, Richthofen was one of four to fly the unit’s first mission on 17 September 1916, setting him on a course that was to see him credited with 80 victories, before he and his scarlet Fokker Dr I were to meet their end on 21 April 1918. The Baron scored official victory number 16 on January 4 1917 and received the Pour Le Merite twelve days later as the new leader of Jasta 2 (at that time the medal was awarded for 16 kills). The picture captures the young Baron about to climb into his personal transport, which, ironically, was the sole prototype Albatros C IX, presented to him after its failure to gain full operational acceptance. (Cowin Collection)

The sole Albatros C IX of early 1917 was one of a number of prototypes submitted against the need for an armoured close air support type, shortly to be given their own Cl designation to identify their specialised ground attack capability. As it transpired, the Junkers J I was to sweep all competition aside and, thus, the lone Albatros passed into the hands of Baron Manfred von Richthofen, for use as his personal transport. The 160 hp Mercedes D III powered C IX had a top level speed of 96.3mph. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

Another of the losing designs for the the armour clad, ground attack requirement was this one-off Zeppelin-Lindau Cl I. First flown on 3 March 1917, this l60hp Mercedes D III two seater was the brainchild of a design team headed by Claudius Dornier and used the light alloy construction he was pioneering with his series of giant flying boats, dealt with in the next chapter. The Dornier Cl I’s top level speed was IO2mph at sea level. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

|

|

Above The cfear wfnner of the early f91 7 cfose air support type competition was the extremely well armoured Junkers J.4, confusingly given the military designation, not of Cl I, but J I. For a 200hp Benz Bz IV powered aircraft, the J I was both big and heavy, built to withstand the withering close-range defensive fire likely to be encountered, ranging from rifle to heavy machine gun. First flown on 27 January 1917, the J I employed the Junkers pioneered thick aerofoil wing that provided more lift than a thin sectioned wing of comparable area. With a top level speed of 96mph at sea level, the J I was neither fast nor agile. However, it was very effec

tive in its role and much beloved of its crews, whose sense of wellbeing owed much to the demonstrable protection provided by the machine’s armour cladding. From the offensive viewpoint, the J I was fairly well equipped for its mission, carrying two, pilot-aimed, fixed forward firing 7.92mm Spandau, plus the observer’s 7.92mm Parabellum, along with underwing racks for light bombs. The J I’s biggest problem lay not so much with the machine, but its makers, who were better researchers than production engineers: thus, initial deployment did not occur until September 1917 and despite the clamour for more, only 227 had been built by the time of the Armistice in November 1918. (Cowin Collection)

Opposite, below Probably one of the best of the C types, DFW’s CV embodied all of the neatness and efficiency of the C IV that had made its service debut early in 1916, but benefitted from the greater power of a 200hp Benz Bz IV. This gave the machine a top level speed of 97mph at 3,280 feet, while the C Vs operational ceiling was 16,400 feet. Built not just by DFW, but by four other sub-contractors, the C V was probably the best allrounder of the German two seaters with just under 1,000 being in operation on every front at the end of September 1917. Armament comprised the standard fixed, forward-firing and flexibly-mounted 7.92mm guns, plus light bombs. Shown here is a DFW C V of Fl Abt (A) 224 at Chateau Bellingcamps photogaphed on 22 May 1917. (Cowin Collection)

Lieutenants Leppin and Basedow, of Fl Abt 234, pose beside Aviatik-built DFW C V just prior to the launch of the great German offensive of late march1918.Aimed at thrusting through to the French coast to sever contact between the British and French armies, the role of the Field Flight Sections in providing tactical information was crucial in the run-up to the 21 March zero hour. To this end, 49 Field Flight Sections, or approximately one third of Germany’s total two seater assets were directly deployed in support of the offensive. The DFW C V was the mainstay of the field Flight Sections until into the summer of 1918 and the operational arrival of the DFW CV1. (Cowin Collection)

This LVG C V two seater has been flown to England for test and evaluation after its capture. First flown in early 1917, the LVG C V was deployed operationally during the summer of 1917.A sturdy design, the machine was well liked by its crews despite the somewhat restricted visibility it offered to both pilot and observer. Powered by a 200hp Benz Bz IV, the CV had a top level speed of IO5mph at sea level, along with an impressive ceiling of 21,060 feet. Pilot and observer both had a 7.92mm machine gun. While no precise figures survive, several hundred LVG C Vs are known to have been built. (British Official/Crown Copyright)

|

|

One of the early production Austrian Aviatik C I two seat reconnaissance machines, used on the Italian Front in late 1917. The serial, 37.40, just visible on the fuselage, follows the Austro – Hungarian practice of using the first 2-digit group to denote the production batch, while the last two numbers signify the individual aircraft’s place within the batch, in this case the 40th machine. Unlike the German system, there is no indication of the year in which construction took place. Sadly, little hard performance data survives on the type itself. (Cowin Collection)

One of the early production Austrian Aviatik C I two seat reconnaissance machines, used on the Italian Front in late 1917. The serial, 37.40, just visible on the fuselage, follows the Austro – Hungarian practice of using the first 2-digit group to denote the production batch, while the last two numbers signify the individual aircraft’s place within the batch, in this case the 40th machine. Unlike the German system, there is no indication of the year in which construction took place. Sadly, little hard performance data survives on the type itself. (Cowin Collection)

|

|

Overleaf The Albatros C XII long range reconnaissance machine made its debut in the summer of 1917 and initial service deliveries commenced towards the end of that year. Power was provided by a 260hp Mercedes D IVa, giving the aircraft a top level speed of IO9mph at sea level. The service ceiling for the C XII was cited as 16,400 feet. The standard 25

armament of single fixed and flexible 7.92mm guns was carried. This is the prototype, CI096/I7. Albatros, plus three subcontracting companies were involved in producing these machines, but quite how many is unknown. (Cowin Collection)

537 Cl Illas. Incidentally, the reason for the small number of Cl Ills produced had nothing to do with the aircraft, but rather it was because it used a l60hp Mercedes D III, which was urgently needed to power the Fokker D VII. The standard two-gun armament, one for each crew member, was fitted. (Cowin Collection)

Below The Hannover Cl Ilia of 1918 was a relatively minor development of the company’s Cl II and both used the same l80hp Argus As III. Both the Cl II and III series of ground attack and escort fighters endeared themselves to their crews thanks to a number of useful attributes. From the pilot’s viewpoint, visibility was excellent both forward and downward, while the quaint biplane tail, with its narrow span and position, provided the observer with an improved rearward arc of fire. Top level speed of the Cl IlIa was I03mph at sea level, while the machine had a range of 285 miles. Agile and robust, the first of 439 Cl IIs entered service in December 1917, followed by 80 Cl Ills and

Right August Rottau, seen here on the right, who held the rank of sergeant pilot, came from flying on the Eastern Front to join Battle Section, or Schlachtstaffel 37 in February 1918. Holder of the Golden Military Cross of Merit, Rottau was credited with two confirmed ‘kills’.AIongside Rottau in this photograph is his observer, Lt Perleberg. In German bomber and reconnaissance units, the observer’s status was higher, with the pilot considered akin to a mere chauffeur. The task of the Battle Sections, of which there were 38 in March 1918, was to provide close, low-level air support at, and immediately behind, the enemy’s front. (Cowin Collection)

|

|