The Promises In Prospect

|

W |

ithout question, Germany ranked a poor second to France in terms of aircraft development at the start of World War I, as for that matter, did all the other nations, including Britain. What happened during the next four years was of extreme significance. The cash injections made by the major belligerent nations boosted the size of the aircraft and aero-engine building industry enormously, but, perhaps surprisingly, did little

to further the technical development of aircraft, although aero-engine development was to see appreciable benefits. Indeed, even the French seem to have made little or no progress in aerodynamics during this period, a charge that could equally be laid against the British, Italians and Russians. At the time of the Armistice on 11 November 1918, one country and one country alone could point to having made any real advances in airframe development.

That country was Germany.

The men that pioneered these German advances were few, but their work was to leave an indelible mark in the annals of aeronautical development. It is to the efforts of men such as Hugo Junkers and later Adolf Rohrbach, who jointly produced the modern cantilevered monoplanes that eventually killed off the biplane in the early 1930s, that we must look for genuine progress. Recognition must also be paid to those such as Claudius Dornier and Oskar Ursinus, whose early use of alloys or other construction methods contributed to the overall advance. It is to these men of vision that this section is dedicated.

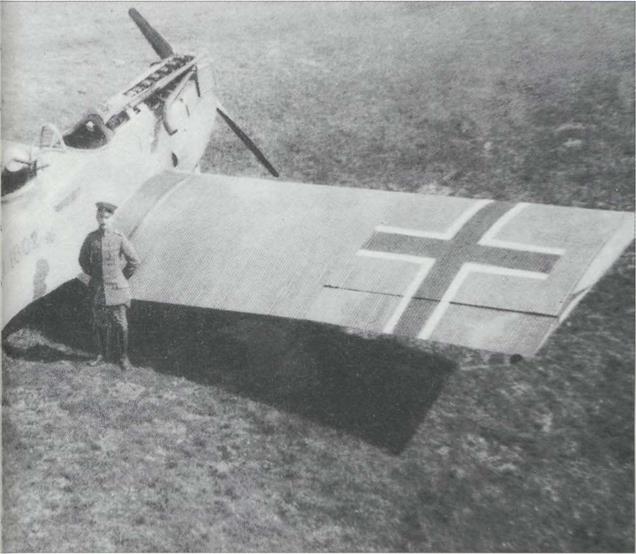

Photographed in a Belgium field on 21 January 1919, this allmetal Junkers D I was still deemed to be basically airworthy after being abandoned in the open for more than three months. Four Fokker D VIIs on the same site had deteriorated beyond repair. (Peter M. Grosz)

Below The monoplane was far from being a novelty, when the Junkers J. I was rolled out in early December 1915 and prepared for its inital test hop on the 12th. What was different about this one, however, went beyond the smooth, fully cantilevered exterior and into the all-metal structure and use of the Junkers-devised, thick sectioned, high lift wing. Built purely as a research machine, the two seat 120hp Mercedes DM powered Junkers J. I could accommodate a flight test observer. Military interest in the J. I was quickened by its warlike potential and it was trialled against a Rumpler C I, a machine that was considered the best in its class. Compared with the C I, the Junkers machine was 7mph faster on the level, at 106mph and even faster in a shallow dive. However, being built of steel, the J. I was heavy and, hence, markedly inferior to the Rumpler biplane in terms of climbing performance, earning the nicknames ‘Tin Donkey’ and ‘Flying Urinal’.As with all of Junkers’ early machines dealt with here, the actual design work on the J. I was led by Otto Reuter. It must be noted that this J. I was the company’s designation, whereas the armoured sesquiplane J I was a later machine that carried the firm’s designation J.4. (Junkers)

Above About the same time as the Junkers J. I was making its debut, the Gotha WD-10 was nearing completion, ready to enter flight trials early in 1916. While not representing such a fundamental advance as the J. I, this Oskar Ursinus creation merits more than passing interest for the novel and clever fashion in which the designer minimised the deleterious effects such things as floats would otherwise have on the fighter’s overall performance. Thanks to its refined in-flight lines, brought about by the retractable floats, the WD-10, with its 150hp Benz Bz III had a top level speed of 124mph at sea level. At this speed, the German single seat naval fighter could outpace France’s finest, in the shape of the Spad VII, first flown in April 1916. Perhaps it was fortunate for the Allies that the WD-IO was destroyed during flight test. The images not only show the aerodynamically cleansing affect of the retractable floats, but also the extremely neat housing of engine and fuselage flanking radiators devised by the Ursinus design team (Cowin Collection)

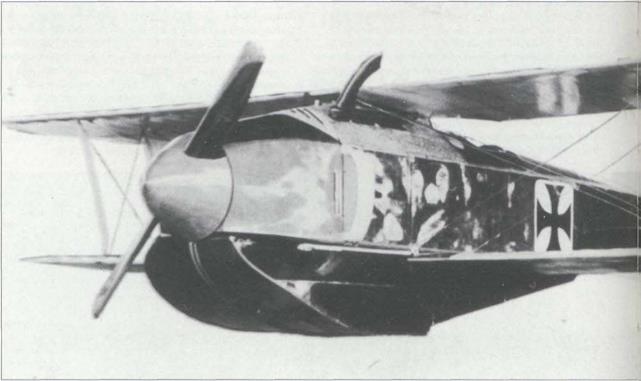

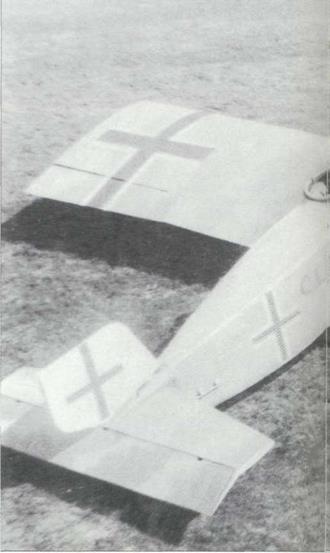

Right and top right The story of the initial, faltering evolution of the early Junkers metal monoplanes is an enthralling one and was outlined in the author’s monogram on the subject in Profile Publications No 187. Suffice it to say here that while Reuter and his team followed Hugo Junker’s concept to the letter, their notions of construction engineering owed more to bridge building than aviation practice. They showed a marked reluctance to switch from steel to light alloy, despite the fact that Zeppelin had been using it since 1908, or thereabouts. Perhaps the finest example of this is the Junkers J.7 experimental single seat fighter first flown in early September 1917. In its initial form, as photographed in flight, the machine was an

Right and top right The story of the initial, faltering evolution of the early Junkers metal monoplanes is an enthralling one and was outlined in the author’s monogram on the subject in Profile Publications No 187. Suffice it to say here that while Reuter and his team followed Hugo Junker’s concept to the letter, their notions of construction engineering owed more to bridge building than aviation practice. They showed a marked reluctance to switch from steel to light alloy, despite the fact that Zeppelin had been using it since 1908, or thereabouts. Perhaps the finest example of this is the Junkers J.7 experimental single seat fighter first flown in early September 1917. In its initial form, as photographed in flight, the machine was an

aerodynamic and fighter pilot’s nightmare, with a radiator towering above the engine, not only creating a huge drag, but totally obscuring forward pilot visibility. At this time, the J.7 also had swivelling wingtips in place of the standard ailerons. The ground-based image shows the same aircraft some 15 months later and looking almost indistinguishable from the prototype D I fighter, many of whose features had been evolved thanks to the J.7. (Junkers and Peter M. Grosz)

|

|

Although seemingly out of place in this section, the experimental Fokker V.26, precursor to the EV/D VIII, is included to show how Anthony Fokker was to benefit aerodynamically from the Junkers company’s faltering production engineering practices. During the summer of 1917, it was becoming clear that the much-needed, armoured Junkers J I was suffering a production engineering bottleneck. Under pressure from on

Although seemingly out of place in this section, the experimental Fokker V.26, precursor to the EV/D VIII, is included to show how Anthony Fokker was to benefit aerodynamically from the Junkers company’s faltering production engineering practices. During the summer of 1917, it was becoming clear that the much-needed, armoured Junkers J I was suffering a production engineering bottleneck. Under pressure from on

high, Hugo Junkers was forced to amalgamate his aircraft company with that of Fokker’s on 20 October 1917. As far as can be determined, Fokker’s periodic presence did nothing to unblock the bottleneck, but gave him unrestricted access to Junkers’ developmental results, including the thick-sectioned, high lift wing that Fokker incorporated into the V.26 and a number of his other prototypes. Incidentally, this image shows the V.26 with its tail up on a trestle which has not been retouched out of the picture, making the landing gear struts look overly complicated. (Cowin Collection)

Below and right Before and after images showing the prototype Junkers J.8 two seat close-support fighter and its production derivative, the Junkers Cl I. Work on the sole J.8 started in October 1917, aimed at providing a successor to the armoured Junkers J I. As it transpired, the J.8, with its 160hp Mercedes D III, had a top level speed of 116mph and impressed those that flew it at the first of the 1918 fighter trials. Not only did the J.8 lead directly to the Cl I production contract, but its development contributed greatly to solving many of the single seat J.7’s ongoing problems. Too late to have any effect in the air war, the 41 Junkers Cl Is completed stood up well, alongside their single seat Junkers D I when operated in the 1919 Baltic War. Powered by a 185hp Benz Bz IlIa, the Cl I had a top level speed of 118mph and a ceiling of 17,000 feet. Armament on later machines comprised two 7.92 Spandaus for the pilot, along with the flexibly-mounted 7.92mm Parabellum in the rear. (Junkers)

Below and right Before and after images showing the prototype Junkers J.8 two seat close-support fighter and its production derivative, the Junkers Cl I. Work on the sole J.8 started in October 1917, aimed at providing a successor to the armoured Junkers J I. As it transpired, the J.8, with its 160hp Mercedes D III, had a top level speed of 116mph and impressed those that flew it at the first of the 1918 fighter trials. Not only did the J.8 lead directly to the Cl I production contract, but its development contributed greatly to solving many of the single seat J.7’s ongoing problems. Too late to have any effect in the air war, the 41 Junkers Cl Is completed stood up well, alongside their single seat Junkers D I when operated in the 1919 Baltic War. Powered by a 185hp Benz Bz IlIa, the Cl I had a top level speed of 118mph and a ceiling of 17,000 feet. Armament on later machines comprised two 7.92 Spandaus for the pilot, along with the flexibly-mounted 7.92mm Parabellum in the rear. (Junkers)

|

|

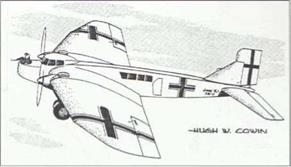

No resume of what Germany had up its sleeve in the way of bomber development would be complete without reference to the Adolf Rohrbach-designed Zeppelin-Staaken E 4250, dealt with on pages 26 and 27 of the first in this series of books, X – Planes. The other obvious candidate for analysis is the long range Junkers R I, seen here. By October 1916, the German Army Air Service was very aware that it had no heavy bombers capable of carrying out daylight raids and sought industry proposals to remedy matters. Junkers put work underway on their R I in January 1917, the design being finalised in March of that year. What Junkers were proposing was a fully cantilevered monoplane with a 5-man crew and powered by four unspecified engines housed transversely within the thick wing’s inboard sections. These paired engines supplied power through a combining gearbox to drive the bomber’s two propellers. Performance estimates for the R I included a top level speed of 112mph, an operational ceiling of 17,060 feet and a maximum bomb load of 3,305lbs. Where the R I really came into its own was over its ability to carry a 2,200lb load of bombs over a

radius of action of 380 miles. With wind tunnel testing complete and work underway on R 57/17, the first of the two machines ordered, the R I would have given the Allies pause for thought had it gone into service, particularly as even the first generation of lumbering biplane R-planes had proved exceptionally difficult to combat in operational service. (Hugh W Cowin)

|

|

The first of a small number of pre-production Junkers D I single seat fighters was completed at the end of April 1918.The short fuselage seen on this aircraft was replaced by a longer one on the 41 production D Is. Powered by a 185hp BMW IlIa, the production examples had a top level speed of 145mph,

along with an operational ceiling of 19,700 feet. The interesting thing about the image of a D I after it had suffered a nose-over accident at speed, following a landing gear collapse, is the comparatively light damage sustained. This and other D Is used for service evaluation in the last weeks of the war flew with a non-standard natural metal finish. (Cowin Collection)

|

РЯИМИРИН |