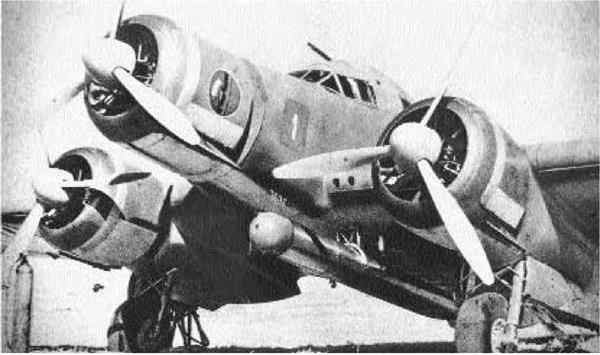

Type: Medium Bomber; Transport

Dimensions: wingspan, 78 feet, 8 inches; length, 58 feet, 4 inches; height, 14 feet, 7 inches Weights: empty, 13,890 pounds; gross, 23,040 pounds Power plant: 3 x 700-horsepower Piaggio P. X radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 211 miles per hour; ceiling, 26,240 feet; range, 1,336 miles Armament: up to 6 x 7.7mm machine guns; 2,205 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1935-1944

he handsome SM 81 was among the world’s best bombers when it first appeared. Despite growing obsolescence, they appeared wherever Italian troops fought in World War II.

In 1934 the appearance of the successful SM 73 commercial transport led to its development for military purposes. The prototype SM 81 emerged the following year with very similar lines. It was a large, low-wing monoplane in trimotor configuration, and in the course of a very long career a variety of differing engines was mounted. The craft was made of metal framework throughout, covered in fabric, and possessed two large, spatted landing gear. Although intended as a dedicated bomber, its roomy fuselage could also accommodate up to 18 fully equipped troops. SM 81s were rushed into service during the invasion of Ethiopia, where they rendered good service in bomber, transport, and reconnaissance roles. It thereafter served as the standard Italian bomber type until the appearance of the much superior SM 79s in 1937. Mussolini so liked the easy-flying

craft that he adopted one as his personal transport, and flew it regularly.

The Pipistrello (Bat) enjoyed an active service career that ranged the entire Mediterranean. They were among the first Italian aircraft to assist Franco’s Spanish Nationalist forces in 1936, performing well against light opposition. In 1940, after Italy’s entrance into World War II, the aging craft flew missions wherever Italian forces deployed. They bombed British targets in East Africa up through 1941, but the lightly armed craft took heavy losses. Thereafter, it became necessary to employ SM 81s exclusively as night bombers throughout the North African campaign. They raided Alexandria on numerous occasions but were subsequently employed in transport and other second-line duties. In 1942 alone, the 18 Stormo Traspori (transport squadron) made 4,105 flights, conveying 28,613 troops and 4.5 million pounds of supplies. A handful of SM 81s survived up to the 1943 Italian surrender, and they found service with both sides until war’s end. Production amounted to 534 machines.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber; Trainer

Dimensions: wingspan, 28 feet, 6 inches; length, 57 feet, 6 inches; height, 16 feet Weights: empty, 15,432 pounds; gross, 34,612 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 5,115-pound thrust Rolls-Royce Turbomeca Adour Mk 102 turbofan engines Performance: maximums peed, 1,056 mile per hour; ceiling, 45,930 feet; range, 530 miles Armament: 2 x 30mm cannons; up to 10,000 pounds of bombs and rockets Service dates: 1972-

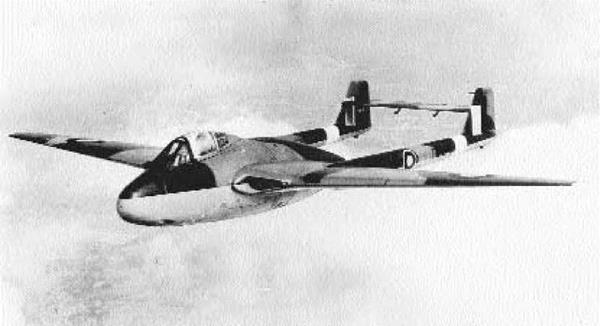

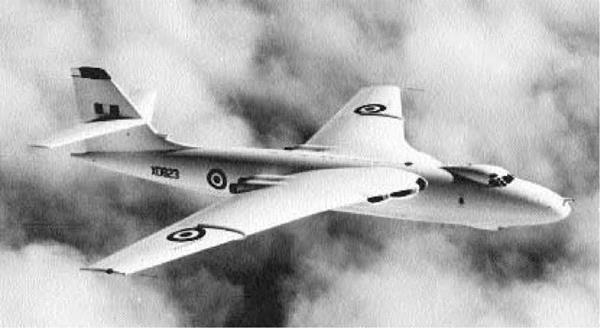

he highly capable Jaguar is one of the most successful multinational aircraft designs. Although originally designed as a trainer, it has since matured into a potent strike fighter.

By 1965 the great expense of modern military aircraft induced France and Great Britain to enter a joint program for developing an advanced jet trainer that could also double as a ground-attack craft. At length British Aircraft Corporation (now British Aerospace, or BAe) and Breguet (now Dassault) were tasked with designing such machines on a cost – effective basis. A basic prerequisite was the ability to deliver heavy ordnance at low level, high speed, and considerable range with great accuracy. The Jaguar prototype emerged in September 1968 as a high-wing jet with a sharply streamlined profile and highly swept wings. It featured tall landing gear to facilitate ease of loading large weapons on the numerous wing hardpoints. Being powered by two high-thrust Adour turbofan engines ensured that the craft possessed good STOL (short takeoff and landing) capabilities,

even when fully loaded. The first version, the Jaguar A, was a single-seat strike fighter deployed in France in 1972. This was followed by the Jaguar E, an advanced two-seat trainer. Britain, meanwhile, received deliveries of the single-seat Jaguar GR Mk 1 and the dual-seat Jaguar B trainer. Total production of European variants reached 400 machines. Both France and Britain have also operated them abroad, during the 1991 Gulf War, in Chad, and in Mauritania. The Jaguars are currently being phased out by the more advanced Panavia Tornado, but they maintain their reputation as excellent aircraft.

The good performance and easy maintenance of the Jaguar made them ideal for the overseas market, so an export version, the Jaguar International, was created. This variant was based upon the British GR 1 and could be fitted with advanced Agave radar and Sea Eagle antiship missiles. Thus far, India has proven the biggest customer, although small orders have also been placed by Ecuador, Nigeria, and Oman.

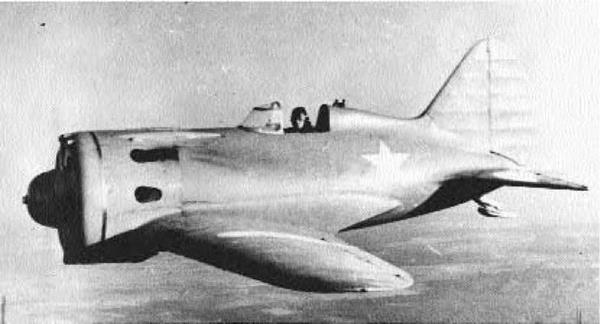

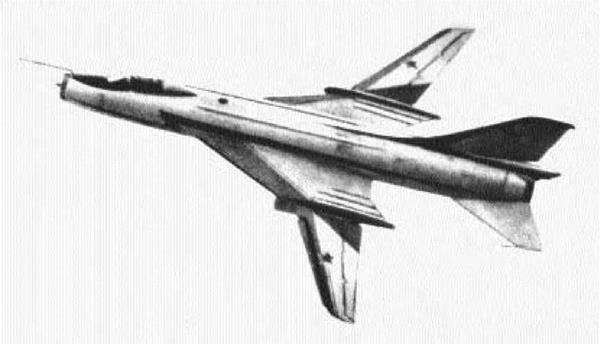

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 30 feet, 2 inches; length, 48 feet, 11 inches; height, 12 feet, 9 inches

Weights: empty, 12,700 pounds; gross, 22,045 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 5,730-pound thrust Liming Wopen R-9BF turbojets

Performance: maximum speed, 900 miles per hour; ceiling, 58,725 feet; range, 370 miles

Armament: 2 x 30mm cannons; up to 1,100 pounds of bomb or rockets

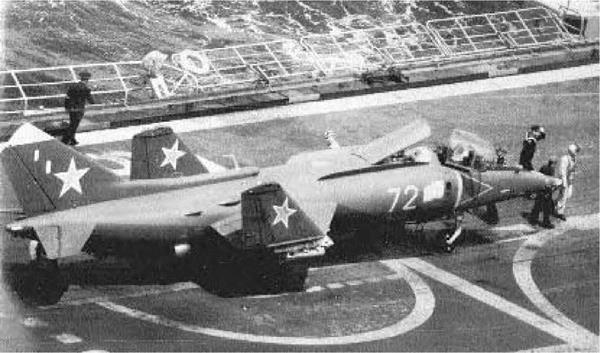

Service dates: 1958-

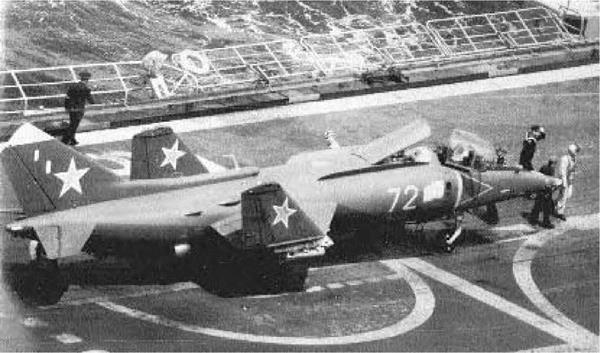

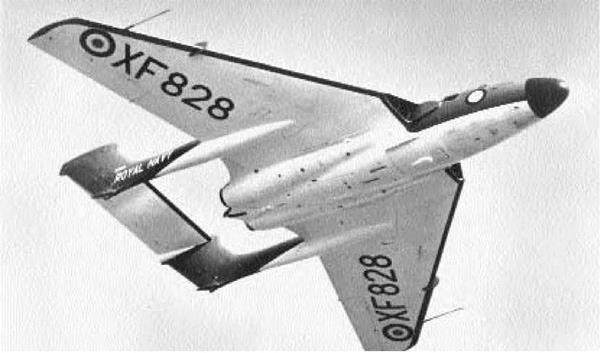

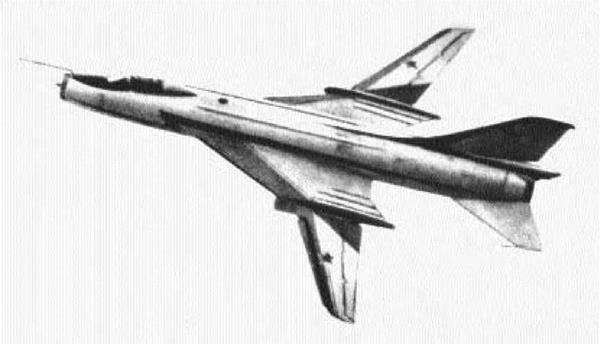

he J 6 remains the single-most important aircraft in China’s arsenal. Continually improved since its inception, it remains a formidable dogfighter.

The Russian MiG 19 interceptor first flew in 1953 and subsequently became one of the world’s earliest mass-produced supersonic fighters. It was acquired in great quantities by the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact before being supplanted by more modern MiG 21s in 1960. Two years previously, China contemplated construction of the MiG 19 under license. The craft was rugged, endowed with high performance, and exhibited excellent powers of maneuverability and climb. In 1958 the Shenyang Factory at Mukden obtained blueprints to the craft and manufactured its first example as the J 6. A handful of the craft had been turned out by the advent of the Cultural Revolution in 1961, which virtually gutted the Chinese aviation industry. Mass production could not resume until 1973; close to 3,000 have since been built. Like its Russian counterpart, the J 6 is a rakish all-metal jet with midmounted, highly

swept wings and tail surfaces. For added stability, the wings display pronounced fences across the chord. J 6s have since been fitted with a succession of more powerful engines and maintain a high-performance profile. To date it still fulfills numerous fighter, ground-attack, and reconnaissance missions within the People’s Liberation Air Force.

To improve its leverage with Third World nations, many of them desperately poor, China cultivated their friendship by offering the J 6 for export. Ready client states include Albania, Bangladesh, Egypt, and North Korea. But the most notable customer in this instance is Pakistan, which continues operating several squadrons of constantly refurbished J 6s. In combat with more advanced Indian aircraft, the redoubtable warhorse has unequivocally held its own, despite being based on obsolete technology. The J 6 and its export models will undoubtedly see continued use well into the twenty – first century. They have since received the NATO designation FARMER.

|

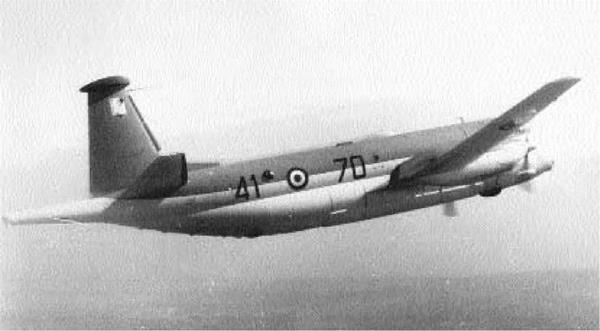

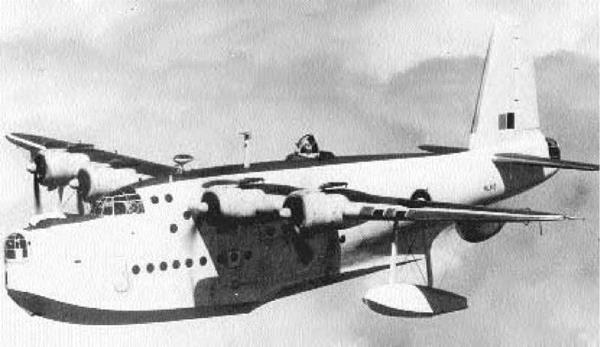

Type: Antisubmarine; Patrol-Bomber; Air/Sea Rescue

|

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 108 feet, 9 inches; length, 109 feet, 9 inches; height, 32 feet, 8 inches Weights: empty, 51,367 pounds; gross, 99,200 pounds

Power plant: 5 x 3,493-horsepower General Electric T46 turboprop engines Performance: maximum speed, 318 miles per hour; ceiling, 23,600 feet; range, 2,372 miles Armament: none Service dates: 1968-

he US 1 is the most advanced and capable flying boat ever built. Using sophisticated air boundary control technology, it can take off and land in amazingly short distances.

Japan is preponderantly a maritime nation, its destiny closely linked to control of the seas surrounding it. For this reason flying boats have always been something of a specialty in Japan’s history, and during World War II it produced some of the finest machines of that conflict. By 1965 the Japan Maritime Defense Force sought modern replacements for its Korean War-vintage Grumman UF-2 Albatroses. This was being sought for improved search-and-rescue capability, as well as antisubmarine warfare (ASW). They approached ShinMaywa (previously Shin Meiwa and, before that, Kawanishi) to develop such a machine. A team headed by Dr. Shizuo Kikuhara, who was responsible for the superb H8K Emily of World War II, responded with a large and modern four-engine craft. The PS 1 was a high-wing, all-metal monoplane with a

single-step hull and a high “T” tail. The aircraft also employed a fifth engine driving a unique air boundary control device. This vents engine gases and blows them directly against the lowered flaps, providing extra lift for takeoffs and landings. Such technology allowed the big craft to operate from relatively short distances. The hull also permits working in waves as high as 10 feet. ShinMaywa ultimately constructed 23 PS 1s, all of which were retired from ASW service in

1989.

In 1974 ShinMaywa tested the first prototype US 1, a dedicated search-and-rescue amphibian. It is outwardly identical to the earlier PS 1 save for the presence of retractable landing gear in the hull. The new craft has been stripped of all submarine detection equipment to make room for up to 36 stretchers. A maximum of 100 persons could be carried in emergency situations. A total of 13 have been acquired thus far, and a new version, the US 1kai, with improved Allison turboprop engines, is under evaluation.

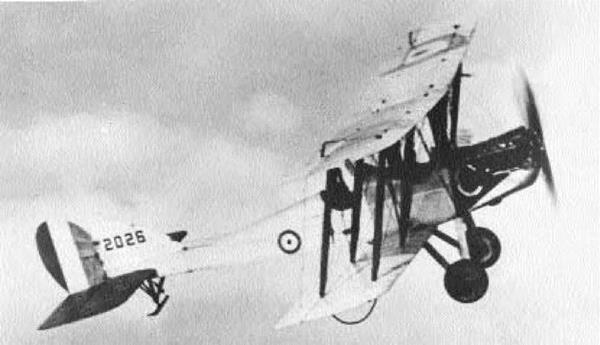

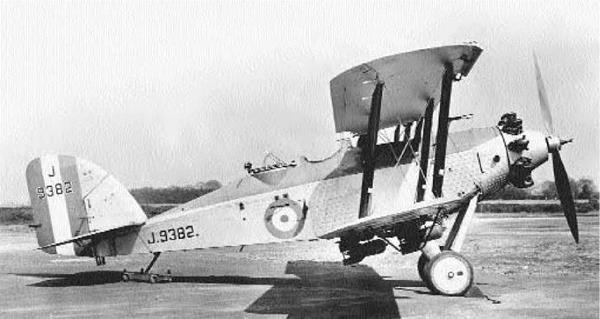

Type: Torpedo-Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 63 feet, 6 inches; length, 40 feet, 7 inches; height, 13 feet, 6 inches

Weights: empty, 3,703 pounds; gross, 5,363 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 225-horsepower Sunbeam liquid-cooled in-line engine

Performance: maximum speed, 88 miles per hour; ceiling, 9,000 feet; range, 150 miles

Armament: 1 x.303-inch machine gun; 1 x 14-inch torpedo

Service dates: 1915-1918

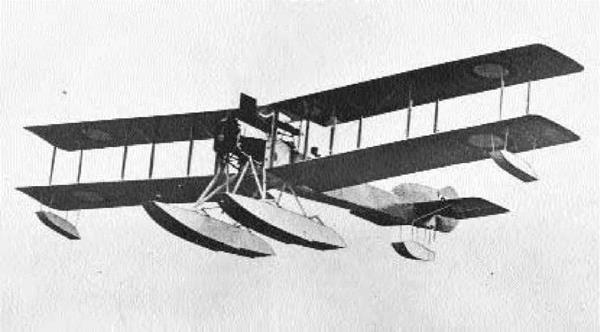

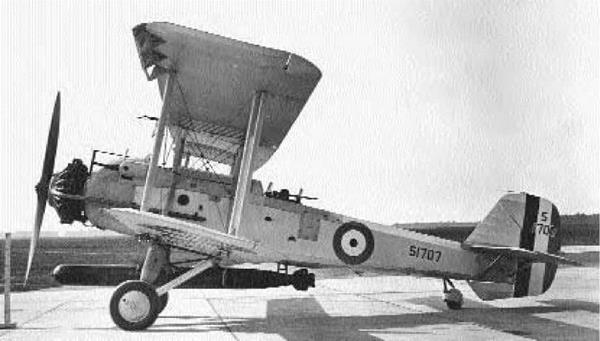

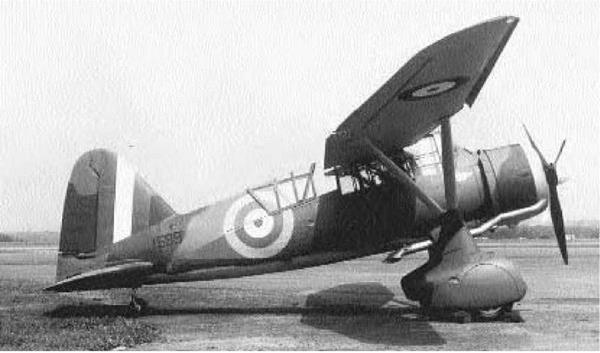

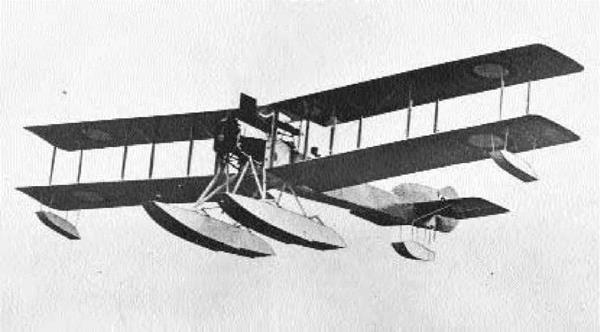

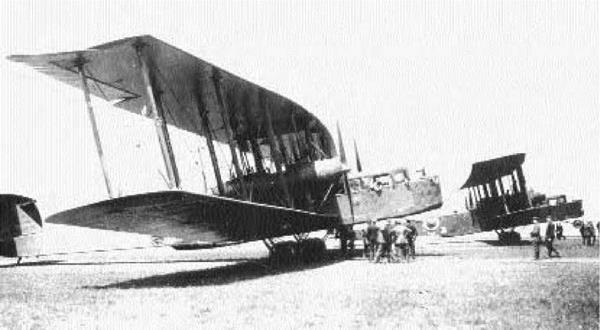

he lumbering Short 184 was an illustrious veteran of World War I with an impressive combat record. It was actively engaged in the Battle of Jutland and also launched the first aerial torpedo attack against enemy vessels.

The Short 184 had its origins in the beliefs of Commodore Murray F. Sueter, who in 1914 convinced the British Admiralty to develop an airplane capable of dropping torpedoes. This was then a revolutionary new concept. Accordingly, the Short 184 prototype flew the following year, so designated by the Admiralty practice of naming aircraft types by numbers assigned to the first example. The Short 184 was a standard, three-bay biplane of wood-and – fabric construction. The wings were extremely long, with the top ones sporting ailerons and the lower ones tipfloats. The fuselage was also somewhat attenuated and mounted two pontoon-type floats. Despite its somewhat fragile appearance, the craft handled well and could hoist a heavy torpedo aloft. A total of 650 were acquired.

The Short 184 made aviation history while attached to the floatplane tender HMS Ben-my-Chree during the Dardanelles campaign. On August 12, 1915, a Short 184 torpedoed and severely damaged a Turkish steamer. This success was repeated five days later when a steam tug was sent to the bottom, again demonstrating the validity of Sueter’s theories. During the next three years, these creaking floatplanes distinguished themselves in a variety of missions and climes. Throughout the spring of 1916, five Short 184s operated from the Tigris River at Ora, Iraq, dropping supplies to the beleaguered garrison at Kut-al-Imara. On May 31, 1916, a Short 184 conducted history’s first naval reconnaissance flight when it espied part of the German battle fleet and successfully relayed coordinates. The ubiquitous Short 184 flew from every conceivable British naval base, be it in England, the Mediterranean, the Aegean, the Red Sea, Mesopotamia, or the French coast. They retired from British service after the war, but several examples were operated by Greece and Estonia as late as 1933.

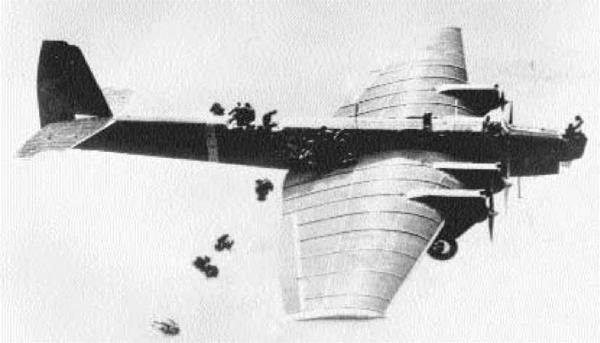

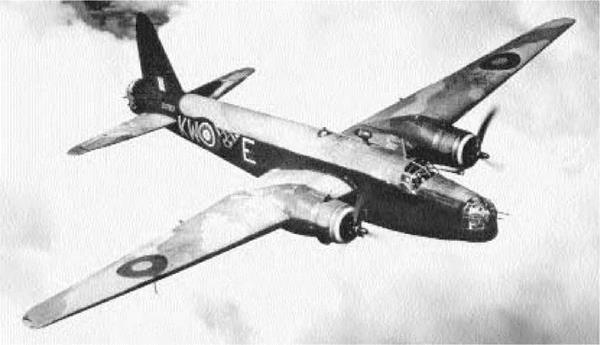

Type: Heavy Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 99 feet, 1 inch; length, 87 feet, 3 inches; height, 22 feet, 9 inches

Weights: empty, 43,200 pounds; gross, 70,000 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 1,650-horsepower Bristol Hercules XVI radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 270 miles per hour; ceiling, 17,000 feet; range, 2,010 miles

Armament: 8 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 14,000 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1941-1945

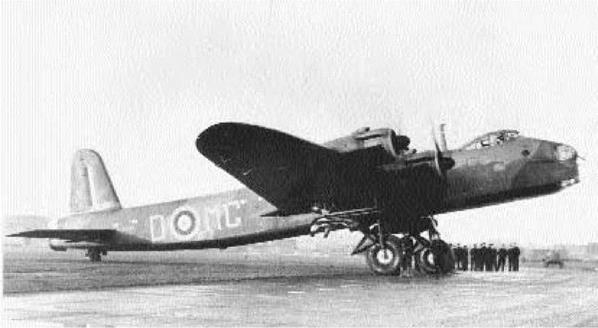

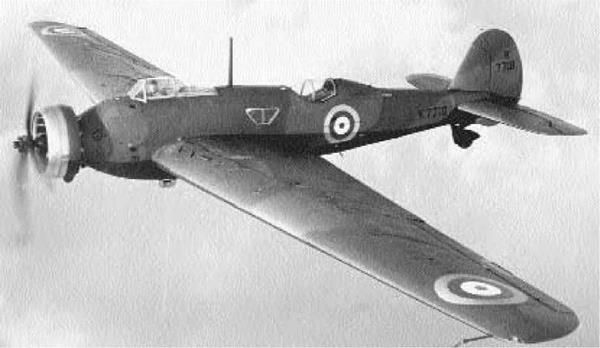

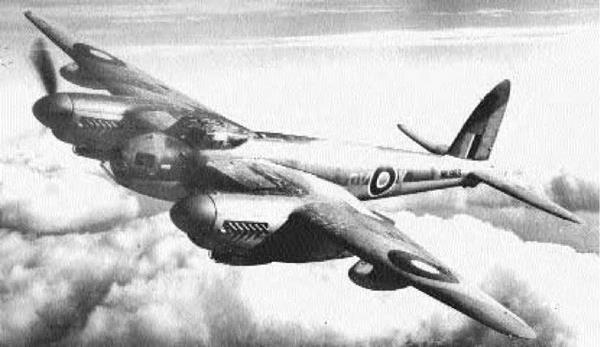

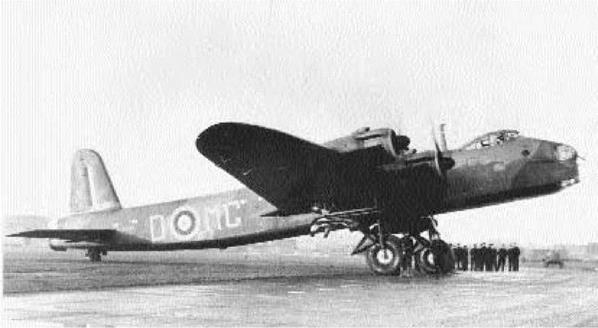

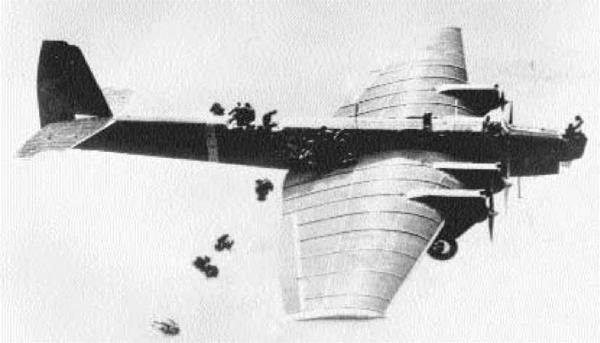

he slab-sided Stirling was Britain’s first strategic bomber and the first to achieve operational status during World War II. Visually impressive, it suffered from poor altitude performance and was eventually eclipsed by the Avro Lancaster and Handley Page Halifax.

In 1936 the British air staff sought acquisition of its first strategic bomber, so the Air Ministry issued Specification B.12/36 for a four-engine aircraft. Several prototypes were entered by different firms, but Short’s model proved the most successful. It was a large, high-wing monoplane with smooth, stressed skin. The fuselage was rather long, was slab-sided, and housed three power turrets for defense. Because the wing was so far off the ground, enormous landing gear were required, causing the aircraft to appear larger than it actually was. A potential problem was the wingspan. Because ministry specifications mandated that the new craft should fit into existing hangars, its wings could not exceed 100 feet. Thus, the Stirling, which was rather large, always suffered from insufficient lift.

Nonetheless, the decision was made to acquire the bomber in 1939, and within two years the first squadrons were outfitted.

In service the Stirling enjoyed a rather mixed record. The big craft was structurally sound and, at low altitude, quite maneuverable for its size. However, its short wing enabled it to reach barely 17,000 feet while fully loaded—an easy target for antiaircraft batteries and enemy fighters. Another unforeseen shortcoming was the bomb bay, which was constructed in sections and could not accommodate ordnance larger than 2,000 pounds—the largest weapon available in 1938. Thus, unlike the Hali- faxes and Lancasters that followed, its utility as a strategic weapon was decidedly limited. Stirlings nonetheless performed good service with RAF Bomber Command until 1944, when they were relegated to secondary tasks. Foremost among these was glider-towing, which they extensively performed at Normandy in June 1944. By 1945 Stirlings had flown 18,446 sorties and dropped 27,281 tons of bombs. A total of 2,373 were constructed.

|

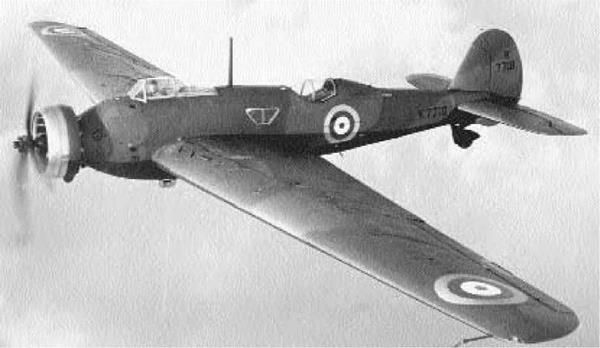

Type: Patrol-Bomber

|

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 112 feet, 9 inches; length, 85 feet, 3 inches; height, 32 feet, 10 inches Weights: empty, 37,000 pounds; gross, 65,000 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 1,200-horsepower Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp radial engines Performance: maximum speed, 213 miles per hour; ceiling, 17,900 feet; range, 2,980 miles Armament: 10 x.303-inch machine guns; 2,000 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1938-1959

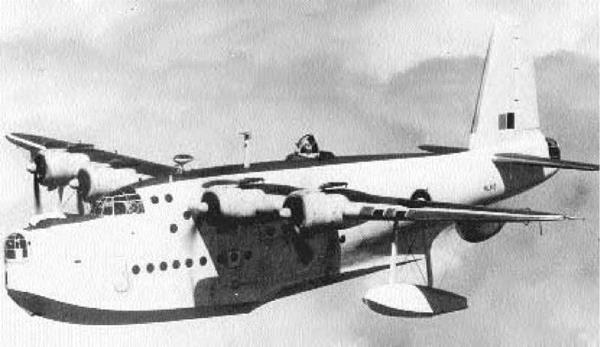

he large, graceful Sunderland was among World War Il’s best flying boats. Because it bristled with armament, the Germans regarded it as the “Flying Porcupine.”

The advent of successful Short Empire C-class flying boats in 1933 persuaded the British Air Ministry to consider its adoption for military purposes. That year it issued Specification R.2/33 to replace the aging biplane flying boats with a new monoplane craft. The prototype Sunderland was heavily based upon the civilian craft when it first flew in 1937. It was a high-wing, four-engine airplane with stressed- skin construction and a very deep, two-step hull. The spacious hull of the Sunderland allowed for creature comforts not associated with military craft. These included comfortable bunks, wardrooms, and a galley serving hot food, all of which mitigated the effects of 10-hour patrols. The craft was also the first flying boat fitted with powered gun turrets in the nose, dorsal, and tail positions, as well as the first to carry antishipping radar. Despite its bulk, the

Sunderland handled well in both air and water and became operational in 1938. World War II commenced the following year, and Sunderlands ultimately equipped 17 Royal Air Force squadrons.

This capable aircraft played a vital role in the ongoing battles in the Atlantic. They cruised thousands of miles over open ocean, providing convoy escorts and attacking U-boats whenever possible. The first submarine kill happened in January 1940 when a Sunderland forced the scuttling of U-55. The big craft, by flying low to the water, could also defend itself handily. On several occasions, Sunder – lands beat off roving bands of Junkers Ju 88s with considerable loss to the attackers. The Germans held the big craft in such esteem that they nicknamed it the Stachelschwein (Porcupine). Sunder – lands performed useful service in the Atlantic and Pacific theaters throughout the war. They were retained in frontline service until 1959, giving them— at 21 years—the longest service record of any British combat type. A total of 721 were built.

|

Type: Fighter

|

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 27 feet, 4 inches; length, 18 feet, 8 inches; height, 8 feet, 11 inches

Weights: empty, 1,190 pounds; gross, 1,620 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 160-horsepower Siemens-Halske rotary engine

Performance: maximum speed, 118 miles per hour; ceiling, 26,240 feet; range, 250 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns Service dates: 1918-1919

he barrel-chested Siemens-Schuckert D III and D IV were among the finest fighters developed during World War I. At high altitude they possessed superior performance to the legendary Fokker D VII.

Since 1916 the famous Siemens-Schuckert Werke firm had been experimenting with numerous rotary-engine fighter designs. Eventually the program came under the sway of designer Harald Wolf, who originated a unique aircraft suitable for the large Siemens-Halske Sh III rotary engine. Called the D III, it was a squat, barrel-chested machine possessing rather sleek lines. It had two-bay wings of conventional wooden construction, with the upper wing of considerably lower chord than the lower one. The massive engine was completely enclosed by a close-fitting cowling and drove a four-blade propeller. To counteract strong torque forces, the right wing was actually four inches longer than the left. In sum, this was a compact, powerful design of unusual military promise.

In the winter of 1917 small batches of D IIIs arrived at the front for evaluation under combat

conditions. Pilots were awed by its aerial agility and phenomenal climb. In level flight, however, it was somewhat slower than other fighters, and the SH III engine was prone to overheating. Engine seizures were frequent, and by February 1918 all 20 D IIIs returned to the factory for modifications. They reappeared at the front by summer, along with 60 production models, having the lower part of their cowling cut off to facilitate cooling.

Concurrently, an improved version, the D IV, was also under development. Outwardly this model appeared identical to the D III, but it possessed a redesigned top wing and a large spinner with cooling louvers. These modifications endowed the D IV with greater speed and even faster climb. By the fall of 1918 a total of 118 had been constructed, which equipped four squadrons. In service the D IVs proved the only German fighter capable of tackling the formidable Sopwith Camels and Snipes on equal terms. In 1919 several examples were flown by German against Bolshevik forces in the Baltic.

Type: Heavy Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 97 feet, 9 inches; length, 56 feet, 1 inch; height, 15 feet, 6 inches

Weights: empty, 8,378 pounds; gross, 12,125 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 150-horsepower Sunbeam liquid-cooled in-line engines

Performance: maximum speed, 85 miles per hour; ceiling, 10,500 feet; range, 435 miles

Armament: 7 x 7.7mm machine guns; 2,200 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1914-1924

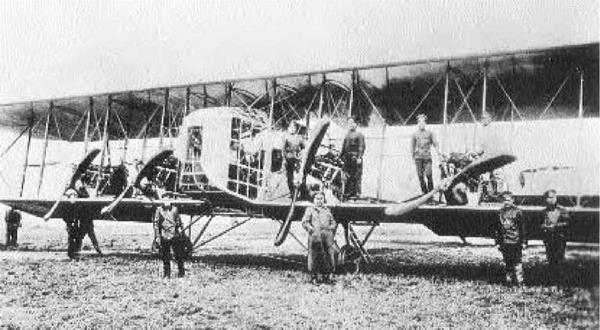

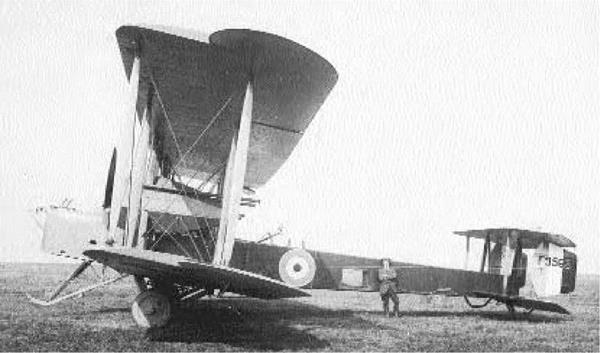

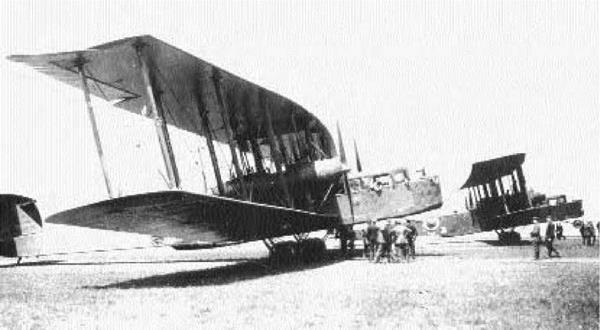

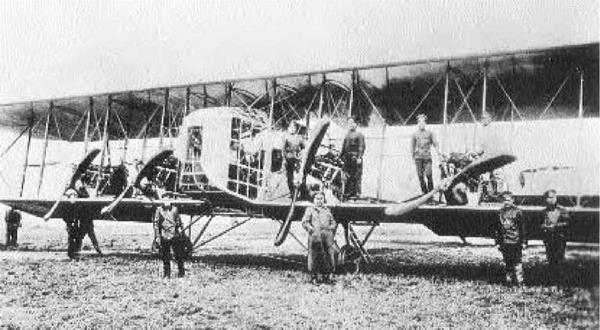

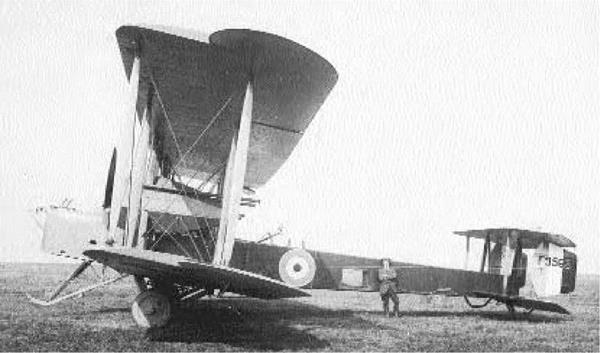

he massive Ilya Muromets was the world’s first four-engine bomber—and a good one at that. In three years it dropped 2,200 tons of bombs on German positions, losing only one plane in combat.

In 1913 the Russo-Baltic Wagon Works constructed the world’s first four-engine aircraft under the direction of Igor Sikorsky. Dubbed the Russki Vi – tiaz (Russian Knight), it was also the first to mount a fully enclosed cabin. This giant craft safely completed 54 flights before being destroyed in a ground accident. In 1914 Sikorsky followed up his success by devising the first-ever four-engine bomber and christened it Ilya Muromets after a legendary medieval knight. The new machine possessed straight, unstaggered, four-bay wings with ailerons only on the upper. The fuselage was long and thin, with a completely enclosed cabin housing a crew of five. On February 12, 1914, with Sikorsky himself at the controls, the Ilya Muromets reached an altitude of 6,560 feet and loitered five hours while carrying 16 passengers and a dog! This performance, unmatched any

where in the world, aroused the military’s interest, and it bought 10 copies as the Model IM.

After World War I commenced in 1914, Sikorsky went on to construct roughly 80 more of the giant craft, which were pooled into an elite formation known as the Vozdushnykh Korablei (Flying Ships) Squadron. On February 15, 1915, they commenced a concerted, two-year bombardment campaign against targets along the eastern fringes of Germany and Austria. The Ilya Muromets carried particularly heavy loads for their day, with bombs weighing in excess of 920 pounds. This sounds even more impressive considering that ordnance dropped along the Western Front was usually hurled by hand! The mighty Russian giants were also well-built and heavily armed. In 422 sorties, only one was lost in combat, and only after downing three German fighters. Operations ceased after the Russian Revolution of 1917, with many bombers being destroyed on the ground. A handful of survivors served the Red Air Force as trainers until 1922.

|

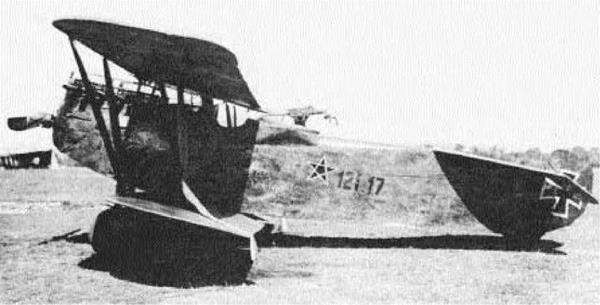

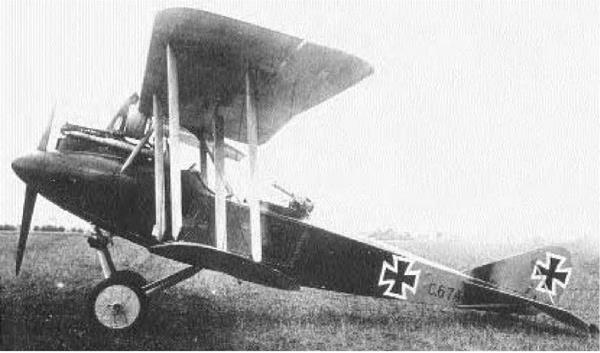

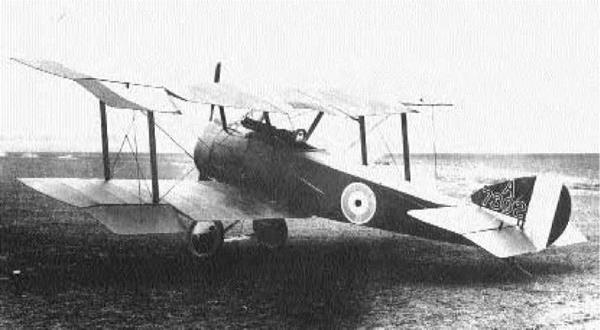

Type: Fighter; Reconnaissance

|

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 27 feet, 6 inches; length, 20 feet, 4 inches; height, 9 feet, 1 inch

Weights: empty, 897 pounds; gross, 1,490 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 80-horsepower Gnome air-cooled rotary engine

Performance: maximum speed, 73 miles per hour; ceiling, 11,482 feet; range, 200 miles

Armament: up to 2 x 7.62mm machine guns

Service dates: 1916-1924

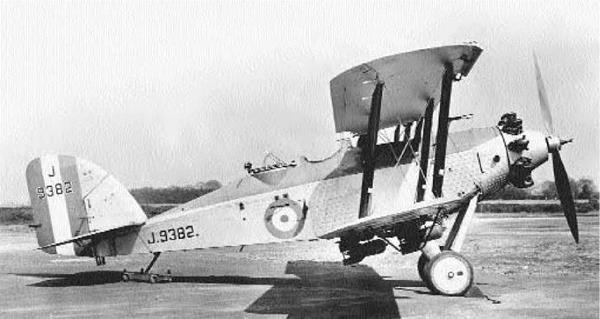

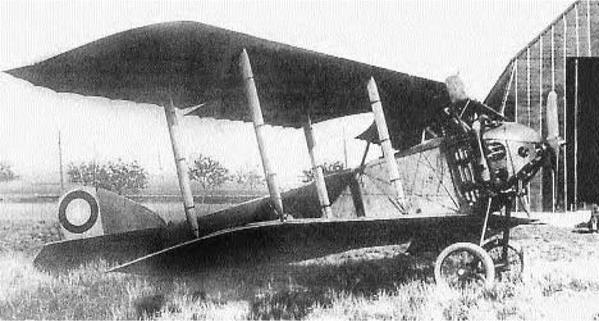

he diminutive S 16 was one of the earliest fighters to mount forward-firing interrupter gear. A mediocre craft, its robust construction permitted useful service under very harsh operating conditions.

The Russo-Baltic Wagon Factory had gained considerable renown through the efforts of its chief engineer, Igor I. Sikorsky. His four-engine Ilya Muromets bombers were among the most advanced in the world, and in the spring of 1914 he was instructed to design an escort fighter to assist the giant craft. The prototype emerged in February 1915 as the S 16. This was a small machine of conventional appearance and construction. It possessed a wire-braced wooden fuselage and a spacious cockpit for two crewmen. The single bay wings were affixed to the fuselage by dual struts, and the craft was built entirely of wood and canvas covering. The S 16 was originally designed to be powered by a 100- horsepower Gnome Monosoupape rotary engine, but shortages necessitated using a smaller, 80-horsepower version. Consequently, the S 16, which pos

sessed excellent flying characteristics, remained slow and underpowered. However, it was unique in mounting robust, four-wheeled landing gear. These allowed operations from the plowed fields that Russian forces utilized as airstrips. In winter, the S 16 could also be fitted with skis.

The S 16 was only marginally successful, but it is notable in being among the first Allied aircraft to utilize Russian-designed interrupter gear for machine guns to fire through the propeller arc. This system, conceived by naval Lieutenant G. I. Lavrov, was somewhat faulty (as were most early systems) and was usually complemented by a second, wing – mounted gun firing over the propeller. Only 34 S 16s were built by 1917, but they saw widespread service as reconnaissance craft. They were also deemed unsatisfactory for escorting the giant Ilya Muromets bombers, which proved very capable at defending themselves. After the Russian Revolution, the surviving S 16s were impressed into the Red Air Force as trainers. They dutifully served until being retired in 1924.

|

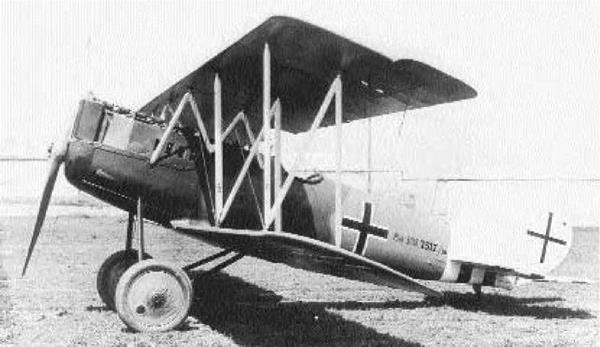

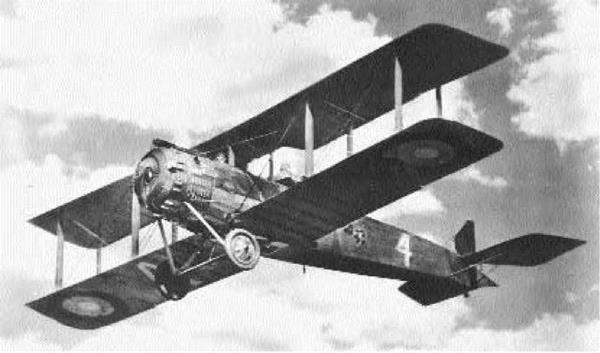

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber; Reconnaissance

|

|

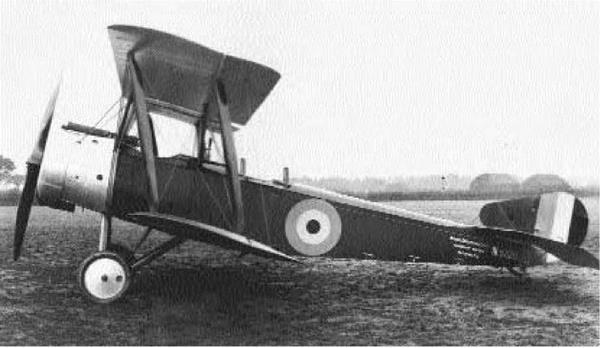

Dimensions: wingspan, 33 feet, 6 inches; length, 25 feet, 3 inches; height, 10 feet, 3 inches Weights: empty, 1,259 pounds; gross, 2,150 pounds Power plant: 1 x 130-horsepower Clerget rotary engine

Performance: maximum speed, 106 miles per hour; ceiling, 15,000 feet; range, 400 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 230 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1916-1918

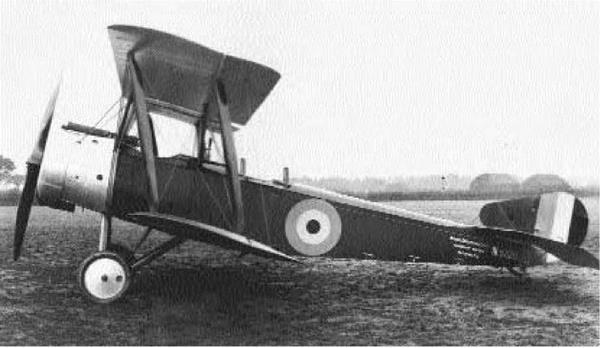

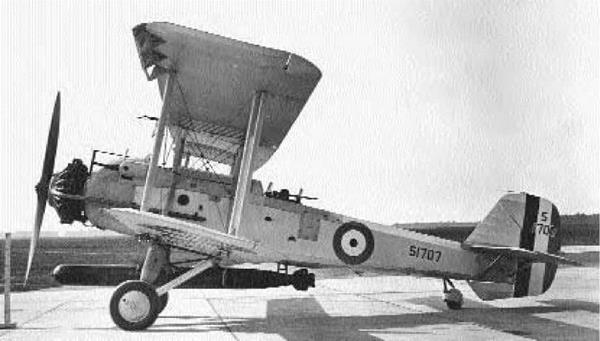

opwith 1 1/2 Strutters sported several technical innovations for their time and were exceptionally fine-looking aircraft. They compiled an exemplary combat service record in World War I as fighters, bombers, and scouts.

In 1915 the British Admiralty issued new specifications for a two-seat fighter, the first British tractor- type equipped with a synchronized machine gun for firing through the propeller arc. Sopwith completed the prototype in December of that year as a handsome, two-bay biplane powered by a rotary engine. In fact, the new craft sported two interesting innovations. The first was a form of air brake, consisting of two square sections on the lower wing that were hinged and could be lowered upon landing. The second was a variable-incidence tailplane that allowed the craft to be trimmed in flight. Like all Sopwith machines, the new Type 9400 was delightful to fly, responsive, and maneuverable. It was also heavily armed for its day, mounting both a forward-firing machine gun for the pilot and a ring-mounted weapon for the observer. Production began the following

spring; the first units reached the front in April 1916. Crews immediately dubbed it the 1 1/2 Strutter on account of the “W”-shaped inboard struts.

Strutters were operated by both Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service units and acquired a jack-of-all-trades reputation. They initially functioned as escort fighters and enjoyed considerable success, for very few two-seat aircraft were armed with interrupter gear. By that fall the newly arrived Albatros D I and Halberstadt fighters terminated this role, for the craft was too stable for violent defensive maneuvers. Fortunately, their versatility made them excellent bombing platforms, and several hundred single-seat versions were deployed by both services. The British ultimately constructed 1,513 Strutters, but its biggest customer was France, which manufactured an additional 4,500 machines. They were also employed by the American Expeditionary Force, which purchased 514 machines to serve as trainers in 1918. Strutters continued to function in various capacities until supplanted by more advanced types in 1918.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 28 feet; length, 18 feet, 9 inches; height, 8 feet, 6 inches Weights: empty, 929 pounds; gross, 1,453 pounds Power plant: 1 x 140-horsepower Clerget rotary engine

Performance: maximum speed, 113 miles per hour; ceiling, 19,000 feet; range, 200 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns Service dates: 1917-1919

he immortal Camel was the finest British fighter of World War I. A snubbed-nosed dervish, it helped wrest air superiority away from Germany and counted among its victims the legendary Manfred von Richthofen (the Red Baron).

Development of a new fighter to succeed the Sopwith Pup commenced in 1916 when Herbert Smith conceived a machine capable of greater maneuverability. He accomplished this by placing the heaviest parts—the engine, armament, and pilot— all within 8 feet of the nose section. This arrangement, coupled with the tremendous torque generated by a Clerget rotary engine, gave the ensuing Sopwith F1 fighter unparalleled turning ability. It was also the first British fighter designed to be equipped with twin Vickers machine guns firing through the propeller arc. These were closely enclosed in a distinctive hump that inspired the nickname Camel.

The Camel was unlike any British fighter to date and certainly differed from the Sopwith designs preceding it. Whereas the famous Pup and Triplane designs possessed gentle, almost sedate characteris

tics, the new machine was both unstable and unforgiving. These attributes rendered it a first-class fighter in the hands of an experienced pilot, for the Camel could outturn any German aircraft except the vaunted Fokker Dr I triplane. However, novice pilots found it a vicious handful and dangerous to fly, for careless turning inevitably led to fatal spins. Attrition among beginning pilots was appreciable high, but those who mastered the craft managed to shoot down an estimated 1,300 German airplanes, more than any other Allied fighter. Among the many victims was Baron von Richthofen himself, purportedly bagged by Captain Roy Brown of Naval Squadron No. 209 on April 21, 1918. A total of 5,490 Camels were built, including the 2 F1, a navalized version featuring shorter wings and a detachable fuselage for shipboard storage. Like its Royal Flying Corps counterparts, the navy Camels fought tenaciously, scored well, and even claimed the last Zeppelin shot down during the war. The mighty Sopwiths were all retired within months of the November 1918 Armistice and were replaced by an even finer machine, the Snipe. It remains a classic British warplane.

|

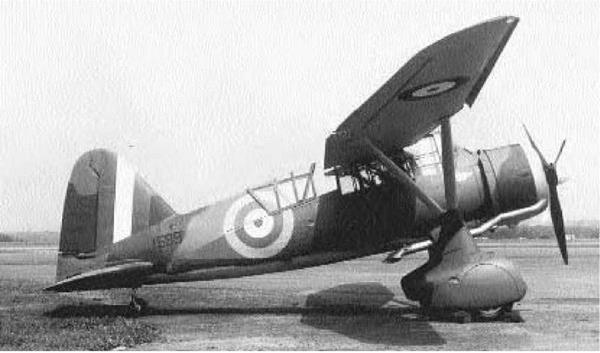

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber

|

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 32 feet, 6 inches; length, 22 feet, 3 inches; height, 8 feet, 6 inches Weights: empty, 1,391 pounds; gross, 2,008 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 200-horsepower Hispano-Suiza Vee liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 112 miles per hour; ceiling, 20,000 feet; range, 250 miles Armament: up to 4 x.303-inch machine guns; 100 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1918-1919

he ungainly Dolphin was the first multigun British fighter ever produced. It had fine high-altitude performance but, ironically, performed more useful work on the deck.

In 1917 Sopwith commenced work on a fighter that maximized vision and firepower at the expense of maneuverability. The new craft was an even bigger departure from traditional company norms in that it utilized an in-line, not rotary, engine. The prototype emerged in May 1917 and immediately raised eyebrows. The wings of equal length were set back in a negative stagger to afford the pilot greater frontal view. To that end, the top wing’s center section was also cut out and mounted low to the fuselage, allowing the pilot’s head to protrude. This afforded him a splendid field of vision but also guaranteed a broken neck—or worse—in the event of a noseover. The in-line motor gave the deep fuselage a rather pointed profile and mounted outboard radiators on either side. The armament was also worthy of note. In addition to two synchronized ma

chine guns in front, it possessed a pair of drum-fed Lewis machine guns mounted at an angle over the pilot’s enclosure. This craft, christened the 5F1 Dolphin, displayed excellent flying qualities, especially at high altitude, and the decision was made to enter production. Within a year 1,532 had been acquired.

Dolphins reached France in the spring of 1918 and were immediately viewed with suspicion. The geared Hispano-Suiza engine caused endless difficulties, and—owing to the wing arrangement—its stall characteristics caused many accidents. But pilots came to appreciate the fine high-altitude performance of the Dolphin and its robust construction. Curiously, many squadrons found the twin Lewis guns burdensome and discarded them altogether. Dolphins functioned as fighters for several months but found even greater success as ground-attack craft. Armed with four 25-pound bombs, they proved extremely effective at dispersing infantry formations. The novel Sopwiths served well until war’s end and were phased out of service the following year.

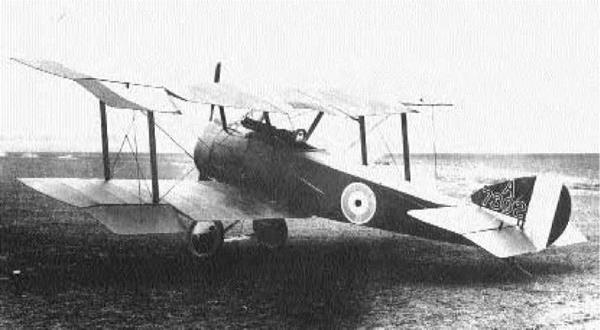

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 26 feet, 6 inches; length, 19 feet, 3 inches; height, 9 feet, 5 inches

Weights: empty, 790 pounds; gross, 1,225 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 80-horsepower Gnome Monosoupape rotary engine

Performance: maximum speed, 111 miles per hour; ceiling, 17,500 feet; range, 310 miles

Armament: 1 x.303-inch machine gun

Service dates: 1916-1917

hen first introduced, the elegant Pups were hailed as the most perfect flying machines of their day. They were also capable dogfighters and compiled an astonishing combat record.

In 1915 Sopwith’s Herbert Smith decided to produce a new fighter based on a personal aircraft owned by test pilot Harry Hawker. The resulting prototype looked like a scaled-down, single-seat version of the already capable 1 1/2 Strutter. It was a small, handsome craft driven by a rotary engine and constructed of wood and fabric. This new Model 9901 possessed broad wings of equal length, a reduced center section to improve pilot vision, and the same distinctive inboard struts as the 1 1/2 Strutter. This close visual association gave rise to the craft’s popular name—the “pup” of the previous airplane. Although distinctly underpowered, the Pup was in every respect a pilot’s machine. It was docile yet sensitive, and by virtue of very low wing loading it was able to maintain altitude during violent acrobatic maneuvering. The tidy craft equipped several

naval squadrons and arrived in France during the spring of 1916.

In combat, the pugnacious Pup became the terror of the Western Front. It tackled the feared Al – batros scouts with ease and outflew them at high altitude. The Royal Flying Corps was then hard – pressed owing to heavy casualties, and a number of Pup-equipped Royal Navy squadrons were dispatched to assist. The most famous of these, Naval Eight, flew for only three months and accounted for 20 enemy craft. Having themselves received the Pup, air corps units also asserted their superiority at great expense to the enemy. The diminutive plane gained further distinction by participating in landing experiments aboard the carrier HMS Furious. On August 2, 1917, a Pup flown by Commander F. J. Rutland became the first land plane to touch down on a moving ship at sea. By the fall of 1917, the splendid little Sopwiths were gradually withdrawn and replaced by the newer Camels and Royal Aircraft Factory SE 5s. A total of 1,770 had been manufactured.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 30 feet, 1 inch; length, 19 feet, 9 inches; height, 9 feet, 6 inches

Weights: empty, 1,312 pounds; gross, 2,020 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 230-horsepower Bentley BR 2 rotary engine

Performance: maximum speed, 121 miles per hour; ceiling, 20,000 feet; range, 300 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns Service dates: 1918-1926

ad World War I endured beyond the November 1918 Armistice, the Snipe might have gained renown as the best all-around fighter of the war. Accordingly, it served as the last rotary-engine airplane of the postwar period.

Throughout 1917 Herbert Smith worked on a more powerful successor to his already famous Camel. The new craft shared similar outlines with its predecessor but was built around the new 230- horsepower Bentley BR 2 rotary engine. Several prototypes were built, flown, and successively modified until rendered proficient. The 7F1 Snipe, as it was named, was a four-bay biplane design with a short fuselage and relatively long wings. Unlike the Camel, both wings were given several degrees of dihedral, and the top one had its center section reduced to improve pilot vision. The slab-sided fuselage of the former had also given way to a rounder, more streamlined form. And like its precursor, the Snipe possessed twin machine guns in a distinctive fairing over the engine, only now the hump was even more pronounced. Flight-testing concluded success

fully, and production commenced in the spring of 1918.

Only 200 Snipes had been completed by the time of the Armistice, equipping three squadrons. Nonetheless, the new fighter quickly gained repute as being quite possibly the best aircraft of its class during the war. It climbed better than the Camel, retained all the legendary maneuverability, and possessed none of the latter’s vicious spin characteristics. These traits were summarily displayed on October 27, 1918, when a Snipe flown by Canadian Major W. G. Barker single-handedly engaged 15 superb Fokker D VIIs, gaining him the Victoria Cross.

After the war, Snipes continued on as the first major Royal Air Force service fighter. Given their great aerial agility, they remained standard fare at aviation shows throughout the early 1920s, although their rotary-engine technology was approaching obsolescence. By 1926 the weary Snipes had been eclipsed by newer radial-engine fighters like the Gloster Grebe and the Armstrong-Whitworth Siskin. Production totaled 2,103 machines.

|

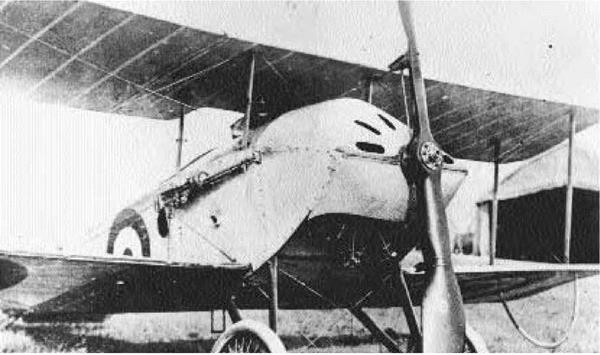

Type: Reconnaissance; Light Bomber

|

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 25 feet, 6 inches; length, 20 feet, 4 inches; height, 8 feet, 5 inches Weights: empty, 720 pounds; gross, 1,120 pounds Power plant: 1 x 80-horsepower Gnome rotary engine

Performance: maximum speed, 93 miles per hour; ceiling, 15,000 feet; range, 300 miles Armament: none Service dates: 1914-1915

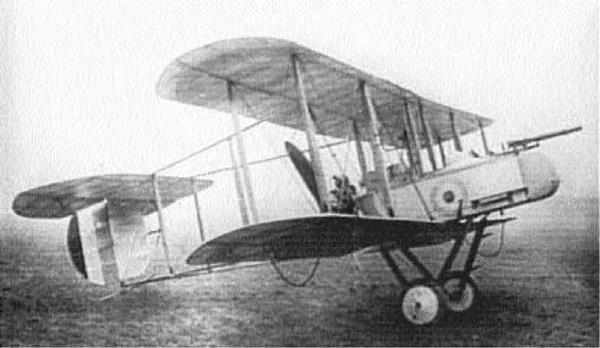

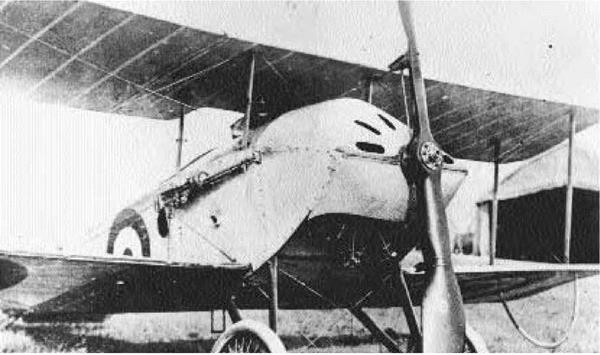

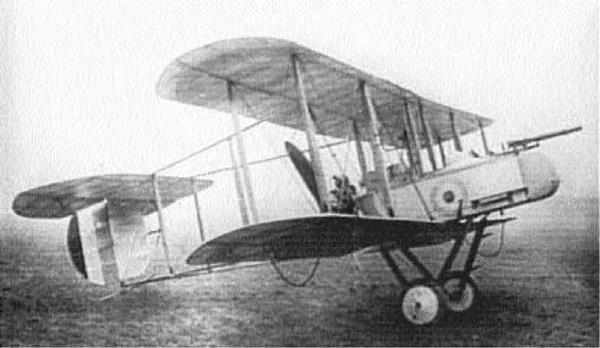

he Tabloid was a fast, groundbreaking design of the early aviation era. In 1914 it became the first single-seat scout to enter military service and also made the first successful air raid on German soil.

In 1913 Tommy Sopwith established a small aircraft firm at Kingston-upon-Thames and commenced his lifelong ambition of designing airplanes. His first effort was a small racing biplane named the Tabloid that possessed amazing performance for its day. It was a standard two-bay biplane constructed when monoplanes seemed the future of aviation. Of standard wood-and-fabric construction, it sported a neatly fitting metal cowl and a broad fuselage seating two occupants side by side. The wings were rake-tipped and utilized warping for lateral control. When Harry Hawker flew the Tabloid at the Hendon Air Show on November 29, 1913, he reached a blazing 93 miles per hour and climbed 1,200 feet a minute while carrying a passenger and two and a half hours of fuel! Such outstanding performance quickly garnered military attention, and shortly before World War I the nifty biplane was acquired in

small numbers by both the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service. Around 40 were built, modified to carry ailerons.

Military aircraft at this juncture were little more than civilian flying contraptions pressed into service. However, the speedy Tabloids were among the first aircraft dispatched to France and soon commenced reconnaissance operations. The craft was never formally armed, but on one occasion a Tabloid piloted by Lieutenant Norman Spratt forced a German machine down by constantly circling it! A more ominous action transpired on October 8, 1916, when two Tabloids flown by Commander Spenser Gray and Lieutenant Marix conducted the first allied bomb run over Germany. Spenser became lost in the mist and dropped his small bombs on the Cologne railway station, but Marix enjoyed spectacular success by destroying Zeppelin Z IX in its shed. Following some brief Mediterranean service, the famous Tabloids were finally retired. But Tommy Sopwith had made his mark and went on to become a renowned aircraft manufacturer.

|

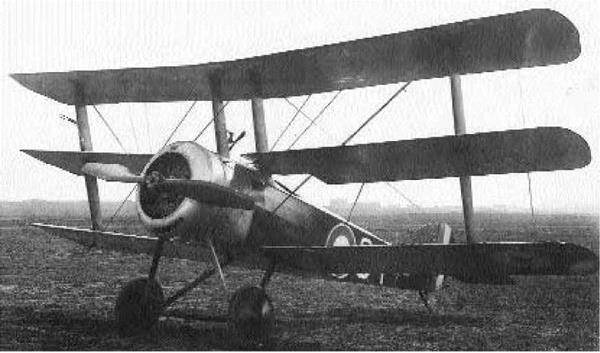

Type: Fighter

|

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 26 feet, 6 inches; length, 18 feet, 10 inches; height, 10 feet, 6 inches Weights: empty, 1,101 pounds; gross, 1,541 pounds Power plant: 1 x 130-horsepower Clerget rotary engine

Performance: maximum speed, 117 miles per hour; ceiling, 20,500 feet; range, 250 miles Armament: 1 x.303-inch machine gun Service dates: 1917

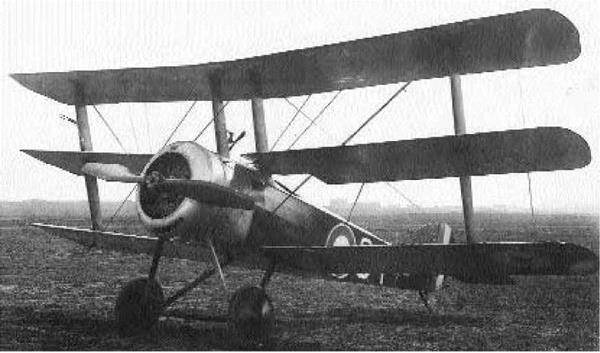

oming on the heels of the vaunted Pup, the Sopwith Triplane was an even bigger surprise to the Germans. The little Tripehound was faster and could outturn and outclimb the Albatros scouts with ease.

The Sopwith Triplane originated when Herbert Smith attempted to wring even more maneuverability out of his exiting Pup design. The prototype flew in May 1916 and shared some outward similarities with the earlier machine, but little else. Like the Pup, the Triplane was compact and good-looking. It employed three wings of equal length, but each was fitted with an aileron to enhance turning and roll rates. Being a triplane, the wings were also of less chord, which gave the pilot better fields of vision. The fuselage was conventionally built of wood and fabric with the engine, armament, fuel, and pilot concentrated toward the front. This arrangement, in concert with torque forces from the spinning rotary engine, contributed to its very sharp turning rate. Trial flights were successful, and the Triplane was

ordered in quantity for both the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service. A majority of the 140 Triplanes constructed were flown by navy pilots, who dubbed it the Tripehound.

The little Sopwiths appeared on the Western Front in the spring of 1917 and completely mastered the formidable Albatros D III scouts. The leading triplane exponent was Lieutenant Raymond Colling – shaw, a Canadian commanding B Flight of Naval Ten. This unit fancied itself the “Black Flight” because all five Triplanes were painted black and christened Black Death, Black Maria, Black Roger, Black Prince, and Black Sheep. In three months of combat, Collingshaw’s flight accounted for no less than 87 German aircraft. Other units enjoyed similar success, and for seven months Tripehounds dominated the air. By the fall of 1917 they were replaced by newer Sopwith Camels and relegated to training duties. The reign of this little Sopwith was brief, but the Germans paid it a direct compliment by bringing out a triplane of their own—the famous Fokker Dr I.

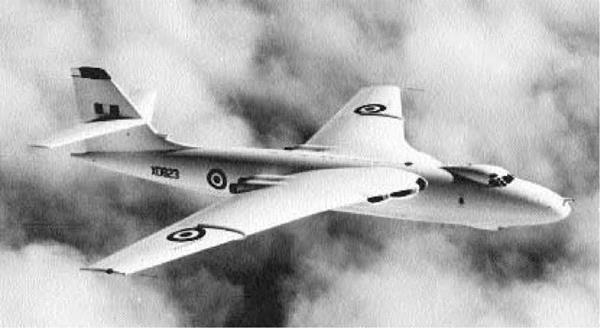

Type: Light Bomber; Trainer

Dimensions: wingspan, 32 feet, 5 inches; length, 40 feet, 2 inches; height, 14 feet

Weights: empty, 6,993 pounds; gross, 13,890 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 4,000-pound thrust Rolls-Royce Viper turbojet engine

Performance: maximum speed, 565 miles per hour; ceiling, 49,200 feet; range, 807 miles

Armament: up to 2,646 pounds of gunpods, bombs, or rockets

Service dates: 1985-

he Super Galeb is a competent trainer/light attack craft that saw active duty during the Yugoslavian civil war. Several were consequently shot down by NATO air forces.

No sooner had the straight-wing G 2 Galeb (Seagull) trainer been deployed in 1970 than the Yugoslavian Federal Air Force began agitating for a more advanced design with greater ground-attack capability. The government, wishing to expand its ties to Third World governments through arms trading, was in complete agreement. By 1978 SOKO, the state-run airplane factory, had unveiled its first G 4 Super Galeb prototype, which shared little commonality with the previous craft beyond the name. It possessed a pointed profile, a swept wing, and tail surfaces that sloped slightly downward. This last feature was unique for a training craft, as the fins were an all-moving arrangement for greater maneuverability. The crew of two sat tandem under a spacious bubble canopy in staggered seats. Production commenced in 1980, and by 1985 the G 4 had largely

superceded the older Galebs as advanced trainers. In service the Super Galeb was reasonably fast and could carry a useful load of ordnance, making it ideal as a cheap strike fighter. Around 130 G 4s were built before production ceased in 1992.

Despite their status as trainers, G 4s acquired a controversial reputation as a ground-attack craft. In 1990 the military government of Myanmar (Burma), beset by guerilla movements, purchased 12 of the sleek craft for counterinsurgency operations. Yugoslavia willingly sold machines in the face of international sanctions against the oppressive local regime. Two years later Super Galebs were in action against Yugoslavians after the civil war commenced. Transferred to the largely Serbian Yugoslav state, G 4s pounded ethnic Muslim civilian centers for some time until ordered by the United Nations to observe a no-fly zone. On February 28, 1994, three Super Galebs disobeyed and were downed in NATO’s first-ever hostile action. It is not known how many G 4s remain operational.

|

Type: Light Bomber

|

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 31 feet, 6 inches; length, 48 feet, 10 inches; height, 14 feet, 7 inches

Weights: empty, 13,007 pounds; gross, 22,267 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 5,000-pound thrust Roll-Royce Viper turbojet engines

Performance: maximum speed, 721 miles per hour; ceiling, 41,010 feet; range, 329 miles

Armament: 2 x 23mm cannons; up to 3,307 pounds of bomb and rockets

Service dates: 1979-

olitics and aviation make for strange bedfellows.

This axiom is borne out in the case of the jointly produced Orao, an indifferent fighter-bomber with great national pride attached.

In 1970 two maverick communist states, Romania and Yugoslavia, announced a decision to jointly develop a new ground-attack aircraft. This move could hardly be viewed as unexpected, as Yugoslavia under Marshal Tito had thumbed its nose at the Soviet Union since 1946. Moreover, Romania’s dictator Nicolae Ceausescu—his country a nominal member of the Warsaw Pact—was a pragmatist determined to forge links outside of the communist bloc. Given the prickly sensibilities of Balkan nationalism, however, each side went to inordinate lengths not to outstage the other. The new craft hoisted a lot of national pride on its back, so, despite common origins, it was also assigned different names! The Romanian version would be designated the IAR 93, whereas its Yugoslavian counterpart became the SOKO J 22 Orao (Eagle).

Early on the two national state aviation industries SOKO and CNIAR elected a relatively simple, if outwardly modern, design. The J 22/IAR 93 was a single-seat, shoulder-wing jet with swept wings and tail surfaces. It was powered by two Rolls-Royce Viper turbojet engines with afterburners, to be manufactured locally. The new craft was destined as a low-level ground-attack machine with possible interception functions. Plans were also entertained to produce a two-seat trainer version. Construction moved forward haltingly, and it was not until October 31, 1974, that two prototypes flew—on the same day in both countries. Production had finally geared up by 1979, and the first models arrived for service shortly thereafter. The initial machines lacked afterburners and were immediately consigned to reconnaissance duties. Subsequent models were fitted with the thrust-enhancing device, but even that addition did not translate into supersonic performance. Consequently, the Orao remains a poor man’s attack plane. Romania has acquired about 200, but Yugoslavian production halted at about 50 after that country splintered in 1995.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 26 feet, 6 inches; length, 20 feet, 4 inches; height, 7 feet, 8 inches Weights: empty, 1,255 pounds; gross, 1,808 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 220-horsepower Hispano-Suiza liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 138 miles per hour; ceiling, 21,800 feet; range, 220 miles Armament: 2 x 7.7mm machine guns Service dates: 1916-1923

he magnificent SPAD XIII was the best French fighter of World War I and a radical departure from earlier design philosophies. Although not as nimble as the lighter Nieuports, the sacrifice in maneuverability was offset by speed and ruggedness.

In 1916 the inability of the Societe Pour les Appareils Deperdussin (SPAD) to market the SPAD A 1 two-seat fighter induced designer Louis Bechereau to rethink his approach. In April 1916 his prototype SPAD VII emerged as a completely new aircraft sporting beautifully clean lines. It was a conventional biplane with unstaggered, four-bay wings and a round cross-section fuselage housing a 160-horsepower in-line V engine. Armament was restricted to one machine gun. Test flights proved the SPAD VII possessed great speed and strength, so the craft entered service within months. The new fighter was immediately successful, being faster than German fighters in both climb and level flight. Moreover, SPAD VIIs could absorb amazing amounts of damage and return safely. By 1917 more than 5,000 had been produced, and they equipped

virtually every French fighter squadron, along with many in Italy, Belgium, and Russia. Reputedly, Italian ace Francesco Baracca grew so attached to his SPAD VII that he refused to trade it when later models became available.

In 1917 Bechereau capitalized on his success by developing the mighty SPAD XIII. This was a further refinement of his earlier masterpiece, with two machine guns, longer wings, and a stronger engine. In combat the SPAD XIII repeated the success of the earlier design, and it became the chosen mount of numerous French aces such as Rene Fonck, Georges Guynemer, and Charles Nungesser. By 1918 more than 8,472 had been constructed, equipping no less than 71 French squadrons. It also replaced rickety Nieuport 28s of the American Expeditionary Force and was flown with great success by Captain Eddie Rickenbacker. More than any other airplane, the SPAD XIII helped turn the air war’s tide in favor of the Allies. Afterward it was widely exported abroad and continued in frontline service for nearly a decade.

|

Type: Light Bomber

|

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 45 feet, 3 inches; length, 61 feet, 6 inches; height, 16 feet, 5 inches

Weights: empty, 36,155 pounds; gross, 42,989 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 24,802-pound thrust NPO Saturn AL-21F-3 turbojet engine

Performance: maximum speed, 870 miles per hour; ceiling, 49,870 feet; range, 715 miles

Armament: 2 x 30mm cannons; up to 2,205 pounds of bomb or rockets

Service dates: 1971-

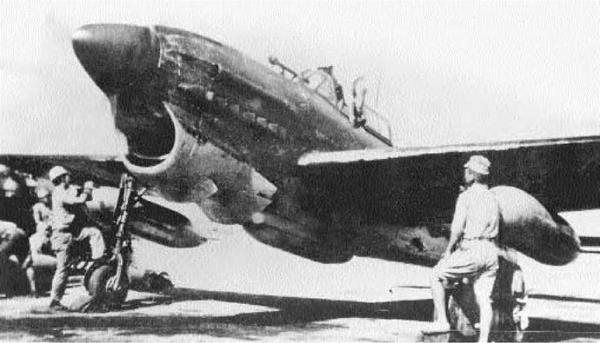

ussian aircraft builders display great ingenuity in wringing every last ounce of performance from existing machines. The long-lived Su 17 is such an example, and it continues to be upgraded and employed long after the basic design became obsolete.

In 1956 the Sukhoi design bureau created its first tactical jet bomber, the Su 7, a modern-looking machine built in large numbers to offset its relative simplicity. It was a capable fighter-bomber and ruggedly built but also somewhat underpowered. Moreover, it suffered from long runway rolls and rather short range. In 1967 the Sukhoi bureau decided to upgrade this family of bombers by adding variable-geometry wings to enhance takeoff, landing, and load-carrying abilities. Early on it was judged impossible to fit wing-retracting equipment into the narrow fuselage, so engineers compromised by making the wings pivot midway along their length. The added lift increased the Su 7’s takeoff performance, and operational radius and ordnance payload were improved as well. Commencing in

1971 the new Su 17 became operational in large numbers, and they were deployed by Warsaw Pact allies and Soviet client states. It has since received the NATO designation FITTER.

During the past three decades, the basic Su 17 design has undergone numerous modifications and upgrades that render this marginally obsolete machine still useful as an attack craft. The latest variant, the Su 17M, is distinguished by a close-fitting clamshell canopy with a high spine ridge running the length of the fuselage. The tail fin is also somewhat taller and employs a single airscoop at its base. This model has been exported abroad as the Su 22, with somewhat lowered-powered avionics, but otherwise it remains an effective bombing platform. After the breakup of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s, many former Warsaw Pact countries were eager to unload their aging Sukhois, but Russia alone seems content to maintain its stable of 800-plus Su 17s. Their rugged design, combined with good reliability and performance, ensures a long service life.

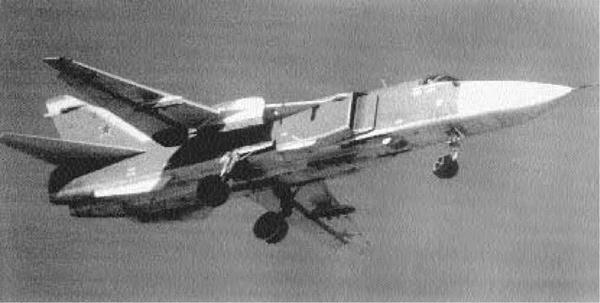

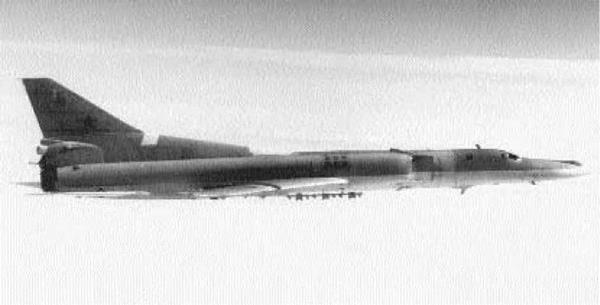

Type: Medium Bomber; Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, (spread) 57 feet, 10 inches; length, 80 feet, 5 inches; height, 16 feet Weights: empty, 41,887 pounds; gross, 87,522 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 24,802-pound thrust NPO Saturn AL-21F-3A turbofan engines Performance: maximum speed, 1,441 miles per hour; ceiling, 57,415 feet; range, 1,300 miles Armament: 1 x 23mm cannon; up to 17,637 pounds of nuclear or conventional bombs Service dates: 1974-

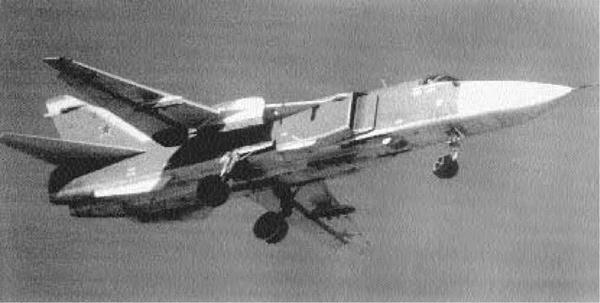

he formidable Su 24 is among the most potent weapons of the Russian tactical air arm. It can attack at low level, high speed, and with pinpoint accuracy under any weather conditions.

Up through the late 1960s, Soviet tactical aviation, though possessing huge quantities of airplanes, still lacked genuine nighttime all-weather attack capability. Moreover, in view of the increasing sophistication of antiaircraft defenses, low-level operations were becoming a matter of survival. The existing Il 28 and Yak 28s then in service were simply too old or too incapable to meet such rigorous standards. To remedy this shortfall and place the Red Air Force on par with Western adversaries, the Sukhoi design bureau was entrusted with designing a new generation of ground-attack craft. Commencing in 1970 it experimented with a bizarre variety of delta and vertical-takeoff prototypes before settling on a machine very reminiscent of the General Dynamics F-111. Like that groundbreaking U. S. design, the new Su 24 employed variable-geometry wings

that sweep forward to assist takeoff and landings, then sweep back for high-speed operations. Around 900 were constructed since 1974, and they received the NATO code name FENCER.

In service the Su 24s were the first Russian aircraft to incorporate a totally integrated avionics system, one linking bombsight, weapons control, and navigation into one central computer. The new Su 24, in fact, was initially viewed as a “mini-F-111” owning to the obvious side-by-side placement of the two-member crew. This was proof that a Soviet warplane, for the first time, flew with a dedicated weapons-systems officer to operate an advanced avionics suite. Approaching a target at low altitude and high speed, Su 24s can deliver a host of conventional or nuclear weapons with great accuracy at night and in bad weather. An equally adept tactical reconnaissance version, the Su 24MR, has also been developed. With continual upgrades, these formidable warplanes will remain in service for years to come.

|

Type: Antitank; Light Bomber

|

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 47 feet, 1 inch; length, 50 feet, 11 inches; height, 15 feet, 9 inches

Weights: empty, 21,605 pounds; gross, 41,005 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 9,921-pound thrust NMPK R-195 turbojet engines

Performance: maximum speed, 590 miles per hour; ceiling, 22,965 feet; range, 308 miles

Armament: 1 x 30mm cannon; up to 9,700 pounds of bombs or rockets

Service dates: 1984-

he Su 25 is successor to the famous Il 2 Shtur – movik of World War II. Fast and heavily armed, it is reputedly the most difficult plane in the world to shoot down.

The air war in Vietnam highlighted the need for simple close-support aircraft able to operate from unpaved strips close to the front. Such warplanes would also have to deliver heavy ordnance against targets with great accuracy and be able to survive intense ground fire. The United States parlayed its experience into the Fairchild A-10 Thunderbolt II, a heavily armored twin-engine bomber. The Soviets also watched these developments closely before deciding that they, too, needed similar aircraft and capabilities. During World War II Russia had deployed the redoubtable Il 2 Shturmovik aircraft for identical reasons, so in 1968 the Sukhoi design bureau became tasked with developing an equivalent machine for the jet age. The bureau settled upon a design reminiscent of the Northrop YA-9, which had lost out to the A-10 in competition. The new Su 25 was an all-metal,

shoulder-wing monoplane constructed around a heavily armored titanium “tub” that housed both pilot and avionics. Engines were placed in long, reinforced nacelles on either side of the fuselage, and the fuel tanks were filled with reticulated foam for protection against explosions. To assist slow-speed maneuvering, the wingtip pods split open at the ends to form air brakes. Its profile is rather pointed, but a blunt noseplate covers a laser range finder/target designator. The Su 25 is somewhat faster than the A – 10, trusting more in speed to ensure survival than a dependency on agility and heavy armor. It is nonetheless an effective tank destroyer.

A series of preproduction aircraft was subsequently deployed to Afghanistan, where the planes performed useful service against guerilla forces. They flew some 60,000 sorties, losing 23 machines in the process, but the decision was made to enter production in 1980. Since then 330 Su 25s have been built; they have received the NATO designation FROGFOOT.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 48 feet, 3 inches; length, 72 feet; height, 19 feet, 6 inches Weights: empty, 38,580 pounds; gross, 72,750 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 27,557-pound thrust Saturn/Lyulka AL-31F turbofan engines Performance: maximum speed, 1,553 miles per hour; ceiling, 59,055 feet; range, 2,285 miles Armament: 1 x 30mm cannon; up to 10 air-to-air missiles Service dates: 1985-

he fantastic Su 27 is probably the world’s most impressive interceptor. Fast, capable, and heavily armed, it was the first aircraft to perform the famous “cobra” maneuver.

By 1969 the forthcoming generation of U. S. fighters—the Grumman F-14 Tomcat and the Mc – Donnell-Douglas F-15 Eagle—caused great consternation within Soviet aviation circles. These new planes were projected to be faster, more maneuverable, and able to carry more missiles than their Russian counterparts. That year Pavel Sukhoi began development of a fighter-interceptor with the range, armament, and ultramodern avionics to counter them. It was imperative that the new craft be able to detect and intercept low-flying targets and meet agile U. S. fighters on equal terms. Several unsuccessful prototypes were developed before Sukhoi died; his successor, Mikhail Simonov, hit upon a functional solution. The new Su 27 was a big fighter by virtue of the 4-foot-wide radar dish utilized in the nose. It also employed widely separated twin turbofan engines in a beautifully blended forebody and

high-lift wing. The craft was deliberately made unstable for enhanced maneuverability and is flown with computer-assisted fly-by-wire technology. Moreover, the Su 27 does not require in-flight refueling, as it carries 10 tons of fuel aloft. The NATO code word for the big craft is FLANKER, a name adopted by Russian pilots themselves.

In 1986 pilot Viktor Pugachev impressively flew an Su 27 from Moscow to the Paris Air Show nonstop, then stunned observers by demonstrating the famous “cobra” maneuver. In this acrobatic stunt, the pilot raises the nose of the Su 27 at high speed until the aircraft virtually stands still on its tail in midair; the pilot then lowers it without loss of altitude—the effect is a cobralike appearance. In service the FLANKER is designed for long-range interception, being the first Russian fighter unshackled from ground-controlled intercept radar. It can launch up to 10 missiles before closing in for the kill with a heavy cannon. China, wishing to replace its aging fighter fleet, purchased several for its own air force. The Su 27 is a formidable fighting machine and will remain so for years.

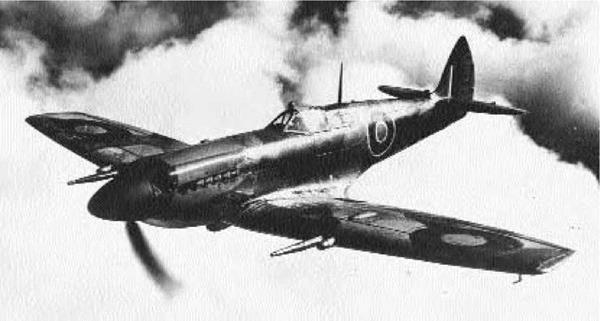

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 36 feet, 10 inches; length, 32 feet, 8 inches; height, 12 feet, 8 inches Weights: empty, 6,600 pounds; gross, 8,500 pounds

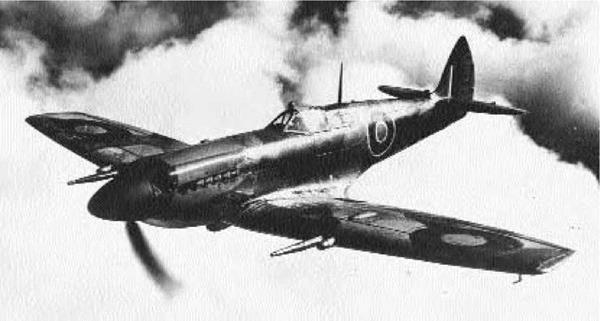

Power plant: 1 x 2,050-horsepower Rolls-Royce Griffon liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 448 miles per hour; ceiling, 44,500 feet; range, 460 miles Armament: 2 x 20mm cannons; 4 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 500 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1938-1954

he immortal Spitfire remains the symbol of British aerial prowess during World War II. Beautiful, fast, and lethal, this thoroughbred warrior was the quintessential fighter pilot’s dream—and more.

Reginald J. Mitchell was an accomplished designer of racing craft when, in 1934, he set about designing Britain’s first all-metal eight-gun fighter. His initial attempt, to be named the Spitfire, was a crank-winged apparition that flew as bad as it looked. However, development continued as a company project. The revised machine was a rakish, highly streamlined aircraft with a pointed spinner, retractable undercarriage, and beautiful elliptical wings. It exuded the persona of a racehorse. The new Spitfire flew just less than 350 miles per hour, making it the fastest fighter in the world. Moreover, its handling and maneuverability were intrinsically superb, traits that carried over through a long and exemplary service life. The usually dubious British Air Ministry was so singularly impressed by the craft that a new specification was issued “around it” to facilitate production. Spitfire Is entered squadron ser

vice in 1938, and the following year, when Europe was plunged into war, they constituted 40 percent of Britain’s frontline fighter strength.

Commencing with the 1940 Battle of Britain, Spitfires captured the imagination of the world. They fought the equally capable Messerschmitt Bf 109Es to a draw, leaving the more numerous Hawker Hurricanes to drub bomber formations. As the war developed, so did the Spitfire, into no less than 40 major versions. Prior to 1941 they were indelibly associated with the equally famous Rolls – Royce Merlin engine, but the appearance of the Focke-Wulf Fw 190 in 1942 caused better engines to be sought. Eventually the powerful Griffon in-line engine was married to the Spitfire fuselage, endowing it with greater speed and climb without infringing upon its legendary handling. The new Spitfire XIV was so fast that it successfully engaged the dreaded Me 262 jet fighters, downing several. The last marks were assembled in 1947 and remained in service until 1954. More than 20,000 of these peerless warriors were built.

|

Type: Patrol-Bomber

|

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 85 feet; length, 54 feet, 10 inches; height, 21 feet, 9 inches

Weights: empty, 11,250 pounds; gross, 19,000 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 875-horsepower Bristol Pegasus X radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 165 miles per hour; ceiling, 18,500 feet; range, 1,000 miles

Armament: 3 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 1,000 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1938-1942

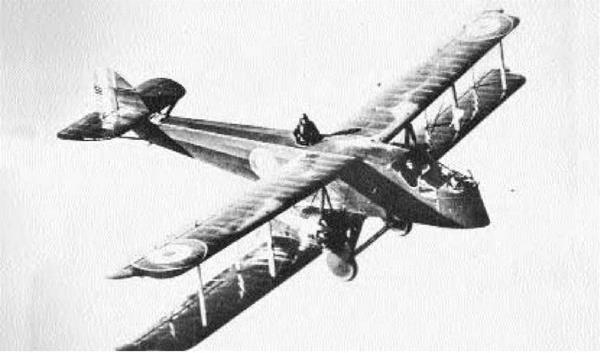

he Stranraer was the last in a dynasty of flying boats that spanned the interwar period. It was also the fastest flying boat ever employed by the Royal Air Force.

In 1924 the British Air Ministry released specifications for a new biplane flying boat to replace the World War I-vintage Felixstowe F5. The following year, Reginald J. Mitchell, future designer of the legendary Spitfire, conceived a new machine based upon his successful Supermarine Swan, a civilian machine. Christened the Southampton, 78 machines were manufactured for the Royal Air Force. The Mk II variant sported an all-metal hull, and in 1927-1928 Southamptons of No. 205 Squadron successfully completed a 27,000-mile tour of the Far East. They served capably for nearly a decade before being supplanted by a more refined model, the Scapa, in 1933. This machine bore many similarities to its forebear but differed in having double rudders, a fully enclosed cockpit, and relocated engines at the bottom of the top wing. By 1935 15 ex

amples had been delivered; they were withdrawn by 1938.

In 1931 the government drew up specifications for a new all-purpose flying boat. Mitchell created a scaled-up version of the Scapa that was initially designated the Southampton V. It was longer than the Scapa, with an extra set of interplane struts and a tailgunner position. The prototype was powered by two Bristol Pegasus IIIM engines driving two-blade wooden propellers, but production models utilized three-blade metal ones. Consequently, the new craft, which was renamed the Stranraer, became the fastest flying boat ever acquired by the RAF. A total of 24 were delivered in 1935, but Stranraers were rapidly overtaken by technology and soon rendered obsolete. They actively patrolled in 1939, but the following year gave way to greatly superior Short Sun – derlands. However, Stranraers received a second lease on life in 1941 when the Royal Canadian Air Force acquired an additional 47 examples. They performed coastal patrolling until being retired in 1944.

Type: Air/Sea Rescue; Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 45 feet, 10 inches; length, 37 feet, 3 inches; height, 15 feet, 3 inches

Weights: empty, 4,900 pounds; gross, 7,200 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 775-horsepower Bristol Pegasus radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 135 miles per hour; ceiling, 18,500 feet; range, 600 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 760 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1936-1945

he homely “Shagbat” was one of the most welcome sights in the skies of World War II. It rescued thousands of downed airmen and performed useful service as a naval gunnery spotter.

As early as 1921 Reginald J. Mitchell had designed a small flying boat that he deemed the Seagull. It continued on as a private venture for many years until 1933, when the Australian government purchased 24 examples of the latest version, the Seagull

V. This craft was ugly but functional. It was a singlebay biplane with a fuselage mounted below the lower wing; a pusher-configuration engine stood affixed on struts above it. The hull was made of metal and stressed for shipboard catapulting and, hence, very strong. Flying surfaces were all fabric-covered, and there was a fully enclosed cockpit and two gunner positions. At this time the Fleet Air Arm closely scrutinized Mitchell’s creation and in March 1936 adopted it as the Walrus I. They were deployed on capital ships throughout the fleet and engaged in reconnais

sance and gunnery spotting. Once fitted with fixed landing gear, the little amphibians could also operate from airstrips. As events proved, the Walrus was adept at convoy patrolling and antisubmarine warfare. A total of 287 Walrus Is were produced.

During World War II the ubiquitous Walrus served in virtually every theater of the war. Antiquated appearances notwithstanding, it was a tough little craft capable of absorbing great amounts of punishment. In addition to naval service, Shagbats also equipped numerous squadrons of the Royal Air Force Air/Sea Rescue Service. This force was responsible for saving thousands of downed airmen, and its stately gait and noisy drone were reassuring sights in the combat theaters. By 1940 a new version, the Walrus II, was introduced, with a completely wooden hull. Production of Mk IIs amounted to 453 machines, with many serving in the Australian, New Zealand, and other Commonwealth navies. Most were phased out shortly after 1945.

|

Type: Light Bomber

|

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 66 feet, 8 inches; length, 40 feet, 3 inches; height, 10 feet, 8 inches

Weights: empty, 10,511 pounds; gross, 17,372 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 960-horsepower M-103 liquid-cooled in-line engines

Performance: maximum speed, 280 miles per hour; ceiling, 25,590 feet; range, 1,429 miles

Armament: 6 x 7.62mm machine guns; 1,323 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1936-1943

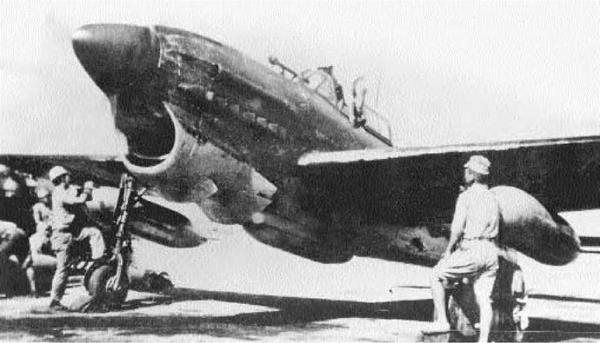

ast-flying SB 2s were among the world’s best bombers when they appeared in 1936. They enjoyed a distinguished career in Spain, Mongolia, and Finland before suffering heavy losses in World War II.

In 1933 the Soviet government announced specifications for an entirely new light bomber, one so fast that it could operate without escort fighters. The Tupolev design bureau finessed the problem with great skill, and in 1934 it built two prototypes with radial and in-line engines respectively. The new SB 1 was Russia’s first stressed-skin aircraft, a midwing, all-metal monoplane bomber. It was modern in every respect to Western contemporaries and possessed such advanced features as retractable landing gear and flush-riveting. A crew of four was comfortably housed, and the plane flew faster than any fighter or bomber then in service, including the highly touted Bristol Blenheim. In 1936 the in-line – engine prototype entered production as the SB 2, and nearly 7,000 were produced. These modern, capable craft formed the bulk of Soviet tactical aviation over the next five years and played a major role

in modernizing and revitalizing the Soviet bomber forces.

SB 2s were bloodied in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), where they proved impervious to slower Nationalist fighters. They also enjoyed similar success in Mongolia against the Japanese and were exported to China in quantity. Several new versions were also introduced with more powerful engines, but this robust design was growing obsolete in light of developments elsewhere. SB 2s again fought well against Finland during 1939-1940, but when Germany invaded Russia the following year they lost their speed advantage. Being somewhat flammable, scores were quickly dispatched by formidable Messerschmitt Bf 109 and Bf 110 fighters. But they were abundantly available, and so the Soviets had little recourse but to continually employ them. They did so in a wide variety of roles, including that of night intruder and torpedo-bomber. By the time SB 2s withdrew in 1943, they had sustained the heaviest losses of any Russian aircraft in World War II.

|

Type: Heavy Bomber

|

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 132 feet, 10 inches; length, 82 feet, 8 inches; height, 18 feet

Weights: empty, 22,000 pounds; gross, 54,020 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 730-horsepower M-34R liquid-cooled in-line engines

Performance: maximum speed, 179 miles per hour; ceiling, 25,365 feet; range, 1,550 miles

Armament: 4 x 7.62mm machine guns; up to 12,790 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1931-1944

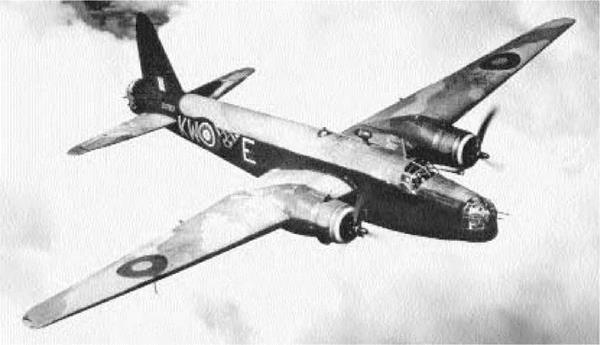

he mighty TB 3 was the world’s most advanced heavy bomber throughout most of the early 1930s. Despite archaic looks, it was a solid, capable design and served admirably through most of World War II.

Russian proclivities for giant aircraft dated back to the Sikorsky Ilya Muromets of 1914, and in time they accumulated sufficient knowledge and expertise to build even bigger machines. In 1925 Andrei N. Tupolev fielded the TB 1, an advanced metal monoplane that was the best in its class. Three years later he received orders to build a four-engine bomber with prodigious range and lifting abilities. He complied, and the new TB 3 emerged as an allmetal, low-wing monoplane with fixed landing gear and a crew of ten. Initial models were covered in corrugated metal, stressed to great strength. Consequently, in 1931 the TB 3 could lift more than 12,000 pounds on short flights—a payload unmatched until the Avro Lancaster and Boeing B-29 Superfortress a decade later. Stalin appreciated the propaganda

value of such huge machines, and during the 1934 May Day parade no less than 250 TB 3s overflew Moscow. The production run concluded by 1938 with 808 machines built, with latter versions possessing smooth, stressed skin.

In service the TB 3s proved ruggedly adaptable and easily maintained. They made international headlines by transporting scientific teams during a number of expeditions to the Arctic Circle. TB 3s were also used during the mid-1930s to train embryonic Soviet parachute forces, who deployed by jumping off the aircraft’s broad wing. An even more controversial use was the so-called parasite experiments, whereby the lumbering craft carried their own fighter escorts. One TB 3 could successfully carry, launch, and retrieve no less than three I 15 biplanes and two I 16 monoplanes. The giant craft was marginally obsolete at the start of the 1941 German invasion and, being vulnerable to enemy fighters, served as a night bomber and transport. All these versatile machines were retired from service by 1944.

|

Type: Medium Bomber

|

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 61 feet, 10 inches; length, 45 feet, 3 inches; height, 13 feet, 9 inches Weights: empty, 18,524 pounds; gross, 28,219 pounds Power plant: 2 x 1,850-horsepower Shvetsov radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 342 mile per hour; ceiling, 31,170 feet; range, 1,553 miles Armament: 1 x 12.7mm machine gun; 2 x 20mm cannons; up to 5,004 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1944-1961

he Tu 2 was a Soviet medium bomber that compiled an impressive record in World War II. Its success is especially remarkable considering that it was designed in a prison.

In 1937 the Russian aircraft engineer Andrei Tupolev was accused of passing secrets to the Germans and was incarcerated in a Soviet gulag. He and his entire staff languished for two years until they obtained promises of early release in exchange for designing a new bomber for the Red Air Force. Work commenced from behind prison walls, and in January 1941 the prototype first flew. It was designated “Aircraft 102,” for Tupolev’s status as a nonperson precluded using his initials! The new machine was a strikingly clean, twin-engine design with smooth engine cowlings, a pointed profile, and twin rudders. During flight tests it demonstrated even better performance than the Petlyakov Pe 2s then in service. It was slow going at first, but the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 dramatically accelerated the pace of production.

The Tu 2 proved itself a fine machine, especially in terms of speed, payload, and handling. The big, rugged craft was especially popular with crews for its amazing ability to absorb damage and remain aloft. Initial deliveries did not commence until late 1944, and then in only limited numbers. This was because the Tu 2 was more complicated to build than the Pe 2 and took longer to assemble. Another reason is that the Pe 2 was already serving capably— and in large numbers—so Tupolev’s new machine did not receive priority production. Nonetheless, by 1945 Tu 2s were a common sight in the skies over Eastern Europe, and they had a devastating effect upon German troops and armor. Consequently, Tupolev was rehabilitated and received the Stalin Prize for his achievement. Tu 2s remained in production until 1948, following a production run of 2,557 machines. Forces under the United Nations encountered them during the Korean War in 1950, and Tu 2s also flew with communist satellite air forces until 1961.

|

Type: Medium Bomber; Reconnaissance

|

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 108 feet, 3 inches; length, 14 feet, 2 inches; height, 34 feet

Weights: empty, 82,012 pounds; gross, 167,110 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 20,920-pound thrust Mikulin RD-3m-500 turbojets

Performance: maximum speed, 616 miles per hour; ceiling, 40,350 feet; range, 4,000 miles

Armament: 6 x 23mm cannons; up to 6,600 pounds of nuclear bombs or standoff missiles

Service dates: 1955-

ne of the classic aviation designs of the 1950s, the Tu 16 was Russia’s most successful jet bomber. It remains in active service today as a missile platform and maritime reconnaissance craft.

The origins of the famous Tu 16 trace back to 1944, when bad weather forced down three U. S. Boeing B-29s on a Russian airfield in Siberia. The Soviet Union, neutral toward Japan, promptly detained the crews and confiscated the aircraft. This technological windfall handed Soviet dictator Josef Stalin the world’s most advanced bomber aircraft, and he immediately ordered reverse-engineered copies for the Red Air Force. They became known as the Tupolev Tu 4 and received the NATO designation BULL. By 1950 the Americans and British were developing and deploying advanced jet-powered bomber designs, so Stalin authorized production of Soviet models as well. The new Tu 16 thus became the first successful Soviet jet bomber, the first with swept-back wings, and the first with engines buried

in the wing roots. It was revealed to the West in 1954 as a midwing aircraft of extremely sleek lines. The landing gear were uniquely positioned in trailing- edge pods, as the wing was too thin to contain them. Tupolev’s conservative approach gave the Tu 16 a robust construction that in turn led to a long and varied service life. Around 2,000 were manufactured and given the NATO code name BADGER.

Initial models of the Tu 16 were tactical nuclear bombers, but, lacking the necessary range to hit the United States, they were quickly phased out by more modern designs. Most were shunted over to the Soviet navy, which employed them in long-range reconnaissance and antishipping strike roles. Many BADGERS encountered at sea were usually configured with one or more cruise missiles in the bomb bay or under the wings. The type was also exported to China in the late 1950s and was produced there in some quantity. An estimated 70 Tu 16s fly with Russian naval aviation and will continue serving for years to come.

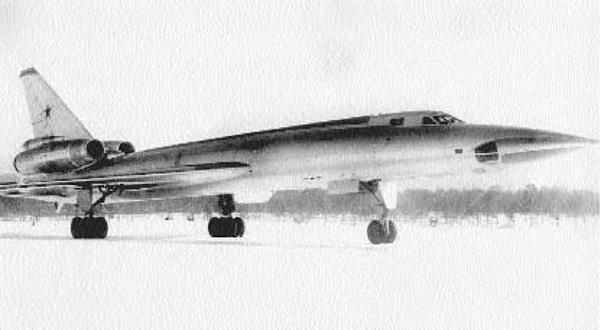

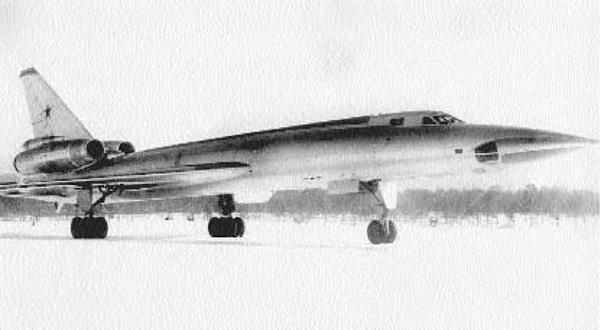

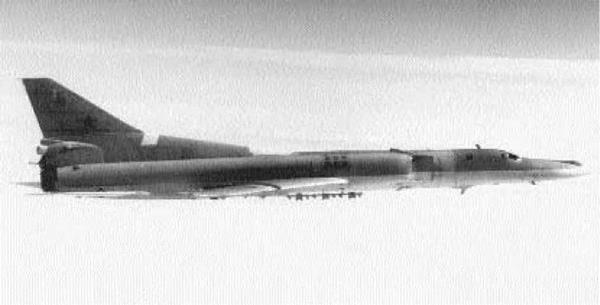

Type: Medium Bomber; Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 77 feet; length, 139 feet, 9 inches; height, 35 feet

Weights: empty, 83,995 pounds; gross, 207,230 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 27,560-pound thrust Dobrynin RD-7M-2 turbojet engines

Performance: maximum speed, 920 miles per hour; ceiling, 43,365 feet; range, 2,600 miles

Armament: 2 x 23mm cannons; up to 22,046 pounds of nuclear weapons or missiles

Service dates: 1961-

he Tu 22 was the Soviet Union’s first supersonic bomber. Hobbled by poor range, it spent most of a long life as a maritime reconnaissance platform or performing antishipping functions.