. Flettner Fl 282 Kolibri

Type: Reconnaissance

Dimensions: rotorspan, 39 feet, 4 inches; length, 21 feet, 6 inches; height, 7 feet, 2 inches

Weights: empty, 1,411 pounds; gross, 2,205 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 140-horsepower Siemens-Halske air-cooled engine

Performance: maximum speed, 68 miles per hour; ceiling, 12,992 feet; range, 106 miles

Armament: none

Service dates: 1943-1944

|

T |

he diminutive Kolibri was the first combat-capable helicopter to reach mass production. Despite primitive appearances, it was perfectly functional and a harbinger of things to come.

Anton Flettner, one of Europe’s most accomplished helicopter pioneers, built his first functioning machine in 1932. A succession of prototypes culminated in his Fl 184 autogyro of 1935, which was ordered by the German Kriegsmarine (navy) for evaluation. It was driven by a single three-blade rotor, with two smaller antitorque propellers on either side. Around this time, however, Flettner developed interest in counter-rotating, intermeshed, twin-rotor designs. Such a machine would cancel out the effects of torque and the need for other stability devices. In 1939 he perfected his Fl 265 Kolibri (Hummingbird), which was a small yet perfectly functional helicopter. The fuselage was made of steel tubing covered with metal skin and possessed a large rudder with dihedral tailplanes. The craft was driven by two shafts, spread apart from each other at divergent angles behind the pilot’s seat. Both blades, made from steel

tube and plywood covering, were closely inter – meshed with each other at all speeds for greater stability. Reputedly, a pilot could hover indefinitely with his hands off the controls. The Fl 282—designed with maritime reconnaissance in mind—carried a backward-facing observer behind the shafts. By 1941 several prototypes had flown with impressive results, and that year it entered into production.

It was the Kriegsmarine’s intention to obtain up to 1,000 Fl 282s for antisubmarine work from the decks of warships. However, less than two dozen were actually completed, but they saw extensive service in the Baltic and Mediterranean Seas. As flying platforms, the tiny helicopters were impressive because they could alight safely in all kinds of weather conditions. One even landed on a pitching turret top of the cruiser Koln during a storm. By war’s end, only three examples of the Fl 282 survived intact. Two of these visionary machines were shipped off to the United States for evaluation, and one remains on display at the U. S. Air Force Museum in Dayton, Ohio.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 47 feet, 7 inches; length, 46 feet, 9 inches; height, 17 feet, 7 inches

Weights: empty, 8,900 pounds; gross, 14,991 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 988-horsepower Turbomeca XVIG turboprop engines

Performance: maximum speed, 311 miles per hour; ceiling, 31,825 feet; range, 2,305 miles

Armament: 4 x.30-caliber machine guns; 2 x 20mm cannons; 3,307 pounds of ordnance

Service dates: 1976-

|

T |

he famous Pucara is a versatile counterinsurgency aircraft and the first to originate from a Latin American country. It failed to accrue distinction during the 1982 Falkland Islands War and has since been declared surplus.

During the late 1960s, South America was rocked by numerous revolutionary groups, inspired and frequently financed by the communist bloc. In 1969 the Argentine government approached Fabrica Militar de Aviones in Cordoba to devise a heavily armed light strike aircraft capable of dealing with fast-moving guerillas. After some preliminary testing with glider models, the first prototype lifted off in August 1969, at which point the Fuerza Aerea Argentina (Argentine air force) ordered it into production as the FMA IA 58 Pucara. The name refers to a stone stronghold erected by indigenous Indians of the Andes. The Pucara is an extremely handsome craft with a low-mounted wing and a high-“T” tail section. It is entirely made of metal and seats two crew members under a spacious canopy, with the

pilot enjoying excellent frontal vision over a sharply downswept nose. It is also heavily armed, mounting two cannons, four machine guns, and a host of underwing ordnance. The first IA 58s became operational in 1974 and were deployed with good effect against communist guerillas operating in the Tu – cuman region of the country. Its impressive performance led to small orders from neighboring Columbia and Paraguay for similar purposes.

The Pucara is best known for the limited role it played during the 1982 Falkland Islands War with England. Once those islands had been seized in 1981, a force of no less than 24 IA 58s was deployed there to defend them. However, counterattacking British forces shot down several, and more were destroyed in nighttime raids by the Special Air Service. One Pucara was captured intact and is currently displayed at the Imperial War Museum in London. After this episode, Argentina lost interest in the craft, and most have been laid up in surplus. Around 100 have been built.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 60 feet, 4 inches; length, 39 feet, 4 inches; height, 10 feet, 2 inches Weights: empty, 5,930 pounds; gross, 8,708 pounds Power plant: 2 x 465-horsepower Argus air-cooled engines

Performance: maximum speed, 217 miles per hour; ceiling, 23,950 feet; range, 416 miles Armament: 3 x 7.92mm machine guns; up to 440 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1940-1945

|

T |

he unattractive Uhu was the “eyes” of the German army in campaigns from Finland to Africa. Despite appearances, the craft was strong, maneuverable, and difficult to shoot down.

Since its inception, the Luftwaffe was basically viewed as a tactical appendage to the Wehrmacht, and reconnaissance aircraft were consequently an essential commodity. In 1937 the German Air Ministry issued specifications for a new short-range reconnaissance craft to replace its aging fleet of Heinkel He 46s. Of three firms to respond, the Focke – Wulf Flugzeugbau firm under Dr. Kurt Tank submitted an unorthodox design that was initially greeted with skepticism. The Fw 189 was a low-wing, twin – boom design of metal construction. A crew of three sat in a spacious, glazed fuselage pod affording them excellent visibility. Each of the thin booms mounted a single engine, and they were joined together aft by a single tailplane. Twin-boomed aircraft were not unknown in military circles, but German authorities initially viewed Tank’s creation with suspicion. However, flight-testing proved extremely successful, and

the big craft demonstrated ample strength and maneuverability for the tasks at hand. Production commenced in 1939, and a total of 846 Fw 189s were built. Crew members unofficially dubbed it the Uhu (Owl), but Nazi propagandists touted it as Die Fliegender Auge, or “The Flying Eye.”

In 1940 the Fw 189 saw its baptism of fire along the Eastern Front, where most were stationed. At least one squadron of Uhus also served in North Africa. The big craft was completely successful as a reconnaissance platform, possessing range, stability, and ease of handling to facilitate its tasks. Not particularly fast, the Fw 189 was extremely agile and, at low altitude, could outturn most fighters with ease. Failing this, it could also absorb considerable damage, and was known to survive direct ramming attacks by Russian aircraft. By war’s end, improved Allied fighters made reconnaissance work untenable, so Fw 189s were reassigned to liaison and casualty evacuation work. A handful also flew with Hungarian and Slovakian forces for similar purposes.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 34 feet, 5 inches; length, 28 feet, 10 inches; height, 12 feet, 11 inches Weights: empty, 6,393 pounds; gross, 8,700 pounds Power plant: 1 x 1,700-horsepower BMW 801 radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 391 miles per hour; ceiling, 34,775 feet; range, 497 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns; 2 x 20mm cannons; up to 2,200 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1940-1945

|

T |

he aptly named “Butcher Bird” was one of the deadliest German fighters of World War II and, possibly, of all time. It was produced in huge numbers and became the chosen mount of many high – ranking aces.

In 1937 the German Air Ministry issued specifications for a new fighter as a hedge against the new and heretofore untried Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter. Dr. Kurt Tank of the Focke-Wulf Flugzeug – bau firm broke with tradition by conceiving a radial-engine design. This was a dicey departure from aerodynamic norms, given the Luftwaffe’s stated preferences for in-line liquid-cooled motors. Tank, however, expertly streamlined the craft with a close-fitting cowl, a spacious canopy, and wide – track landing gear. The new Fw 190 underwent test flights throughout 1939, where it demonstrated marked superiority in handling over the Bf 109 and virtually every fighter then extant. It was fast, highly maneuverable, and ruggedly built and entered production in 1940. When first encountered over the English Channel in the summer of 1941,

Fw 190s had little trouble mastering the opposing Spitfire Vs. For once, German pilots enjoyed a qualitative—if short-lived—superiority over their enemies. But the Fw 190 also proved adept as a ground-attack craft and a dive-bomber. By 1944 they had almost completely displaced the previously vaunted Stuka in those roles.

Because the Fw 190’s performance faltered at high altitude, in 1943 Tank began development of a radically different version. The new Fw 190D was powered by a liquid-cooled in-line engine, although its annular radiator preserved the radial appearance of the series. The fuselage was also lengthened and heavier armament fitted. “Long-nose Dora,” as it was called, became the best German fighter of the war, easily capable of tangling on equal terms with P-51D Mustangs and late-model Spitfires. An even better high-altitude version, christened the Ta 152, exhibited superb performance, but only a handful were constructed, and none saw combat. By war’s end, no less than 20,087 Fw 190s were constructed in various models.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 107 feet, 9 inches; length, 76 feet, 11 inches; height, 20 feet, 8 inches

Weights: empty, 37,478 pounds; gross, 50,044 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 1,000-horsepower BMW 323R-2 radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 224 miles per hour; ceiling, 19,685 feet; range, 2,211 miles Armament: 4 x 13mm machine guns; 1 x 20mm cannon; up to 4,630 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1940-1945

|

L |

umbering Condors were so adept at sinking ships that Winston Churchill dubbed them the “scourge of the Atlantic.” Their success is even more remarkable considering that they were commercial aircraft adopted for military purposes.

In 1936 Deutsche Lufthansa requested designs for a 26-passenger airliner capable of nonstop service between Berlin and New York. Dr. Kurt Tank complied in 1937 with his beautiful Fw 200, an allmetal, low-wing monoplane with double wheels that retracted into streamlined nacelles. That year the Fw 200 established many world records for distance, including a 48-hour flight to Tokyo. The Japanese were so impressed that they requested a maritime reconnaissance version to be developed for their military. The onset of World War II in 1939 forestalled any such development, and various prototype and commercial Fw 200s were hastily impressed into service as transports. In this capacity they achieved only limited success as, being non – stressed for military service, they proved structurally weak. In fact, they acquired a bad reputation

for breaking their backs after a hard landing. But by 1940 the Fw 200 found its niche as a long-range antishipping bomber.

The Fw 200 Condor frequently operated in close cooperation with roving packs of U-boats. These machines had been refitted with a long ventral gondola beneath the fuselage, where bombs were housed. Having identified an enemy convoy, Condors would attack and cripple merchant vessels, leaving the submarines to finish them off. Within a year Fw 200s accounted for several thousand tons of Allied shipping and were justly feared as the “scourge of the Atlantic.” Eventually, the development of long-range fighters like the Bristol Beaufighter and ship-launched disposable Hawker Hurricanes spelled the end of its maritime roles. The Fw 200s next pioneered antishipping missiles, but success proved elusive, and by 1944 most had been reconverted back into transports. Significantly, both Adolf Hitler and Heinrich Himmler used Condors as their personal transports. A total of 276 were constructed.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 41 feet; length, 31 feet, 2 inches; height, 11 feet, 5 inches Weights: empty, 2,756 pounds; gross, 4,079 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 336-horsepower Hispano-Suiza liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 140 miles per hour; ceiling, 18,045 feet; range, 478 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns; up to 441 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1924-1940

|

T |

he Fokker C V was one of the most popular and widely exported aircraft of the interwar period. It could be fitted with a wide variety of engines or wingspans depending upon its intended use.

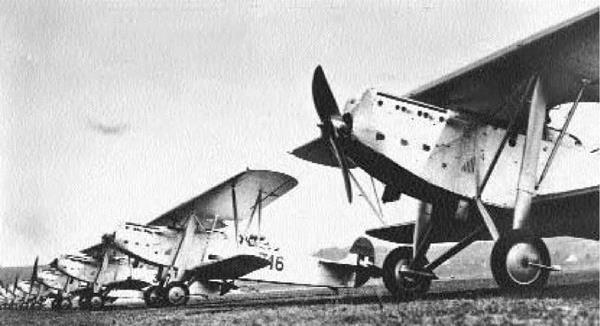

In 1924 Anthony Fokker’s genius for innovation was never more evident than in his C V aircraft. Outwardly, it was a conventional biplane with unequal wings, fixed landing gear, and a highly streamlined nose. The fuselage was constructed of steel tubing and fabric-covered throughout, while the wings employed wood in their construction. It flew exceptionally well, was fast for its day, and, in the tradition of Fokker airplanes, proved exceptionally rugged. The C V was marketed to the Dutch military as a light bomber, but Fokker had in mind a multipurpose aircraft. He accomplished this by enabling the C V to be fitted with differing sets of wing shapes and spans according to the mission desired, and all could be interchanged in under an hour. Engines were also easily replaced for the same purpose. The C V en

tered the Dutch air force in 1924 and was immediately popular with both flight and ground crews. For almost a decade and a half it reigned as the most successful aircraft of its class. Fokker constructed more than 400 machines, which proved so well built that few ever returned for reconditioning. He later complained that this happy predicament led to acute work shortages at his factory!

The high performance, reliability, and supreme flexibility of the C V made it ideal for export purposes, and it was acquired by Bolivia, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, Italy, Hungary, and Switzerland. Once manufacturing licenses were granted, total production of C Vs worldwide exceeded 1,000 machines. The most popular variants proved the C V-D and C V-E, which functioned as fighters and light bombers, respectively. In 1928 it was a Swedish C V skiplane that rescued Admiral Umberto Nobile when his airship crashed in the Arctic. Several Dutch machines were still in service and actively flown during the German invasion of 1940.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 29 feet, 2 inches; length, 22 feet, 9 inches; height, 9 feet

Weights: empty, 1,477 pounds; gross, 1,984 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 185-horsepower BMW IIIa liquid-cooled in-line engine

Performance: maximum speed, 117 miles per hour; ceiling, 19,685 feet; range, 200 miles

Armament: 2 x 7.62mm machine guns

Service dates: 1918-1926

|

T |

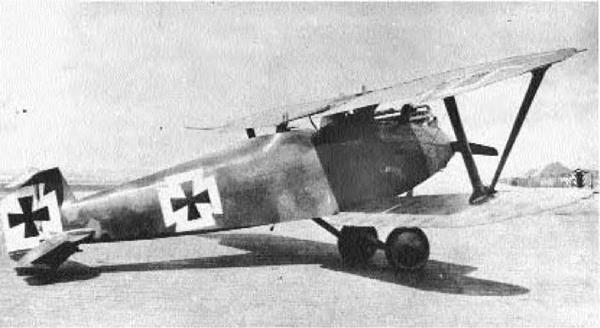

he legendary Fokker D VII was one of history’s greatest fighter aircraft. Its reputation was so formidable that the 1918 Armistice terms specifically authorized confiscation of all D VIIs by Allied forces.

By December 1917 the German High Command witnessed control of the air slipping irrevocably back into Allied hands. The following January they announced competition for a new fighter craft to employ the excellent Mercedes D III engine. No less than 60 prototypes appeared at Aldershof as planned, but events were dominated by a machine entered by Anthony Fokker. His D VII model, designed by Reinhold Platz, was a conventional biplane of exceptionally graceful lines. Its wings were constructed from wood, and the fuselage consisted of a tube steel structure covered by fabric. But first and foremost, the D VII was extremely maneuverable, especially at high altitudes. With such striking performance, it was decided to rush Fokker’s invention immediately into production without further delay. An estimated 1,000 were constructed by Fokker, in concert with Albatros and AEG.

The first Fokker D VIIs appeared over the front in the spring of 1918 and were an unpleasant surprise to Allied pilots. Although slower than many adversaries, D VIIs could outturn and outclimb a host of excellent airplanes, including the SE 5a, Sopwith Camel, and SPAD XIII. Moreover, it had a remarkable ability to briefly “hang” on its propeller, firing upward. Allied casualties soared correspondingly, and it looked like the formidable Fokker might single-handedly regain control of the skies for Germany. The war ended in November 1918 before that transpired, but the Allies acknowledged the D VII’s formidable reputation with a direct compliment. They demanded outright confiscation of all surviving D VII’s as part of the Armistice conditions!

No sooner had hostilities ceased than Anthony Fokker smuggled about 160 D VIIs over the border into neutral Holland, where he sold them to the Dutch air force. These fine aircraft were subsequently exported globally and remained in the Belgian service until 1926. The D VII was a classic fighter design.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 27 feet, 6 inches; length, 19 feet, 3 inches; height, 9 feet, 3 inches

Weights: empty, 848 pounds; gross, 1,238 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 110-horsepower Oberursel UR II rotary engine

Performance: maximum speed, 115 miles per hour; ceiling, 20,669 feet; range, 150 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns Service dates: 1918

|

T |

he “Flying Razor” was the last and among the finest German fighters to appear in World War I. Had fighting continued into 1919, it would have ultimately replaced the already formidable Fokker D VII.

In the spring of 1918, the German High Command authorized a second fighter flyoff at Aldershof. Among the many prototypes represented was a new monoplane designed by Reinhold Platz, the Fokker V 26/28. From an appearance standpoint, it possessed a steel-tube and fabric-covered fuselage, a cowling borrowed from the Dr I triplane, and the tail section of the D VII. The single wing was made from wood and possessed a thick chord with tapering tips, and numerous struts secured it to the fuselage. This parasol machine represented the last German application of rotary-engine technology since the obsolete Eindekker of 1915. More important, it was fast and extremely agile, and for a second time the Fokker design totally dominated the competition. Consequently, it was decided to rush the new craft immediately into production as the Fokker E V. An

estimated 400 of these machines, subsequently redesignated D VIIIs, were constructed over the intervening months.

The first batches of D VIIIs reached the front in April 1918 for further evaluation. Pilots marveled at the new fighter’s climb and maneuverability, but when three were lost to unexplained crashes, the program was suspended. Investigations revealed that poor workmanship and imperfect timber were the cause, which were corrected, but much valuable time had been lost. It was not until September 1918 that production could resume. The first combat – ready D VIII’s arrived at the front in late October, just three weeks prior to the end of the war. Nevertheless, they fully upheld the formidable reputation acquired by the famous Fokker D VIIs and were flown with considerable success. In one skirmish on November 6, 1918, Flying Razors claimed three SPAD XIIIs in a matter of minutes. The war concluded in November before the D VIIIs had a chance for further distinction, but they were the last combat aircraft fielded by Imperial Germany.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 36 feet, 1 inch; length, 26 feet, 10 inches; height, 9 feet, 8 inches

Weights: empty, 3,197 pounds; gross, 4,519 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 830-horsepower Bristol Mercury VIII radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 286 miles per hour; ceiling, 36,090 feet; range, 590 miles

Armament: 4 x 7.92mm machine guns

Service dates: 1938-1944

|

T |

he Fokker D XXI saw widespread service in three European air forces before and during World War

II. It marked a transitional stage between fabric-covered biplanes and stress-skinned monoplanes.

The Fokker D XXI evolved in response to a 1935 specification laid out by the Netherlands East Indies Army Air Service, which sought a new monoplane fighter to replace the antiquated biplanes then employed. Fokker, which enjoyed a tremendous international reputation for effective and innovative designs, responded with a rather conservative machine, but it was well-suited to simplicity and ease of operation. The Fokker D XXI first flew in 1938 as a low-wing monoplane with fixed, spatted undercarriage. True to company tradition, it consisted of steel tubing and wooden wings and was covered by fabric. The only modern aspect was the fully enclosed cockpit. Test flights revealed the craft to be underpowered but also responsive and highly maneuverable. During one flight an altitude of 37,250 feet was reached—a Dutch record. In 1938 the Dutch air force obtained 36 examples. These were

followed by two imported by Denmark, which constructed another 10 under license, and 40 for Finland. The Republican government in Spain also expressed interest in the D XXI as its standard fighter, but Nationalist forces overran the factory intended to produce them. Worse still, the D XXI was verging on obsolescence when World War II broke out in September 1939.

Dutch Fokkers enjoyed a brief but useful wartime career. On May 10, 1940, they intercepted a formation of 55 Junkers Ju 52 transports, shooting down 37 with heavy loss of life. Several Me 109s were also claimed before ammunition stocks were exhausted and the planes grounded. Denmark, which had been experimenting with a 20mm cannon-armed version, offered no resistance, and its D XXIs were confiscated by Germany. However, Finland put the fighter to excellent use during the 1939 Soviet invasion, and D XXIs scored the first aerial kill of that conflict. When war resumed in 1941, Finland constructed an additional 50 D XXIs and flew them with great effect until 1944.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 23 feet, 7 inches; length, 18 feet, 11 inches; height, 9 feet, 8 inches

Weights: empty, 904 pounds; gross, 1,289 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 110-horsepower Oberursel rotary engine

Performance: maximum speed, 103 miles per hour; ceiling, 20,013 feet; range, 150 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns Service dates: 1917-1918

|

T |

he career of the famous triplane is indelibly linked to that of Manfred von Richthofen, the infamous “Red Baron.” In his hands the diminutive Fokker was a deadly weapon whose reputation long survived his passing.

German authorities were shocked by the appearance of the Sopwith Triplane in the spring of 1917, which induced them to develop aircraft of similar design. A total of 14 different machines were eventually constructed and flown, but the most effective proved Fokker’s Dr I Dreidecker, designed by Reinhold Platz. The resulting prototype was compact and initially lacked interplane struts. The surface area of three wings afforded it marvelous powers of maneuver and climb. The middle section vibrated excessively in a dive, however, so struts were subsequently added between them. Several preproduction craft were then dispatched to be evaluated under combat conditions. One of them was flown by leading ace Werner Voss, who scored 20 victories in only 24 days. In fact, the Dr I was a dangerous weapon in the hands of experienced pilots—

and equally dangerous and unforgiving for the novice. Nonetheless, in the summer of 1917 Fokker commenced full-scale production of the Dr I, which terminated at 320 machines.

One of the earliest Jadgeschwaders (fighter groups) to receive the diminutive craft was the famous “Flying Circus” of Manfred von Richthofen. The Red Baron excelled in flying the Fokker Dr I, and increased his already impressive tally to 80 kills before he himself was killed in action on April 21,

1918. The other leading Dreidecker ace, Voss, met his demise earlier, on September 23, 1917, when he dramatically and single-handedly dueled an entire patrol of British SE 5s. Despite uniform success in combat, several unexplained crashes were attributed to structural weaknesses. The Dr I was consequently grounded for several months pending repairs and did not return to combat until late 1917. Thereafter newer allied aircraft minimized its effectiveness, and by the spring of 1918 the heyday of the triplane had passed. The Dr I was superceded by Fokker’s other superb design, the D VII.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 31 feet, 4 inches; length, 23 feet, 7 inches; height, 9 feet, 2 inches

Weights: empty, 878 pounds; gross, 1,342 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 100-horsepower Oberursel U. I rotary engine

Performance: maximum speed, 81 miles per hour; ceiling, 11,500 feet; range, 100 miles Armament: 1 x 7.92mm machine gun Service dates: 1915-1916

|

I |

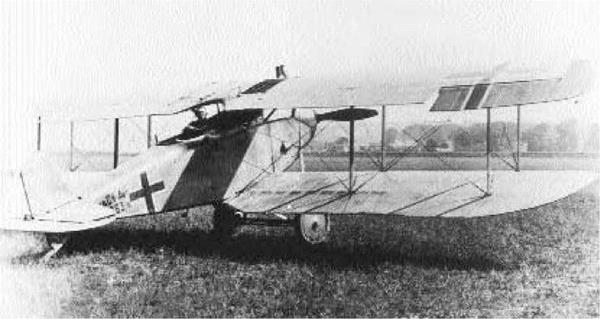

n the autumn of 1915, the anachronistic-looking Eindekker reigned as the world’s best fighter aircraft. Its superiority over contemporary French and English machines ushered in a period known as the “Fokker scourge”—and the dawn of modern aerial warfare.

April 19, 1915, signified a turning point in the history of military aviation when the French-built Morane-Saulnier L aircraft piloted by Roland Garros crashed behind German lines. German investigators combing through the wreckage discovered that Garros had clandestinely mounted a machine gun fixed so as to fire through the propeller arc. The propeller itself was fitted with metal wedges to deflect any unsynchronized projectiles, but the Germans recognized the advantages an improved system would bring. The brilliant aircraft designer Anthony Fokker was contacted, whose firm was familiar with the concept, and within two weeks a completely synchronized interrupter gear was devised. This allowed bullets to shoot through a moving propeller by being deliberately timed to miss it. This technol

ogy was then grafted onto a Fokker M 5 monoplane, a design that had been flying since 1913, for trials. Thus was born the Fokker E I, the world’s first true fighter craft. A total of 400 of all models were built, and their tactical implication was immense.

At a time when Allied craft were either unarmed or simply carried rifles and other sidearms for defense, the new Fokker Eindekkers represented a quantum leap in firepower. Throughout the fall and winter of 1915, they sawed through nearly 1,000 allied reconnaissance craft, chiefly lumbering British Be 2cs. The Fokkers also stimulated the evolution of new fighter tactics as pioneered by Germans aces like Max Immelmann and Oswald Boelcke. For several months the “Fokker scourge” dominated the skies of Western Europe until the spring of 1916, when superior fighters like the Nieuport 11 Bebe and the de Havilland DH 2 pusher debuted. The days of the ugly, ungainly Eindekkers were numbered in weeks, but a corner had been turned. Hereafter, warplanes ceased being frail-looking contraptions and evolved into machines of increasing deadliness.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 56 feet, 3 inches; length, 37 feet, 9 inches; height, 11 feet, 2 inches

Weights: empty, 7,410 pounds; gross, 10,582 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 830-horsepower Bristol Mercury VIII radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 295 miles per hour; ceiling, 30,500 feet; range, 870 miles

Armament: 9 x 7.92mm machine guns; up to 882 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1938-1940

|

T |

he hulking G I was the Netherlands’s most combat-capable aircraft of World War II. Despite great potential, nearly all were destroyed after heroic and futile resistance.

In 1935 Fokker initiated a company-funded project to produce a large interceptor that could also double as a ground-attack craft. Christened the G I, it was secretly developed and not publicly unveiled until the 1936 Paris Salon. The G I was unlike any aircraft previously seen and generated considerable interest. It was a twin-boomed craft with pilot, crew, and armament housed in a large central nacelle. The two booms mounted Hispano – Suiza radial engines and were joined aft of the fuselage by a single stabilizer. Construction was mixed, consisting of steel tubing and fabric covering. But the most significant feature was the armament: no less than eight 7.92mm machine guns were concentrated in the nose while the tailgunner operated a single weapon. The G I first flew in March 1937 to the satisfaction of company officials, and it was

next offered to the Luchtvaartafdeling (army air service). An order for 36 machines resulted, with initial deliveries arriving the following year. In the quest for engine standardization, however, the army required that the more common Bristol Mercury radial engine be mounted. At the time of its appearance, the G I was probably the most advanced warplane of its kind in the world. It seemed so promising that orders from Sweden, Spain, and Denmark were also forthcoming. Given its formidable armament, the G I was unofficially dubbed the Faucheur (Mower).

When Germany attacked the Netherlands in May 1940, only 23 G Is had been deployed, and these were assigned to the 3rd and 4th Fighter Groups of the 1st Air Regiment. Several were caught on the ground and destroyed during the initial onslaught, but a handful continued fighting over the next several days. All were destroyed save one. The Germans then confiscated several G Is still on the assembly line for completion and use as trainers.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber; Trainer

Dimensions: wingspan, 24 feet; length, 31 feet, 9 inches; height, 9 feet, 7 inches Weights: empty, 5,140 pounds; gross, 8,630 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 4,230-pound thrust Hawker-Siddeley Orpheus turbojet engine Performance: maximum speed, 636 miles per hour; ceiling, 48,000 feet; range, 1,151 miles Armament: none Service dates: 1962-1979

|

T |

he lively little Gnats would have made excellent low-cost fighters, but the Royal Air Force preferred them as trainers instead. For many years they thrilled thousands as part of the Red Arrows precision acrobatic team.

The rising costs inherent to modern jet technology persuaded W. E.W. Petter to develop a new lightweight fighter. By 1955 this had become practical with the advent of smaller, more powerful jet engines, and the concept was pursued as a company – funded venture. That year Folland unveiled the Midge, a high-performance aircraft that was a foot shorter and 1,000 pounds lighter than the Messer – schmitt Me 109! This was a high-wing monoplane with highly swept wings and control surfaces. The RAF, however, expressed no interest in the Midge as a combat aircraft, and they entreated Petter to develop a similar craft for training purposes. The prototype flew in 1956 and was similar to the Midge, save for an extended nose to house an additional pilot and broader wings to slow down landing speeds. The RAF was impressed by the little craft

and authorized a preproduction batch of six machines. By 1965 it had acquired no less than 105 Gnats for their inventory.

The Gnat was destined to replaced the Vampire T.11 as an advanced jet trainer and be the next instructional step after the slower Hunting Jet Provost. In service it possessed all the flight characteristics of modern jet fighters and could break the sound barrier in a shallow dive. Gnats also proved overly complex and difficult to maintain, but they nonetheless rendered useful service for nearly two decades before being replaced by BAe Hawks. They also performed useful recruiting service in the thrilling exhibitions by the famous Red Arrow acrobatic team. The Gnat also received friendly reception from Finland and India. The former bought a handful rigged as fighters and operated them as such until 1972. India, meanwhile, manufactured several hundred under license as the HAL Ajeet. In numerous wars with Pakistan they proved to be agile targets and difficult to hit. Many Gnats remain operational to this day.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 77 feet, 11 inches; length, 42 feet, 1 inch; height, 12 feet Weights: empty, 5,929 pounds; gross, 8,646 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 260-horsepower Mercedes D IVa liquid-cooled in-line engines Performance: maximum speed, 87 miles per hour; ceiling, 14,764 feet; range, 400 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns; 1,102 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1916-1918

|

T |

he Friedrichshafen G III was a capable German heavy bomber that combined good range with respectable bomb loads. In concert with the Gotha V, it ranged across the Western Front and inflicted considerable damage.

The firm Flugzeugbau Friedrichshafen had been founded by the famous Count Ferdinand Zeppelin prior to World War I and was best known for producing naval seaplanes. In 1914 chief engineer Theodor Kober began designing the company’s first heavy bomber for the land service. The G I emerged in 1915 as a twin-engine, three-bay biplane of pusher configuration. It failed to go into production, and the following year a second variant, the G II, was constructed. This was a two-bay pusher design whose wings contained steel center-section spars for added strength. It also carried a pilot and two gunners who sat in the fore and aft positions. The G II was deployed in 1916, but because of limited range and payload it served only in small numbers.

The final Friedrichshafen bomber of the war was the G III. Like the earlier G I, it was a three-bay

biplane pusher whose lengthy wings also sported double ailerons. The fuselage was constructed of wood, covered by fabric, and unique in that the central section served as an integral unit housing the crew, fuel, engines, and bombs. The landing gear were large, set in pairs, and also contained a large nosewheel to prevent overturning on rough terrain. The final product functioned well and entered production in 1917. Precise figures are not known, but at least 330 machines were assembled by various contractors.

In service the G III flew mostly from bases in Northwestern Europe and conducted long-range bombing raids against British positions at Dunkirk, along with several nighttime raids against Paris. There is, however, no proof that they raided England alongside the more famous Gotha Vs. In 1918 a final version, the G IV, was deployed, which differed from earlier variants in being snub-nosed and having engines mounted in tractor configuration. All were tough, reliable machines.

Type: Glider; Transport

Dimensions: wingspan, 110 feet; length, 68 feet; height, 20 feet, 3 inches Weights: empty, 18,400 pounds; gross, 36,000 pounds Power plant: none

Performance: maximum speed, 150 miles per hour Armament: none Service dates: 1944-1945

|

T |

he giant Hamilcar was the largest transport glider employed by Allied forces in World War II. It was the first such craft to convey tanks and other armored vehicles directly into combat.

The development of airborne forces by 1940 gave armies unprecedented mobility and tactical surprise. Now it was possible to insert military power at any point on a map. However, paratroopers remained essentially light infantry because all their requisite supplies were carried on their backs. They were thus at a disadvantage when fighting well-armed ground forces possessing greater firepower and ammunition. The British Air Ministry contemplated this fact in 1940 when it undertook development of airborne forces in the wake of Germany’s dazzling successes in Belgium. It also issued Specification X.27/40, calling for creation of a large glider craft capable of hoisting small tanks, trucks, or artillery pieces to assist parachutists wherever they landed.

In March 1942 General Aircraft responded with a glider transport called the Hamilcar, a huge and rather sophisticated craft. This was a high – wing monoplane of all-wood construction flown by

a crew of two. The canopy was placed on top of the fuselage just forward of the wing’s leading edge and was accessed by ladder. The wing itself was fitted with pneumatically actuated slotted trailing edges and slotted ailerons to facilitate short landings. The fuselage, meanwhile, was a boxy, rectangular affair with a cavernous cargo hold measuring 25 feet by 8 feet. No less than two armored Bren – gun carriers, a 40mm Bofors gun and a tow truck, or a seven-ton Locust or Tetrarch tank, could easily be accommodated. Furthermore, the entire nose of the craft was hinged to afford ease of loading and unloading. Up to 17,600 pounds of cargo could be towed aloft by a Halifax bomber and landed safely where needed.

Hamilcars experienced their baptism of fire on June 6, 1944, when 70 of these huge planes were successfully launched over Normandy in support of Allied paratroopers. They subsequently rendered useful service at Arnhem that fall, and during the Rhine crossings in 1945. A total of 390 were manufactured, including several powered Mk X versions intended for eventual use against Japan.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 32 feet, 9 inches; length, 26 feet, 2 inches; height, 10 feet, 4 inches

Weights: empty, 2,775 pounds; gross, 3,970 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 645-horsepower Bristol Mercury radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 230 miles per hour; ceiling, 33,500 feet; range, 460 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns Service dates: 1934-1943

|

L |

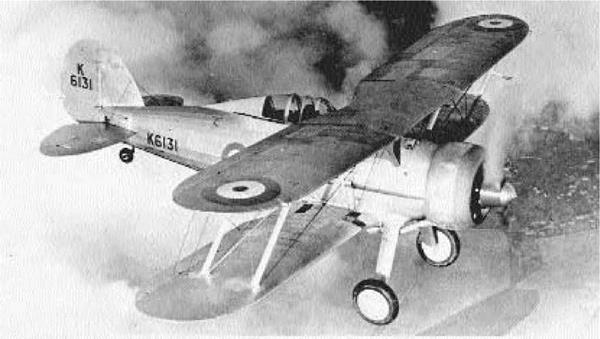

ast of the open-cockpit British biplanes, the Gauntlet was probably the world’s best fighter of its day. Fast and maneuverable, it even conducted the first-ever radio-controlled intercept.

In 1929 the unexpected performance of the Fairey Fox bomber, which could outpace any British fighter then in service, was disconcerting to the Air Ministry. Consequently, it released specifications for a new craft capable of exceeding 250 miles per hour in level flight.

In 1933 a Gloster design team under H. P. Fol – land responded with Model SS.19B, the updated version of an aircraft first flown in 1928. This machine had earlier lost out to the superb Bristol Bulldog, but the company refined it over time at its own expense. The new design was a two-bay biplane with staggered wings, and extreme attention being paid to streamlining. For example, all bracing-wire fittings were carefully sunk into the wings, leaving only the wires themselves exposed, and these, too, were specially streamlined. Moreover, all external control levers were deleted, and the bottom wing

was carefully faired into the fuselage. The fuselage itself was oval in cross-section, constructed of metal frames, and covered in fabric. The new machine was highly maneuverable and demonstrated a 40 mile – per-hour advantage over the same Bulldog that had bested it five years earlier. In 1934 it entered production as the Gauntlet I; 24 machines were purchased.

In 1935 a new version, the Gauntlet II, arrived. These differed mainly in construction techniques, as the Hawker firm had absorbed Gloster and imposed its own design philosophy. Some of these craft sported a new three-blade metal propeller in place of the standard two-blade wooden one. They were also built in relatively large numbers—204 machines—and equipped no less than 14 squadrons of RAF Fighter Command. In 1937 three Gauntlets were successfully vectored to an oncoming civilian airliner, thereby concluding history’s first radio-controlled intercept. These versatile fighters were superseded by Hawker Hurricanes and Gloster Gladiators by 1938, although some flew combat missions in East Africa as late as 1943.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 32 feet, 3 inches; length, 27 feet, 5 inches; height, 11 feet, 7 inches

Weights: empty, 3,444 pounds; gross, 4,864 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 830-horsepower Bristol Mercury IX radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 257 miles per hour; ceiling, 33,500 feet; range, 440 miles

Armament: 4 x.303-inch machine guns

|

|

Service dates: 1937-1944

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 52 feet; length, 56 feet, 9 inches; height, 16 feet Weights: empty, 38,100; gross, 43,165 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 12,300-pound thrust Armstrong/Siddeley Sapphire turbojet engines Performance: maximum speed, 702 miles per hour; ceiling, 52,000 feet; range, 930 miles Armament: 4 x 30mm cannons; 4 x Firestreak missiles Service dates: 1956-1968

|

T |

he mighty Javelin was the world’s first twin-jet delta fighter and also the Royal Air Force’s first all-weather interceptor. Mounting numerous radars and computer systems, it operated at day and night under any weather conditions.

Technological strides made during World War II badly blurred the distinction between daytime and nighttime fighters. By 1945 the state of bombardment aviation allowed such craft to perform military missions in any kind of weather or time of day. Clearly, new all-weather fighters, equipped with radar to peer through the overcast, were becoming necessary to intercept them. In 1948 the British Air Ministry proclaimed Specification F.4/48 to obtain a swept-wing jet-powered interceptor. The new machine was required to operate at great heights under all meteorological conditions and in the dark. A Gloster design team under Richard W. Walker then submitted plans for the world’s first twin-engine delta fighter. After lengthy gestation, the prototype emerged in November 1951 with a spectacular appearance. The Gloster craft was a 138 _ large delta configuration, with its twin engines

buried in the flattened fuselage. A crew of two sat in a teardrop canopy behind an extremely pointed nose housing a large radar system. Delta wings promised good performance at high speeds and high altitudes, but they were inherently dangerous to land owing to the high angle of attack on approach (that is, it approached the runway with its nose in the air). Because this was impractical for nighttime and poor-weather operations, the new craft was consequently fitted with a high “T” tail to allow landing at safer angles. After additional testing, the machine finally became operational in 1956 as the Javelin. It was England’s first attempt at building a modern all-weather fighter.

During the next decade the Javelin passed through seven distinct models, each offering successive improvements in performance and capability. The most significant of these was the FAW.7, which deleted cannon armament in favor of Firestreak missiles for the first time. A total of 428 Javelins were built, equipping no less than 14 squadrons. Excellent craft all, they were finally mustered out by 1968 after a distinguished service career.

Type: Fighter; Night Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 37 feet, 2 inches; length, 44 feet, 7 inches; height, 13 feet Weights: empty, 8,140 pounds; gross, 15,700 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 3,500-pound thrust Rolls-Royce Derwent 8 turbojet engines Performance: maximum speed, 598 miles per hour; ceiling, 43,000 feet; range, 980 miles Armament: 4 x 20mm cannon Service dates: 1944-1957

|

T |

he Meteor was the first jet operated by the Royal Air Force and the only Allied jet to see action during World War II. It proved surprisingly adaptable and spawned several postwar variants.

By 1940 the nascent technology of jet propulsion seemed promising, so the British Air Ministry issued Specification F.9/40, calling for the creation of a functioning jet fighter. Gloster, which had designed and operated the G.40, Britain’s first jet, was selected for the task. A design team under George Carter constructed a prototype that first flew in March 1943. This craft, the Meteor, was a twin-engine machine with straight wings, a bubble canopy, and tricycle landing gear. Two engines were chosen over one due to the relatively weak thrust of British engines at that time. The plane was otherwise conventionally constructed of sheeted metal skin and flew surprising well. The first Meteors became operational in July 1944, only weeks after the German Messerschmitt Me 262 had debuted, and commenced downing V-1 rocket bombs. Several improved Mk Ills, with Rolls-

Royce Derwent engines, were also committed to Europe during the last weeks of the war, performing ground-attack missions. Afterward better engines became available, and in 1946 Meteors established two absolute speed records of 606 and 616 miles per hour respectively.

The Meteor’s basic design was sound and rather adaptable, which gave rise to several versions throughout the postwar era. These included two – seat trainer, photo-reconnaissance, and night-fighting variants. The most numerous fighter, the Mk 8, flew in 1947 and constituted the bulk of RAF jet strength through the early 1950s. Several fought in the Korean War with Australian forces, although they were outclassed by Russia’s more modern MiG 15s. The most important night fighter, the NF 11, was built by Armstrong-Whitworth in 1950. This craft employed two crew members and a totally redesigned and lengthened nose section. Meteors of every stripe served with impressive longevity and rendered excellent service with the RAF and other air forces up through the late 1950s.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 77 feet, 10 inches; length, 40 feet; height, 12 feet, 8 inches Weights: empty, 6,041 pounds; gross, 8,763 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 260-horsepower Mercedes D IVa liquid-cooled in-line engines Performance: maximum speed, 87 miles per hour; ceiling, 21,325 feet; range, 311 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns; up to 1,061 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1917-1918

|

T |

he mighty Gotha symbolized German strategic bombing in World War I. Their attacks on London did relatively little damage but great psychological harm and were harbingers of what would transpire two decades later.

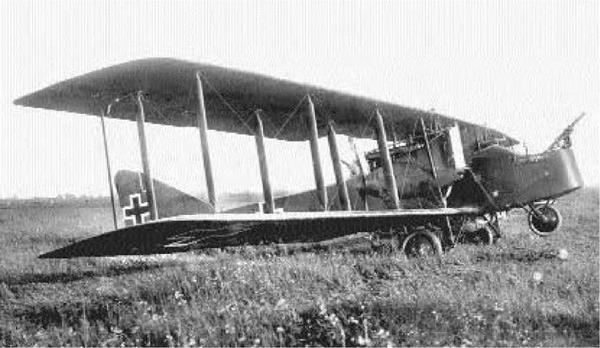

By 1916 Zeppelin attacks on England could not be mounted without intolerable losses to those giant lighter-than-air craft. The German High Command thereupon announced specifications for a Gross- flugzeug (large bomber) capable of hitting these same targets. It so happened that the firm Gothaer Waggonfabrik had been experimenting with a series of large aircraft for such purposes. The first three models, G I through G III, were variations on a basic theme and suffered from inadequate range and bomb loads. The first production version, the G IV, proved an entirely different matter. This was a large, three – bay, twin-engine aircraft, with propellers mounted in pusher configuration. A crew of three was required, consisting of a pilot and two gunners. Made entirely of wood and fabric-covered, the G IVs were some

what fatiguing to fly, owing to a poorly located center of gravity, and were also prone to damage if roughly landed. About 230 Gotha G IVs were acquired in 1917.

The first daylight Gotha raid against England occurred on May 25, 1915, when the city of Folkestone suffered 95 casualties. This was followed by a major attack against London on June 13, 1917, whereby 162 people were killed and 432 injured. From a strategic standpoint these raids were mere pinpricks, but public outrage necessitated redeploying several fighter squadrons from France for home defense. When the Gothas began taking losses, they switched to night attacks after August 1917. The British initially experienced difficulty coping with such tactics, but by dint of searchlights and pluck they managed to bring down several more bombers. Consequently, Gotha night raids were suspended after May 1918. A more powerful model, the G V, was in service by then, and surviving Gothas restricted their activities to bombing targets on the continent.

Type: Glider

Dimensions: wingspan, 80 feet, 4 inches; length, 51 feet, 10 inches; height, 15 feet, 5 inches Weights: empty, 11,243 pounds; gross, 17,196 pounds

Power plant: none or 2 x 700-horsepower Gnome-Rhone 14M radial engines Performance: maximum speed, 180 miles per hour; ceiling, 24,605 feet; range, 373 miles Armament: 4 x 7.92mm machine guns Service dates: 1942-1944

|

T |

he Go 242 was the most widely used German glider during the letter half of World War II. It saw active use in the Mediterranean and Russian theaters, and a powered version also became available.

In 1941 the startling success of the DFS 230 assault glider prompted the German Air Ministry to request larger, more capable craft. It devolved upon Albert Kalkert of the Gothaer Waggonfabrik firm to design a radical solution to the problem of bigger gliders. His Go 242 was unique in being a highwinged craft with three times the troop-carrying capacity as the DFS 230. Constructed of metal framework, wood, and fabric, the Go 242 consisted of a large fuselage pod with a hinged rear section to permit ease of entry and exit. It was centered between twin booms joined together by a single tailplane and twin rudders. While being towed for takeoff, the Go 242 would drop a jettisonable wheeled dolly and land on a semiretractable noseskid and fixed rear wheels. Jeep-type vehicles could easily be accommodated in its capacious fuselage. German authori

ties were highly pleased with the prototype, so in 1941 they authorized immediate production. A total of 1,528 were constructed.

The Go 242 became operational in the spring of 1941 and was initially deployed in the Aegean and Mediterranean theaters. However, they were used heavily along the Russian front and specialized in bringing supplies and reinforcements to isolated German detachments. An amphibious version, the Go 242C, was specially developed for an attack upon the British battle fleet at Scapa Flow. This craft possessed a watertight hull with flotation bags and carried small powered assault boats. Once landed, the boats would disgorge, move alongside a moored warship, and attach a 2,600-pound charge to the hull. This intriguing plan never materialized owing to a lack of aviation fuel. The final version was the Go 244, unique in being powered by captured Gnome-Rhone radial engines. A total of 144 machines were converted to this standard but, slow and vulnerable, were withdrawn from combat and assigned training duties.

Type: Reconnaissance

Dimensions: 44 feet, 8 inches; length, 22 feet, 8 inches; height, 11 feet

Weights: empty, 2,046 pounds; gross, 2,730 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 220-horsepower Benz Bx. IV liquid-cooled in-line engine

Performance: maximum speed, 106 miles per hour; ceiling, 16,405 feet; range, 350 miles

Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns

Service dates: 1918

|

T |

he Halberstadt C V was among the last reconnaissance aircraft acquired by Germany during World War I. It possessed excellent high-altitude performance and performed doggedly until the end of hostilities.

In 1916 the firm Halberstadter Flugzeugwerke manufactured its first two-seat aircraft, the C I, which was rotary-powered and failed to enter production. However, the firm enjoyed greater success the following year by introducing the C III, designed by Karl Theiss, as a Fernerkunder (long-range reconnaissance craft). It possessed the familiar traits of most Halberstadt machines: sleek lines, rounded, almost elliptical tail surfaces, and a fuselage short in relation to the wingspan. The lower wings were also somewhat unique in being attached to a large keel along the fuselage bottom. A 200-horsepower Benz Bz. IV engine provided adequate power and respectable speed, and the C III was successfully employed for many months. By the spring of 1918, the onset of faster Allied fighters prompted the company to develop a more powerful, aerodynamically refined version.

The C V was a new craft that appeared very much in the mold of Halberstadt two-seaters. For better performance at high altitude there were high – aspect wings of considerable length, as well as a proportionally longer fuselage. It also differed from the C II in discarding the large communal cockpit in favor of separate seats for pilot and gunner. The craft utilized a stronger, higher-compression version of the Benz Bz. IV motor, developing 220-horsepower. Consequently, the C V displayed even better high-altitude performance than its lighter forebear, an essential defensive trait in the waning days of the war.

This final Halberstadt aircraft reached forward units in late summer. Its arrival coincided with the final overland drive by Allied forces, and the aircraft was constantly employed in photography to keep headquarters abreast of the latest enemy movements. Throughout a rather brief service life, the C V upheld the Halberstadt tradition for excellent and reliable two-seaters. After the war many of them ended up in the Swiss air force as trainers.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 35 feet, 4 inches; length, 24 feet; height, 9 feet Weights: empty, 1,701 pounds; gross, 2,493 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 160-horsepower Mercedes D III liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 103 miles per hour; ceiling, 16,730 feet; range, 300 miles Armament: 3 x 7.92mm machine guns; up to 100 pounds of bombs or grenades Service dates: 1917-1918

|

T |

he Halberstadt CLs were the first machine constructed for the new Germany category of multipurpose aircraft. Although intended as an escort fighter, they found their niche as a ground-attack plane.

By 1917 the expanding size of C-series reconnaissance aircraft rendered them more vulnerable to enemy aircraft, so a new category—CL (for “light C”)—was adopted. These two-seaters were intended to act as speedy, lightweight escort fighters for the slower C class and to fulfill reconnaissance duties if necessary. The first aircraft so designated was the Halberstadt CL II, an equal-span, two-bay biplane of exceptionally streamlined design. It was conventionally constructed from wood and fabric but differed from most German two-seaters by having a communal cockpit housing both pilot and gunner. The CL II was powered by the excellent 160-horsepower Mercedes D III engine, and the resulting craft was both fast and maneuverable.

The CL II saw its baptism of fire in the summer of 1917 and rendered useful service in its appointed

role. However, the craft also demonstrated suitability for the more dangerous business of ground attack, which entailed flying over enemy trenches at low altitude, strafing positions, and lobbing small bomblets. The CL II’s fast speed, robust construction, and relatively compact size rendered it difficult to shoot down, despite the fact it was totally unarmored. CL IIs distinguished themselves in fighting around Cambrai and greatly assisted the successful German counterattack of November 30, 1917. These handsome machines remained in service until the end of the war.

At length it was decided to introduce an improved version of the CL II, the CL IV. This new craft sported similar lines to its predecessor but was three feet shorter, had repositioned wings closer to the fuselage, and sported totally redesigned tail surfaces. Consequently, it possessed even greater agility at low altitudes and admirably fulfilled its escort and attack missions. Eventually both types were culled into special formations called Schlact – staffeln (battle flights) that specialized in close-support missions.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 28 feet, 10 inches; length, 23 feet, 11 inches; height, 8 feet, 9 inches Weights: empty, 1,234 pounds; gross, 1,696 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 120-horsepower Mercedes D II liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 90 miles per hour; ceiling, 13,000 feet; range, 155 miles Armament: 1 x 7.92mm machine guns Service dates: 1916-1917

|

T |

he distinctive Halberstadt D II was Germany’s first biplane fighter and the first equipped with a synchronized machine gun. An interim design at best, it fought well for several months before transferring to secondary theaters.

By the end of 1915, the balance of aerial power above the Western Front had shifted to the Allies due to the appearance of de Havilland’s DH 2 pusher fighters. These proved superior to the heretofore unstoppable Fokker EIII monoplanes and sent the Germans scrambling for superior designs of their own. By the spring of 1916 a design team under Karl Theiss began lightening and modifying a Halberstadt B II two-seater into a single-seat biplane fighter— Germany’s first. The new D II was quite unlike any previous fighter to appear thus far. It possessed an extremely tapered fuselage made of wood and metal tubing. The two bay wings were highly staggered and nearly oblong in shape, with straight trailing edges. But the craft’s most distinctive feature was the tail unit: The rudder was triangular, the horizontal stabi

lizers square. Moreover, neither of these control surfaces was directly affixed to the fuselage; instead, they were joined together by tubing and braced for greater strength. The D II’s seemingly frail appearance belied its robustness and maneuverability. Although lightly armed with one machine gun, it proved more than a match for the redoubtable DH 2.

Throughout the spring of 1916, the Halberstadt D II, alongside the equally new Albatros D IIs, wrested aerial supremacy back to the Central Powers. In combat, this small scout was an agile performer and displayed an uncanny ability to survive long, steep dives. This maneuver was unthinkable for most aircraft at that time. In 1916 D IIs also became the first German fighters equipped with small rockets for balloon-busting. However, within a year the lightly armed yet nimble Halberstadts were superceded by newer Albatros scouts and Allied designs. Only 100 were built, and most spent their final year of operations over Macedonia, Palestine, and other secondary theaters.

Type: Heavy Bomber; Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 104 feet, 2 inches; length, 71 feet, 7 inches; height, 20 feet, 9 inches

Weights: empty, 39,000 pounds; gross, 68,000 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 1,800-horsepower Bristol Hercules radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 312 miles per hour; ceiling, 24,000 feet; range, 1,260 miles

Armament: 9 x.303-inch machine guns; 13,000 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1941-1952

|

T |

he Halifax was the second member of Britain’s famous trio of “heavies.” Like its famous Lancaster rival, it began as a twin-engine design and underwent extensive modifications throughout a long service life.

The Halifax originated with Air Ministry Specification B. 13/36, issued for a new twin-engine bomber to be powered by the Rolls-Royce Vulture engines. When it became apparent that better power sources were needed, Handley Page extended the wingspan of its prototype to accommodate four Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. The Halifax first flew in October 1939, and it succeeded completely for such a large craft hastily assembled. It was a midwing bomber of all-metal construction with three powered gun turrets. The Halifax was not quite the racehorse that the latter Avro Lancaster became, but it was a marked improvement over the earlier Short Stirling in terms of altitude and payload. Halifaxes commenced active operations in the spring of 1941 and soon jointly formed the backbone of England’s nighttime strategic offensive against Germany. By

1945 it had flown 75,532 sorties and dropped 255,000 tons of bombs.

In service the Halifax was nominally a heavy bomber, but it proved itself extremely adaptable to other chores. These included maritime patrol, radarmapping, and transportation duties. Halifaxes were also responsible for destroying Germany’s V-1 launching sites, dropping off agents in Central Europe, and becoming the only heavy bomber assigned duty in the Middle East. Rounding out this impressive service record was parachute-dropping and long-range reconnaissance. Moreover, it was the only airplane capable of towing the large General Aircraft Hamilcar transport glider and did so in large numbers by 1945. To upgrade overall performance, the new Mk III version featured four Bristol Hercules radial engines, extended wingspan, and a totally redesigned nose section. Several models were also fitted with large radomes on their bellies and performed the first radar-based ground-mapping missions. After the war, this useful plane remained in service with the RAF Coastal Command until 1952. A total of 6,176 were built.

Type: Medium Bomber; Torpedo-Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 69 feet, 2 inches; length, 53 feet, 7 inches; height, 14 feet, 11 inches

Weights: empty, 11,780 pounds; gross, 18,756 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 1,000-horsepower Bristol Pegasus radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 254 miles per hour; ceiling, 19,000 feet; range, 1,885 miles

Armament: 6 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 4,000 pounds of bombs or torpedoes

Service dates: 1938-1942

|

T |

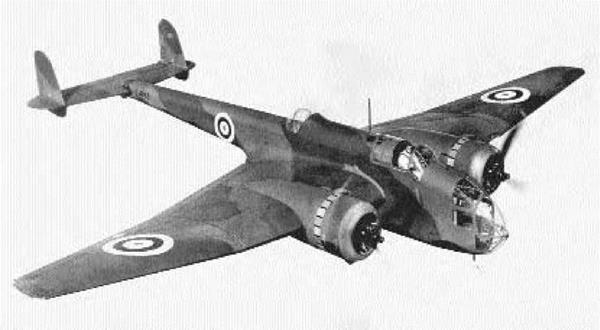

he unsung Hampden was an outstanding medium bomber during the early campaigns of World War II. Although vulnerable to fighters, it was faster and carried nearly as many bombs as competing designs.

The Hampden design arose in response to Air Ministry Specification B.9/32 for a twin-engine bomber. Both Handley Page and Vickers submitted winning designs, with the former prototype becoming the Hampden and the latter the Wellington. The Handley Page creation was one of the most unique looking bombers ever flown. It possessed a deep forward fuselage joined to an extremely narrow aft section. The arrangement invariably led to nicknames like “Frying Pan” and “Tadpole.” Looks aside, however, the Hampden proved itself a most capable aircraft. Being fitted with Handley Page leading-edge slats, it could touch down at extremely low speeds. Moreover, it was faster than its two main rivals, the Wellington and the Arm – strong-Whitworth Whitley, and could carry nearly as heavy a bomb load over the same distance. As combat would demonstrate, the main deficiency of the Hamp

ton was its weak defenses. Nonetheless, by the advent of World War II in 1939, they constituted a major part of RAF Bomber Command.

Initial operations by Hampdens were restricted to reconnaissance and naval interdiction, as bombing Germany was forbidden. When a flight of 11 Hampdens was roughly handled on September 29, 1939, and five aircraft more were shot down on a reconnaissance mission, the craft were restricted to nighttime leaflet dropping. Hampdens were also utilized for mining operations off the German coast and made respectable torpedo-bombers. By 1940, however, daylight bombing missions were resumed during the Battle of France, and serious loss ensued. Hampdens were consequently fitted with heavier defensive armament and committed to nighttime bombing of German targets. Two squadrons were then dispatched to Murmansk for that purpose as well and were ultimately turned over to the Russians. Hampdens also managed to bomb Berlin on several occasions and successfully fulfilled various secondary capacities before retiring in 1942.

Type: Heavy Bombers

Dimensions: wingspan, 75 feet; length, 58 feet; height, 17 feet, 6 inches Weights: empty, 9,200 pounds; gross, 16,900 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 550-horsepower Rolls-Royce Kestrel liquid-cooled in-line engines Performance: maximum speed, 142 miles per hour; ceiling, 21,000 feet; range, 920 miles Armament: 3 x.303-inch machine guns; 3,500 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1933-1939

|

O |

ne of the stranger sights in the sky, the ungainly Heyford was the Royal Air Force’s last biplane bomber. It proved a fine machine and constituted a link between lumbering giants of the 1930s and the fast monoplane weapons of World War II.

In 1927 the Air Ministry issued Specification B.19/27, calling for a new heavy night bomber to replace the rapidly aging Vickers Virginia. Handley Page, where heavy bombers were a company specialty, submitted one of the most usual designs ever flown by any air force in the world. Simultaneously elegant yet grotesque, the Heyford was a biplane configuration with two wings of equal length fitted to a long, attenuated fuselage, with the tail unit sporting double rudders. What made the craft so unique was placement of the fuselage under the top wing, while the bottom span sat several feet below on struts! The center section of the bottom wing was also twice the thickness of the outboard ones to accommodate the bomb bay. Being low to the ground, this placement facilitated access by ground crews, and the entire

plane could be rearmed in under 30 minutes. It also featured a retractable “dustbin” turret to protect the underbelly. The Heyford was otherwise conventionally constructed of metal framework and canvas covering. The big craft flew well and proved easy to operate. Accordingly, in 1933 Heyfords entered the service as the last biplane bombers of the RAF.

At length 124 Heyfords were constructed in three models, and they equipped a total of 11 bombardment squadrons. They proved popular craft, strongly built, and during the 1935 RAF display at Hendon, one was actually looped! Commencing in 1937, following the appearance of Armstrong-Whit – worth Whitleys, the gangly Heyfords were slowly phased out of frontline service. By 1939 they had been completely displaced by Vickers Wellingtons, although several performed secondary functions like training and gilder-towing. The surviving machines were finally struck off the active list in 1941. Just prior to that, Heyfords served as testbeds for autopilots and experiments with radar navigation.

Type: Heavy Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 100 feet; length, 62 feet; height, 22 feet Weights: empty, 8,502 pounds; gross, 13,360 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 250-horsepower Rolls-Royce Mk II liquid-cooled in-line engines Performance: maximum speed, 97 miles an hour; ceiling, 8,500 feet; range, 800 miles Armament: 3 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 2,000 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1916-1920

|

T |

he O/400 was Britain’s first strategic bomber and, for many months, the largest aircraft assembled on the British Isles. It flew successful missions over Germany and also dropped the largest Allied bombs of the war.

Sir Frederick Handley Page established the first English factory solely dedicated to manufacturing airplanes in 1909. Six years later, the Admiralty issued specifications for a large two-engine patrolbomber, which they deemed “a bloody paralyzer.” In the spring of 1916, Handley Page responded with his model O/100. This giant craft was a three-bay biplane and powered by two tractor engines mounted in nacelles between the wings. The long, boxy fuselage was of conventional construction but featured a large biplane tail section. The craft was also unique for its time in that bombs were carried in a rudimentary bomb bay. That summer the O/100 entered production, with 42 being built. The Royal Navy initially employed them for maritime reconnaissance, but losses forced them to switch to nighttime bombing.

In the spring of 1917 a more refined version, the O/400, was introduced. This differed mainly in possessing more powerful engines and a fuel system that was relocated from the nacelles to the fuselage. This version was issued to the RAF’s Independent Force and equipped its very first strategic bomber units. In response to the various Gotha raids over London, the Air Board ordered the O/400s to hit back at the German mainland. On the evening of August 25, 1918, two machines from No. 215 Squadron did exactly that by staging a successful low-altitude (200 feet) raid that severely damaged a chemical factory in Mannheim.

Commencing that September, O/400s were dispatched over German targets in groups of 40 or so, both at day and night, with good effect. Some of these aircraft unloaded a 1,650-pound bomb—England’s biggest—on industrial targets in the Rhineland. By the time of the Armistice, 440 O/400s had been manufactured and were being supplanted by an even bigger craft, the V/1500. Both were replaced in turn by Vickers Vimys during the 1920s.

Type: Strategic Bomber; Tanker; Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 120 feet; length, 114 feet, 11 inches; height, 28 feet, 1 inch

Weights: empty, 91,000 pounds; gross, 233,000 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 20,600-pound thrust Rolls-Royce Conway turbofan engines

Performance: maximum speed, 640 miles per hour; ceiling, 55,000 feet; range, 2,300 miles

Armament: 35,000 pounds of conventional or nuclear bombs or missiles

Service dates: 1958-1984

|

T |

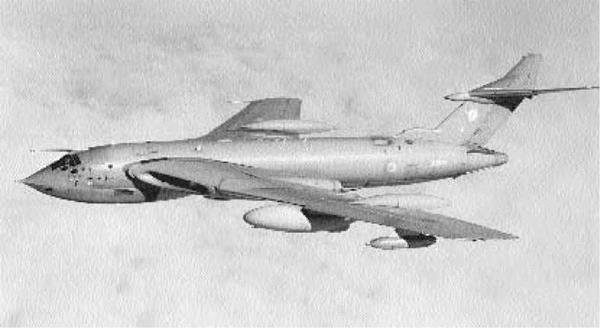

he graceful Victor was the last of Britain’s famous V-bombers. Technologically advanced when conceived, it was quickly outdated and performed more useful service in tanker and reconnaissance roles.

After World War II, and anticipating the technological trends of the day, Britain determined to maintain a strategic bombing force that would be jet-powered and carry atomic weapons. Specification B.35/46 was thus issued in 1946 to secure such aircraft, and Handley Page responded with a unique design quite different from its competitor, the Avro Vulcan. First flown in 1952, the Victor was a graceful, high-wing monoplane of rather sophisticated lines. The wing was crescent-shaped with decreasing degrees of sweep toward the tips. This arrangement allowed a constant critical Mach number over the wing for fast speed and high-altitude performance. The front fuselage was also unusual in that the front cabin was slightly podded and drooping while the rear was crowned by a high “T” tail, also of crescent design. The object of the Victor’s construction

was to enable higher speed and altitude than contemporary fighters. However, by the time it debuted in 1958, the Russians had perfected Mach 2 fighters and surface-to-air missiles. Thus, the first-model Victor, the B Mk 1, was obsolete as a nuclear strike craft from the onset. By 1964 several had been converted into K Mk 1 tankers to replace the aging and ailing Vickers Valiant.

The final version of the Victor, the B Mk 2, was redesigned as a low-altitude bomber and, hence, was fitted with a stronger, redesigned wing. It also possessed trailing-edge fairings to improve low-altitude maneuvering. With manned bombers being supplanted by guided missiles, however, it was decided to convert these aircraft into tankers as well. Several were also subsequently modified into SR Mk 2 strategic reconnaissance craft capable of photographing the entire Mediterranean in only seven hours. Four such craft could also cover the entire North Sea region in only six hours! These graceful machines were finally withdrawn from service in

1994.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 38 feet, 5 inches; length, 24 feet, 10 inches; height, 9 feet, 2 inches Weights: empty, 1,581 pounds; gross, 2,381 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 180-horsepower Argus As III liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 103 miles per hour; ceiling, 24,600 feet; range, 300 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns Service dates: 1918

|

D |

uring the final stages of World War I, the Hannover CL III was one of Germany’s best ground- attack aircraft. A distinctive biplane tail unit gave its gunner a wide field of fire, making it extremely dangerous to approach.

The firm Hannoversche Waggonfabrik AG was long employed in the manufacture of wooden rolling stock for railroads. Consequently, the firm was well situated to commence building wooden airplanes when so instructed by the German government in 1915. At first it manufactured Aviatik, Rumpler, and Halberstadt designs under license, but in 1917 lead engineer Hermann Dorner initiated the company’s first two-seat aircraft. This came in response to a new classification of aircraft, the CL, intended to act as fighter escorts to the slower, vulnerable C-series machines. This was undertaken in response to the growing effectiveness of Allied fighters.

The new aircraft, the Hannover CL III, was among the most unique German two-seaters deployed in the war. Constructed of wood and fabric, it featured a deep, plywood-covered fuselage that ta

pered to a knife-edge. The wings were of average span but closely placed to the fuselage, so the pilot enjoyed excellent vision forward and upward. Pilot and gunner sat in closely spaced tandem cockpits to facilitate communication. However, the CL III’s most notable asset was the unique biplane tail. This feature was usually associated with multiengine aircraft, but here it served a distinct purpose. The biplane structure enabled smaller tail surfaces to be utilized, granting the gunner unobstructed fields of fire.

The CL III entered service in the spring of 1918 and was extremely successful as an escort fighter and a ground-attack craft. It was fast, maneuverable, and could absorb tremendous damage. Moreover, the “Hannoveranas,” as they were dubbed by the British, were extremely tough customers to tackle. Being small and compact, they were frequently mistaken for single-seat fighters—until the gunner popped up and unleashed a hail of bullets. Nearly

1,0 of these excellent machines were constructed in three slightly differing versions before hostilities ceased.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 28 feet, 6 inches; length, 19 feet, 2 inches; height, 8 feet, 4 inches

Weights: empty, 882 pounds; gross, 1,334 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 120-horsepower Le Rhone rotary engine

Performance: maximum speed, 114 miles per hour; ceiling, 20,670 feet; range, 250 miles Armament: 1 x 7.7mm machine gun Service dates: 1917-1926

|

T |

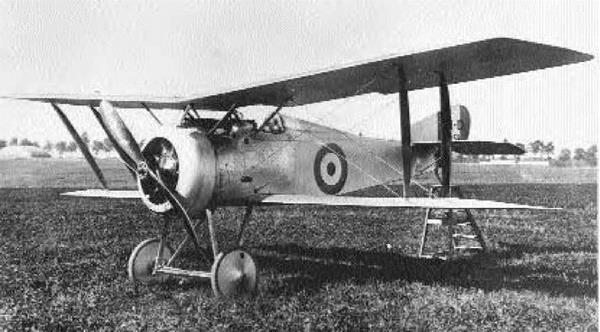

he nifty, compact HD 1 was one of World War I’s most agile fighters. Overlooked in France, it found fame in the service of Belgian and Italian forces.

Pierre Dupont had manufactured airplanes for several years prior to World War I and subsequently spent several months building Sopwith 1 1/2 Strutters under license. In 1916 he teamed with chief engineer Emile Dupont to design a new fighter to replace the aging French Nieuport scouts. The HD 1 emerged as a trim, handsome design with decidedly Sopwith overtones. It sported highly staggered wings, the top one exhibiting a pronounced dihedral. The fuselage was rectangular in cross-section, being made of wood and fabric-covered. This was then faired into a round metal cowling that housed a 120-horsepower rotary engine. The resulting craft was extremely maneuverable and highly responsive to controls. A potential weakness of the design was the armament, restricted to a single machine gun to save weight.

The French military liked the HD 1 but was already committed to building the bigger, more powerful SPAD VII and displayed no interest. Fortunately, an Italian military deputation tested it during the winter of 1916 and, delighted by its performance, placed an immediate order for 100 machines. As demand for HD 1s proved insatiable, the Italian firm Nieuport-Macchi began producing them under license. The little fighter enjoyed tremendous success along the Italian front, and a leading ace, Tenente Scaroni, scored most of his victories flying it. HD 1s were also exported to Belgium, where they likewise became highly popular. Noted Belgian ace Willy Coppens scored most of his 37 kills in an HD 1. Moreover, when the British offered to replace them with formidable Sopwith Camels in 1918, the Belgian pilots refused. Their beloved HD 1s remained in frontline service until 1927. Several were also exported to the United States and Switzerland, where they functioned as trainers. A total of 1,145 of these nimble aircraft were produced in France and Italy.