. Beriev MBR 2

Type: Reconnaissance; Patrol-Bomber; Antisubmarine

Dimensions: wingspan, 62 feet, 4 inches; length, 4 feet, 3 inches; height, 14 feet, 9 inches

Weights: empty, 5,456 pounds; gross, 9,039 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 680-horsepower M-17B air-cooled in-line engine

Performance: maximum speed, 124 miles per hour; ceiling, 14,435 feet; range, 404 miles

Armament: 2 x 7.62mm machine guns; up to 1,102 pounds of bombs or depth charges

Service dates: 1935-1965

|

T |

he simple, rugged MBR 2 was built in large quantities and enjoyed a 30-year service life. At one time or another circumstances forced it to perform reconnaissance, bombing, and antisubmarine work.

In 1932 the talented designer Georgi M. Beriev submitted plans for his first flying boat, a machine intended for short-range maritime reconnaissance. Designated the MBR 2, it was a shoulder-wing monoplane with a pusher-mounted engine affixed by a pair of “N” struts. It had a wooden, two-step hull and a wing constructed of metal tubing covered by fabric. A crew of four was comfortably carried in open cockpits and gunnery stations, but subsequent versions introduced fully enclosed canopies and manually operated turrets. The new craft was simple and efficient from the onset, so in 1935 it entered service with Soviet naval units in the Black Sea and elsewhere. In service the MBR 2 established its designer’s reputation for creating simple, robust aircraft that worked well on water and were easily maintained. Production ended in 1941 after a run of

1,300 machines. The MBR 2 was also popular with civilians, and in 1937 noted aviatrix Paulina Os – ipenka established several women’s world records flying one of them.

The MBR 2 was marginally obsolete by 1939, but it served in considerable numbers throughout the war with Finland. When the Great Patriotic War commenced in June 1941, the MBR 2s were necessarily deployed everywhere that the Soviet navy fought and performed yeoman’s work. In addition to maritime reconnaissance, the exigencies of combat required it to undertake night bombing and, in the absence of other machines, day bombing as well. Despite fierce German resistance, many MBR 2 simply absorbed great amounts of damage and returned home for more missions. In addition, the type’s slow speed and long loitering ability made it an ideal antisubmarine platform. After the war, many MBR 2s found their way into fishery and air/sea rescue work. They remained so employed until being replaced by the newer Be 12 in the mid-1960s.

Type: Transport

Dimensions: wingspan, 162 feet; length, 99 feet, 5 inches; height, 38 feet, 9 inches

Weights: empty, 79,234 pounds; gross, 135,000 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 2,850-horsepower Bristol Centaurus radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 238 miles per hour; ceiling, 16,000 feet; range, 1,300 miles

Armament: none

Service dates: 1956-1967

|

O |

ne of the bulkiest aircraft ever conceived, the Beverly was a dependable heavy-lifter that served capably for a decade. It had uncanny abilities to take off and land on very short strips, even when fully loaded.

In the immediate postwar era, the British Air Ministry issued Specification C.3/46 to secure a new and advanced tactical transport for the Royal Air Force (RAF). Such a plane had to be capable of carrying very large loads over medium distances. It so happened that the General Aircraft Corporation had conducted several studies of large freighter airplanes and had a design in hand. When a contract was authorized, the construction commenced and continued apace until 1949, when the company merged with Blackburn. The finished product finally flew as the GAL 60 Universal in June 1950. This was an odd bird, to say the least. The new plane centered around a large and capacious fuselage that was very deep if somewhat narrow. To this was connected a large tailboom sporting twin rudders, which could also hold cargo or troops. The shoulder-mounted

wing also had four Bristol Hercules radial engines, while a pair of long, fixed landing gear were attached. Test flights revealed the craft lifted prodigious quantities of freight using very short runways and could touch down in even shorter spaces. With further modifications a newer craft, christened the Beverly, entered production in 1955. These became operational the following year; Blackburn ultimately constructed 47 machines.

In service the Beverly was the largest airplane operated by the RAF to that time. It could accommodate several light vehicles or up to 94 troops. It was also the first such craft equipped with clamshell rear doors for air-dropping supplies. In 1959 a Beverly tossed out a military load in excess of 40,000 pounds, then a national record. The big craft performed particularly useful service ferrying helicopters to the troubled island of Cyprus. They served RAF Transport Command well for a decade with little ceremony before finally being replaced in 1967 by the even more capable Lockheed C-130 Hercules.

Type: Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 44 feet; length, 63 feet, 5 inches; height, 16 feet, 3 inches

Weights: empty, 30,000 pounds; gross, 62,000 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 11,030-pound thrust Rolls-Royce Spey turbofan engines

Performance: maximum speed, 691 miles per hour; ceiling, 40,000 feet; range, 600 miles

Armament: up to 16,000 pounds of bombs or missiles

Service dates: 1962-1992

|

T |

he massive Buccaneer was the world’s first aircraft employed for high-speed low-altitude bombing. Nimble despite great bulk, Buccaneers could deliver a wide range of ordnance beneath enemy radar nets with remarkable accuracy.

In 1952 the Royal Navy issued Specification NA.39 calling for the creation of a two-seat, low-level strike aircraft capable of carrier operations. Such a machine would perform at high subsonic speed—a difficult proposition due to atmospheric density—yet possess considerable range. In 1955 Blackburn responded with a design that first flew in 1958. The Buccaneer was a large, portly aircraft with swept, midmounted wings and a high “T” tail. To facilitate high speed at low levels it utilized a unique boundary layer control system whereby hot gas was bled from the engines and ejected at certain points along the leading edges. This controlled the amount of air passing over the control surfaces and ensured a smooth ride. Other innovations included a rotary bomb bay, which turned inside the fuselage and thus did not

project doors into the slipstream. Finally, the fuselage incorporated area ruling, being pinched in toward the rear, again to ensure high speed. Flight trials were impressive, and the Buccaneer moved into production. The first S.1 models reached the Royal Navy carriers by 1961, and in service they proved fine bombing platforms, if somewhat underpowered. The S.2 versions, fitted with Rolls-Royce Spey engines with 30 percent more thrust and better fuel economy, arrived in 1964. Some 100 Buccaneers of both versions were built.

By 1969 British defense cuts had all but gutted the Fleet Air Arm of carrier aircraft, and surviving Buccaneers were passed along to the Royal Air Force (RAF). At first, the RAF looked askance at the brutish machines because they lacked supersonic capability, but the Buccaneers, once outfitted with better electronics, performed as formidable strike aircraft. These were slowly replaced by the newer Panavia Tornadoes beginning in 1984, but a handful flew missions during the 1991 Gulf War. They were superb interim machines.

Type: Reconnaissance; Torpedo-Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 46 feet; length, 35 feet, 3 inches; height, 12 feet, 1 inch

Weights: empty, 4,039 pounds; gross, 8,050 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 800-horsepower Bristol Pegasus radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 150 miles per hour; ceiling, 16,000 feet; range, 625 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns; 1 x 1,550-pound torpedo Service dates: 1935-1944

|

T |

he Shark was the last in a long line of Blackburn torpedo planes and could operate as either a land plane or on floats. It had a relatively short service life, but lingered in reserve functions for many years.

In 1933 the Fleet Air Arm needed a new two – or three-seat torpedo-bomber to update its aging fleet of Blackburn Darts, Ripons, and Baffins. Blackburn responded with a prototype originally begun as a private venture, the M.1/30A, which first flew on February 24, 1933. It was a biplane with unequal wings, the top of which possessed a broad chord and a cut-out section over the pilot’s canopy. The two wings were metal-framed, fabric-covered, and fastened by distinctive “N”-type struts. Interestingly, both spans possessed ailerons that could be lowered as flaps. Finally, the fuselage was round in cross-section, being an all-metal, semimonocoque structure with watertight compartments. Tests on board the carrier HMS Courageous proved satisfactory, and in 1934 16 aircraft were acquired as the Shark I. These

served with No. 820 Squadron, replacing their complement of Fairey Seals.

In 1935 a newer version, the Shark II, was developed that featured a new Armstrong-Whitworth VI Tiger radial engine developing 750-horsepower. The Royal Navy purchased 123 of this version for use in No. 810 and No. 821 Squadrons, supplanting their inventory of Fairey Seals and Blackburn Baffins. The Shark II was an efficient plane, but in 1938 it was replaced in turn by the newer Fairey Swordfish and assigned to training functions.

A final variant, the Shark III, emerged in 1937. This differed from the previous models in having a glazed sliding canopy and a three-blade wooden propeller. It was also powered by an 800-horsepower Bristol Pegasus radial engine. The navy acquired 95 Shark IIIs that year, and they served briefly before assuming training and target-towing duties. Several Shark IIIs still operated in the opening days of World War II, and a handful at Trinidad flew regular training missions until 1944. Production reached 238 machines.

Type: Fighter; Dive-Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 46 feet, 2 inches; length, 35 feet, 7 inches; height, 12 feet, 6 inches

Weights: empty, 5,490 pounds; gross, 8,228 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 890-horsepower Bristol Perseus XII radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 225 miles per hour; ceiling, 20,200 feet; range, 760 miles

Armament: 5 x.303-inch machine guns; 500 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1938-1942

|

T |

he Skua is best remembered as the Fleet Air Arm’s first carrier-based monoplane. Hopelessly outdated by World War II, it performed a few memorable tasks before being retired.

In 1934 the British Air Ministry, seeking a new aircraft to replace its Hawker Ospreys and Nim – rods, issued Specification O.27/34, which called for an all-metal monoplane capable of being deck-handled on a carrier and flown as either a fighter or a dive-bomber. The prototype Blackburn Skua first flew in 1937 as a low-wing monoplane, the first Fleet Air Arm machine to possess a radial engine, retractable landing gear, and a variable-pitch propeller. The design was underpowered but pleasant to fly, so in 1938 it entered service aboard the carrier HMS Ark Royal. The advent of World War II clearly demonstrated the shortcomings of the Skua as a fighter, as it was too slow and underarmed to be effective. On September 25, 1939, a Skua managed— barely—to shoot down a lumbering Do 18 seaplane,

the first official kill by Fleet Air Arm aircraft. However, Skuas were better employed as dive-bombers, and they performed heroic work in the early campaigns around Norway. On April 10, 1940, 16 Skuas took off from Hatson in the Orkneys and flew directly to the Bergen Fjord. There they surprised and sank the German heavy cruiser Konigsberg at dawn and returned home with the loss of only one plane. Skuas remained in frontline service until 1941, when they were phased out by Fairey Fulmars and Hawker Sea Hurricanes. Many spent the rest of the war performing target-tug and training duties. A total of 192 were built.

In 1938 an attempt was made to convert the Skua into an effective turret-armed fighter, much in the manner of Bolton-Paul’s Defiant. The resulting design was called the Roc, but it proved even slower and more incapable than its predecessor. Blackburn assembled 136 of these machines, but they saw no combat and very little active service.

Type: Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 25 feet, 7 inches; length, 26 feet, 3 inches; height, 8 feet, 6 inches Weights: empty, 769 pounds; gross, 1,378 pounds Power plant: 1 x 70-horsepower Gnome rotary engine

Performance: maximum speed, 66 miles per hour; ceiling, 3,000 feet; range, 200 miles Armament: up to 55 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1910-1915

|

T |

he fragile-looking Bleriot XI crossed the English Channel to tally one of history’s most significant aviation firsts. In the early days of World War I, it was also operated by numerous French, British, and Italian squadrons.

Prior to 1908, Louis Bleriot had been an aviator of little consequence, that is, until he abandoned biplane pusher-type craft in favor of monoplane tractor designs. His greatest effort, the Bleriot XI, premiered at Paris in December 1908. This revolutionary craft consisted of steel tubing, wooden struts, a fabric – covered fuselage, and paper-covered wings. It possessed a conventional rudder but was assisted in turns by wing-warping, whereby the wing’s trailing edges were bent during flight by wires. The craft landed on two bicycle tires suspended on struts and was initially powered by a coughing, 25-horsepower REP engine. The Bleriot XI seemed to epitomize the fragility of early flight, but in fact it was a well-conceived aircraft with high performance for its day. Bleriot underscored this fact on July 25, 1909, when he dramatically piloted his craft across the English

Channel—the first time such a feat had been accomplished. This act gained him international celebrity and dramatically signified that technology had ended England’s isolation from continental Europe.

The French military acquired its first Bleriot XI in 1910 and went on to develop specialized versions with more powerful engines for reconnaissance and artillery-spotting. The craft was also acquired in large numbers by Italy, and on October 23, 1911, Captain Carlo Piazza conducted history’s first reconnaissance mission by overflying Turkish positions in Libya. Following the onset of World War I in August 1914, the Bleriot was among the most numerous aircraft in a host of French, Italian, and British reconnaissance squadrons. In service it was slow and unarmed save for crew-carried rifles, but Bleriots could also carry small, hand-thrown bombs for harassment purposes. These pioneering craft rendered useful service well into 1915 before being withdrawn to serve as trainers. Prior to their removal, the Bleriots made history by demonstrating the utility of military aviation. About 800 were constructed.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 29 feet; length, 24 feet, 5 inches; height, 12 feet, 2 inches Weights: empty, 2,765 pounds; gross, 3,638 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 690-horsepower Hispano-Suiza 12Xbrs water-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 201 miles per hour; ceiling, 34,450 feet; range, 497 miles Armament: 2 x 7.7mm machine guns Service dates: 1937-1939

|

T |

he handsome S 510 took six and a half years to develop before becoming the last biplane fighter to serve the French Armee de l’Air. Although superbly acrobatic, it was too outdated to see action in World War II.

In 1930 the French government announced competition for a new fighter. Three years later Andre Herbemont responded with the last biplane product to bear the old SPAD designation. His new craft was a single-bay biplane with fixed landing gear. The wings were equally long, but the upper was swept sharply back, and both were joined by single, faired “I” struts. Ailerons were present on the lower wing only. In contrast to the previous round-bodied fighters, the new design possessed an oval cross-section fuselage with the rear section forming a duralumin monocoque. The airplane frame was built entirely of metal, was fabric-covered, and sported an open cockpit. In a final touch, spatted wheel fairings gave it a sleek, modern look. The Bleriot-SPAD S 510 was certainly a handsome craft with outstanding ma

neuverability and climb. However, in level flight it was slower than the Dewoitine D 510 all-metal monoplane, to which it lost the competition. The government then suggested that test models be lengthened to improve longitudinal stability. When Herbemont complied, 60 aircraft were ordered in

1936— six years after the design had been originated.

In service the S 510 proved delightful to fly, as were all SPAD fighters. However, even lengthened it was prone to spin, and at steep angles the engine could stall due to fuel starvation. Moreover, several accidents occurred as a result of undercarriage breakage. These deficiencies ensured that the S 510 enjoyed only brief service life, and by 1937 most had been transferred to regional (reserve) squadrons. Reputedly, a handful were clandestinely supplied to Spanish Republican forces during the Spanish Civil War. S 510s were still available in quantity when World War II commenced in September 1939, but none saw combat. If employed at all, the last French biplane fighter performed its final duties as a trainer.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 34 feet, 7 inches; length, 29 feet, 10 inches; height, 12 feet, 11 inches

Weights: empty, 4,453 pounds; gross, 5,908 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 1,080-horsepower Gnome-Rhone 14N-25 radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 320 miles per hour; ceiling, 32,810 feet; range, 373 miles

Armament: 2 x 7.5mm machine guns; 2 x 20mm cannon

Service dates: 1939-1942

|

T |

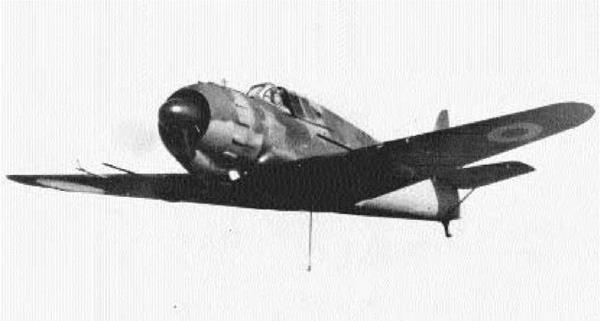

he MB 152, having suffered a prolonged, troubled gestation, only entered service on the eve of World War II. It nonetheless formed a major part of French fighter strength and gave a good account of itself.

In 1934 the French Air Ministry issued specifications for a new monoplane fighter. Five companies responded and one, Marcel Bloch Avions, fielded the MB 150. This was an all-metal, low-wing monoplane with retractable undercarriage. However, the prototype was extremely underpowered, and on its first test hop it failed to leave the ground. A complete redesign became necessary, and it was not until May 4, 1937, that a test flight successfully concluded. Further modifications were required to make the craft suitable for mass production, and in 1939 the first MB 151 was accepted into service by the Armee de l’Air. Continued testing revealed their unsatisfactory nature as fighters, and the first 140 machines were used as trainers. Fortunately for Bloch a new version, the MB 152, was already under development. This was similar to the earlier version

but enjoyed revised wings and a stronger GR 14N radial engine. In flight the MB 152 displayed good maneuverability, was a stable gun platform, and could outdive other fighters with ease. More political wrangling followed, but the government finally assented to procuring an additional 482 aircraft.

When World War II commenced in September 1939, the French possessed 140 MB 151s and 383 MB 152s, but the majority had been delivered without gun sights or propellers. Much valuable time was lost making them combat-worthy, and further efforts were expended correcting a tendency toward overheating. When Germany finally invaded France on May 10, 1940, no less than seven groupes de chasse (fighter groups) were equipped with MB 152s. Of these, only 80 were truly operational, but all were committed to combat against the mighty Luftwaffe. By the time fighting ceased, 270 of these attractive machines had been lost in action, but they accounted for 170 German aircraft. A total of 600 machines had been built.

Type: Reconnaissance; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 58 feet, 8 inches; length, 40 feet, 2 inches; height, 11 feet, 7 inches

Weights: empty, 12,346 pounds; gross, 15,784 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 1,100-horsepower Gnome-Rhone 14N-48/49 radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 329 miles per hour; ceiling, 36,090 feet; range, 1,025 miles

Armament: 7 x 7.5mm machine guns; up to 882 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1939-1953

|

T |

he elegant Bloch MB 174 was France’s best reconnaissance aircraft of World War II. Fast enough to escape marauding Luftwaffe fighters, they had little opportunity to distinguish themselves.

In 1936 Bloch initiated work on a modern, two – or three-seat reconnaissance bomber for the French Armee de l’Air. The prototype first flew in February 1938 as an all-metal, twin-engine, low-wing monoplane. The craft was fitted with twin rudders, as well as retractable landing gear that buried itself in the engine nacelles. This first model possessed an elongated cupola under the fuselage to house a camera or an additional gun position, but this feature was deleted on subsequent models. By January 1939, the aircraft had evolved into the Bloch MB 174, with major modifications. It featured a lengthy greenhouse canopy set farther back along the fuselage than the prototypes. It also possessed an extensively glazed nose and a small bomb bay. Test flights revealed the craft to exhibit excellent performance at all altitudes, so in 1939 it entered production. Persis

tent problems with overheating resulted in the adoption of smaller propeller spinners on most machines. A small number of bomber versions, the MB 175, had also been constructed. Around 80 machines were built in all.

Bloch MB 174s equipped three groupes de reconnaissance (reconnaissance groups) by the spring of 1940, shortly before the German invasion. At that time they were required to conduct dangerous missions deep into enemy territory, which were accomplished with little loss. With the imminent collapse of France, several MB 174s were flown to North Africa to escape, but most of these excellent craft were destroyed to prevent capture. The surviving machines were subsequently employed by Vichy air units in the defense of Tunisia. The Germans also kept the type in production, taking on 56 machines as trainers. During the immediate postwar period, an additional 80 MB 174Ts were constructed as torpedo-bombers for the French navy. These flew capably until being replaced in 1953 by more modern designs.