. Etrich Taube Austria-Hungary/Germany

Type: Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 47 feet, 1 inch; length, 32 feet, 3 inches; height, 10 feet, 4 inches

Weights: empty, 1,323 pounds; gross, 1,918 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 100-horsepower Mercedes-Benz liquid-cooled engine

Performance: maximum speed, 71 miles per hour; ceiling, 9,840 feet; range, 240 miles

Armament: none, but small bombs could be carried

Service dates: 1914-1915

|

T |

he beautiful Taube (Dove) was one of the world’s earliest effective warplanes. Despite a seemingly frail persona, it was among the very first aircraft to conduct bombing runs.

Since its inception in 1903, aviation technology continued advancing and improving in leaps and bounds. In 1910 Austrian designer Igo Etrich designed what was to become the first of an entire series of famous warplanes. Christened the Taube, it was a sizable monoplane whose wingtips flared back in the shape of a large bird’s wing. Because ailerons had not yet been invented, the craft was turned by a process known as wing-warping in which lateral control during flight was achieved by bending the rudder and wingtips using wires. The resulting craft proved pleasant to fly, and in July 1914 a Taube broke the world altitude record by reaching 21,600 feet. Knowledge of Etrich’s invention led to its exportation to Italy, Turkey, and Japan. The design proved so popular that the firm Rumpler also obtained a license to manufacture it in Germany.

Despite its lovely appearance and gentle characteristics, the Taube was immediately pressed into military service. On November 1, 1911, Lieutenant Giulio Gavotti conducted the first bombing raid in history when he tossed hand grenades out of his cockpit during the Italian-Turkish War in Libya. On August 13, 1914, Lieutenant Franz von Hiddeson flew from the Marne River and unloaded four small bombs on Paris for the first time. This was followed up by a Taube flown by Max Immelmann, a future ace, who dropped leaflets on the city demanding its immediate surrender! On the other side of the world, a Taube formed part of the German garrison defending Tsing – tao (Qingdao), China, during a siege by Japanese and British forces. In that instance Lieutenant Gunther Plutschow dropped several bombs and fought off attacks by Japanese-manned Nieuport and Farman fighters. Despite this auspicious combat debut, the Taube had been replaced in 1915 by better machines and relegated to training functions. Around 500 had been constructed by six different firms.

Type: Torpedo-Bomber; Dive-Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 49 feet, 2 inches; length, 39 feet, 9 inches; height, 12 feet, 3 inches Weights: empty, 10,818 pounds; gross, 14,250 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 1,640-horsepower Rolls-Royce Merlin 32 liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 240 miles per hour; ceiling, 16,600 feet; range, 1,150 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 1,600 pounds of bombs or torpedoes Service dates: 1943-1953

|

T |

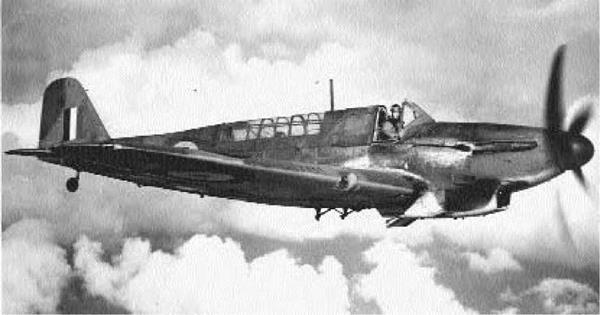

he Barracuda was the Royal Navy’s first monoplane torpedo-bomber. Underpowered and somewhat ungainly in appearance, it nonetheless fulfilled a wide variety of missions.

In 1937 the Air Ministry issued Specification S.24/37 to secure a new torpedo-bomber to replace the seemingly obsolete Fairey Swordfish biplanes. The new craft was envisioned as a three-seat, allmetal monoplane with good speed and carrying capacity. Fairey drew up plans for such a craft early on, but developmental problems with the new Rolls-Royce Exe engine delayed production by three years. Eventually, another low-powered substitute had to be fitted, and the prototype Barracuda did not take flight until December 1940. It emerged as a distinctive-looking machine with shoulder wings that sported broad Youngman flaps on the trailing edge and a very high tail. For its size and weight, the craft handled exceedingly well. But when additional production delays ensued, the first Barracudas did not reach the Fleet Air Arm until the spring of 1943. Nonetheless, they represented

the first monoplane torpedo-bombers employed by that service.

The Barracuda was a welcome addition to the fleet, for it proved extremely adaptable when fitted with a succession of stronger power plants. In service they were mounted with a bewildering array of radars, weapons, and other devices. And although the Barracuda was designed as a torpedo-bomber, the lack of Axis shipping meant they were more actively deployed as dive-bombers. Their most famous action occurred on April 3, 1944, when 42 Barracudas were launched against the German battleship Tirpitz at Kaafiord, Norway. Appearing suddenly at dawn, they successfully negotiated the steep-sided fjord, scoring 15 direct hits. Subsequent strikes were also orchestrated throughout May-August of that year. The Barracuda received its Pacific-theater baptism of fire on April 21, 1944, when several raided Japanese-held islands in Sumatra. Most Barracudas were retired immediately after the war, but several were retained for antisubmarine duty until replaced by Grumman Avengers in 1953. Production totaled 2,602 machines.

Type: Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 54 feet; length, 42 feet, 4 inches; height, 15 feet, 6 inches Weights: empty, 6,647 pounds; gross, 10,792 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 1,030-horsepower Rolls-Royce Merlin I liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 257 miles per hour; ceiling, 25,000 feet; range, 1,000 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns; 1,000 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1937-1945

|

T |

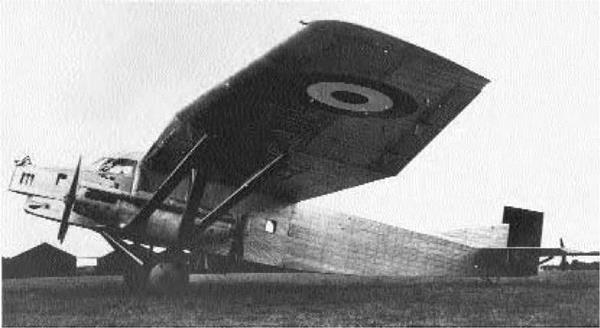

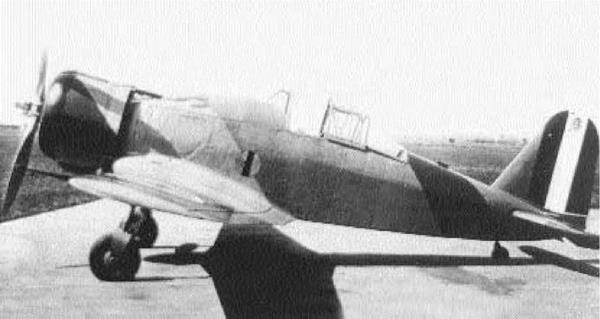

he Battle marked great aeronautical advances and was vastly superior to biplane contemporaries. However, it was hopelessly outdated in World War II and suffered severely during the Battle of France.

The Fairey Battle evolved out of Specification P.27/32, which was issued in 1932 to replace older Hawker Harts and Hind biplane bombers with more modern aircraft. The prototype Battle debuted in 1936, the very model of aerodynamic efficiency. It was a streamlined, all-metal, low-wing monoplane with retractable undercarriage and sheeted skin. A crew of three sat in a long greenhouse canopy. Test flights revealed that it carried twice the bomb load of the older planes at 50 percent higher speeds. Appreciably, the Air Ministry accepted it gleefully, and the first Battle squadrons began forming in 1937. It became one of the major types produced during expansion of the RAF in the late 1930s. By the advent of World War II, the RAF possessed more than 1,000 Battles in frontline service.

The Battle enjoyed a brief and rather tragic wartime career with the Advanced Air Striking Force in France. There, on September 20, 1939, a Battle tailgunner shot down the first German aircraft claimed in the West. However, this jubilation dissipated 10 days later when five Battles on a reconnaissance flight were jumped by Bf 109s and only one survived. The German invasion of France then commenced in May 1940, and casualties increased exponentially. On a daylight mission against the Maastricht bridges on May 10, 1940, the Battles lost 13 of 32 unescorted aircraft. This tragedy also occasioned the first Victoria Cross awarded, posthumously, to an RAF crew. An even bigger disaster occurred four days later when German fighters clawed down 32 of 63 Battles intent on hitting bridgeheads at Sedan. The surviving craft were immediately withdrawn from service and spent the rest of the war in training duties. Others performed useful service as target tugs in Canada and Australia.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 44 feet, 6 inches; length, 37 feet, 7 inches; height, 13 feet, 7 inches Weights: empty, 9,750 pounds; gross, 14,020 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 1,730-horsepower Rolls-Royce Griffon IIIB liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 316 miles per hour; ceiling, 28,000 feet; range, 1,300 miles Armament: 4 x 20mm cannons; up to 2,000 pounds of bombs or rockets Service dates: 1943-1956

|

T |

he fearsome Firefly was the Royal Navy’s most capable two-seat fighter of World War II. It was the first British plane to overfly Japan and later saw service during the Korean War.

Designed to fulfill Naval Specification N.5/50, the Fairey Firefly arose from the need to replace the relatively modern yet obsolete Fulmar two-seat fighter. The prototype first flew in December 1941 and greatly resembled the earlier machine. The Firefly was a low-wing, all-metal monoplane, with folding wings for carrier storage. The pilot sat up front near the leading edge while the radio opera – tor/observer was located some distance aft. Like the earlier Barracuda, it employed broad Youngman flaps on the wings’ trailing edges, and these were mechanically recessed into the wing when not in use. The powerful Rolls-Royce Griffon 61 engine also required a large “chin” radiator that gave the craft a distinctly pugnacious profile. Tests were entirely successful, and the Firefly exhibited lively performance that belied its size. The first units

reached the Fleet Air Arm in the summer of 1943 and served with distinction in both the European and Pacific theaters. Its armament of four 20mm cannons was regarded as particularly hard-hitting.

Perhaps the Firefly is best remembered for a reconnaissance flight that resulted in the sinking of the German battleship Tirpitz in July 1944. It also harassed Japanese aircraft and ground installations throughout the East Indies, and in July 1945 a Firefly became the first British aircraft to overfly Tokyo. After the war a more powerful version was introduced, the Mk IV, which featured a Rolls-Royce Griffon 74 engine without the distinctive radiator; it had a four-blade propeller and clipped wings. This version fought in Korea with the Royal Navy and Australian forces. Successive modifications kept this craft in frontline service as an antisubmarine aircraft until the appearance of the Fairey Gannet in 1956. Over the course of a 13-year career, 1,638 Fire – flys were built and operated by the navies of England, Australia, Canada, and the Netherlands.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 29 feet; length, 22 feet, 10 inches; height, 10 feet Weights: empty, 2,038 pounds; gross, 3,028 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 410-horsepower Armstrong-Siddeley Jaguar IV radial engine Performance: maximum speed, 134 miles per hour; ceiling, 19,000 feet; range, 263 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 80 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1923-1934

|

T |

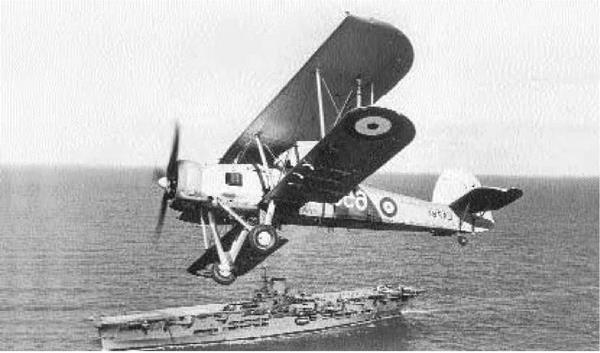

he homely but capable Flycatcher was among the Fleet Air Arm’s longest-serving airplanes. For nearly a decade it constituted the only fighter craft available to British carriers.

Designed to a 1922 Air Ministry specification, the Fairey Flycatcher enjoyed an illustrious career unique in the annals of naval aviation. The prototype materialized as a single-bay biplane of singularly grotesque appearance. The wood and metal fuselage was covered in fabric and terminated in a long, low rudder. Significantly, it canted upward just aft of the cockpit, giving the craft a decidedly “bent” look. The two wings were of equal length, but the upper one displayed dihedral, and both were fitted with a de – vice—the Fairey Patent Camber Gear—across the trailing edges, which was an extended flap that could be lowered for greater lift during takeoff and for braking upon the landing approach. The Flycatcher was also the first British carrier aircraft to utilize hydraulic brakes. All told, it was an ugly but functional machine that was strong and could dive

steeply in complete safety. But what pilots remember most was its superlative maneuverability. The Flycatcher was forgiving, easy to fly, and outturned anything with wings. This extraordinary aircraft joined the Fleet Air Arm in 1923 and remained its star performer for nearly 11 years.

During the 1920s, the rugged Flycatchers demonstrated their utility as carrier aircraft by launching without the benefit of catapults. They alighted so readily that the 60-foot tapered runway situated below the main carrier flight deck could be utilized to shoot out over the bow. Flycatchers performed similar feats while flying off platforms attached to the turrets of capital ships. They also helped pioneer a tactic known as “converging bombing” whereby three aircraft simultaneously swooped down on a target from three different directions. The versatile Flycatcher was a common sight on carrier decks until 1930, when it was gradually replaced by Hawker Nimrods. A total of 192 of these classic fighters were built.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 46 feet, 4 inches; length, 40 feet, 2 inches; height, 10 feet, 8 inches Weights: empty, 7,051 pounds; gross, 10,200 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 1,080-horsepower Rolls-Royce Merlin VIII liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 272 miles per hour; ceiling, 27,200 feet; range, 780 miles Armament: 8 x.303-inch machine guns; 500 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1940-1945

|

T |

he Fulmar was the Fleet Air Arm’s first eight – gun fighter. Although slower than land-based German adversaries, it performed useful service against the Regia Aeronautica (Italian air force).

By 1938 the British Admiralty felt a pressing need for more modern fighter craft, one mounting eight machine guns like the Hawker Hurricanes and Supermarine Spitfires then coming into service. However, unlike the land-based fighters, Fleet Air Arm requirements necessitated inclusion of a second crew member to act as navigator. This was deemed essential for ensuring that the aircraft could safely return to a carrier at night or in bad weather. It was recognized from the onset that the basic attributes of the new machine would be range and firepower, not speed. In 1938 a Fairey deign team under Marcel Lo – belle took the existing P.3/34 light bomber prototype and converted it into a two-seat fighter. The new Fulmar prototype first flew in 1940, exhibiting many fine qualities. It was maneuverable, easy to handle, and functioned well on the deck. But as anticipated, the

added weight of a second crew member rendered its performance somewhat disappointing. Nevertheless, the Fleet Air Arm needed an immediate replacement for its aging Blackburn Skuas and Rocs, so the craft entered production that year.

Fulmars debuted aboard the carrier HMS Ark Royal in the summer of 1940 and fought extensively during the defense of Malta. Its somewhat slow speed was considered no great disadvantage while tangling with lower-powered Italian aircraft, and its heavy armament made it lethal to enemy bombers. In an attempt to improve performance a new version, the Fulmar II, was introduced in 1943, featuring the more powerful Merlin 32 engine. By this time, however, Fulmars were being replaced by infinitely better Sea Hurricanes and Sea Spitfires. They subsequently completed additional useful work as night fighters before being phased out by 1945. Despite their sometimes sluggish performance, Fulmars performed well on balance and frequently under trying circumstances.

Type: Reconnaissance; Liaison

Dimensions: wingspan, 45 feet, 9 inches; length, 35 feet, 6 inches; height, 14 feet Weights: empty, 3,923 pounds; gross, 6,300 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 570-horsepower Napier Lion X1A liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 130 miles per hour; ceiling, 20,000 feet; range, 400 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 550 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1928-1940

|

T |

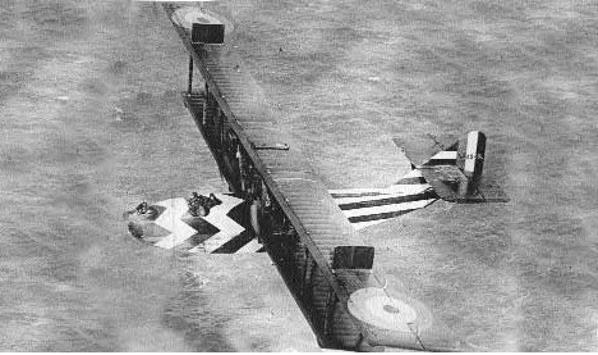

he venerable Fairey IIIF was the most numerous aircraft of the Fleet Air Arm between the wars. Deployed from every British carrier, it served extensively around the world.

The famous Fairey III series first flew in 1917, although it was developed too late for combat in World War I. For 10 years thereafter, these capable aircraft, built in both land and seaplane configurations, saw widespread service with the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force.

In 1924 the Air Ministry announced Specification 19/24, which called for a new two-seat general purpose aircraft for the RAF and a three-seat version of the Fleet Air Arm. Consequently, Fairey took a standard IIID model and made numerous modifications to the point where it was virtually a new airplane. Like all Fairey IIIs, this craft was a conventional biplane with equal-span two-bay wings made of wood and fabric. The IIIF version differed by having a metal-framed fuselage, covered in fabric as before but also sporting an extremely tight-fitting, streamlined cowling. The various changes greatly

enhanced its performance, and in 1927 the first Fairey IIIFs became operational.

The RAF employed Fairey IIIFs as general-purpose communications aircraft, and they were also capable of long, record-breaking flights. As an example, several Capetown-to-Cairo flights were performed throughout the early 1930s, including one headed by Lieutenant Commander A. T. Harris (who later became famous as “Bomber Harris”). In naval service, many Fairey IIIFs were fitted with twin floats and operated off of capital ships. Others, with landing gear, were flown from every carrier in the Royal Navy, with service as far afield as Hong Kong. They also supplanted the aging fleet of Avro Bisons, Blackburn Blackburns, and Blackburn Ripons stationed there. Toward the end of a long service life, three Fairey IIFs were converted into radio-controlled target drones known as Fairey Queens. The RAF machines were phased out of service beginning in 1935, but naval versions were not declared obsolete in 1941. A total of 622 of these efficient aircraft were constructed.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 45 feet, 6 inches; length, 35 feet, 8 inches; height, 12 feet, 4 inches

Weights: empty, 4,700 pounds; gross, 7,510 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 750-horsepower Bristol Pegasus radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 138 miles per hour; ceiling, 10,700 feet; range, 1,030 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 1,680 pounds of bombs, rockets, or mines Service dates: 1936-1945

|

D |

uring World War II, the archaic-looking “String – bag” sank more Axis tonnage than any other British aircraft. It successfully accomplished a wide variety of tasks and actually outlived the aircraft intended to replace it.

The legendary Swordfish evolved in response to a 1933 Air Ministry specification calling for a new torpedo/reconnaissance aircraft. Fairey Aviation enjoyed a long tradition of building excellent naval machines, and its prototype TSR 2 was no exception. It was a two-bay biplane of metal structure, covered in fabric throughout. The upper wing was slightly swept back, and provisions were made for a crew of three in open cockpits. When accepted for service in 1936, the Swordfish looked somewhat out of place— even obsolete—in an age where monoplanes were the future. The new craft, however, was strong, easily handled, and could accurately deliver a torpedo. By the time World War II erupted in 1939, Swordfish equipped no less than 13 Fleet Air Arm squadrons.

Nobody in aviation circles could have anticipated what happened next, for the anachronistic

Stringbags emerged as one of the outstanding warplanes of aviation history. Commencing with action in Norwegian waters, Swordfish successfully directed naval gunfire and even scored the first U-boat sinking credited to the Fleet Air Arm. On November 11, 1940, 20 Swordfish made a surprise attack on the Italian fleet anchored at Taranto Harbor, severely damaging three battleships and sinking a host of lesser vessels. In May 1941, these aircraft also scored a damaging hit on the German superbattleship Bismark that resulted in its eventual destruction. Moreover, a handful of Swordfish operating out of Malta destroyed an average 50,000 tons of enemy shipping throughout most of 1942. These impressive tallies continued throughout the war. A new aircraft, the Fairey Albacore, arrived in 1942 to replace the old warrior, but it proved inferior in performance and popularity. The Swordfish was finally mustered out after 1945 with a production run of 2,391 machines. The Swordfish was a legendary warplane in every respect.

Type: Heavy Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 118 feet, 1 inch; length, 70 feet, 8 inches; height, 16 feet, 9 inches

Weights: empty, 23,122 pounds; gross, 39,242 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 860-horsepower Gnome-Rhone GR1Kbrs radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 199 miles per hour; ceiling, 26,250 feet; range, 1,240 miles

Armament: 3 x 7.5mm machine guns; 9,240 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1935-1944

|

T |

he ugly Farman F 222 was the largest French bomber of the interwar period. Its service was undistinguished, but the type mounted the first Allied air raid against Berlin.

The design concept for the Farman family of heavy bombers originated with a 1929 requirement calling for a five-seat aircraft to replace the obsolete LeO 20s. The prototype, designated the F 220, first flew in May 1932 and had all the trappings of a French bomber of this period. It was a high-wing monoplane with wings of considerable chord and thickness, braced by large struts canting inward toward the fuselage. The fuselage itself was very boxy and angular, sporting pronounced nose and dorsal turrets and a smaller ventral position. The four engines were mounted in tandem pods below the wing in pusher/tractor configuration and secured to the fuselage by means of a pair of small winglets. The overall effect was an unattractive, if capable, craft and, being entirely constructed from metal, a signal improvement over earlier bombers. With some re

finements it entered production as the F 221 in 1934 and was acquired in small batches. These represented the first four-engine bombers produced by the West at that time.

Looks aside, the Farman F 220 series was strong, reliable, and continually acquired in a series of updated models. The most important was the F 222 of 1938, which featured a redesigned nose section, dihedral on the outer wing sections, and retractable landing gear. However, the Farman aircraft were readily overtaken by aviation technology and rendered obsolete by 1939. They spent the first year of World War II dropping propaganda leaflets over Germany. After the Battle of France commenced in May 1940, several groups of Farman aircraft made numerous nighttime raids against industrial targets in Germany and Italy. It was a Navy F 223, the Jules Verne, that conducted the first Allied raid on Berlin that June. Many subsequently escaped to North Africa and were employed as transports by various regimes until

1944. Total production reached 45 units.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 95 feet, 7 inches; length, 46 feet, 3 inches; height, 17 feet, 6 inches Weights: empty, 7,900 pounds; gross, 10,978 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 345-horsepower Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII liquid-cooled in-line engines Performance: maximum speed, 95 miles per hour; ceiling, 9,600 feet; range, 700 miles Armament: 4 x.303-inch machine guns; 920 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1917-1927

|

T |

he F2A was a British-American hybrid design and highly effective as a patrol craft. Its career closely paralleled the Short Sunderland of a later date and firmly established the reputation of flying boats as weapons.

Commander John C. Porte of the Royal Navy was a longtime advocate of flying boats for naval service. In 1914 he ventured to the United States at the behest of aircraft builder Glenn Curtiss to work on American designs. Following the onset of World War I he returned home, firmly convinced that England could benefit by such craft. However, as commander of the Felixstowe station, he found Curtiss H.4s operating there unsatisfactory and set about modifying them. His subsequent F1 was found to be a better performer, so in 1917 he scaled up the new hull and fit it to the wings of a very large Curtiss H-12 Large America. The resulting hybrid was a superb aircraft for the time. It easily operated off the rough water conditions inherent in Northern Europe and, despite

its bulk, was relatively maneuverable once airborne. This new craft was christened the Felixstowe F2A, and it arrived in the spring of 1917 just as Germany’s infamous U-boat campaign was peaking.

The Felixstowe flying boat acquired a well – earned reputation as the best flying-boat design of the war. Heavily armed with bombs and machine guns, it destroyed submarines and Zeppelins on several occasions. Moreover, it could readily defend itself against the numerous German floatplane fighters encountered over the North Sea. This fact was underscored on June 4, 1918, when four F2As beat off an attack by 14 Hansa-Brandenburg W.29s, shooting down six with no loss to themselves. In an attempt to improve the Felixstowe’s performance, a new version, the F3, was developed. It featured longer wings and twice the bomb load but handled poorly and was never popular. The excellent F2As, meanwhile, remained on active duty for a decade following the war.

Type: Medium Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 70 feet, 9 inches; length, 52 feet, 9 inches; height, 15 feet, 7 inches Weights: empty, 14,770 pounds; gross, 22,046 pounds Power plant: 2 x 1,000-horsepower Fiat A.80 radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 264 miles per hour; ceiling, 22,145 feet; range, 1,710 miles Armament: 4 x 7.7mm machine guns; up to 3,527 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1936-1943

|

T |

he lumbering Cignona was the best-known Italian bomber of the 1930s and a potent symbol of fascist rearmament. Slow and poorly armed, it suffered heavy losses in World War II.

During the early 1930s, the fascist regime under Benito Mussolini strove mightily to acquire a first-rate air force for military as well as propaganda purposes. In 1935 the invasion of Ethiopia highlighted Italy’s great need for modern bombers. The following year, noted engineer Celestino Rosatelli conceived a new design that, at the time it appeared, was the most advanced in the world. The BR 20 was a low-wing, twin-engine monoplane featuring a metal framework fuselage and wings, twin rudders, and retractable undercarriage. The craft employed stressed skin throughout save for the aft fuselage, which retained a fabric covering. Given the name Cignona (Stork), it became operational in 1936, and several were dispatched to Spain to fight alongside Franco’s Nationalist forces. The BR 20s gave a good account of themselves, but glaring weaknesses in armament were addressed in subsequent versions. Cu

riously, Japan purchased 100 Cignonas to serve as an interim bomber until the Mitsubishi K 21 arrived. Their performance in China confirmed earlier deficiencies, and they were quickly phased out. In 1939 the BR 20M (Modificato) appeared and introduced a cleaned-up fuselage, broader wings, and heavier defensive armament. Several hundred were deployed by June 1940, when Italy declared war on France and Great Britain.

Despite its prior celebrity, the service record of the BR 20 in World War II was mediocre at best. Two groups were dispatched to Belgium that fall with the Corpo Aereo Italiano (the Italian air corps) and participated in latter phases of the Battle of Britain. They suffered heavy losses at the hands of Royal Air Force fighters and were withdrawn in weeks. BR 20s next fought in Greece, Malta, Yugoslavia, and North Africa and performed well when unopposed. Unfortunately, they remained vulnerable in the face of determined resistance. By 1943 only a handful remained in service. A total of 602 were constructed.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 31 feet, 1 inch; length, 24 feet, 5 inches; height, 8 feet, 7 inches Weights: empty, 3,086 pounds; gross, 4,343 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 800-horsepower Fiat RA bis (improved) liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 205 miles per hour; ceiling, 26,245 feet; range, 485 miles Armament: 2 x 12.5mm machine guns; 2 x 7.7mm machine guns Service dates: 1935-1941

|

T |

he Chirri was one of the finest biplane fighters ever designed. It proved so good that Italian aviators were reluctant to abandon such craft long after they had become obsolete elsewhere.

In 1932 Italian aircraft designer Celestino Rosatelli unveiled his CR 30, a defining moment in biplane evolution. As a fighter, the CR 30 was breathlessly acrobatic for its day, but Rosatelli was determined to wring out even better performance with continuing refinement. The ensuing CR 32 was a slightly smaller, cleaned-up version of the earlier craft and the most significant Italian fighter plane of the 1930s. Like its predecessor, the CR 32 was a metal-framed, fabric design with a distinctive chin – type radiator. The wings were strongly fastened by “W”-shaped Warren interplane struts and trusses throughout. Consequently, the CR 32 could literally be thrown about the sky and was capable of the most violent acrobatics. This rendered it superbly adapted as a dogfighter, a point well taken by Italian pilots. In 1936 CR 32s entered into service and by

1939 a total of 1,212 machines had been built in four versions.

The Chirri, as it became known, was instantly popular with fighter pilots around the world. The Chinese imported several and used them effectively against the Japanese in 1937. Hungary also bought them for its air force, but the most important customer was Spain. CR 32s were flown by both Spanish and Italians during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1938), and they proved formidable adversaries to the Russian-supplied Polikarpov I 15 biplanes and I 16 monoplanes. However, success carried a price. Because of their experience with the Chirri, Italians became so enamored of biplane dog – fighters that they continued producing them long after they were obsolete. By the time Italy entered World War II in 1940, the CR 32 and CR 42 biplanes constituted nearly 70 percent of Italian fighter strength. Nevertheless, some CR 32s were successfully employed in East Africa before assuming trainer functions in 1941.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 31 feet, 10 inches; length, 27 feet, 1 inch; height, 11 feet, 9 inches

Weights: empty, 3,929 pounds; gross, 5,060 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 840-horsepower Fiat A.74 RC.38 radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 267 miles per hour; ceiling, 33,465 feet; range, 482 miles Armament: 2 x 12.7mm machine guns Service dates: 1939-1945

|

T |

he superb-handling Falco (Falcon) was the last military biplane manufactured in quantity and the last to see wartime service. Despite obvious obsolescence, it was actively employed throughout World War II.

Celestino Rosatelli’s successful CR 32 biplane fighter prompted him to extend the life of the series with a newer version. This was undertaken at a time when most nations were discarding biplanes in favor of faster monoplane aircraft. Nevertheless, in 1939 Fiat unveiled the CR 42, possibly the finest expression of biplane technology ever constructed. Like the CR 32, the new craft consisted of metal frames and fabric covering. It was also the first Rosatelli design to use a radial engine, which was covered in a long chord cowling. The usual Warren struts were present, as were fixed, spatted landing gear. Unquestionably, the CR 42 continued Fiat’s tradition of robust fighters, being fast for a biplane, wonderfully acrobatic, and delightful to fly. The Regia Aeronautica (Italian air force) adopted it as its

last biplane fighter, and by 1940 the Falcos were a major service type. The prevailing prejudice against biplanes notwithstanding, CR 42s were also exported abroad to Belgium, Hungary, and Sweden.

The CR 42 was history’s last combat biplane, and it campaigned extensively throughout World War II. They were initially engaged in the defense of Belgium and, after Italian entry into the war by 1940, flew missions against southern France. A large number subsequently arrived in Belgium to participate in the Battle of Britain, where they took heavy losses and were withdrawn. In secondary theaters the Fal – cos had better success, and they fought well in the Greek campaign, over Crete, and against a host of obsolete British aircraft in East Africa.

CR 42s formed the bulk of Italian fighter strength throughout the North African campaign and, although failing as fighters, performed useful work in ground support. Only a handful survived the Italian surrender in 1943, and Germans operated them as night intruders in northern Italy until 1945.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 36 feet, 1 inch; length, 27 feet, 2 inches; height, 11 feet, 9 inches

Weights: empty, 4,442 pounds; gross, 5,511 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 840-horsepower Fiat A.74 RC.38 radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 302 miles per hour; ceiling, 35,269 feet; range, 621 miles Armament: 2 x 12.7mm machine guns Service dates: 1938-1943

|

T |

he much-maligned Freccia was Italy’s first allmetal monoplane fighter. Like many contemporaries, it was underpowered, underarmed, and outclassed by competing British and German designs.

By the mid-1930s Italy’s aircraft industry felt increasing pressure to develop new and more modern aircraft. In 1935 Giuseppe Gabrielli of Fiat conceived that country’s first all-metal monoplane fighter, the G 50 Freccia (Arrow). It was a midsized machine with a fully enclosed canopy, retractable landing gear, and rather appealing lines. However, it was powered by a bulky radial engine because suitable in-line power plants were unavailable. Tests successfully concluded by 1937, and the following year a preproduction batch of 12 machines was deployed to fight in the Spanish Civil War. There pilots enjoyed the G 50’s outstanding maneuverability but disliked the closed canopy, which impeded all-around vision. Subsequent models featured an open cockpit reminiscent of World War I-era fighters. The Freccia entered production in 1939 with the Regia Aeronautica (Italian air force), and several were also obtained by Finland. Production remained

slow, and when Italy entered World War II in June 1940, only 97 G 50s were on hand.

The decision to build the Freccia seems even more absurd in light of events that followed. As a fighting platform, it offered performance nowhere comparable to the Spitfire, Hurricane, or Me 109, being slower and underarmed. Accordingly, when the first G 50s were deployed in Belgium to fight in the Battle of Britain, most fighter pilots deliberately avoided combat against their better English counterparts. In September 1940 the G 50 bis (improved) appeared, featuring increased fuel capacity, a redesigned tail, and glazed cockpit side panels but otherwise little enhancement of performance. Others were fitted with bomb racks and fulfilled ground-attack missions. Freccias fought throughout the Greek and North African campaigns with mediocre results and were largely discarded following the September 1943 Italian surrender. Curiously, in Finnish hands the aging fighters did valuable work against Soviet forces and remained in frontline service until 1947! A total of 774 Freccias were built.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 29 feet, 6 inches; length, 38 feet, 3 inches; height, 14 feet, 6 inches

Weights: empty, 8,117 pounds; gross, 17,196 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 2,725-pound thrust General Electric J85 turbojet engines

Performance: maximum speed, 690 miles per hour; ceiling, 41,000 feet; range, 740 miles

Armament: 2 x 30mm cannons; up to 4,000 pounds of bombs or rockets

Service dates: 1959-1998

|

T |

he G 91 was the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s first attempt to build and deploy a standard warplane for use by member nations. Small and easy to operate, it served as a frontline strike fighter for many years.

In 1954 NATO announced competition for a modern tactical strike aircraft. The new machine had to be fast, well-armed, and capable of operating off short, unprepared landing strips. Moreover, it was to be built and deployed by NATO member nations in an attempt to standardize equipment and capabilities. In 1956 a Fiat design team headed by Giuseppe Gabrielli unveiled the prototype G 91, which bore strong resemblance to the larger F-86Ks then built under license. It was modestly sized with swept wings, tricycle gear, and a spacious bubble canopy. In flight the G 91 was light, responsive, and could carry a variety of weapons. Evaluation trials held in 1957 demonstrated that it was superior to several French contenders, so the decision was

made to adopt the craft for German and Italian forces. France angrily refused to have anything to do with the diminutive craft, but 756 G 91s were ultimately produced. For Germany, G 91s were the first fighters manufactured in that country since 1945. Moreover, whatever G 91s lacked as dogfighters, they more than compensated for as strike aircraft.

By 1965 the original G 91 design had grown somewhat long in the tooth, so an updated version was proposed. This was the G 91Y, or Yankee, which differed from earlier models by having two General Electric engines instead of the single Orpheus turbojet. The result was nearly 60 percent more thrust and very little additional weight. The G 91Y was a far more capable attack craft and could carry all the latest NATO ordnance, including nuclear weapons. A total of 75 were built for the Italian air force, and they were widely employed in their intended role until 1998. The German machines had been retired a decade earlier by the Dassault/Dornier Alphajet.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 46 feet, 9 inches; length, 32 feet, 5 inches; height, 9 feet, 10 inches Weights: empty, 2,500 pounds; gross, 2,910 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 240-horsepower Argus As 10C liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 109 miles per hour; ceiling, 17,060 feet; range, 205 miles Armament: 1 x 7.92mm machine gun Service dates: 1937-1945

|

T |

he ungainly Storch was one of the earliest STOL (short takeoff and landing) airplanes. It served in large numbers across Europe and Africa wherever the German army fought.

In 1935 the German Air Ministry announced competition for an army cooperation aircraft, one specifically designed to operate from very confined areas. A prototype entered by Fieseler beat out two airplanes and a helicopter to win the contest in 1936. The Fi 156 was a high-wing, cabin monoplane with exceptionally long undercarriage to kept the nose highly elevated. It was conventionally constructed of steel tube, wood, and fabric covering. The wing surfaces were also braced and the cabin extensively glazed to afford the crew of two excellent vision. But the secret of the Storch (Stork) lay in the configuration of its main wing. The front portion sported full-span Handley Page wing slats while the trailing edge had slotted flaps and ailerons. Fully deployed, this arrangement allowed the diminutive craft to lift off in only 200 feet. Army officials were very im

pressed with the Fi 156 and in 1937 production commenced. By 1945 a total of 2,834 had been built.

In service the Storch acquired a legendary reputation for its uncanny ability to operate where most aircraft could not. The slow-flying craft could even hover motionless while flying into a gentle headwind! This made it an ideal army cooperation craft, and hundreds were deployed with military units from the frozen fringes of the Arctic to the burning sands of North Africa. Storches were also widely employed to serve as medevac, liaison, reconnaissance, and staff transport. Moreover, Field Marshals Erwin Rommel and Albert Kesselring employed Fi 156s as personal transports throughout campaigns in North Africa and Italy. Perhaps its most notorious episode was in helping rescue Benito Mussolini from his mountainous prison in September 1943. Two years later, noted avia – trix Hanna Reitsch flew one of the Storch’s last missions by touching down in the ruins of Berlin with General Robert Ritter von Greim, newly appointed head of the nearly defunct Luftwaffe.