. Antonov An 124 Ruslan

Dimensions: wingspan, 240 feet, 5 inches; length, 226 feet, 8 inches; height, 68 feet, 2 inches

Weights: empty, 385,800 pounds; gross, 892,875 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 51,590-pound thrust Lotarev D-18T turbofan engines

Performance: maximum speed, 537 miles per hour; range, 10,523 miles

Armament: none

Service dates: 1987-

|

I |

n 1985 the mighty Ruslan edged out Lockheed’s C-5A to become the biggest airplane to achieve production status. Three years later it was surpassed by an even larger derivative, the An 225.

In 1968 the U. S. Air Force’s acquisition of the giant C-5A Galaxy gave it unparalleled ability to ship military hardware anywhere on the globe. The Soviet Union needed similar capacities to keep pace with the West, so in 1974 the Antonov design bureau was instructed to cease production of the huge An 22 turboprop transport and commenced designing a jet-powered craft. The specifications established for the An 124 were mind-boggling: It had to carry a minimum cargo of 150 tons to any point within the Soviet empire without refueling. Antonov, drawing inspiration from previous designs and the C-5A, fielded a prototype in 1985. The new An 124 was 18 feet wider than the vaunted Galaxy, and it also possessed 53 percent greater hauling capacity. Like its competitor, which it greatly resembles, the Ruslan (named after Puskin’s legendary giant) has nose and

tail cargo doors that allow vehicles to drive on and off. The spacious cargo hold is lined by a special titanium floor equipped with rollers, and roof- mounted hydraulic winches facilitate cargo-handling. It also has a pressurized passenger cabin for 88 people. Moreover, the giant craft can be made to “kneel” while unloading through retractable nose – wheels. Since 1987 an estimated 48 An 124s have been built, with half going to the air force and the remainder operated by the state airline Aeroflot. The NATO designation is CONDOR.

The reign of the An 124 was exceedingly short, for in 1988 it yielded the throne to an even bigger derivative, the An 225 Mriya (Dream). This is essentially a stretched Ruslan fitted with six turbofans that expel a combined total of 309,540 pounds of thrust! It was expressly designed to freight heavy components for the Russian space program, carrying large items like the space shuttle Buran piggyback. Only two of these giants have been built, and they remain the largest aircraft in world history.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 36 feet, 1 inch; length, 31 feet, 2 inches; height, 10 feet, 9 inches Weights: empty, 4,057 pounds; gross, 5,457 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 690-horsepower Junkers Jumo 210 Da liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 190 miles per hour; ceiling, 26,575 feet; range, 258 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns Service dates: 1936-1940

|

T |

he Arado Ar 68 was the last biplane fighter of the German Luftwaffe. A capable performer, it briefly fulfilled a variety of duties, including training and nighttime fighting.

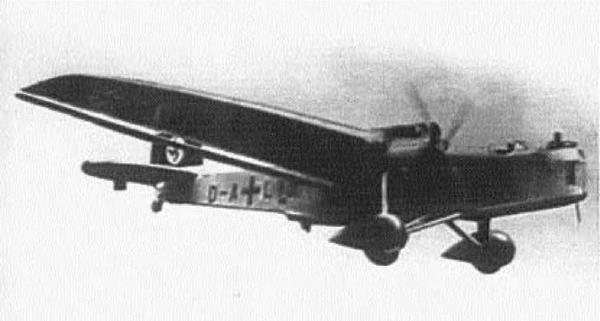

By the terms of the 1918 Armistice, Germany was forbidden to possess military aircraft of any kind. But even before the Nazi era commenced, the German war ministry began secretly developing warplanes in collusion with the Soviet Union. By 1933 the newly elected Nazi regime under Adolf Hitler scoffed at these treaty provisions and encouraged Arado to develop a new fighter to replace the unpopular Heinkel He 51. Arado had previously acquired much experience in Russia, so in 1935 it fielded the first prototype Ar 68. This was a singlebay biplane with an oval-section fuselage made of metal. The wings were constructed of wood and were fabric-covered. A distinctive feature was the rather high, thin rudder, which subsequently became an Arado trademark. Results were initially disappointing, and subsequent prototypes experimented with a variety of power plants. By 1936 a 750-horse-

power BMW Vi-powered Ar 86 was regarded as ready and commenced flight trials against the He 51. The Luftwaffe high command was reluctant to acquire another biplane, seeing how the monoplane Messerschmitt Bf 109 was on the verge of production. However, in the hands of Ernst Udet, the Ar 68 easily outflew its opponent, and the type entered production in 1937.

The Ar 68 was an efficient design, fast and forgiving, but also obsolete at the inception of its career. it flew well during test trials in Spain, but the Bf 109, also present, consistently outperformed it. Consequently, the type was acquired only in small numbers before the Messerschmitt emerged as the Luftwaffe’s standard fighter. By the onset of World War II in 1939, most Ar 68s were functioning as advanced trainers. A naval version, the radial-engine Ar 167, was developed for possible deployment on the carrier Graf Zeppelin, but the project was scrapped. After brief service as emergency night fighters in 1940, all surviving Ar 68s were unceremoniously retired.

Type: Trainer

Dimensions: wingspan, 36 feet, 1 inch; length, 27 feet, 1 inch; height, 8 feet, 8 inches Weights: empty, 2,854 pounds; gross, 3,858 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 485-horsepower Argus As 410MA-1 liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 211 miles per hour; ceiling, 22,965 feet; range, 615 miles Armament: 1 x 7.92mm machine gun Service dates: 1940-1945

|

T |

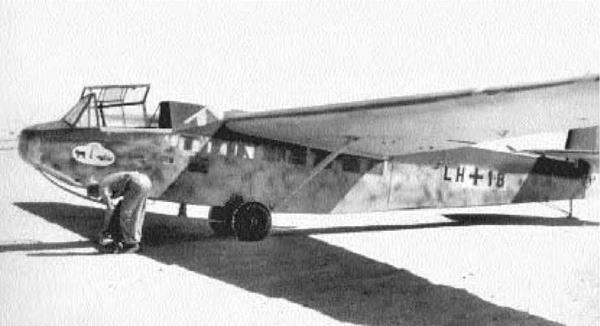

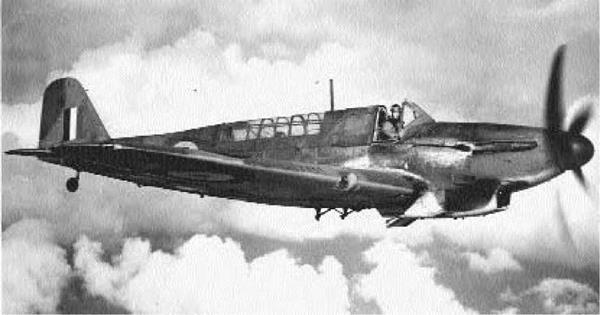

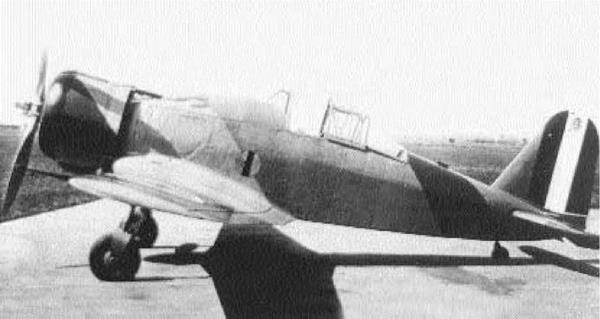

he Ar 96 was the Luftwaffe’s most significant advanced trainer, for it instructed virtually all German pilots of World War II. It was built in greater number than any training craft of the period, save for the North American AT-6.

The Ar 96 was designed by Walter Blume in 1938 as a new advanced trainer for the Luftwaffe. It was a streamlined, low-wing monoplane constructed entirely of metal and stressed skin. Student and instructor were housed in tandem seats under a highly glazed canopy. The fuselage was oval-sectioned and mono – coque in design, topped by a trademark Arado tail fin. The new craft was a delightful performer, with a 240- horsepower Argus As 10C in-line engine and a fixed, two-blade propeller. However, the undercarriage, which originally retracted outward toward the wings was totally redesigned. An inward, widetrack retracting system was subsequently adopted as better suited for rough student landings. The Ar 96 entered production in 1940, and over the next five years it was a common sight at Luftwaffe training schools.

In 1940 the Ar 96B prototype emerged. This differed from earlier models by having a more powerful Argus AS 410A engine, as well as a lengthened fuselage housing more fuel. It also featured a distinct, variable-pitch propeller spinner and a 7.9mm machine gun for gunnery training. This variant was built in large numbers throughout the war years by Arado, Ago, and the former Czech factories of Avia and Letov. By 1945 no less than 11,546 Ar 96s had rolled off the assembly lines. It constituted the mainstay of the Luftwaffe’s advanced training force and, as such, bore a conspicuous role in the overall excellence of that force. Toward the end of the war, several Ar 96Bs were impressed into field service with machine guns and bombs for ground-attack purposes. Afterward, the type was continued in production by the French concern SIPA, which built a wooden version in 1946, followed by an all-metal one. Similar craft were also manufactured in Czechoslovakia until 1948.

Type: Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 40 feet, 8 inches; length, 36 feet, 1 inch; height, 14 feet, 4 inches Weights: empty, 6,580 pounds; gross, 8,223 pounds Power plant: 1 x 960-horsepower BMW 132K radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 193 miles per hour; ceiling, 23,000 feet; range, 670 miles Armament: 3 x 7.92mm machine guns; 2 x 20mm cannons; 220 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1939-1945

|

F |

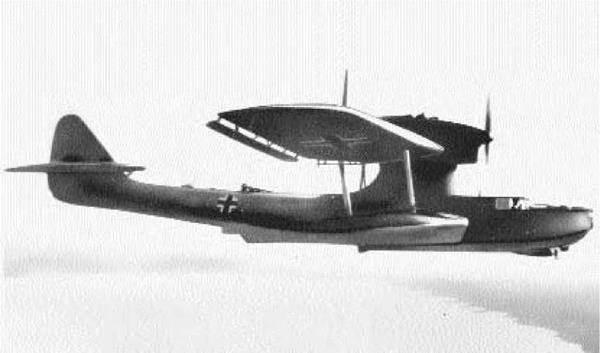

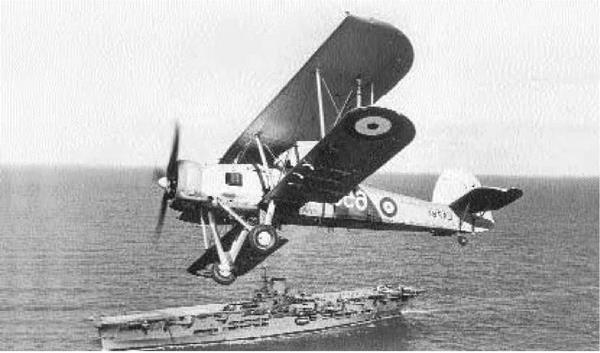

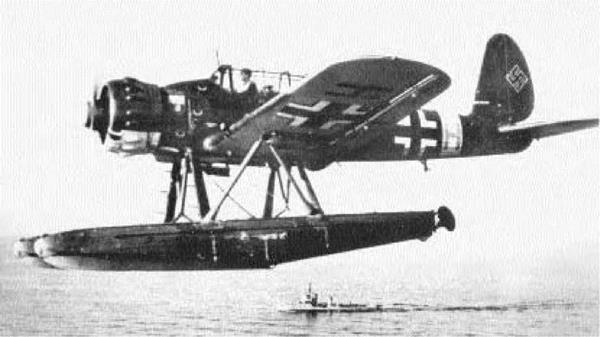

rom Norway to the Mediterranean, the versatile Ar 196 served as the “eyes” of the German Kriegsmarine. Fast, well-armed, and solidly built, they were the best floatplanes of their class during World War II.

By 1936 it was envisioned that the newly reconstituted Kriegsmarine (German navy) was destined to serve as fast, hard-hitting commerce raiders. Because this required efficient aerial reconnaissance, the German Air Ministry issued specifications for a new floatplane to accompany all German capital ships. In 1937 Arado perfected its prototype Ar 196 floatplane to compete with a design proffered by Focke-Wulf, the Fw 62. Arado’s craft was a radial – engine, low-wing monoplane with twin floats. It was of all-metal construction and stressed skin, save for the rear fuselage, which was fabric-covered. The trailing edges of the rounded wings were filled entirely with flaps and ailerons. Once fitted with a variable-pitch, three-blade propeller, the Ar 196 easily outperformed its rival and entered service in 1939. In time, it ultimately outfitted air units on board the

major warships Bismark, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Prinz Eugen, Admiral Scheer, Graf Spee, and Lut – zow.

In service the Ar 196 proved to be among the most capable floatplanes of the war, one of few designs to serve outside the Pacific. Moreover, it exhibited better performance than contemporary British and U. S. machines like the Fairey Sea Fox and Curtiss Seagull. As spotting aircraft, Ar 196s would shadow enemy vessels and relay intercept coordinates back to their home ships. Those not stationed on warships flew from bases ringing the Bay of Biscay and the Mediterranean. And despite their floatplane configuration, they were well-armed and could put up a fight. On May 5, 1940, two Ar 196s under Lieutenant Gunther Mehrens spotted the damaged British submarine HMS Seal off Denmark and forced its surrender. Other Ar 196s provided escort duty for Axis convoys and occasionally shot up British patrol aircraft with their heavy armament. Ar 196s served in dwindling numbers until the war’s end. A total of 593 were built.

Type: Reconnaissance; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 46 feet, 3 inches; length, 41 feet, 5 inches; height, 14 feet, 1 inch

Weights: empty, 11,464 pounds; gross, 21,715 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 1,980-pound thrust Junkers Jumo 004B turbojet engines

Performance: maximum speed, 460 miles per hour; ceiling, 32,810 feet; range, 684 miles

Armament: 2 x 20mm cannons; 3,307 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1944-1945

|

T |

he beautiful Blitz was the world’s first operational jet bomber. Appearing too late to affect events in World War II, it served as a technological precursor of things to come.

In 1940 the German Air Ministry laid down specifications for a fast reconnaissance craft powered by the new Junker Jumo jet engines, then undergoing bench tests. The Arado design team, headed by Walter Blume and Hans Rebeski, came up with an extremely handsome machine. The Ar 234 was a high-wing monoplane made entirely of metal. The pilot sat up front in a fully glazed nose section, and two podded jet engines were mounted under straight wings. To reduce drag, the fuselage was deliberately kept as narrow as possible, although this initially precluded the use of landing gear. In fact, the first six prototypes were fitted with detachable trolleys that fell away upon takeoff, leaving the craft to land on skids. Commencing with the seventh prototype, all subsequent Ar 234s received narrow- track landing gear. In flight the Ar 234 was extremely

fast and quite maneuverable; it also pioneered such novel technology as pressurized cabins, ejection seats, autopilots, and bombing computers. With the Nazi regime fading fast by 1944, the Ar 234 received priority production status, and 274 machines were assembled.

The Blitz commenced operational sorties over England in the fall of 1944, where its high speed rendered it immune from Allied interception. Given such good performance, it was decided to introduce a bomber version, the Ar 234 B-2, which carried bombs on its fuselage and engine pods. These were the world’s first operational jet bombers. Their most celebrated action occurred in January 1945, when waves of Ar 234s hit the Remagen Bridge over the Rhine, collapsing it. The Blitz continued its little war of unstoppable pinprick raids until the last few weeks of the war, when jet fuel became unavailable. Had this amazing airplane been available in quantity, serious damage might have resulted. It nonetheless demonstrated the viability of jet bomber technology.

Type: Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 43 feet, 6 inches; length, 31 feet, 5 inches; height, 10 feet, 11 inches Weights: empty, 1,916 pounds; gross, 2,811 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 160-horsepower Beardmore liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 95 miles per hour; ceiling, 13,000 feet; range, 250 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns Service dates: 1917-1918

|

T |

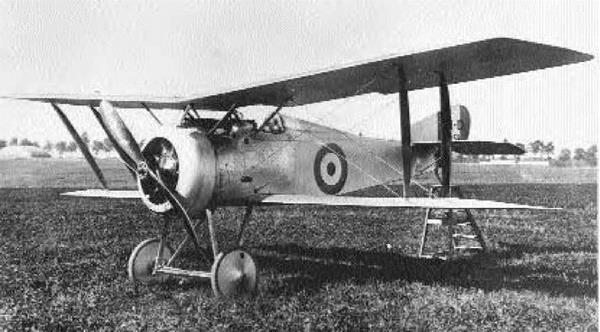

he FK 8 was one of the most numerous British observation aircraft of World War I. Fast, strong, and well-armed, it went by the chummy but unflattering appellation of “Big Ack.”

In 1914 Dutch aircraft designer Fredrick Kool – hoven submitted plans to the British air minister to replace its antiquated BE 2c with a more capable machine. The design was entrusted to the firm Armstrong-Whitworth, and in 1915 the FK 3 emerged. More than 500 of these machines, informally dubbed “Little Ack,” were constructed and equipped several squadrons in the Middle East. The following year Koolhoven suggested an upgraded version based upon the previous machine, and thus was born the FK 8. This was a standard biplane with two bay wings, the top of which exhibited pronounced dihedral. The crew of two sat in a deep fuselage constructed from wood and fabric. One interesting feature was the presence of controls in both cockpits so that a gunner could fly the plane if the pilot became

incapacitated. Early FK 8s were also fitted with an ugly central skid on the landing struts to prevent noseovers. Around 1,500 were manufactured.

In combat the “Big Ack” was a rugged machine and capable of defending itself. Although not speedy, it maneuvered well, absorbed great amounts of damage, and was considered superior to the contemporary Royal Aircraft Factory RE 8. One incident illustrates the combat career of the FK 8 above all others when, on March 27, 1918, Lieutenants Macleon and Hammond were jumped by eight of the formidable Fokker triplanes. In a running battle, the FK 8 managed to shoot down four of its opponents, even while burning and badly shot up. The two men survived a crash landing and subsequently received the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest honor. The FK 8s were retired immediately after the war, but eight ended up in Australia. There they helped form the nucleus of the Northern Territory Aerial Services, better known today as QUANTAS.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 33 feet, 2 inches; length, 25 feet, 4 inches; height, 10 feet, 2 inches Weights: empty, 2,061 pounds; gross, 3,012 pounds

Power plant: 1 450-horsepower Armstrong-Siddeley Jaguar IV radial engine Performance: maximum speed, 156 miles per hour; ceiling, 27,000 feet; range, 150 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns Service dates: 1927-1932

|

T |

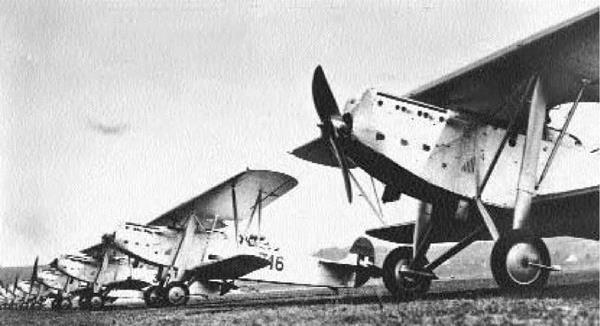

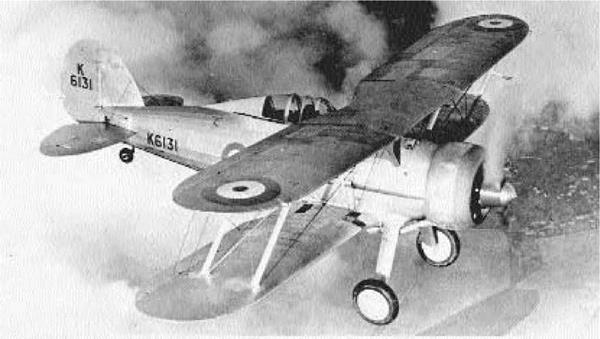

he Siskin was Britain’s first post-World War I fighter and the first to possess an all-metal structure. It was phenomenally maneuverable and standard fare at air shows for many years.

Britain, although victorious in World War I, was beset by extreme economic hardship during the postwar period. Consequently, it was unable to procure new fighter craft for the Royal Air Force until 1924. That year the Royal Air Ministry authorized two models into production, the Gloster Grebe and the Armstrong-Whitworth Siskin. The latter originated in a company aircraft of the same name that had first been designed in 1918. This was a standard, wood-constructed biplane in most respects, save for being powered by an ABC Dragon radial engine. A fine performer, it was subsequently refitted with a 200-horsepower Armstrong-Siddeley Jaguar radial, and it went on to win the 1923 King’s Cup Air Race with speeds of 149 miles per hour. The new prototype, christened the Siskin III, differed from its predecessor in several respects. First, both wing and

fuselage frames were constructed of metal and were fabric-covered. As a sesquiplane, the upper wings were longer than the lower ones. The new craft was also the first British biplane to utilize vee interplane struts between the wings. In service the Siskin was a smart performer with outstanding maneuverability. A total of 62 machines were built in 1926, supplanting aging Sopwith Snipes in two squadrons.

In 1927 a definitive variant, the Siskin IIIA, emerged. This version lacked both an auxiliary fin beneath the rear fuselage and the dihedral on the upper wing. Moreover, it was powered by the 450- horsepower Jaguar IVS engine, which endowed it with even greater performance. A total of 385 Siskin IIIAs were acquired, and they outfitted 11 fighter squadrons. Their handling was so outstanding that they frequently starred at the yearly Hendon Displays. There No. 43 Squadron pioneered formation acrobatics and featured stunts with several aircraft tied together. The fine-flying Siskins were eventually phased out in 1932 by Bristol Bulldogs.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 84 feet; length, 69 feet, 3 inches; height, 15 feet Weights: empty, 19,330 pounds; gross, 33,500 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 1,145-horsepower Rolls-Royce Merlin X liquid-cooled in-line engines Performance: maximum speed, 222 miles per hour; ceiling, 17,600 feet; range, 1,650 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 7,000 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1937-1945

|

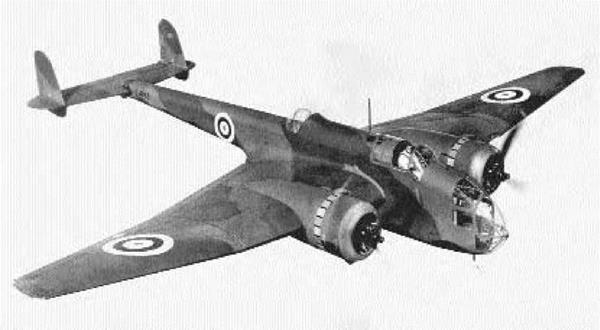

T |

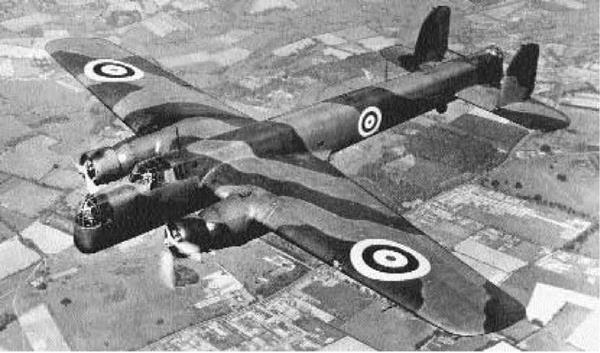

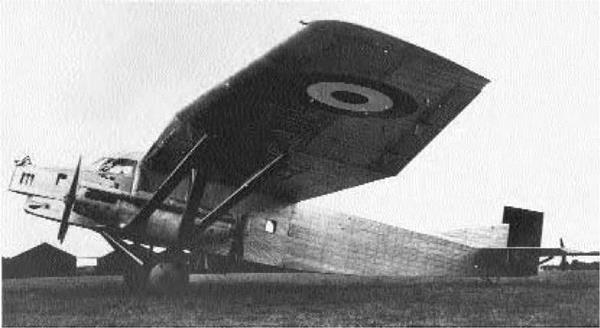

he rugged Whitley was the principal British bomber during the early days of World War II. It was the first British aircraft to drop bombs on German soil since 1918 and saw extensive use up through the end of the war.

In 1935 Air Ministry Specification B.3/34 mandated replacing the aging Handley Page Heyfords with a more modern design. Armstrong-Whitworth responded with what would become its most numerous aircraft. The Whitley was a midwing monoplane whose construction was midway between contemporary designs and those of World War II. Constructed of metal, it possessed twin rudders, and sported a retractable undercarriage. The slab-sided fuselage was also sheeted with flushed metal skin, but the thick wing lacked dihedral and the ailerons were fabric-covered. The Whitley performed well in test flights, and its drooping nose gave it a distinct, jut-jawed appearance. The Royal Air Force decided to place orders in 1936, and the following year Whitleys began equipping various bomber squadrons. Subsequent versions were fitted with more power

ful, in-line engines, and others were outfitted with radar and employed by the RAF Coastal Command. Production ran to 1,184 machines.

When World War II commenced in September 1939, Whitleys comprised the mainstay of RAF Bomber Command’s frontline strength. It was marginally obsolete and overshadowed by the more modern Wellingtons and Hampdens, but in service it accomplished a number of aviation firsts. After spending the first year dropping leaflets over Germany, in August 1940 Whitleys became the first British aircraft to drop bombs on Berlin since World War I. The following February, they bombed the Tragino viaduct after Italy’s declaration of war against Britain, the first such action against that country. Numerous Whitleys were then rigged for parachute operations, and in February 1942 the German radar installation at Bruneval was raided. They also sank their first U-boat in the Bay of Biscay on November 30, 1941. These unattractive, rugged aircraft finally performed training and patrolling activities up through the end of hostilities. The Whitley was a capable, underappreciated aircraft.

|

|

|||

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 30 feet, 10 inches; length, 26 feet, 10 inches; height, 9 feet, 2 inches Weights: empty, 3,218 pounds; loaded, 4,365 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 850-horsepower Hispano-Suiza 12Ydrs liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 245 miles per hour; ceiling, 34,875 feet; range, 360 miles Armament: 4 x 7.92mm machine guns Service dates: 1934-1944

|

T |

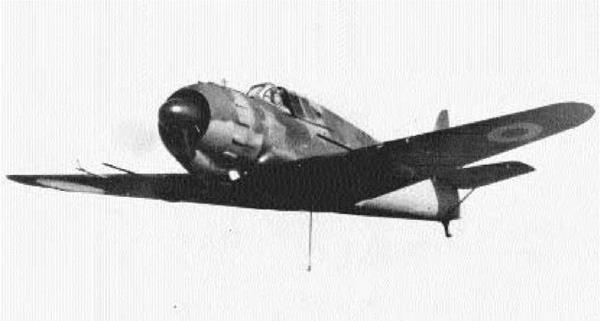

he beautiful Avia B 534 epitomized the very best of biplane technology. Although fast and maneuverable, it could not compete with modern monoplane fighters under development.

In 1932 the Avia firm under designer Frantisek Novotny substantially revised and updated its B 34 biplane fighter. Within a year a prototype emerged as the B 534, a machine as elegant in appearance as it was splendid in performance. Structurally, the B 534 was a single-bay biplane with wings of unequal length and highly staggered. Ailerons were placed on both the upper and lower wings to enhance maneuverability, while the whole craft was made of steel spars covered in fabric. The fuselage was streamlined and fitted with a beautifully wrought, close-fitting engine cowling. Moreover, it was heavily armed, mounting four machine guns. Two of these were originally wing-mounted, but when trials revealed unacceptable vibration when fired, they were relocated to the fuselage. The prototype was also fitted with a traditional open canopy, but subsequent production models were fully enclosed. Suf

fice it to say that the Czechoslovakian Army Air Force now possessed the fastest, most maneuverable biplane fighter on the continent.

The B 534 was delightful to fly, fast, and responsive to controls. At the 1937 Zurich International Flying Meet, it dominated all events and categories until pitted against Germany’s landmark monoplane fighter, the Messerschmitt Bf 109. Against this new breed of warrior, the Avia finished a close second, but the eclipse of biplane fighters was at hand. These craft might have put up tremendous resistance in 1938 when the Germans occupied western Czechoslovakia, but events transpired without a shot. A total of 446 Avia B 534s thus passed into German hands, and they were employed by the Luftwaffe as trainers and target tugs. Others were also similarly accorded to the puppet Slovak Air Force, which accompanied Hitler’s 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union. Indifferently flown by unsympathetic pilots, they failed to distinguish themselves. A handful of B 534s eventually flew against Germany during the Slovak revolt of 1944.

![]() Austria-Hungary/Germany

Austria-Hungary/Germany

Type: Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 27 feet; length, 22 feet; height, 7 feet, 6 inches

Weights: empty, 1,440 pounds; gross, 2,152 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 160-horsepower Mercedes liquid-cooled engine

Performance: maximum speed, 111 miles per hour; ceiling, 8, 200 feet; range, 280 miles

Armament: 1 x 7.62mm machine gun; 40 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1914-1918

|

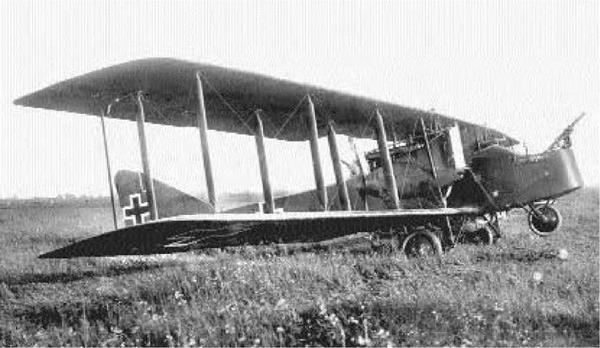

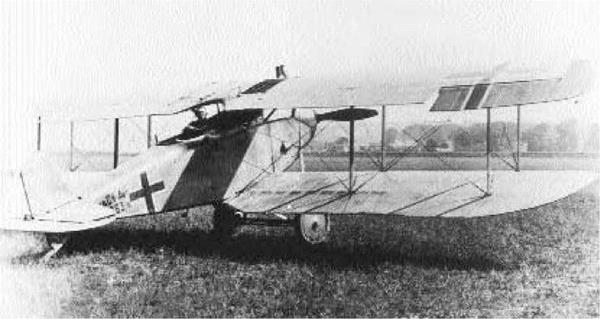

T |

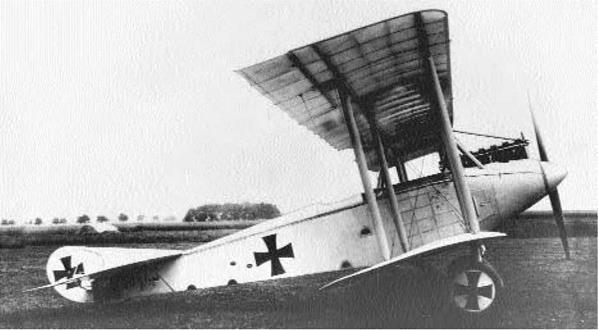

he Aviatik series was mediocre and quickly withdrawn from the Western Front during World War

I. However, the long range and dependability of these aircraft enabled them to serve in secondary theaters with distinction.

Following the onset of hostilities in August 1914, the Automobil und Aviatik AG company of Leipzig, Germany, commenced production of two – seat reconnaissance machines based upon its prewar P.15A models. An Austrian subsidiary, Osterreichis – che-Ungarische Flugzeugfabrik Aviatik of Vienna, also brought out slightly modified forms of the same craft. The first series, known as the Aviatik B I, was a conventional, fabric-covered, two-bay biplane with a slightly longer upper span. These craft were unusual in having the pilot placed in the rear seat while the gunner occupied the front. This seemingly absurd arrangement appreciably interfered with the latter’s field of fire while also obstructing the pilot’s view. Nonetheless, in the early days of aerial conflict, the long range and pleasant flying characteristics of the Aviatik made it popular with crews. It was also one

of the few two-seaters that could be rigged with bombs for harassment raids. Two subsequent versions, the B II and B III were introduced with more powerful engines and more conventional seating. These machines could fly nearly half again as fast and as high as the first model, but by 1916 they suffered heavily at the hands of improved Allied fighters. Moreover, they were aerodynamically less stable than earlier versions. The Germans eventually deemed them unacceptable for the Western Front.

In an attempt to upgrade the performance of Austrian aircraft, a new version, the C I, was introduced in 1915. Modifications included a new 160- horsepower Mercedes engine, an exhaust stack piped over the top wing, and a streamlined spinner. However, this model reverted back to the awkward arrangement of placing the pilot in the rear seat, a feature corrected again in the subsequent C III model. For want of a better replacement, they remained in Austrian service on the Italian and Russian fronts up through the end of the war. A total of 167 C models were constructed.

![]() Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: 26 feet, 3 inches; length, 22 feet, 9 inches; height, 8 feet, 1 inch

Weights: empty, 1,345 pounds; gross, 1,878 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 200-horsepower Daimler liquid-cooled in-line engine

Performance: maximum speed, 115 miles per hour; ceiling, 20,177 feet; range, 250 miles

Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns

Service dates: 1917-1918

|

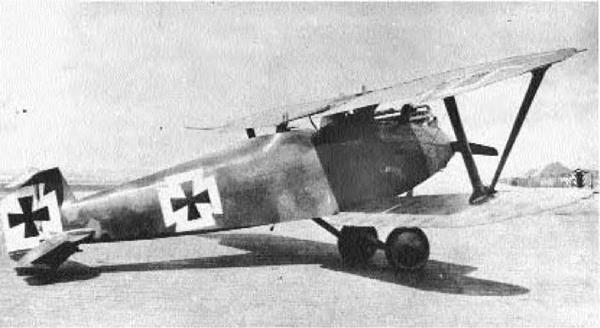

T |

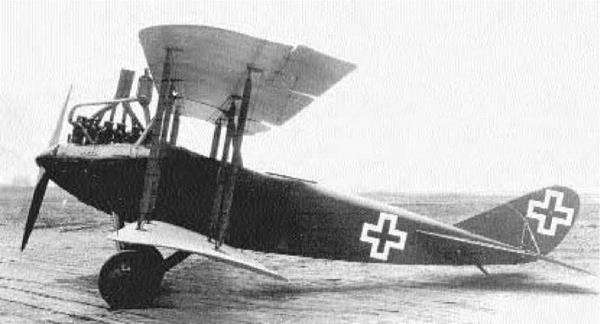

he “Berg Scout” was the first fighter designed and mass-produced in Austria. Although fastclimbing and maneuverable, it was distrusted by pilots because of a reputation for frailty.

In the fall of 1916, the Osterreichische-Un – garische Flugzeugfabrik Aviatik of Vienna began constructing a single-seat version of its two-seater C I machine. The chief designer, Julius von Berg, incorporated many features of the previous model into the new craft, which became known as the “Berg Scout.” The D I was a conventional biplane fighter with slightly staggered, single-bay wings. However, the fuselage was very deep, leaving only the pilot’s head exposed. This provided considerable shelter against the elements but interfered with forward vision. Worse yet, the D I was armed with a single machine gun mounted on the top wing that fired above the propeller arc at an angle. Thus situated, pilots enjoyed clear shots only while diving upon a target. However, the D I was light and, propelled by a 185-horsepower Daimler motor, climbed like a rocket. It entered production in the spring of

1917 and joined the ranks of the hard-pressed Luft – fahrtruppe (Austrian air service) that fall.

In service many pilots expressed displeasure with the D I’s performance. Flight tests demonstrated that it could outclimb and outturn the Austrian-built Albatros (Oef) D III with ease, but several machines crashed after structural wing failures. Moreover, the new 200-horsepower Daimler engines were powerful but prone to overheating. An entire series of experimental radiators was eventually fitted, but these only further obstructed the already cramped front view. In an attempt to up-gun the D I, a pair of machine guns was also fitted with interrupter gear that fired through the propeller arc, but these were placed so far forward that pilots could not unjam them by hand. Despite long-standing deficiencies in the machine, Austrian pilots eventually adapted to the “Berg Scout,” and it rendered respectable service against a host of Italian and Russian aircraft. Production orders totaled 1,200 aircraft, but only 700 had been delivered by the time of the Armistice.

Type: Reconnaissance; Light Bomber; Fighter; Trainer

Dimensions: wingspan, 36 feet; length, 29 feet, 5 inches; height, 10 feet, 5 inches Weights: empty, 1,240 pounds; gross, 1,800 pounds Power plant: 1 x 100-horsepower Gnome Monosoupape rotary engine Performance: maximum speed, 82 miles per hour; ceiling, 10,000 feet; range, 250 miles Armament: usually none, or 1 x.303-inch machine gun; up to 80 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1913-1933

|

T |

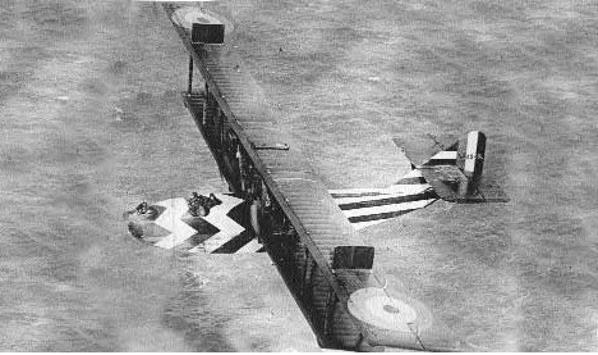

he gangly Avro 504 rates as one of the greatest airplanes ever. In a career spanning two decades it underwent many modifications and trained generations of pilots.

In 1913 Alliot Verdon Roe, a pioneer of tractor – propelled airplanes, demonstrated his latest creation, a rather modest-looking craft called the Avro 504. It was a standard two-seater biplane with four – bay wings and a large skid protruding from its landing gear. It was also immensely strong and exhibited docile handling qualities once airborne. Both the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Navy ordered several copies on the eve of World War I. Not surprisingly, Avro 504s were among the many reconnaissance aircraft dispatched to France, and on August 22, 1914, one received the dubious distinction of becoming the first British airplane lost in combat. The Royal Navy, fortunately, had outfitted their 504s as light bombers, and on November 21, 1914, four of the little biplanes launched a daring and devastating

raid upon the Zeppelin hangars at Friedrichshafen. During the course of the war, this handy craft received several modifications and one, the K version, was a single-seat fighter employed by home defense units until 1918!

However, it was as a trainer that the Avro 504 found its niche in aviation history. Commencing with the J model of 1916, it trained thousands of British and Allied pilots, including Prince Albert, the future King George VI. Moreover, it was the machine of choice at the famous School of Special Flying at Gosport. There the famous Major R. R. Smith-Barry used 504s to initiate his new and standardized system of flight instruction. After the war, it remained in production up through 1927 and was fitted with a bewildering variety of power plants. A total of 8,970 Avro 504s were built in England, with another 2,000 constructed in the Soviet Union. These remained in frontline service with the Royal Air Force until 1933 and flew many years thereafter with private owners.

Type: Reconnaissance; Trainer

Dimensions: wingspan, 56 feet, 6 inches; length, 42 feet, 3 inches; height, 13 feet, 1 inch

Weights: empty, 5,375 pounds; gross, 9,900 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 420-horsepower Cheetah XV radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 188 miles per hour; ceiling, 19,200 feet; range, 700 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 360 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1936-1968

|

T |

he venerable Anson was one of the longest-serving types in Royal Air Force history. Ease of flying and great reliability garnered it the nickname “Faithful Annie.”

In 1935 the British Air Ministry invited Avro to develop a twin-engine landplane for reconnaissance purposes. Avro drew upon its Model 652 commercial craft, two of which were sold to Imperial Airways in 1933. The prototype Anson was based upon this aircraft and first flew in 1935. It was a low-wing monoplane of mixed steel-tube, wood, and fabric construction. The fuselage was long and rectangular and sported a conspicuous dorsal gun turret. Having successfully concluded flight tests, Ansons entered service with the RAF in 1936. They were significant in being the first monoplane types accepted into service, and the first British warplane with retractable (if hand-cranked) landing gear. By the advent of World War II in 1939, Ansons equipped no less than 12 squadrons with the RAF Coastal Command. Its all-around utility and docile handling prompted the nickname “Faithful Annie.”

The Anson was marginally obsolete at the commencement of hostilities yet gave a good account of itself before being replaced by Armstrong – Whitworth Whitleys and Lockheed Hudsons. Only two days after the declaration of war in September 1939, one dropped bombs on a U-boat, the first offensive action taken by a Coastal Command aircraft. In June 1940 a trio of Ansons was jumped by nine formidable Bf 109 fighters; the little cluster not only beat off the assailants but also shot down two and damaged a third! By 1942 they were replaced by more modern types, but Ansons continued to perform important work as trainers. Several versions were introduced during the war that instructed thousands of pilots, radio operators, and gunners throughout commonwealth air forces. Ansons remained in production until 1952; 11,020 had been constructed in Great Britain and Canada. The last six British aircraft served as communications aircraft until mustering out with great ceremony in

1968.

Type: Heavy Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 102 feet; length, 69 feet, 6 inches; height, 20 feet Weights: empty, 36,900 pounds; gross, 68,000 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 1,460-horsepower Rolls-Royce Merlin XX liquid-cooled in-line engines Performance: maximum speed, 287 miles per hour; ceiling, 24,500 feet; range, 660 miles Armament: 8 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 2,000 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1942-1954

|

T |

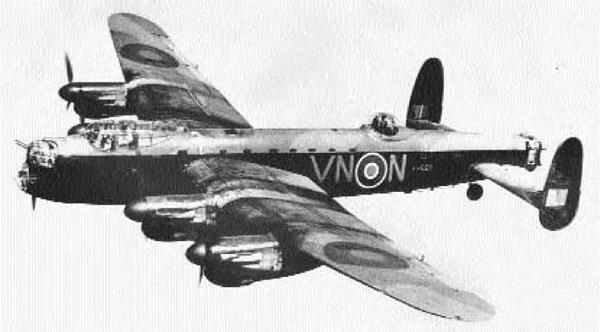

he Lancaster overcame troubled beginnings to become Britain’s legendary heavy bomber of World War II. Fitted with special ordnance, it gained special renown as the “Dam Buster.”

In 1936 the British Air Ministry released Specification P. 13/36 for a new twin-engine medium bomber. Avro originated the Manchester, which was a sound design but powered by totally unreliable Rolls-Royce Vulture engines. Two hundred of these unfortunate craft were built, but all left the service by 1942. However, the machine was refitted with an increased wingspan to accommodate four engines and rechristened the Lancaster. Thus was born the outstanding British night bomber of World War II. The Lancaster was an all-metal, high-wing monoplane with dual rudders. The fuselage was an oval-shaped, monocoque construction with a cavernous bomb bay extending half the length of the fuselage. This capacious feature could carry a variety of explosive and incendiary devices. The big bomber was rushed into production, with many Manchesters being converted while still on the production line. The new bomber commenced operations over Germany in March 1942, and within a

year Lancasters largely supplanted the Handley Page Halifaxes and Short Stirlings as the backbone of RAF Bomber Command. They proved instrumental in implementing the Royal Air Force policy of nighttime saturation bombing of German cities and industrial centers.

Lancasters distinguished themselves in the evening skies over Europe by delivering 608,612 tons of bombs in 156,000 sorties. However, they are best remembered for two very special attacks. The first, launched against the Mohne and Eder dams on May 17, 1943, utilized the famous Barnes Wallis “skipping bomb” that demolished its targets. The second fell upon the German battleship Tirpitz in Norway. On November 12, 1944, 31 Lancasters armed with 12,000-pound “Tallboy” bombs finally sank the dreaded raider in a fjord. By war’s end, Lancasters had been modified to carry the 22,000- pound “Grand Slam” bomb. Many subsequently joined the RAF Coastal Command and performed maritime reconnaissance work until 1954. A total of 7,377 were built, and a handful remained in Canadian service until 1964.

Type: Patrol-Bomber; Early Warning

Dimensions: wingspan, 120 feet; length, 87 feet, 4 inches; height, 16 feet, 9 inches Weights: empty, 57,000 pounds; gross, 98,000 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 9,820-horsepower Roll-Royce Griffon liquid cooled in-line engines Performance: maximum speed, 273 miles per hour; ceiling, 20,000 feet; range, 2,900 miles Armament: 2 x 20mm cannons; up to 20,00 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1951-1991

|

T |

he anachronistic Shackleton was the RAF’s first dedicated maritime patrol-bomber. Fitted with decidedly third-rate radar, it also served as England’s first distant-early-warning aircraft.

The Shackleton can trace its roots to the famous Avro Lancaster through an intermediary type, the Lincoln heavy bomber. In 1946 the Royal Air Force sought to replace its World War Il-vintage patrol-bombers with a completely modern type. A standard Lincoln was accordingly modified into a prototype maritime patrol craft, and the differences were so pronounced that a new designation became necessary. The new Shackleton utilized the same wing and undercarriage as its forebear but employed an all-new fuselage that was narrower and taller. The first MR 1 version did not become operational with the RAF Coastal Command until 1951. The following year the MR 2 appeared with an extended and heavily modified nose section. The final version, the MR 3, finally debuted in 1955. This craft featured a nosewheel, tricycle landing gear, and

fixed wingtip tanks to boost the already impressive cruise range. The dorsal turret was also deleted in favor of additional space, and a clear-view cockpit canopy was fitted. Moreover, to alleviate the strain of extended patrols on the crew, it also possessed such creature comforts as a soundproof wardroom. These durable craft performed well, and all were retired from maritime duties in 1971 by the jet-powered Hawker-Siddeley Nimrod.

Defense cuts in the late 1960s led to the mothballing of several aircraft carriers and, with them, the distant-early-warning Fairey Gannet aircraft. As a completely stopgap effort, 12 of the obsolete MR 2 Shackletons were then dusted off, fitted with the Gannet’s World War II-vintage radar, and employed as the new AEW 2. This was a ramshackle affair at best, but the British government saw fit to employ these flying museum pieces until their replacement by infinitely superior Boeing E-3A Sentries in 1991. Thus ended an aircraft dynasty that had served Britain long and well for nearly half a century.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 99 feet; length, 97 feet, 1 inch; height, 27 feet, 1 inch Weights: empty, unknown; gross, 200,000 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 20,000-pound thrust Bristol Olympus 301 turbojet engines Performance: maximum speed, 650 miles per hour; ceiling, 60,000 feet; range, 5,750 miles Armament: up to 21,000 pounds of conventional or nuclear weapons Service dates: 1957-1982

|

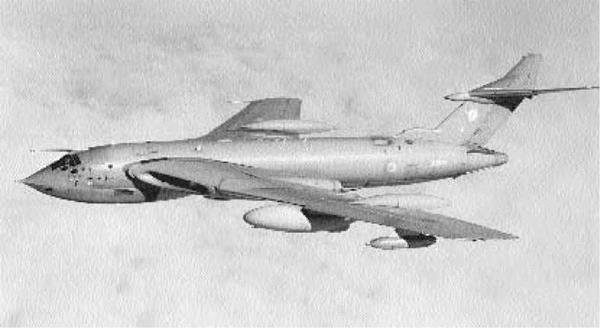

T |

he hulking Vulcan was the second of Britain’s famous “V” bombers and the first such craft outfitted with a delta wing. Although intended for a possible war with the Soviet Union, it fired its only shots in anger during the 1982 Falklands conflict.

A 1946 British air staff study recommended production of a trio of new strategic bombers that combined high speed, heavy payload, and great range. The Air Ministry then issued Specification B.35/46 to that effect, and an Avro design team under Roy Chadwick came up with a unique solution. They held that a large delta configuration was the best possible solution to all three requirements, especially in providing lift and, hence, range. A prototype of the huge craft was rolled out in August 1952 as the Vulcan. It was a very streamlined airplane, with the air intakes and engines buried within the wing and tricycle landing gear. The design was strong enough to be rolled in flight, and the prototype exhibited fighterlike qualities. The only major problem encountered was buffeting at high speeds,

which was corrected on production models by providing a kinked leading edge and a less swept-back wing. The Vulcan B.1 entered the service in 1957, and 45 were constructed. These were followed by 87 of the B.2 model in 1960, which had extensively modified flight-control surfaces and stronger engines. This version was also equipped to fire the nuclear-tipped Blue Steel standoff missile.

The Vulcans served capably in their roles as part of the West’s nuclear deterrent. However, when the Soviet Union finally perfected surface-to-air missile technology, the big bomber’s mission changed from high-altitude bombing to low-altitude penetration. New and better electronic countermeasures were installed, as well as an array of conventional bombs. The Vulcans were due to be phased out early in 1982 but earned a brief reprieve during the Falklands conflict with Argentina of that year, where a handful conducted very long-range bombing missions with mixed results. This memorable bomber’s replacement was the Panavia Tornado.