. Reggiane Re 2000/2001 Falco

Dimensions: wingspan, 36 feet, 1 inch; length, 27 feet, 5 inches; height, 10 feet, 2 inches

Weights: empty, 5,265 pounds; gross, 6,989 pounds

Power plant: 1 x Daimler-Benz DB 601A liquid-cooled in-line engine

Performance: maximum speed, 339 miles per hour; ceiling, 39,205 feet; range, 646 miles

Armament: 2 x 7.7mm machine guns; 2 x 12.7mm machine guns

Service dates: 1939-1945

|

T |

he Falcos were a capable series of Italian fighters, but available in only limited numbers. They enjoyed greater success as export machines, being operated by Sweden, Hungary, and Germany.

In 1938 the new Reggiane design office rolled out its first Re 2000 Falco (Falcon), which had been designed by Roberto Longhi. Superficially resembling the U. S. Seversky P 35 fighter of the same period, it was stubby and possessed large, elliptical wings. However, the Italian design offered clear improvements, being more streamlined and having retractable undercarriage that recessed into wing wells. Flight tests also revealed that the Re 2000 was an outstanding dogfighter and superior to the Bf 109 in a contest of slow turns. However, like all Italian fighters of the late 1930s, being driven by a low – power radial engine meant that it was relatively slow. This, and the fact that fuel was carried in unarmored tanks near the wing roots, caused the Regia Aeronautica (Italian air force) to reject the design. However, Sweden and Hungary expressed interest,

and the Re 2000 was acquired by both air forces in considerable numbers. The Regia Marina (Italian navy) also acquired 12 for possible catapult work aboard Italian battleships.

After Italy entered World War II in June 1940, Reggiane had greater access to advanced German engine technology. Longhi wasted no time refitting the Re 2000 with a powerful Daimler-Benz 601A inline engine—quite a feat considering the rotund fuselage—and created the Re 2001 Falco II. As predicted, this version possessed superior performance to the original design. It was deployed with some success over Malta in 1941, but a shortage of German engines limited its production to only 237 machines. Final development of the series culminated in the Re 2005 Sagittario (Archer) when the DB 605A engine was fitted to a totally redesigned, slender fuselage. This was quite possibly the greatest Italian fighter of the war, and the Germans coopted all 48 machines for their own use. These aircraft actively flew in the defense of Berlin until 1945.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 35 feet; length, 29 feet, 6 inches; height, 10 feet, 2 inches

Weights: empty, 1,274 pounds; gross, 1,600 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 70-horsepower Renault liquid-cooled in-line engine

Performance: maximum speed, 70 miles per hour; ceiling, 10,000 feet; range, 200 miles

Armament: up to 1 x.303-inch machine gun; 100 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1912-1918

|

T |

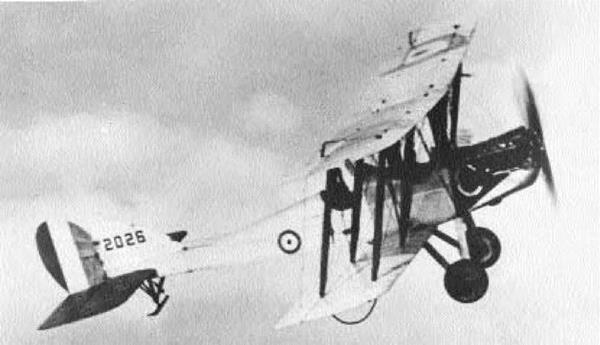

he slow, anachronistic BE 2s were among the first British aircraft dispatched to France in World War I. Despite staggering losses, bureaucratic inertia kept them in frontline service until the end of that conflict.

The BE 2a was designed and constructed in 1912 by Geoffrey de Havilland and was Britain’s first purely military aircraft. It was a two-bay biplane constructed entirely of wood and fabric, powered by an 80-horsepower engine. Despite its obvious frailty, the BE 2a possessed good performance for its day, was inherently stable, and was pleasant to fly. It therefore entered into production and, by the advent of World War I in August 1914, equipped three reconnaissance squadrons. BE 2s were the first British airplanes dispatched to France during the war, and in August 1914 they conducted the first British reconnaissance missions.

The pace of war quickly transformed the stately BE 2s into relics, a fact painfully underscored when

the machine gun-totting Fokker Eindekker debuted in 1915. The slow-flying BE 2s, unarmed and incapable of evasive maneuvers, were shot down in droves. The Royal Aircraft Factory was cognizant of these deficiencies and tried numerous modifications to improve performance, but to no avail. For many months in a service career that should have terminated speedily, the BE 2 remained the staple of “Fokker fodder.”

In light of the BE 2’s demonstrated obsolescence, it is difficult to account for why it was kept in frontline service for so long. The British government was certainly culpable on this point. In 1916 the most numerous version, the BE 2e, was introduced with a stronger engine and better armament, but the results were the same. The aging craft was finally transferred from the front in mid-1917 and relegated to training duties. It is regrettable that this docile aircraft was responsible for more Royal Air Corps casualties than any other type. A total of 3,535 of all models were built

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 47 feet, 9 inches; length, 32 feet, 3 inches; height, 12 feet, 7 inches Weights: empty, 1,993 pounds; gross, 2,970 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 120-horsepower Beardmore liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 80 miles per hour; ceiling, 9,000 feet; range, 250 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 350 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1916-1918

|

T |

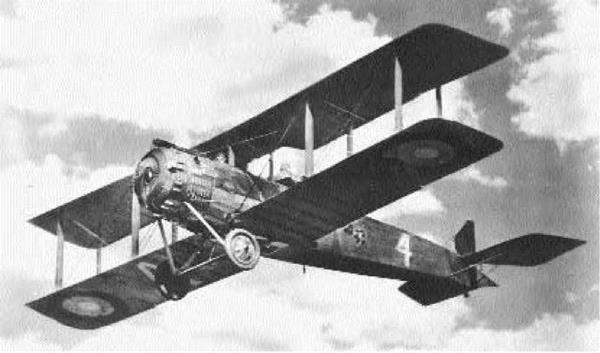

he venerable “Fee” was one of several capable pushers fielded by England during the World War I. It counted among many victims Max Immel – mann, the noted German ace.

The FE 2 (Fighter Experimental) evolved from a series of pusher aircraft constructed at Farnbor – ough in 1912. It was among the earliest warplanes designed in Great Britain, first flying there in 1913. The FE 2 consisted of a two-seat plywood and fabric-covered nacelle that also housed an engine. This unit sat suspended on struts between two wings of equal length, while four wooden booms extended rearward to a rudder and high-mounted tailplane. The forward nacelle seat contained a forward-firing machine gun and a second, telescopic-mounted weapon firing rearward over the top wing. To operate this weapon, the gunner stood up inside the cockpit while the aircraft was in flight. For all its relative crudeness, the FE 2 was a sound, good-handling machine, and a fine fighter for its day.

The first FE 2s did not reach the front until December 1915, but their impact was immediate. In concert with the de Havilland DH 2, the Fees outclassed the rampaging Fokker Eindekkers and helped eradicate them. On June 18, 1916, an FE 2 operated by No. 25 Squadron shot down and killed the famous ace Max Immelmann. Other German pilots like Karl Schaefer and Manfred von Richthofen were also injured while combating the deceptively doughty craft. The appearance of Al – batros and Halberstadt D II fighters that fall spelled the end of the FE 2’s career. However, being stable in flight and solidly built, they next took on responsibilities as night bombers. On April 5, 1917, the FE 2’s initial raid was against von Richthofen’s own aerodrome at Donai. The remaining craft were subsequently employed as trainers and in home defense units. FE 2s continued serving until the Armistice of 1918. An estimated 1,989 were constructed.

Type: Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 42 feet, 7 inches; length, 32 feet, 7 inches; height, 11 feet, 4 inches

Weights: empty, 1,803 pounds; gross, 2,869 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 150-horsepower RAF 4a liquid-cooled in-line engine

Performance: maximum speed, 103 miles per hour; ceiling, 13,500 feet; range, 400 miles

Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 250 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1917-1918

|

T |

he lumbering “Harry Tate” was built in greater numbers than any other British reconnaissance craft of World War I. Intended as a replacement for the unpopular BE 2, it was equally inadequate yet remained in production through the end of hostilities.

By the spring of 1916, the heavy loss of BE 2 aircraft forced the Royal Air Corps to request better machines capable of defending themselves. The Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough responded with the RE 8, which in many respects was simply a scaled-up BE 2. It too was a hulking, two-bay biplane with staggered wings of unequal length. Construction was plywood and fabric throughout, save for the metal cowling, and the upward-sloping rear fuselage gave it a decidedly “broken-back” appearance. It also had a small tail that during service life had to be enlarged to prevent spinning. But the RE 8 was well-armed by contemporary standards, possessing a synchronized Vickers machine gun for the pilot and a ring-mounted Lewis for the gunner. Like

the BE 2, the RE 8 was predictable and easy to fly, but it was inherently too stable for defensive maneuvers. Nonetheless, more than 4,077 were constructed over the next two years, with the first units reaching the Western Front in 1917.

Predictably, the RE 8s fended no better in combat than their earlier stablemates. The slow, stately craft simply lacked the agility to defend themselves against the fast, maneuverable German scouts, and they sustained heavy losses. With no suitable successor on the horizon, the RE 8s soldiered on, providing useful work in reconnaissance, artillery-spotting, and some occasional ground-attack work. Flight crews eventually admired its reliable qualities and nicknamed it “Harry Tate” after a noted vaudeville comedian. Despite their glaring shortcomings, RE 8s continued to provide valuable service through the end of the war. But it is unconscionable that the British Air Ministry allowed such a derelict to serve as long as it did—and at such great cost.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 26 feet, 7 inches; length, 20 feet, 11 inches; height, 9 feet, 6 inches Weights: empty, 1,531 pounds; gross, 2,048 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 200-horsepower Hispano-Suiza liquid-cooled radial engine Performance: maximum speed, 126 miles per hour; ceiling, 17,500 feet; range, 250 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 100 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1917-1918

|

T |

he SE 5a formed half of a famous British fighter duo from World War I. Although not as maneuverable as a Sopwith Camel, it was faster, more stable, and the preferred choice of several leading aces.

In 1916 the Royal Aircraft Factory began designing a new fighter around the 150-horsepower Hispano-Suiza engine. It was a standard two-bay biplane with rather angular features, for the wings, tail surfaces, and radiator were square. But the prototype SE 5 (Scout Experimental) successfully flew on November 16 with impressive results. It was fast, easily handled, and could dive with complete safety. Moreover, consistent with all Royal Aircraft Factory products, great emphasis had been placed on overall stability. Hence, it was an excellent gunnery platform, well-armed with a nose-mounted Vickers machine gun and a Lewis weapon firing over the top wing.

The SE 5 entered production in the spring of 1917, flew its first operational sorties that April, and

demonstrated mastery over the German Albatros D Vs, Pfalz D IIIs, and Fokker Dr Is opposing them. It could also hold its own against the superb Fokker D VII of 1918. The SE 5 was decidedly faster and could outclimb and outdive all its adversaries with ease. These features, combined with stable flying, made it the favored mount of leading aces like Edward Mannock, Albert Ball, and William Bishop. Possessing an in-line engine, it was not as maneuverable as the famous Sopwith Camel, but for the same reason it afforded novice pilots an easier time. By the summer of 1917 a stronger version, the SE 5a, appeared with the geared 200-horsepower French – manufactured Hispano-Suiza engine. This power plant was egregiously defective at first, and a series of similar British engines were installed in its place. By the 1918 Armistice 5,205 SE 5as had been delivered while another 50 were manufactured in the United States by Eberhardt. Most were retired immediately after the war.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 41 feet, 6 inches; length, 27 feet, 7 inches; height, 10 feet, 8 inches Weights: empty, 2,376 pounds; gross, 3,366 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 260-horsepower Mercedes D IVa liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 106 miles per hour; ceiling, 21,000 feet; range, 330 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns Service dates: 1917-1918

|

T |

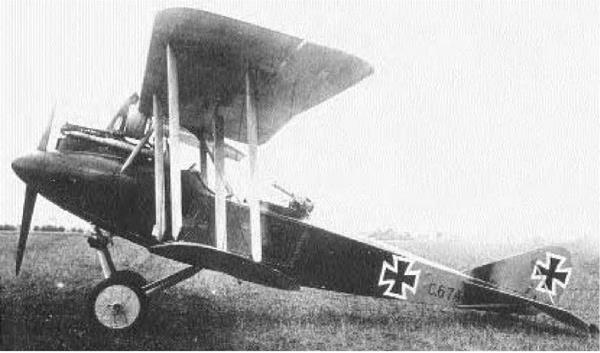

he excellent Rumplers were a common sight in the skies of Europe throughout World War I. They were among the highest-flying reconnaissance machines to serve during that conflict.

Since 1915 the Rumpler Flugzeugwerke had provided the German army with numerous two-seat aircraft, both armed and unarmed. The firm’s C I was a masterpiece of aeronautical engineering that debuted in 1915 and soldiered on at the front lines three years later. Toward the end of the war Dr. Edmund Rumpler decided to update his long-lived design with one better suited for long-range reconnaissance work. The new version, the C IV, was a departure from earlier conceptions. A two-bay biplane, it possessed slightly swept, highly efficient wings constructed of wood and fabric. The fuselage was also highly streamlined and mounted a pointed spinner on the propeller hub. The tail surfaces had also been revised and lost the triangular shape that was a Rumpler trademark. But more important, this craft was fitted with an excellent Mercedes D IVa engine, which gave it plenty of power at all altitudes.

The Rumpler C IV appeared at the front in February 1917 and was strikingly successful. It was one of the few aircraft that could routinely reach altitudes of 20,000 feet at speeds of 100 miles per hour. Consequently, Rumplers were considered among the most difficult German aircraft to shoot down. They were also ruggedly constructed and could absorb great damage. That fall work on an even better version was commenced, and the C VII emerged that winter. Externally, it was almost indistinguishable from the C IV but was powered by a high-compression Maybach Mb IV engine. This plane functioned as a high-altitude long-range reconnaissance platform. An even more highly specialized form, the Rubild (Rumpler photographic) also materialized. It was a stripped-down C VII fitted with heaters and oxygen equipment for the crew. Thus rendered, it easily reached unprecedented altitudes of 24,000 feet, where no Allied fighters could follow. The exemplary Rumpler machines continued serving with distinction until the war’s end.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 36 feet, 1 inch; length, 33 feet, 2 inches; height, 12 feet, 3 inches

Weights: empty, 10,141 pounds; gross, 17,637 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 5,000-pound thrust de Havilland Ghost turbojet engine

Performance: maximum speed, 659 miles per hour; ceiling, 45,000 feet; range, 1,677 miles

Armament: 4 x 20mm cannons; up to 24 x 76mm rockets

Service dates: 1951-1976

|

T |

he odd-looking J 29 set an important precedent by establishing Sweden at the forefront of military aviation. It was the first European jet with swept wings and enjoyed a lengthy service life.

Even before World War II had ended, the Swedish government resolved to enforce its longstanding policy of neutrality by acquiring modern warplanes. In 1945 Project 1001 was initiated by Saab to provide Sweden with its first jet fighter. The original design intended to mount straight wings and utilize the relatively weak de Havilland Goblin turbojet. However, awareness of German swept-wing technology, coupled with invention of the more powerful Ghost engine, caused fundamental revisions in the program. The design was modified, providing the wing with 25 degrees of sweep, and the fuselage was made more portly to accommodate the new engine. The resulting J 29 prototype first flew in September 1948 with excellent results. It was fast, ruggedly built in the tradition of Saab products, and highly maneuverable.

When wing-mounted air brakes were found to cause excessive flutter, they were subsequently relocated to the fuselage. The tricycle landing gear were also unique in that they inclined inward before retracting inside the fuselage. Three more years lapsed before the J 29 entered production and became operational as Europe’s first swept-wing jet fighter. Pilots took an immediate liking to the tubby craft, giving it the appropriate nickname Tunnan (Barrel).

A total of 661 J 29s were built until 1958 in six versions, all with successively better performance and endurance. The definitive model was the J 29F, constructed for ground-attack purposes and employing the effective Bofors rocket clusters. It also sported an afterburner and a sawtooth leading edge for better performance in the transonic range. The beloved Tunnans were slowly phased out after 1958, but several examples remained on active duty until 1973. In 1961 Austria obtained 30 J 29Fs and retained them in frontline service until 1993.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 30 feet, 10 inches; length, 50 feet, 4 inches; height, 12 feet, 9 inches

Weights: empty, 18,188 pounds; gross, 25,132 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 12,790-pound thrust Volvo RM6C turbojet engine

Performance: maximum speed, 1,321 miles per hour; ceiling, 49,200 feet; range, 350 miles

Armament: 1 x 30mm cannon; up to 6,393 pounds of air-to-air missiles

Service dates: 1960-1999

|

T |

he Draken, distinct with its double-delta configuration, was one of the world’s most advanced aircraft. It confirmed Sweden’s reputation for constructing high-performance aircraft with originality and flair.

In 1949 the Flygvapen (Swedish air force) issued stringent specifications for a new supersonic aircraft to replace the J 29 Tunnan. This evolved at a time when the only craft capable of such speeds was Bell’s famous experimental X-1. Nonetheless, the new machine had to be fast and display unprecedented rates of climb. It was also required to possess good STOL (short takeoff and landing) capabilities for operating off of highways and unprepared strips during dispersal. That year a Saab design teamed under Erik Bratt set about creating a minor aviation masterpiece when they opted to employ a unique double-delta. Such an arrangement promised great strength and internal volume with very little frontal area. The new machine could thus be crammed with fuel and avionics yet be difficult to ascertain head-on. It also promised excellent han

dling at fast as well as slow speeds. Several small – scale models and mock-ups followed before the first J 35 flew in October 1955. The aircraft was an outstanding success, although its engine failed to produce the Mach 2 speeds anticipated. It nonetheless entered production that year as the Draken (Dragon), reaching operational status in 1960. Production amounted to 660 machines.

Over time the Draken passed through successive variants that gradually improved its performance. Conceived as a bomber interceptor, the new J 35F mounted a pulse doppler radar, automatic fire – control systems, and advanced Hughes Falcon air – to-air missiles. This model could also fly at speeds in excess of Mach 2, exhibiting performance equal to the English Electric Lightning on only one engine. Drakens served Sweden well over four decades and were retired only in 1999. As they aged, they also became available for export, with Denmark and Finland obtaining several copies. However, the biggest user was Austria, which purchased 24 machines that are still in service.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber; Reconnaissance; Trainer

Dimensions: wingspan, 34 feet, 9 inches; length, 53 feet, 9 inches; height, 19 feet, 4 inches

Weights: empty, 33,069 pounds; gross, 45,194 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 28,100-pound thrust Volvo RM8B turbofan engine

Performance: maximum speed, 1,321 miles per hour; ceiling, 60,040 feet; range, 621 miles

Armament: 1 x 30mm cannon; up to 13,000 pounds of missiles, rockets, or bombs

Service dates: 1971-

|

T |

he racy Viggen (Thunderbolt) was history’s first canard fighter and a formidable interceptor. Until recently it formed the bulk of Swedish air strength, operating from hidden roadways deep in the woods.

In the 1960s Sweden began considering a replacement for its aging Saab J 32 Lansens. It was determined to develop a totally integrated approach to aerial defense called System 37, whereby a single airframe could be slightly modified to perform fighter, bomber, reconnaissance, and training functions economically. At length Saab took one of its usual departures from conventional wisdom by designing the J 37 Viggen in 1967. It was a sophisticated design for the time by incorporating small delta canards, equipped with flaps, just behind the cockpit. This complemented the larger, conventional delta wing perfectly, affording greater lift and maneuverability at lower speeds than plain deltas enjoyed. More important, canards allowed the Viggen to take off in relatively short distances. This was essential given the

wartime strategy of dispersing air assets into the woods and taxiing off roadways. To shorten landing distances even further, J 37s are equipped with built – in thrust reversers that automatically engage upon touchdown. This is an added safety feature for, given Sweden’s nominally icy conditions, applying airplane brakes in winter can be a chancy proposition at best. These machines became operational in 1971.

The first Viggens were optimized for ground attack, but subsequent variants successfully fulfilled interceptor, reconnaissance, and training missions. All look very similar at first glance, but the SK 37 trainer has a staggered second canopy behind the student cockpit. The final version, the JA 37, arrived in 1977 as a dedicated fighter intent on replacing the redoubtable J 35 Drakens. These are fitted with advanced multimode look down/shoot down radar and an uprated RM8B engine. The total production of all Viggens is 330; they will remain in service until replaced by superlative JAS 39 Gripens within a few years.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber; Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 26 feet, 3 inches; length, 46 feet, 3 inches; height, 15 feet, 5 inches

Weights: empty, 14,599 pounds; gross, 27,498 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 18,100-pound thrust Volvo RM12 turbofan engine

Performance: maximum speed, 1,321 miles per hour; ceiling, classified; range, 497 miles

Armament: 1 x 27mm cannon; up to 14,330 pounds of rockets, missiles, or bombs

Service dates: 1997-

|

T |

he futuristic Gripen (Griffon) is the third generation of advanced Saab fighters. Its lightweight, high-performance profile, coupled with digital avionics, make it one of the world’s most sophisticated warplanes.

By 1980 the JA 37 Viggen was showing its age, so the Swedish government initiated studies for a successor. At length stringent performance and fiscal conditions were established, which more or less ensured that the new machine would be lighter and smaller than the Viggen but even more capable. Furthermore, it was expected to simultaneously fulfill fighter, bomber, and reconnaissance missions currently performed by three versions of the former craft. This led to the new designation JAS (Jakt, Attack, and Sparing). Facing such requirements, Saab resurrected its previous canard-delta planform, although with some important changes. The new JAS 39 Gripen is a single-engine design with the wing moved from low – to midbody position. The small fixed canards were replaced with completely all-moving ones above the en

gine inlets. The new machine is constructed almost entirely of composite materials for lighter weight and greater strength. As before, the JAS 39 is designed with a fast sink rate for hard, abbreviated landings; in the absence of reverse thrusters, the canards point downward to act as air brakes. To ensure quick stops, the main wing is also fitted with a variety of flaps and elevons for additional drag. But the biggest changes are in the avionics. The JAS 39 is inherently unstable for greater maneuverability and utilizes fly-by-wire technology. Its onboard computers also allow the craft to perform any of three mission profiles by simply changing the software.

The first JAS 39 prototype flew in 1988 and demonstrated excellent, cost-effective qualities but was lost to a programming error. A second prototype also crashed in a stall, but most problems have since been rectified. The first Gripens became operational in 1997 and are slated to replace the Viggen within a decade. They are among the most advanced fighters ever built.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 38 feet, 8 inches; length, 27 feet, 10 inches; height, 9 feet, 6 inches Weights: empty, 1,354 pounds; gross, 2,954 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 260-horsepower Salmson Canton-Unne liquid-cooled radial engine Performance: maximum speed, 115 miles per hour; ceiling, 20,505 feet; range, 300 miles Armament: 3 x 7.7mm machine guns Service dates: 1918-1920

|

T |

his sturdy machine was one of the best French reconnaissance aircraft of World War I. It was a fine, if unexpected, achievement, considering how its designer was previously known for manufacturing engines.

In 1909 French industrialist Emile Salmson established the Societe des Moteurs Salmson firm for the express purpose of manufacturing water – cooled radial engines for aircraft. In the period prior to World War I, his products gained a reputation for reliability, which was further enhanced during the war years. In 1916 Salmson tried designing aircraft to go along with his engines. The first attempt, the Salmson SM 1, was an awkward-looking craft with propellers driven by chains—and a total failure. The following year he had better luck by completing the prototype Type 2, which utilized a more conventional approach. The new machine was a standard biplane with two-bay, unstaggered wings of equal length. The fuselage was circular in cross-section, made of fabric-covered wood, and mounted a heavily louvered metal cowling. A crew

of two sat in separate cockpits, although at such distance that communication was difficult. Nonetheless, French authorities were impressed, and the airplane went into production as the Salm – son 2A2 in the fall of 1917.

In service the Salmson was not particularly fast but proved robust and mechanically reliable. It was well adapted for photo reconnaissance and artillery-spotting, being sufficiently armed to defend itself. A total of 3,200 were constructed and outfitted 24 French squadrons during final phases of the war. Of this total, 705 2A2s were also purchased by the United States for the American Expeditionary Force. These machines were likewise extensively employed and won the admiration of their new owners. In one instance, a 2A2 flown by Lieutenant W. P. Irwin of the 1st Aero Squadron claimed eight attacking German fighters with his front gun! The Salmson was phased out shortly after the war, although it was subsequently exported to Japan. Others were refitted with enclosed rear cabins and flown as passenger ships by early European airlines.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 69 feet, 6 inches; length, 51 feet, 10 inches; height, 14 feet, 1 inch

Weights: empty, 14,991 pounds; gross, 23,104 pounds

Power plant: 3 x 780-horsepower Alfa-Romeo 126 RC34 radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 267 miles per hour; ceiling, 21,325 feet; range, 1,180 miles

Armament: 3 x 12.7mm machine guns; 2,755 pounds of bombs or torpedoes

Service dates: 1936-1952

|

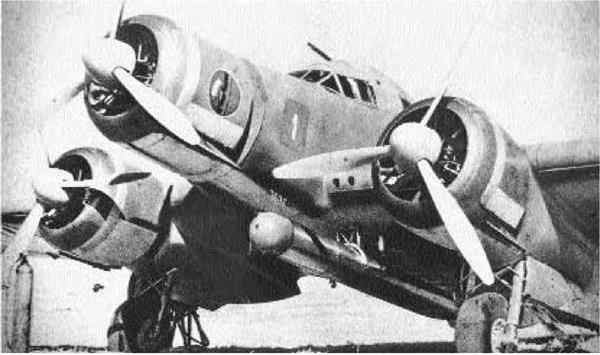

T |

he famous Sparviero (Sparrow) was the most capable Italian warplane of World War II. It gave excellent service as a bomber, torpedo plane, and reconnaissance craft.

The SM 79 was originally designed by Alessandro Marchetti as a high-speed, eight-passenger transport craft. It was a very streamlined, trimotor machine with retractable landing gear and constructed of steel tubing, wood, and fabric covering. It first flew in 1934 and established several international speed and distance records. Eventually the Regia Aeronautica (Italian air force) expressed interest in it as a potential bomber, and a prototype emerged in 1935. The military Sparviero was outwardly similar to the transport save for a bombardment gondola under the fuselage and a somewhat “humped” top profile to accommodate two gun turrets. Consequently, crew members nicknamed it Il Gobbo (The Hunchback) and several were deployed to fight in the Spanish Civil War. The SM 79 quickly established itself as a fast, rugged aircraft that handled extremely well under combat condi

tions. Its reputation induced Yugoslavia to import 45 machines in 1938. The following year a torpedo – bomber version, the SM 79-II, was deployed. Italy had helped pioneer the art of aerial torpedo bombardment, so when their efficient weapons were paired with the Sparviero, a formidable combination arose. By the time Italy entered World War II in 1940, SM 79s formed half of that nation’s bomber strength.

Early on, the SM 79 established itself as the most effective aircraft in the Italian arsenal. It performed well under trying conditions in North Africa and gave a good account of itself as a bomber. Sparvieros were also responsible for torpedoing several British warships in the Mediterranean. After the 1943 Italian surrender, surviving machines served both sides, with Germany developing a final version, the SM 79-III, which was deployed in small numbers. After the war, many Sparvieros reverted back to transports with the new Italian air force. These served capably until being replaced by more modern designs in 1952.