. Dassault/Dornier Alphajet

Type: Trainer; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 29 feet, 10 inches; length, 38 feet, 6 inches; height, 14 feet, 2 inches Weights: empty, 7,374 pounds; gross, 17,637 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 2,976-pound thrust SNECMA/Turbomeca Larzac turbojet engines Performance: maximum speed, 621 miles per hour; ceiling, 14,630 feet; range, 764 miles Armament: none, or up to 5,511 pounds of bombs, rockets, or gunpods Service dates: 1978-

|

T |

he Alphajet was a Franco-German effort to build a modern jet trainer easily adapted to ground-attack missions. The design functioned well and continues to serve with the air forces of several nations.

By 1968 the rising expense associated with modern military aircraft induced two former enemies, France and Germany, to undertake joint development of an advanced trainer/light strike aircraft for their respective air forces. The new craft was intended to replace a host of aging Fouga Magisters, Lockheed T- 33s, and Fiat G 91s. Two highly respected firms, Dassault and Dornier, then spent several years working out the final details before developing a prototype. The first Alphajet flew in 1975 as a modern shoulderwing jet seating two crew members under a lengthy canopy. The rear seat is also staggered above the front one to afford instructors better forward vision. The wings and tail surfaces are all highly swept, and the final product compact yet attractive. The craft also possesses twin engines—a Luftwaffe requirement resulting from its unsavory experience with single-en

gine Lockheed F-104 Starfighters. Given their dual function, the French and German versions differ widely as to avionics. The French use them as dedicated advanced trainers with less powerful systems. The Germans, meanwhile, fly theirs with the backseat removed and mount highly sophisticated radar, targeting, and communications equipment. Curiously, either version of the Alphajet can be rigged for ground attack with the addition of weapons pods and bombs. A total of 600 were built by 1982.

This high-performance package naturally aroused the interest of poorer nations, which sought increased firepower at bargain prices. Belgium, Egypt, Ivory Coast, Morocco, Nigeria, Qatar, Cameroon, and Togo all have purchased the diminutive craft and arrayed them with various weapons arrangements. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Germany decided to mothball its fleet of Alphajets and has since sold 80 refurbished machines to Portugal. France, meanwhile, continues to upgrade its trainers, calling the new machines Lanciers.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 28 feet, 3 inches; length, 25 feet, 2 inches; height, 9 feet, 6 inches

Weights: empty, 943 pounds; gross, 1,441 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 100-horsepower Gnome Monosoupape rotary engine

Performance: maximum speed, 93 miles per hour; ceiling, 14,000 feet; range, 250 miles

Armament: 1 x.303-inch machine gun

Service dates: 1916-1917

|

T |

he fragile-looking DH 2 was the Royal Flying Corps’s first true fighter plane. Tough and maneuverable, its appearance signified the end of Germany’s “Fokker scourge.”

The DH 2 single-seat fighter craft evolved from Geoffrey de Havilland’s earlier DH 1 two-seat reconnaissance craft in 1915. Like its predecessor, the pilot sat in a central nacelle well forward of the two – bay wings, enjoying unrestricted frontal vision. The rotary pusher engine was immediately to his rear. The wings were conventional wood and canvas affairs, and four tail booms jutted rearward and attached to a vee-shaped structure fastening the tail. De Havilland opted for a pusher design because the British still lacked synchronization technology that permitted firing machine guns through a propeller arc. Therefore, the DH 2 possessed a single drum – fed Lewis machine gun mounted in the pilot’s nacelle. In flight the craft flew only moderately fast, but it climbed well and was completely acrobatic.

The first DH 2s were deployed to France in January 1916 with No. 24 Squadron—the first purely

conceived fighter unit ever operated by the Royal Flying Corps. Prior to this, British formations were mixed bags of various kinds of aircraft. Air superiority at this time had passed completely into German hands because of the notorious, machine gun-armed Fokker Eindekker. But the DH 2s, despite their unconventional appearance, proved first – class dogfighters and swept the sky of German opposition. On one occasion, a single pusher flown by Major L. W.B. Rees mistakenly joined what he thought were 10 British bombers returning from a raid. They turned out to be German, and in the ensuing scrape his DH 2 dispatched two of the enemy and scattered the rest. Rees subsequently received the Victoria Cross.

In the fall of 1916 the first Albatros D Is and D Ils appeared, and de Havilland’s little pushers became completely outclassed. They sustained heavy losses before withdrawing from frontline service in

1917. Nonetheless, the DH 2 had made its mark as Britain’s first successful fighter.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 42 feet, 5 inches; length, 30 feet, 8 inches; height, 11 feet Weights: empty, 2,300 pounds; gross, 3,472 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 375-horsepower Rolls-Royce Eagle liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 136 miles per hour; ceiling, 20,000 feet; range, 420 miles Armament: up to 4 x.303-inch machine guns; 460 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1917-1932

|

T |

he DH 4 was the first British aircraft specifically designed for daylight bombing and among the best of its kind in World War I. It was built in even greater numbers by the United States and enjoyed considerable longevity there.

The DH 4 was designed in response to a 1916 Air Ministry specification for a new daylight-bombing aircraft, the first acquired by the Royal Flying Corps. A prototype was flown in August of that year and proved entirely successful. The DH 4 was a standard two-bay biplane constructed of wood and fabric. The fuselage consisted of two complete halves bolted together, with the forward half covered in plywood for greater strength. Another distinguishing feature was the widely spaced cockpits, between which sat a large fuel tank. Such placement facilitated better views for the pilot and gunner but rather hindered close cooperation. It was also fitted with dual flight controls for both crew members. The DH 4 was originally supposed to be powered by the splendid Rolls-Royce Eagle engine but they

proved unavailable, so several other power plants were employed.

In service the DH 4 was a superb airplane. Fully loaded, it was as fast as most fighters and could absorb considerable damage. Great numbers were employed by both the Royal Flying Corps and its naval equivalent, and it enjoyed a wide-ranging career from France to Palestine. As such, DH 4s were successfully employed in bombing, reconnaissance, and antisubmarine patrols. In August 1918 a Royal Navy DH 4 even managed to shoot down a Zeppelin L 70. The DH 4 was also the only British warplane to be manufactured in great numbers by the United States; the U. S.-built machines were powered by the famous Liberty in-line engine. By 1918 DH 4s equipped no less that 11 American and nine Royal Air Force squadrons. The British, who built 1,449 examples, discarded them after the war, but the Americans went on to construct an additional 4,686 machines. They underwent constant modifications and remained in service until 1932.

Type: Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 45 feet, 11 inches; length, 30 feet, 3 inches; height, 11 feet, 4 inches Weights: empty, 2,800 pounds; gross, 4,645 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 400-horsepower Packard Liberty liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 123 miles per hour; ceiling, 16,750 feet; range, 600 miles Armament: 3 x.303-inch machine guns; 660 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1918-1931

|

T |

he original DH 9, which suffered from a poor engine, had been foisted upon the Royal Flying Corps through governmental bureaucracy and proved a disaster. Fortunately, the much improved DH 9a became a splendid bomber it its own right and subsequently accrued a distinguished service record.

By 1917 the rising tempo of German raids against England forced the British High Command to increase its own bomber force for retaliatory purposes. The government then decided to replace the excellent DH 4 with an updated version, christened the DH 9. This new machine utilized the same wing and empennage as the DH 4, but it enjoyed closer cockpits and a new—and theoretically more powerful—BHP engine. However, in service the BHP was underpowered and completely unreliable, making the DH 9’s performance inferior to the craft it was meant to replace. Also, their low-ceiling performance subjected them to attacks by both fighters and antiaircraft batteries; in time losses grew prohibitive. Despite appeals from General Hugh Tren-

chard to get rid of the DH 9 altogether, the government had other priorities, and full-scale production was maintained. A total of 4,000 were acquired.

In view of the DH 9’s poor performance, a new version, the DH 9a, was developed. This appeared very similar to the old craft, although it employed greater wingspan and a stronger fuselage. Shortages of the splendid Rolls-Royce Eagle engine forced it to employ the 400-horsepower Liberty engine, built in the United States. The result of coupling a good engine to a fine airframe was an excellent aircraft that went by the sobriquet of “Nine-ack.” DH 9as fought with distinction toward the end of World War I and remained in production after the Armistice. No less than 2,500 were built during the postwar period, and they continued in frontline service until 1931. Nine – acks were best remembered for the policing role they fulfilled across the British Empire, particularly along the North-West Frontier of India. Their reliable performance was greatly appreciated by crews, because crash-landing usually meant death at the hands of hostile tribesmen.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 65 feet, 6 inches; length, 39 feet, 7 inches; height, 14 feet, 6 inches Weights: empty, 5,585 pounds; gross, 9,000 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 400-horsepower Packard Liberty liquid-cooled in-line engines Performance: maximum speed, 112 miles per hour; ceiling, 17,000 feet; range, 600 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns; 1,280 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1918-1922

|

T |

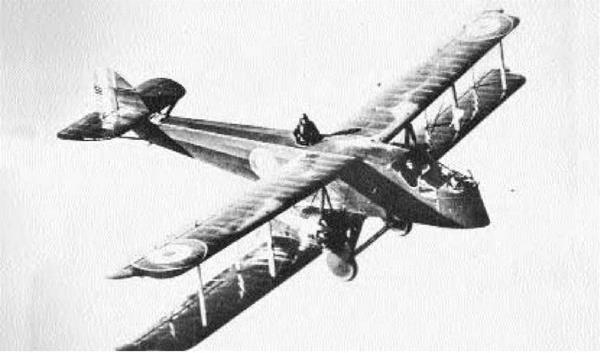

he jut-jawed DH 10 was one of the finest bomber designs of World War I, but it arrived too late for combat. It is best remembered as a postwar mail carrier that pioneered vital air routes in Europe, Egypt, and India.

In 1916 Geoffrey de Havilland designed a twin – engine pusher-type bomber known informally as the DH 3. It was a proficient design, and the Air Ministry placed an order for 50 machines. When production was canceled before the first example could be built, the project was summarily shelved until 1917. That year a new specification for heavy bombers was circulated, and de Havilland decided to upgrade his previous design. The resulting craft was named the DH 10, a three-seat, three-bay biplane pusher. It was distinct in that the fuselage was slung low, partially covered in plywood, and it employed a wide – track undercarriage. An ongoing shortage of Rolls – Royce engines prompted switching to the reliable American Liberty model, which were ultimately

mounted in tractor position. As a bomber the DH 10 hoisted twice the bomb load of the DH 9a at higher speed and altitude. In the summer of 1918 a contract for 1,275 machines was placed.

The DH 10 was an excellent bomber for its day, strongly built and easy to fly. Had the war continued it would have become very numerous, but only eight had arrived in France by the time of the Armistice. Production then ceased at 223 machines, which were dispersed among various squadrons in Europe, Africa, and India. The DH 10 spent the rest of its days as a utility craft, most notably as a mail carrier. In 1919 the machines of No. 120 Squadron commenced the first night service between Hawkinge, England, and Cologne, Germany. Similar work was performed by DH 10s of No. 216 Squadron along the Cairo-to-Baghdad route. It finally had an opportunity to drop bombs in 1920-1922, during a revolt of rebel tribesmen along India’s North-West Frontier.

Type: Trainer

Dimensions: wingspan, 29 feet, 4 inches; length, 23 feet, 11 inches; height, 8 feet, 9 inches

Weights: empty, 1,200 pounds; gross, 1,825 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 120-horsepower DH Gypsy liquid-cooled in-line engine

Performance: maximum speed, 109 miles per hour; ceiling, 13,600 feet; range, 300 miles

Armament: none

Service dates: 1932-1947

|

T |

he ubiquitous Tiger Moth was the last biplane trainer of the Royal Air Force and among the most numerous. During World War II it trained thousands of British and Commonwealth pilots from around the globe.

The great commercial and acrobatic success of de Havilland’s Moth aircraft in the late 1920s caused military circles to consider its adoption as a trainer. Around that time the RAF began employing the popular DH 60T Gypsy Moth variant, which had been modified to allow pilots easier escape from the front cockpit while wearing a parachute. This meant staggering the top wing forward and providing it with several degrees of sweep. After several more refinements, it was introduced into the service as the DH 82 Tiger Moth, quite possibly the greatest biplane trainer of all time. This fabric-covered, compact little craft had single-bay wings and an inverted engine to improve the frontal view. As airplanes, Tiger Moths were gentle and forgiving—perfect for training inexperienced pilots. However, they were also strong,

completely acrobatic, and could be literally thrown around the sky with abandon. A second model, the DH 82A Tiger Moth II, mounted a canvas hood over the rear cockpit to teach instrument flying.

By the advent of World War II in 1939, 1,611 Tiger Moths were in use at 28 Elementary Flying Schools across Britain. During the war the number of machines increased exponentially, with more than 8,000 being manufactured in England, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Literally thousands of Commonwealth pilots took the first step toward winning their wings by strapping themselves into Tiger Moths! During the war, several DH 82s were impressed into service as communications aircraft and flying ambulances. The threatened invasion of England in 1940 prompted others to be fitted with bomb racks. A radio-controlled version, the Queen Bee, also served as a flying drone for aerial gunnery. After the war, Tiger Moths remained frontline trainers until 1947. Hundreds still fly today in private hands, and they remain beloved machines.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 54 feet, 2 inches; length, 41 feet, 6 inches; height, 15 feet, 3 inches Weights: empty, 16,631 pounds; gross, 25,500 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 1,710-horsepower Rolls-Royce Merlin 76 liquid-cooled in-line engines Performance: maximum speed, 425 miles per hour; ceiling, 36,000 feet; range, 3,500 miles Armament: 4 x 20mm cannons; 4 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 4,000 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1941-1955

|

H |

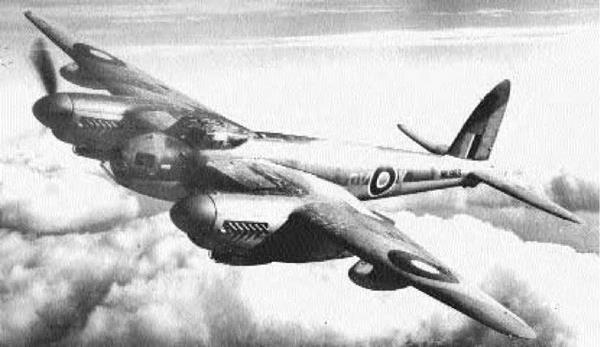

ailed as the “Wooden Wonder,” the Mosquito was among the most versatile and proficient warplanes of World War II. It saw service in a countless variety of roles and enjoyed the lowest loss rate of any Royal Air Force aircraft.

In 1938 the de Havilland company proposed a high-speed reconnaissance aircraft flown by only two men. The new craft would be totally unarmed, relying solely upon speed for survival. Moreover, to de-emphasize use of strategic resources like metal, de Havilland wanted the plane entirely made from wood. Understandably, officials at the Air Ministry simply scoffed at the proposal. The company nonetheless proceeded to construct several prototypes that first flew in 1940. The country was at war with Germany then, and severely hard-pressed, but ministry officials remained hostile to the notion of wooden warplanes. Their minds completely changed when the first Mosquitos demonstrated speeds and maneuverability usually associated with single-engine fighters. The aircraft was then rushed into production and flew its first daylight reconnais

sance mission over Paris in 1941. When the “Mossies” easily outpaced pursuing German fighters, a legend was born.

During the next four years, de Havilland produced great quantities of Mosquitos in a bewildering variety of types. They capably performed several roles with distinction: reconnaissance, night fighter, day fighter, and light bomber. Fast and almost unstoppable, Mosquitos were also famous for their pinpoint accurate bombing raids. In January 1943 they interrupted a speech given by Luftwaffe chief Hermann Goring—then returned later that day to drop bombs on a rally given by propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels. Lightning raids against Gestapo headquarters in The Hague and Copenhagen were also a specialty. Mosquitos served in Europe, the Mediterranean, and the Pacific, suffering the lowest loss rate of any British aircraft. After the war they remained the fastest machines in RAF Bomber Command inventory until overtaken by Canberra jet bombers in 1951. A total of 7,781 Mosquitos were built—truly one of the world’s greatest warplanes.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber; Trainer

Dimensions: wingspan, 38 feet; length, 30 feet, 9 inches; height, 8 feet, 10 inches

Weights: empty, 7,283 pounds; gross, 12,390 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 3,350-pound thrust de Havilland Goblin turbojet engine

Performance: maximum speed, 548 miles per hour; ceiling, 42,800 feet; range, 1,220 miles

Armament: 4 x 20mm cannons; 2,000 pounds of bombs or rockets

Service dates: 1946-1990

|

T |

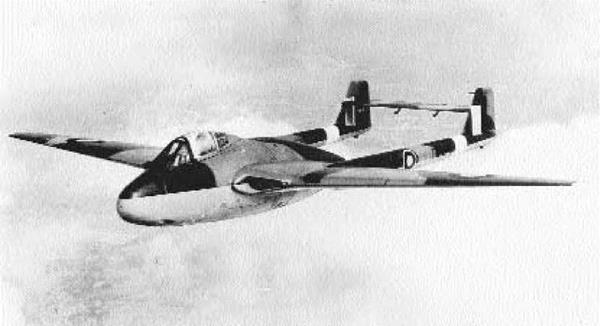

he diminutive Vampire was England’s second jet fighter and spawned a large number of subtypes. It enjoyed a lengthy career and was exported to no less than 25 nations.

The British Air Ministry issued Specification

E. 6/41 in 1941 to obtain a jet fighter built around a single de Havilland Goblin centrifugal-flow turbojet. The relatively low thrust of this early engine virtually dictated the design because of the necessity to keep the tailpipe as short as possible. De Havilland responded with a unique twin-boomed approach. The fuselage was a bulbous pod housing the pilot, engine, nosewheel, and armament. The pilot sat in a cockpit close to the nose and under a bubble canopy that afforded excellent vision. The all-metal wing was midmounted and affixed by twin booms extending rearward, themselves joined by a single stabilizer. The prototype first flew in September 1943, with Geoffrey de Havilland Jr. at the controls. He reported excellent flight characteristics, even at breathtaking

speeds of 500 miles per hour. In 1946 the aircraft entered the service as the DH 100 Vampire (the original designation was Spider Crab). Subsequent modifications yielded the Mk III, which had larger fuel tanks and a redesigned tail. However, it was not until 1949 that the major production version, the FB Mk 5, arrived. It featured clipped wings, longer undercarriage, and the ability to carry rockets and bombs.

The Vampire exhibited such docile handling in flight that it was an ideal trainer. It was also exported around the world and saw extensive service with 25 air forces. Switzerland operated its Vampires with little interruption until 1991. On December 3, 1945, a Royal Navy Sea Vampire also became the first pure jet to operate off a carrier deck. This version, naturally, was stressed for catapulting and used an arrester hook. One final model, the NF Mk 10, was a two-seat night fighter version with radar. The total number of Vampires manufactured was around 2,000. It was a classic early jet design.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 50 feet; length, 55 feet, 7 inches; height, 10 feet, 9 inches Weights: empty, 22,000; gross, 36,000 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 11,250-pound thrust Rolls-Royce Avon turbojet engines Performance: maximum speed, 650 miles per hour; ceiling, 48,000 feet; range, 600 miles Armament: 4 x Firestreak, Red Top, or Bullpup missiles Service dates: 1959-1972

|

T |

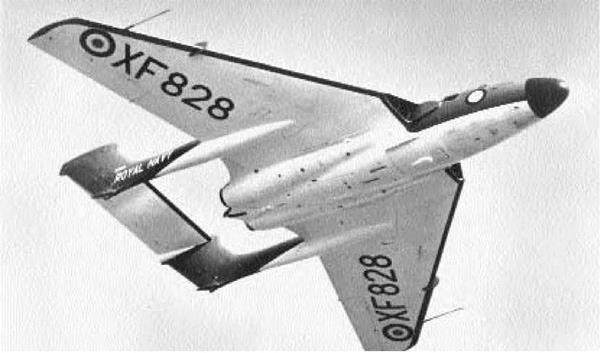

he formidable Sea Vixen compiled a litany of firsts for the Fleet Air Arm. It was the Royal Navy’s first all-weather interceptor, the first designed as an integrated weapons system, and the first armed solely with missiles.

In 1946 the British Admiralty issued Specification N.40/46, later upgraded to N.14/49, which instigated development of a twin-engine radar-equipped jet fighter. De Havilland, which had pioneered twin – boomed jet fighters, advanced the DH 110 design, but initially the navy rejected it in favor of the lower – powered Sea Venom. When the Royal Air Force also passed on it for what ultimately become the Gloster Javelin, the Fleet Air Arm took a second look and decided the craft was worth pursuing after all. The prototype debuted in 1951 as a most impressive warplane. The DH 110 was a large machine with the crew compartment and twin engines mounted within a central, streamlined pod. The twin booms streamed back from the highly swept wing and were

joined farther aft by a single control surface. The pilot and radar operator sat side by side, but only the pilot was provided with a canopy, offset to the left. The DH 110 was a powerful flier, and during early testing it became the first British aircraft to break the sound barrier in a dive. When the prototype subsequently broke up in flight, development halted and several years of bureaucratic indecision ensued. Consequently, the first FAW.1 Sea Vixens did not reach the fleet until 1959.

In service the Sea Vixen proved itself a powerful addition to the fleet, both as an interceptor and a ground-attack plane (mounting U. S.-made Bullpup guided missiles). By 1961 a new version, the FAW.2, appeared, featuring revised booms extending over the front wing to carry additional fuel. This model also was the first navy fighter to dispense with cannons entirely in favor of four Firestreak or Red Top missiles. A total of 148 Sea Vixens were built, with the last retiring in 1972.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber; Night Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 41 feet, 8 inches; length, 33 feet; height, 6 feet, 8 inches

Weights: empty, 8,100 pounds; gross, 15,310 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 4,850-pound thrust de Havilland Ghost turbojet engine

Performance: maximum speed, 640 miles per hour; ceiling, 45,000 feet; range, 1,075 miles

Armament: 4 x 20mm cannons; up to 2,000 pounds of bombs and rockets

Service dates: 1952-1990

|

T |

he Venom was a successor to the earlier Vam – л. pire, but not nearly as popular. It nonetheless filled a critical niche in several areas until more advanced machines could be deployed.

Continuing refinement of the de Havilland Goblin engine resulted in a totally new version, the Ghost, which featured 50 percent more thrust. This power plant was fitted into a heavily redesigned DH 100 Vampire in 1949, and the resulting hybrid gained a new designation as the DH 112 Venom. It bore striking similarity to its forebear, but it enjoyed the advantage of a wholly redesigned, thinner wing of broader chord. Consequently, the Venom possessed much higher performance than the Vampire. The Royal Air Force immediately ordered the type into production, and it became operational in 1952. The Venom was employed initially as a fighter-bomber, and the FB.1s and FB.4s could carry useful payloads. Both France and Switzerland obtained license to manufacture the craft domestically; the Swiss

models flew regularly in frontline service up to 1990. Two night-fighter versions, the NF.2 and NF.3 were also developed that sat a crew of two side by side. These superceded the Vampire NF 10s after 1953 and rendered useful service until being replaced by Gloster Javelins in 1957.

The Fleet Air Arm was naturally interested in such good performance, and in 1954 it accepted deliveries of the Sea Venom FAW. These were the Royal Navy’s first all-weather interceptor and featured arrester hooks, folding wings, and other naval equipment. They also sat a crew of two in side-byside configuration. In 1956 Sea Venoms were at the forefront of the Anglo-French intervention during the Suez Crisis, making large-scale ground attacks in support of army units. Two years later Sea Venoms pioneered the use of Firestreak guided missiles as standard Fleet Air Arm armament. They served well until the arrival of the de Havilland DH 110 Sea Vixen in 1959. Around 500 of all types were built.