Difficulties in the South

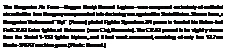

days of the war was met in the southern combat zone, where the first mission of Luftflotte 4 was to attack and destroy the Soviet Air Force in this area. Fliegerkorps V—with the Bf 109s of JG 3 as the main fighter unit – operated on the northern (left) flank. Fliegerkorps IV— to which the Bf 109s of JG 77 and I.(J)/LG 2 w’ere assigned—was given the task of achieving air superiority on the Soviet-Romanian front.

Stalin had concentrated the strongest defense forces and the best equipment in this area. At the same time, this was the sector given the lowest priority by Hitler. Here the Soviet early warning system worked much better than farther to the north. The NKVD border troops were alerted and offered frantic resistance. The entire area was covered with dense forests and crisscrossed with numerous rivers and creeks. On top of this, most roads here were in even worse shape than those to the north.

![]()

While the VVS on the central combat zone was more or less paralyzed on June 23 by the crippling blows dealt by the Luftwaffe on the first day of the war, the Soviet Air Force in the southern combat zone managed to maintain a high level of activity, mainly due to the quality of the air force commanders in this area. On the first day of the war, General-Mayor Yevgeniy Ptukhin, commander of VVS-КОVO/Southwestern Front, had instructed his bomber and ground-attack units to concentrate all efforts against the advancing enemy columns and the airfields of the enemy. The fighter regiments received orders to protect the Soviet troops at the front from Luftwaffe attacks.

While the VVS on the central combat zone was more or less paralyzed on June 23 by the crippling blows dealt by the Luftwaffe on the first day of the war, the Soviet Air Force in the southern combat zone managed to maintain a high level of activity, mainly due to the quality of the air force commanders in this area. On the first day of the war, General-Mayor Yevgeniy Ptukhin, commander of VVS-КОVO/Southwestern Front, had instructed his bomber and ground-attack units to concentrate all efforts against the advancing enemy columns and the airfields of the enemy. The fighter regiments received orders to protect the Soviet troops at the front from Luftwaffe attacks.

The advancing German troops found that all bridges across the rivers in the border area had been blown up by the retreating Soviets, and as soon as the Germans constructed new bridges, Soviet aircraft arrived in scores to destroy them.

“Ivan came buzzing in huge masses” according to Hauptmann Hans von Hahn, who flew with T./JG 3 over the spearheads of Panzergruppe 1 during the first days of the war. I./JG 3 was credited with the destruction of nineteen enemy aircraft, all SB – and DB-3 bombers, in the air on June 23 alone.

Nowhere did the Luftwaffe encounter as strong opposition in the air as did Fliegerkorps IV on the Soviet-Romanian border. Of 827 first-line aircraft in WS-

Odessa Military District/Southcrn Front, more than one hundred were MiG-3 fighters. In this area some of the most skillful VVS fighter pilots were active. Noteworthy were Starshiy Leytenants Aleksandr Pokryshkin and Anatoliy Morozov and Kapitans Petr Kozachenko and Afanasiy Karmanov.

Having shot down a Soviet Su-2 bomber on the first day of the war, Starshiy Leytenant Pokryshkin, of 55 TAP, claimed his first “real” aerial victory against a Bf 109 on June 23.

That day, twenty Bf 109s of Stab and II./JG 77 attacked the Soviet airfields in the Kishinev area in Soviet-occupied Moldavia. They claimed eight aircraft destroyed on the ground and were involved in a difficult fight with the MiG-3s of 4 IAP. Карі tan Afanasiy Karmanov, a squadron leader in 4 IAP, claimed to have shot down three Bf 109s in this combat. Karmanov, who was one of the most experienced Soviet test pilots, had achieved his first two victories (a Ju 88 and a Bf 109) on the previous day. At most, one of his claims can he verified with German loss records—the Bf 109 piloted by Fcldvvcbcl Hans lllncr of 4./JG 77.

Having landed at Revaka Airfield in the vicinity for refueling his aircraft, Karmanov saw four Bf 109s approaching the airfield. Immediately, almost without fuel and ammunition, he trxrk off and attacked them. He was shot down and hailed out, but his parachute did not open and he fell to a certain death. Possibly this brave pilot fell victim to Ill./JG 77!s Oberleutnant Kurt Lasse, who claimed his fourth victory.

Over the same area, 249 lAP’s Kapitan Petr Kozachenko, one of the most: experienced Soviet fighter pilots, with fifteen victories over Japanese and Finnish aircraft, also scored his first victory in the Russo-German war on June 23. Intercepting twelve Нс 112B fighters of the Romanian FARR ’s Grupul 5 Vanatoare that attempted to raid Bolgrad southern Moldavia, Kozachenko, who was leading a formation of seven 1-І 53s, shot down the He 112 piloted by Adjutant Aviator Anghel Codnit before leading his group home without losses.2 ’

Meanwhile, the Soviet DBA and the

air force of the Soviet Black Sea Fleet (ChF) subjected Germany’s ally Romania to the heaviest Soviet strategic bombing raids made during the entire war.

air force of the Soviet Black Sea Fleet (ChF) subjected Germany’s ally Romania to the heaviest Soviet strategic bombing raids made during the entire war.

These raids were nevertheless flown under very primitive conditions, with inadequate planes, poor navigation equipment, and ill-aimed bombing. The port of Constanta was the main target.

Locotenent Aviator Horia Agarici of FARR’s Escadrila 53, equipped with Hurricane fighters, managed to down three DB-3s out of a force of seventy-three SBs and DB-3s that raided Constanta on June 23. The next day the Soviets fared better during the first raid of the day, in which eighteen SBs and eighteen DB-3s were able to drop 178 bombs over the airfield and oil fields at Constanta without loss.

Attempting to follow up this success later that day, a formation of thirty-two SBs and DB-3s lost ten bombers, nine of them to the Bf 109s of III./JG 52.

On June 24,55 IAP’s Starshiy Leytenant Pokryshkin was in “hot air” again, scoring his second “German” victory, yet another Bf 109, possibly piloted by 1I./JG 77’s Feldwebel Otto Kohler, who was killed in the air above the Soviet-Romanian border area in the vicinity of Iasi.

Starshiy Leytenant Konstantin Oborin of 146 IAP achieved the first nocturnal taran of the war during the night of June 24-25. While in the vicinity of Odessa, Starshiy Leytenant Oborin slammed his MiG-3 into a He 111 of 4./KG 27. The Heinkel went down over Soviet – held territory, but a second aircraft of the same Staffel landed close to the crash site, picked up the surviving and unhurt crewmen, and left for home before any Soviet soldiers appeared. The seriously injured MiG pilot managed to land his crippled fighter, but he died from his injuries on August 18, 1941.24

Even if they were encountering the best the VVS could field, the units of Luftflotte 4 proved to be vastly superior in the air. On June 25, a Schwarm of four Bf 109s led by Oberleutnant Walter Hoeckner of I1./JG 77 ran into a formation of twelve SB bombers escorted by the MiG-3s of 55 IAP. When the combat was over, ten SBs had been destroyed, of which Oberleutnant Hoeckner had lagged eight. Devastating blows were dealt to the Soviet Air Force on the ground even in this area.

Between June 22 and June 25, Fliegerkorps V on the left flank alone was credited with destroying 774 Soviet aircraft on the ground and 136 in the air.

After June 25, the main task of Fliegerkorps V was shifted from air-base raids to tactical support of the German Sixth Army and Panzergruppe 1 in the drive on Kiev. This was particularly important because Generaloberst Ewald von Kleist’s Panzergruppe 1 had run into large numbers of Soviet T-34 and KV tanks that effectively blocked any further German progress in the Novograd Volynskiy region, halfway to Kiev. The tank battle would last almost a week. Here the Soviets managed to achieve local superiority on the ground. The Germans were able to hold out only due to Fliegerkorps V. Covering the sky above the troops of Panzergruppe 1, JG 3 and I.(J)/LG 2 claimed to have shot down more than a hundred Soviet aircraft, the majority of them DB – 3 and SB bombers, during two days of large-scale air battles on June 25 and June 26. With one of the six Bf 109s downed in these battles, Hauptmann Lothar Keller, the twenty-victory ace commanding I1./JG 3, was lost.

On the Soviet-Romanian border, the MiG-3 pilots of Mayor Viktor Ivanov’s 55 LAP experienced a disheartening struggle—as was the case with all Soviet front-line aviation units during this period. On June 26, Starshiy Leytenant Pokryshkin claimed two Hs 126 reconnaissance aircraft (or, according to another source, one Hs 126 and one PZL P.24) in the Beltsy region, but he lost

his wingman, Mladshiy Leytenant Petr Dovbnya. On the following day, six MiG-3s, led by Mayor Ivanov, attacked a lone Hs 126. The regimental commander shot up the Henschel, but while attempting to finish off the flaming airplane, Ivanov’s wingman crashed and was killed.

The five remaining MiGs strafed an enemy truck column in the same area and suddenly were jumped by eight Bf 109s of II./JG 77. Pokryshkin turned to meet the enemy, but he found that none of his comrades had followed him; Mayor Ivanov and the rest simply escaped! The German fighter pilots split into two groups, four planes pursuing Ivanov’s fleeing formation and four entering combat with the lone MiG-3. Having failed in his first attack, Pokryshkin made a quick half loop and sought refuge in a thick cloud. Coming out of the cloud, he was lucky to find one Bf 109 diving just

in front of him. The Soviet ace pulled out of his dive and fired at the “Messer" from short distance. In the next second, tracers came whistling close to his own aircraft. Only by using all his skills, Pokryshkin managed to evade the attacking Messerschmitts during the following minutes. Realizing that this “Ivan" was too much for them—or simply because they were running out of fuel—the Bf 109s finally disengaged.

Returning to the airfield, Pokryshkin learned that one MiG-3 of Ivanov’s group had been shot up and force-landed. In 5./JG 77, Feldwehel Rudolf Schmidt claimed one MiG-3 as his fifteenth victory.

Shortly afterward, as a formation of enemy bombers approached Kishinev, Pokryshkin, Mladshiy Leytenant Leonid Diyachenko, and Mladshiy Leytenant Nikolay Lukashevich scrambled in the three MiG-3s that remained serviceable. They spotted seven Ju 88s, of which Pokryshkin and Diyachenko each shot down one. Then they were in turn bounced by four Bf 109s. Sasha Pokryshkin managed to escape, but Diyachenko was shot down, probably by Unteroffizier Hans Esser of 5./JG 77. Lukashevich re-

turned to base with the claim of one Bf 109. 5./JG 77’s Unteroffizier Loy made a successful forced landing near Iasi.

During the first week of the war, Aleksandr Pokryshkin claimed to have shot down six enemy aircraft-three Bf 109s, one Ju 88, and two Hs 126s. Unfortunately, all the 55 IAP documents were lost during the retreat, and most of these claims were never officially registered.

Having flown a number of raids against Constanta during the first days of the war, the Soviet bombers expanded their target list to include Bucharest and Iasi. Lacking fighter cover and performed mainly by the vulnerable SB bombers, these raids were tantamount to suicide.

On June 26, a large bomber formation attempted to cover a warship raid against the Romanian coast. During the approach flight the Soviet bombers were intercepted by Bf 109s from 8./JG 52 and III./JG 77. Each of the eight pilots of 1U./JG 77 participating in this combat returned to base with claims, including Leutnant Emil Omert and Oberfeldwebel Reinhold Schmetzer, who each

claimed five. The Staffelkapitan of 8./JG 52, Oberleutnant Gdnther Rail, comments: “It was a very – easy game, since the Russian bombers appeared without any fighter cover.”2:> In total, the Soviets registered nine bombers lost, all SBs from 40 BAP/ChF. In addition, the flotilla leader Moskva was sunk by a mine, and coast artillery damaged the flotilla leader Kharkov.

In the context of strategic air raids, the Romanian FARR carried out one of the most decisive strategic bombing missions in history during these days. On June 26, 1941, three P.37 Los bombers of the Romanian Grupul 4 Bombardament were sent on an ultrasecret mission: Posing as “Soviet” planes, they dropped thirty 50-pound bombs on the Hungarian town of Kosice with the intention of provoking Hungary to declare war on the USSR. Thirty-two people were killed and 280 injured.26 The sinister planning is revealed by the fact that one unexploded bomb (intentionally unarmed?) carried wTit – ings in Russian. The plot worked, and Hungary joined the war on the German side. On only the next day, the first sorties were flown by the Hungarian Air Force (Magyar Kiralyi Honved Legiero) against the Soviet

city of Stanislav, north of the Hungarian border.

city of Stanislav, north of the Hungarian border.

Magyar Кігйіуі Honved Legiero consisted of 530 combat aircraft, mainly relatively obsolescent models. One Fiat CR.42 from Fighter Squadron 2/3 was shot down during Hungary’s first day at war.

The pilot, Sergeant Laszlo Bardossy, was captured by the Soviets.

This action provoked a limited Soviet air raid against the Hungarian railway station at Csap two days later. The CR.42 fighters of Captain Zoltan Kiss’s Fighter Squadron 2/3 rose to intercept and claimed three SBs out of an attacking force of seven.

Meanwhile, the medium-bomber units of Fliegerkorps V—KG 51, KG 54, and KG 55—were involved in continous low-level attacks against the strong Soviet tank forces that blocked the way of Panzergruppe 1 on the road to Kiev. Other missions were flown against Soviet reinforcements in the rear. This resulted in the decisive delay of the Soviet XV Mechanized Corps. On June 26 the corps headquarters

was hit by an air attack in which the commander, General-Mayor Ignat Karpezo, was badly wounded.

|

Between June 22 and June 30 the Luftwaffe claimed to have destroyed 201 tanks in the southern combat zone, mainly in front of Panzergruppe 1. This onslaught finally permitted the German ground forces to break

through. On June 30 the Stavka decided to pull back the Southwestern Front.

The first nine days of the war in the southern combat zone had revealed that even the best forces the Sovi

ets could field were not comparable to the qualitative force of the Wehrmacht. The most decisive part was played by the Luftwaffe, which had put large parts of the WS out of action on the ground, shot down scores

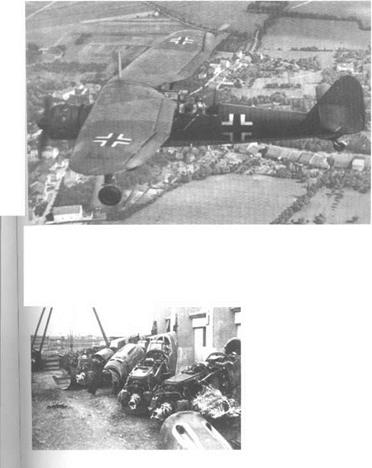

The high losses sustained by the Luftwaffe during the first phase of the war on the Eastern Front had not been anticipated by the German commanders. Seen in this photo are four damaged Bf 109s waiting to be transported to be refurbished by the aircraft industry in Germany. (Photo: Grislawski.)

of the modern MiG fighters, and made any serious Soviet attempt to hold a defense line impossible. Among such grievous losses, WS-Southem Front registered fifty- eight of its new MiG-3 fighters lost between June 22 and July l.2′ At the same time, the inabilities of the Soviet “strategic” bombers stood clear. The first air raids against Romania had been disasters, although only weak fighter forces opposed the attackers. Only due to a later radical change in tactics were the Soviets able to continue these raids on a scale larger than a nuisance level.

After only two weeks, victory seemed to be in sight for Hitler. But to those who knew the Soviet Union, things looked different. Hitler’s Luftwaffe had played a major part in inflicting unprecedented losses on the Red Army. But air strategists were already raising their voices in warning. Not only had the number of serviceable German aircraft at the front fallen dramatically—by June 30, the operational strength of the Luftwaffe on the Eastern Front had dropped to 960 aircraft—it could also be clearly seen that the Luftwaffe was becoming little more than a complement to the army.

In general, the main doctrine of the Luftwaffe was tactical and operational—to act in immediate support of the Blitzkrieg ground forces. This had been one of the most important keys to the rapid victories over Poland in 1939, France in 1940, and the Balkans in the spring of 1941. This Blitzkrieg doctrine also was a dominant reason for the German success during the initial stages of Operation Barbarossa. But as the German Army continued its march into the Soviet Union, increasing losses in combination with the vast operational area soon created a situation in which the strung-out German divisions became totally dependent on close support from the air. At the same time, the daily rate in attrition caused a rapid decrease of the number of aircraft available to the Luftwaffe combat units. After only a few days, the medium bombers—originally intended to strike at supply columns, airfields, bridges, and other targets in the enemy’s rear—had to be used in close-support missions in the immediate front-line zone. With this, the Luftwaffe was gradually reduced more or less to what can be described as a “flying artillery” force. This in turn badly affected the ability of the Germans to isolate the Soviet front lines from the rear area, not to mention that it obviated any strategic bombing missions.

In 1941 the Germans were ill prepared to sustain the losses inflicted by the tenacious Soviet resistance. After nine days of war, 699 German aircraft, including 286 bombers, had been lost. It is highly remarkable that the Soviet claims during the same period—613 German aircraft shot down by fighters and 49 by AAA—are so close to the actual Luftwaffe losses.28 While this process of attrition continued, the Soviets manufactured the mass quantities of war equipment that would eventually bring down Hitler’s Third Reich.