Fighter Combat Over Smolensk

Nothing seemed to stop the German Army Group Center as it continued eastward on both sides of the highway to Moscow during the first days of July 1941. On the northern flank. General Wolfram von Richthofen dispatched the bulk of his Fliegerkorps VIII to provide close support for Panzcrgruppc 3, which was rushing Coward the city of Vitebsk, to the north of the highway to Moscow.

To render the operational command more effective, a spedal air command, Nahkampfftihrer, led by Oberst: Martin Fiebig, was established by Fliegerkorps II. Comprising the Bf 110 “high-speed bombers” of SKG 210 and the Bf 109s of JG 51, Nahkampffiihrer w-as employed to provide close support of Panzcrgruppe 2 as it advanced from the Berezina bridgehead on the southern flank of Army Group Center.

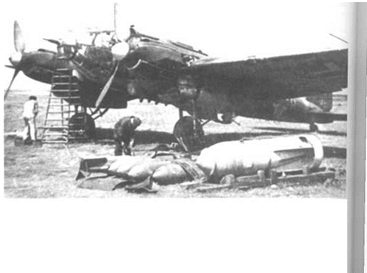

While delivering highly successful strikes against the Soviet defensive positions, the close support from the air also had the effect of lowering the willingness among the German ground troops to fight without air cover. Luftwaffe Oberst Hermann Plocher noted that the army at: this point “had become outrageously spoiled by the continous employment of Luftwaffe units in direct support on the battlefield."” Ground troops started showing a tendency to retreat prematurely whenever confronted with any serious Red Army resistance if Luftwaffe aircraft were not: present. The ground troops frequently complained that the liaison with the close-support units of the Luftwaffe did not work quickly enough. General von Richthofen replied that the army should understand that every sortie required time; planes had to be refueled, loaded with bombs, and then flown to the

new objective. He wrote that “the Army refused to realize that the Luftwaffe could not be dribbled out at all places but must be concentrated at major points."

Six fresh Soviet armies were establishing a defense position along the Dnieper River, but they were considerably slowed and hurt by Luftwaffe bombings. The medium bombers of Luftflotte 2 were directed against the communication lines in the Soviet rear area; roads, railways and railway junctions were the main targets. Simultaneously, the Soviet airfields were attacked again and again.

With fewer than five hundred combat aircraft divided among seven air divisions remaining in VVS – Western Front after the air battle with JG 51 over Bobruysk on the last day of June, there was a desperate need for reinforcements on the Soviet side. However, as the front line spread to the east, the air war reached into the operational area of the crack 6 ТАК of the Moscow PVO. The 6 IAK included units equipped with aircraft designer Aleksandr Yakovlev’s first fighter, the superb

Yak-1. On July 1 the Stavka directed the special 401 IAP, assigned to test new aircraft types, to the Berezina – j Dnieper front The commander of this unit, American – j born Podpolkovnik Stepan Suprun, was one of the most : experienced Soviet fighter pilots at that time. Awarded! the Golden Star as Hero of the Soviet Union in 1940, he I tested more than a hundred aircraft types, the last one— ? as late as June 29, 1941—a modified Yak-1 M.

Suprun was a friend of aircraft designer Aleksandr! Yakovlev. The last time they met, on June 29, Suprun f told Yakovlev that he wished to go to the front as soon I as possible and “test the German fighter aces.”

With the arrival of 6 LAK and Suprun’s elite unit, Щ the previous instruction to all VVS fighter pilots to avoid ft combat with the Bf 109s was abolished. A serious В attempt was made to actually challenge the Luftwaffe – I including the Jagdflieger—for air supremacy. 6 LAK and 1 Suprun’s pilots were immediately throwm into fierce air j combat. The pilots of 401 IAP put up five to six sorties Щ on July 1, claiming several kills. Suprun triumphed by Щ

knocking down four on this his first day of combat with “the German aces." On this day, KG 53 Legion Condor under command of Oberst Paul Weitkus lost four He Ills.

Also on July 1, Leytenant Nikolay Terekhin of 161 1AP scored three rather unusual aerial victories. Terekhin’s flight of six I-16s had just landed at Minsk Airdrome after a combat mission when a formation of German bombers, probably He Ills of KG 53, appeared and started dropping bombs on the base. Despite having emptied his ammunition on the earlier sortie, Terekhin took off in the middle of the raid. His little Polikarpov fighter climbed rapidly. Terekhin aimed at a bomber on the right side of a flight formation and without hesitating started cutting its tail fin with his propeller. With the rudder cut into pieces, the German aircraft flipped over to the left and hit the flight leader’s aircraft. This bomber in turn veered to the left and collided with the last aircraft of the Kette. It was a fantastic scene. In the next ; minute, all four planes—the three Luftwaffe bombers and

the I-16-went down. Six or seven parachutes opened in the sky, but the combat was not over. On their way to the ground, the German airmen and Terekhin started j firing at each other with their small flight pistols.

Meantime, a group of Bf 109s appeared and started attacking the I-16s that had followed Terekhin aloft. One or two l-16s went down in flames as the remaining German bombers withdrew to the west. A bit farther away If the He Ills came under attack by another flight of 1 1-16s.

As they landed in hostile territory, the parachuting і German bomber fliers were disarmed and tied up with a rope by members of a local collective farm. As if taken from a scene from a Western movie, Terekhin appeared in General-Mayor Georgiy Zakharov’s 43 1AD hcadquar – K ters with his pistol in one hand and the rope with the tied-up Luftwaffe airmen in the other.

The sudden appearance of large numbers of modern Soviet fighters stunned the Germans. “The enemy still ^ possesses remarkably great numbers of bombers and fighters” was noted in the war diary of Oberstleutnant Werner if; Molders’s JG 51 on July 2, 1941. On that day the ( medium bombers of Luftflotte 2 dispatched a large-scale effort against the airfields around Gomel, south of Army і Group Center’s right flank.

The Soviet tactic was to fight to win time. It was I derided that Smolensk, a main city on the road to Moscow, was to be defended at all costs. On July 3, German reconnaissance aircraft reported, “Strong enemy tank column, at least one hundred heavy tanks, heading westward for Orsha.” Orsha, on the Dnieper bend halfway between Borisov and Smolensk, would become the scene of a major tank battle during the next few days. General von Richthofen immediately employed his Stukas against this threat while the Do 17 medium hombers of KG 2 and 11I./KG 3 raided the supply lines of these Soviet troops.

As a way of maximizing the pressure on the Red Army, the medium bombers of Luftflotte 2 were committed to both day and night bombing. The Soviets countered by launching fighters at night, though with very primitive methods—guided only by eyesight and searchlights. During a mission on the night of July 3-4, 160IAP lost its commander, Mayor Anatoliy Kostromin. Flying an 1-153, he attempted to attack an He 111 of KG 53, visible in the searchlight beams over Smolensk but was himself shot down by the gunners of the bomber.

On July 4 the large tank concentration spotted by the Luftwaffe reconnaissance—a crack Red Army division equipped with some of the new T-34 tanks, superior to anything the Germans could mobilize at that time – clashed with the German 17th Panzer Division west of Orsha. The last remaining ground-attack planes available to the Soviet Western Front were dispatched to provide the T-34s with air support. Few of the planes returned.

One of the most famous Soviet ground-attack pilots of World War II, Mladshiy Leytenant Mikhail Odintsov, twice awarded Hero of the Soviet Union (once for shooting down two German aircraft while flying an 11-2), flew an Su-2 in 820 ShAP and narrowly escaped getting killed: “Four Me 109s attacked us. Both my gunner and myself were seriously injured. We barely managed to land. Our plane was so shot up that it was classified beyond repair! But at least my navigator had shot down one Me 109.”9

The new WS tactic of actively seeking combat with the Jagdflieger proved to be a fatal mistake. To the young and self-assured German fighter aces, this mainly meant new opportunities for shooting down enemy airplanes. On July 4 Leutnant Erich Schmidt of 1II./JG 53 achieved his thirtieth victory’ by downing an 1-16. On that day another German fighter pilot claimed the life of Podpolkovnik Stepan Suprun.

After a successful dogfight over the front area, Suprun

|

remained in the air for a while in order to protect his landing comrades in the eventuality of a German raid. Suddenly two Ju 88s of KG 3, escorted by four Bf 109s of JG 51, dove out from the clouds. Suprun made a courageous attack and managed to shoot down one of the Ju 88s. In the next moment, his MiG-3 was attacked by the Bf 109s. One of the German fighter pilots scored a decisive hit and the MiG-3 fell vertically into a forest. The remains of this formidable fighter pilot were not found until twenty years later, but on July 22, 1941, Suprun was posthumously awarded his second Golden Star, thus becoming one of the first double Heroes of the Soviet Union. (During the war, seventy-four Soviet airmen were made double Heroes of the Soviet Union.)

The German equivalent of the Golden Star of the Hero of Soviet Union, the Knight’s Cross, was awarded to one of the aces of JG 51 on July 2—Leutnant Heinz Bar (nicknamed Pritzl because of his affection for Pritzl

candy bars). Bar, who had scored his thirtieth victory the same day, would develop into one of the outstanding 1 fighter aces of World War П. Although in almost constant trouble with his superiors due to a nearly total lack of military’ discipline, Bar showed tremendous skill in air combat. From the first day of war in 1939 until the final months in 1945, he flew approximately a thousand ties on all fronts, and achieved 220 confirmed victories, j including 96 on the Eastern Front and 16 while flying an Me 262 jet fighter.

On July 5 Bar increased his score with one MiG-3 and two DB-3s while his Geschwaderkommodore, thfi famous Oberstleutnant Werner Molders, bagged two MiG-3s and two SBs. With such adversaries, most Soviet airmen active in the summer of 1941 could not expect to survive long. In fact, the average life expectancy h the Soviet front-line air regiments during 1941 was not more than twenty-five missions, a few weeks of normal

Mikhail Odintsov was one of the most famous Shturmovik pilots of World War II, during which he was twice awarded the Golden Star of a Hero of the Soviet Union. The outbreak of the war in 1941 saw Odintsov as a nineteen-year-old mladshiy leytenant and Si – 2pilot. After recovering from wounds he sustained when his Su-2 was shot up by a Bf 109, Odintsov learned to fly the II-2 with considerable success. By the end of the war, Odintsov had paid bac< dearly for when he was shot down; he was credited with a total of twelve aerial victories, the highest score for any il-2 pilot during the war. (Photo: Seidl.)

combat activity. Several VVS units were completely obliterated during the air war in the Smolensk area.

Added to the losses in the air were the continued devastating results of the German air-base raids. Also on July 5, twenty-nine Do 17s of II1./KG 2 Holzhammcr and III./KG 3 Blitz claimed twenty-two Soviet aircraft on the ground during a raid against the airfield at Vitebsk. Only one German bomber, from KG 3, was lost.

The last hope for the Soviet army commander, General-Leytenant Pavel Kurochkin, was the new 11-2 Shturmovik. Regarded as the trump card of the VVS, the Il-2s of 61, 215, and 430 ShAP had

been kept in reserve during the first days of the war. But now 430 ShAP was rushed to the front to bolster the battered 4 ShAP.

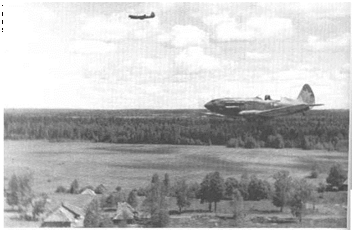

At dawn on July 5, 1941, a formation of nine Il-2s from 430 ShAP attacked the tank spearheads of the German 17th Panzer Division at Orsha. In spite of heavy fire from light AAA-several Shturmoviks received more than 200 hits, but none failed to return to base—they caused enough destruction and confusion to delay the German offensive on this sensitive sector for twenty-four hours, thus enabling the Soviet ground forces to reinforce their positions. 430 ShAP’s first combat mission was a total success.10

Other Soviet air units suffered worse. Raiding the airfield at Bobruysk on the same day, 4 ShAP lost two pilots, including the commander of 3 Eskadrilya, Kapitan Nikolay Satalkin. Nevertheless, 4 ShAP claimed a major success, and this won the unit commander, Mayor Semyon Getman, the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

But the results of the aerial combats were never onesided. On this July 5, both fighters of the alert Rottc of 6./JG 51 were shot down while pursuing Soviet bombers. The airfield of JG 51 at Bobruysk became the target of a sudden strafing attack by a group of I-16s. “Go get them!” shouted the Staffelkapitan, Oberleutnant Walter Stengel. Fcldwcbcl Georg Seidel and his wingman, young

Gcfreiter Anton Hafner, took off immediately. As the two Bf 109s climbed above the burning airfield, they could see no trace of the intruding Ishaks. Instead, three DB-3 bombers appeared. The two German fighter pilots heard the voice of the Staffelkapitan in their headphones: “Stay close together and attack! You’ll pick all three!” Armin Relling, the biographer of then-up-and-coming top ace Anton “Toni” Hafner, wrote:

But they didn’t pick anything. The Soviet airmen also had learned a great deal.

The German fighters were met with a strong defensive fire. Feldwebel Seidel’s aircraft was hit in the oil tank and the entire windscreen was covered with grease. Flying too low to be able to bail out, he jettisoned the canopy, and was sprayed with hot oil all over his face. With severe bums on his face, he managed to belly-land. Hafner was next in turn to receive the full brunt of the Soviet gunners’ attention. He saw a flash immediately in front of him, and for a moment he thought that an explosive grenade had exploded on his goggles. Then he saw the hole in the cabin glass.

Still he didn’t feel any pain, but he knew that the next hit would settle the fate of his machine. More instinctively than consciously, he glanced at his instruments and saw blood dripping from his glove.

He would have liked to retaliate, but a man must know his own limits. He radioed the ground control and requested the airfield to be cleared for an emergency landing. He noticed that he hardly could speak. Suddenly, he felt the pains in his face.

Nevertheless, he managed to undertake a perfect landing. His aircraft had barely stopped before the ambulance with the doctor braked next to him.11

Several aces of both sides played a dominant role during the increased struggle for air superiority that raged over the battlefield in the Rogachev-Orsha-Smolensk triangle. On July 6 a flight of Soviet fighters under command of Starshiy Leytenant Vladimir Shishov of 6 IAK intercepted a formation of eight Ju 88s. Shishov shot down one of them and forced the remaining seven bombers to turn away. At this moment German fighters appeared. Shishov managed to down one Bf 109 but was

As the main concentration of the air war spread to the east, the 6 IAK of ; I the Moscow Air Defense, which mainly consisted of pilots with above- ; I average training, was drawn into purely tactical operations. On July ЗІ I and 4, Mladshiy Leytenant Petr Mazepin of 111AP scored 6 lAK’s first to : і kills, an He 111 and a Ju 88. The Ju 88 claimed by 233 lAP’s Starshiy ; I Leytenant Vladimir Shishov, above, on July 5 was 6 lAK’s fifth victoiy..| I During the following fourteen months, Shishov would score twelve mors 1 I kills in 215 combat sorties. At the end of 1942 he was named a Hero of lithe Soviet Union. (Photo: Seidl.)

then jumped by another Bf 109, which damaged his air – j I craft before the German was driven off by Shishov’s wingman. During another encounter on that day, ; Leytenant Konstantin Anokhin of 170 LAP/23 SAD 1 sacrified his life. Intercepting five German bombers in I the Orsha vicinity, Anokhin destroyed one, but in |j return his own Yak-1 was shot down in flames. The Soviet fighter pilot crashed bis aircraft into a German j tank formation near the small village of Zubovo. In February 1943 he was awarded the title Hero of the Soviet 1 Union posthumously. After the war, a statue of Anokhin 1 I j was erected in Zubovo. On the German side, Leutnant | I Heinz Bar of 1V./JG 51 claimed two “Severskys”- probably ll-2s of 4 ShAP—on the same day.

One of the most successful Soviet fighter pilots of Я

the first years of the war, Ley tenant Vladimir (■Kamenshchikov of 126 LAP, drew his first blood during these air battles. Between June 22 and June 30, he participated in shooting down five enemy planes in the vicinity of Bialystok (one personal and four shared kills). On July 7 he destroyed a sixth, a Bf 109 possibly piloted by Leutnant Gronke of 2./JG 51, who was missing after Й low-level attack near Slobin.

к Oberstleutnant Werner Molders of JG 51 kept hunting m the skies. Returning from a meeting with Hitler at I fe Fflhrer’s headquarters, Wolfsschanze, in East Prussia (where he had received the newly instituted highest German military award, the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords), Molders brought down three Soviet fighters on July 9 followed by two more on the tenth, and a further ten during the following five days.

On July 10 Generaloberst Heinz Gudcrian decided to disengage his Panzergruppe 2 from the battle at Orsha.

|

|

Tvm of the top fighter aces of the Luftwaffe: Werner Molders (I.) and Walter Oesau. Both served with the Condor Legion in the Spanish Civil War, in which Molders emerged as the highest scoring German fighter pilot with fourteen confirmed victories. Molders is known as the inventor of the Rotte – Schwarm fighter tactic, and he personally proved its validity by scoring 101 victories by July 1941. He later became very popular as Inspector of the Fighter Arm but soon came into violent conflict with the Nazi leadership. On November 22,1941 he was killed in a flight accident. (Photo: Galland.)

Instead, he mounted an attack across the Dnieper River to the south of Orsha. On that day, Leytenant Kamenshchikov of 126 1AP increased his score to eight (including four shared) by downing a Ju 88 of KG 3. Kamenshchikov would amass a total of twenty individual and seventeen shared victories by August 1942, but he was killed in combat later in the war. In the same engagement in which Kamenshchikov achieved his eighth kill, 126 LAP’ s Mladshiy Leytenant Stepan Ridnyy shot down a second Ju 88 with his 1-16. In Stab/KG 2, the Do 17 piloted by Leutnant Bruno Berger was shot down by Starshiy Leytenant Mikhail Chunusov from a second MiG-3-equippcd crack test-pilot regiment, 402 IAP. On July 11 IV./JG 51 ’s Leutnant Heinz Bar scored his fortieth victory when he bagged two DB-3s near Bobruysk. Meanwhile, Mladshiy Leytenant Ridnyy destroyed an He 111, and on July 12, together with another pilot, downed two more Ju 88s, possibly from 5./KG 3, which lost three Ju 88s during attacks against Soviet lines of communication near Smolensk. Four weeks later, both Kamenshchikov and Ridnyy were made Heroes of the Soviet Union.

Also on July 12 Hauptmann Richard Leppla, the commander of I1I./JG 51, brought home the twelve-hundredth victory of Werner Molders’s Jagdgeschwader, of which more than 40 percent were credited against Soviet aircraft Guderian noted that wherever Molders’s fighters showed themselves, “the air was soon clear.” This was felt by three 1-16 pilots of 168 IAP who ran into four Bf-109s on July 12. Only one of these I-16s returned to base.

Between July 12 and 14 Guderian’s armored forces managed to break through the Soviet defense lines at the Dneiper River and surround the strong Red Army contingents at Orsha and Mogilev. To the south of Guderian’s main thrust, the Soviet Twenty-first Army launched a strong counterattack in the Bobruysk area, seized Rogachev and Zhlobin on July 13, and thus posed a serious threat to Guderian’s lines of communication. The entire ground situation appeared utterly contradictory. On the one hand, large columns of defeated Red Army contingents were moving eastward, retreating from Guderian’s powerful offensive, but on the other hand, other Soviet motorized columns were moving westward to support the counteroffensive. The tactical units under command of Luftflotte 2 were launched in “rolling attacks” against both these streams. Ulf Balke, the

|

chronicler of KG 2, noted that each mission was intercepted by Soviet fighters at this time. On July 13 the Staffelkapitan of 7./JG 51, Oberleutnant Hermann Staiger, was shot down and seriously injured.

Having recovered from the wounds sustained by a DB-3 gunner over Bobruysk, 6./JG 51’s Gefreiter Anton Hafner spotted three 1-153s in the air over the front on July 13. Hafner immediately went after the biplanes. To his amazement, he saw the three enemy pilots dive to the ground and land on a field. With the engines in their aircraft still running, the Soviet airmen quickly jumped out of their Polikarpov planes and ran toward a nearby forest. It took Hafner two passes to set all three I-153s on fire. That evening, he made the following remark regarding the three Soviet pilots in his diary: “So now they had to walk home.”12

1I1./JG 27 scored thirty-six kills between July 12 and July 14. On the latter date, Luftflotte 2 put up 885 sorties, mainly against enemy troop columns. Oberstleutnant Werner Molders once again triumphed, this time by violently sending three of the new Pe-2 bombers to the

ground. On this day also, Unteroffizier Hans Fahrenberger of 8./JG 27 was shot down behind the enemy lines. Fahrenberger was lucky to evade capture, and after a few days managed to return to his unit. Shot down in the same area on July 15, the Stuka ace in 8./StG I, Oberfeldwebel Wilhelm Joswig, had a similar experience, Joswig was captured by Soviet troops but was liberated by German soldiers six days later.

The fate of Joswig was overshadowed by a remarkable feat on the same day, when Oberstleutnant Werner Molders became the first fighter pilot ever to surpass the hundred-victory mark. In his enthusiasm over this achievement, Hitler instituted yet a new top military award, the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords, and Diamonds. Molders became the first holder of this extravagant distinction. Afraid of losing such a pearl from the Nazi propaganda machine, Hitler removed Molders from frontline service and appointed him the first Inspector of the Fighter Arm. Ironically, this young favorite of Adolf Hitler would turn away from the Nazi regime in disgust within three months.

On July 16, Luftflotte 2 carried out 615 sorties against the Soviet Twenty-first Army in the Bobruysk area, reporting the I destruction of 14 tanks, 514 trucks, 2 [ antiaircraft guns, and 9 artillery pieces, к Luftwaffe losses included the commander в‘of 6./JG 51, Oberleutnant Hans Kolbow, who was killed as he attempted to bail out from his damaged Bf 109 only sixty feet above the ground. On that same day the Soviets were forced to abandon I Smolensk.

On July 16, Luftflotte 2 carried out 615 sorties against the Soviet Twenty-first Army in the Bobruysk area, reporting the I destruction of 14 tanks, 514 trucks, 2 [ antiaircraft guns, and 9 artillery pieces, к Luftwaffe losses included the commander в‘of 6./JG 51, Oberleutnant Hans Kolbow, who was killed as he attempted to bail out from his damaged Bf 109 only sixty feet above the ground. On that same day the Soviets were forced to abandon I Smolensk.

I On July 17, Panzergruppe 2 reached і Yelnya, fifty miles southeast of Smolensk.

With this, another twenty Soviet divisions [ were surrounded in the Smolensk area.

In his enthusiasm over these victories, і Hitler awarded the commanders of I Panzergruppen 2 and 3, Guderian and Hoth, respectively, and the commander of Fliegerkorps VIII, General von

Richthofen, with the Oak Leaves to the Knight’s Cross. |: As an acknowledgment of the vital role played by

ihe close-support units of Luftflotte 2, the commanders I ofStG 2, Oberstleutnant Oskar Dinort, and SKG 210,

Major Walter Storp, were awarded with the Oak Leaves on July 14, 1941. Known as “Uncle Oskar,” forty-year – old Dinort was one of the most popular Luftwaffe unit commanders at this time. He became the first dive-bomber airman to be awarded the Oak Leaves.

The Soviet situation was growing increasingly desperate. At this point the terrible losses placed the Red Army in the central combat zone in qualitative as well ".s numerical inferiority. General – feldmarschall Fedor von Bock’s Army Group Center enjoyed a superiority of five to one in tanks and almost two to one in artillery, and Luftflotte 2 could muster twice as many serviceable aircraft as its Soviet opponents in this sector.

Despair spread among the Red Army soldiers and airmen. The shrinking number of Soviet aircraft operated under most difficult conditions, taking off from battered airfields littered with wrecks of planes destroyed in Luftwaffe raids.

On July 20 the WS-Western Front was down to 389 aircraft—103 fighters and 286 bombers. The combat figures for 410 BAP/OSNAZ are quite revealing: Having arrived at the Western Front with thirty-eight new Pe-2 bombers on July 5,

this unit carried out 235 sorties and lost 33 planes (22 to German fighters) in only three weeks’ time. 4 ShAP, the first 11-2-equipped unit, was reduced to ten aircraft and eighteen pilots—down from sixty-five on hand two weeks previously. Until the end of July, 4 ShAP counted fifty – five aircraft lost on combat missions, with two other planes receiving severe battle damage.11

After the first month of the war, the Luftwaffe reported the destruction of 7,564 Soviet aircraft It is difficult to verify this figure. Loss statistics generally should be handled with great care, particulary concerning the Eastern Front, where documents frequently were lost by both sides during chaotic retreats. VVS loss statistics show a lower figure. But by comparing official loss figures with the decrease in the number of aircraft on hand (including replacements), a large gap between VVS loss figures and the actual decrease in the number of combat aircraft is obvious. This “unaccounted decrease" figure for the period June 22-July 31 amounts to 5,240 combat aircraft. For instance, the officially registered loss figure for 64 LAD on June 22 was five aircraft destroyed in combat plus three or four in accidents. But of 239 aircraft (175 1-16s and 1-153s, 64 MiG-3s) on hand on June 21, fewer than 100 remained on June 23.

In fact, the total number of first-line aircraft in the VVS dropped from nearly 10,000 on June 22 to 2,516 (of which fewer than 1,900 remained serviceable) in mid – July—a decrease of about 7,500.

Desperate to save the situation, on July 16 the Stavka reestablished the old dual-command system-politically appointed commissars supervising the military commanders at every level of command. This move was extremely counterproductive. What the Soviets needed was more individual initative at the front, not an increased fear of reprisals.

The price paid by the invaders had also been considerable. During the two weeks between July 6 and July 19, the opening of the Battle of Smolensk, 477 Luftwaffe aircraft were destroyed or damaged on the Eastern Front After the first month of war with the USSR, total Luftwaffe losses on the Eastern Front amounted to 1,284 aircraft destroyed or damaged—nearly half the original force. By July 15 Oberstleutnant Werner Molders’s JG 51 had lost eighty-nine Bf 109s since the first day of the war on the Eastern Front. The number of serviceable German aircraft fell alarmingly. On July 22 Hauptmann Wolf-Dietrich Wilcke’s II1./JG 53 reported: “Frightening lack of aircraft!"14

Unremitting Soviet counterattacks in the air and on the ground had delayed the schedule for the offensive, resulting in heavy losses on both sides. Nevertheless, the two dead-tired armies continued to rain hard blows on one another. On July 19, Hitler issued his Order No. 33, calling on the overextended Luftwaffe to begin conducting terror raids against Moscow.