Just as the X Prize Foundation faced challenges to keep the prize going, the individual teams faced similar problems. The biggest of these was funding. It wasn’t so much of a technology challenge that the teams had to overcome—the technology to get into space had been around for a long time. The teams were not starting from square one. In fact, with modern materials and computers, a technical leap wouldn’t likely be the limiting factor.

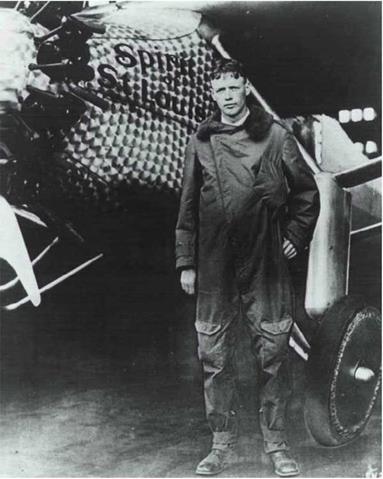

Rutan and his team certainly seemed to be in a very good position. “Some viewed him as the frontrunner,” Diamandis recalled. “Lessons of history are that sometimes the frontrunner doesn’t win. In the Orteig Prize for example, the frontrunner was Admiral Byrd, the first person to fly to the North Pole. He crashed on liftoff. This young upstart, unknown to the rest of the world, Charles Lindbergh, comes along and wins the competition.”

A total of twenty-six teams registered for the Ansari X Prize, representing seven different countries, but not every team that applied made it in. “We probably turned away about half the applications we received,” explained Diamandis. “We required the teams to really demonstrate to us the seriousness of their team and effort. They had to demonstrate by virtue of the people who were involved, the companies who were involved, and they had to show us the primary concept.

“We had numerous teams apply with antigravity and UFO technology. My answer was simple: ‘My office is on the second floor. If you can float up to the second floor, I’m happy to register you.’ ”

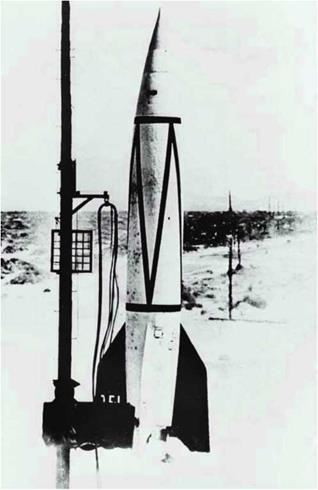

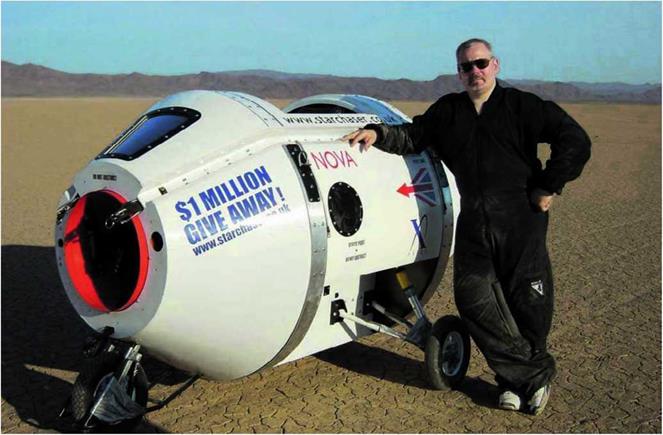

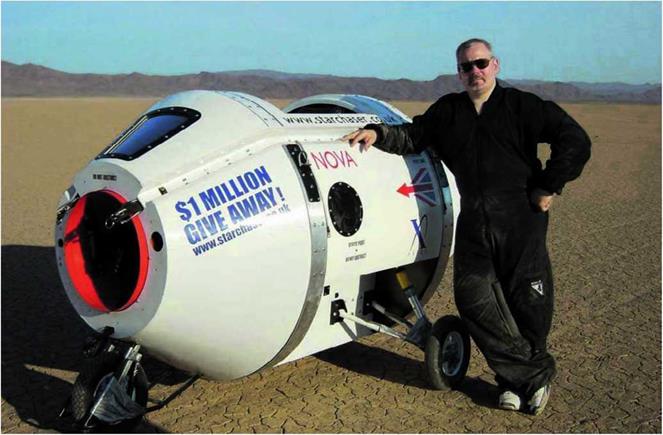

Some of the teams that competed did get vehicles into the air and performed flight tests to various degrees, while some hadn’t had the resources necessary to get their programs very far off the ground. Two of the top contenders were Steve Bennett’s Starchaser out of England and Brian Feeney’s da Vinci Project out of Canada, refer to figure 2.13 and figure 2.14, respectively.

“Steve Bennett was the first person to fly an X Prize vehicle, or a vehicle with X Prize logos on it, called Nova, which was the first launch in like thirty years out of the UK,” Diamandis said.

Launched on November 22, 2001, Nova weighed in at 1,643 pounds (747 kilograms). It was unmanned, but the capsule was designed to fit one person. Starchaser had actually developed and launched rockets beginning in 1993, well before the Ansari X Prize was announced, so it was one of the more established teams.

“I didn’t want to apply for the X Prize competition and come across as someone who was ill equipped to deal with it,” said Steve Bennett, the team leader of Starchaser. “It took me about a year to get all my ducks in a row. And we made the application, and Peter accepted it no problem.”

A bigger vehicle was still needed, since the Ansari X Prize required it to fit three people. “We went through a number of ideas and over the years the design evolved,” continued Bennett. “And what happened was it just got simpler and simpler and simpler. So, we

Ґ л

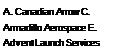

Fig. 2.13. Having launched over sixteen large rockets since 1993, Starchaser was one of the more experienced teams competing for the Ansari X Prize. Even after the Ansari X Prize, Starchaser rocket development continues.

Fig. 2.13. Having launched over sixteen large rockets since 1993, Starchaser was one of the more experienced teams competing for the Ansari X Prize. Even after the Ansari X Prize, Starchaser rocket development continues.

In 2007, Starchaser won a study contract from the European Space Agency (ESA) to further investigate reusable launch vehicles for space tourism. Courtesy of Starchaser Industries

V_________________ )

( ^

Fig. 2.14. To avoid the high cost of developing a ground-launched rocket

or a carrier aircraft, Brian Feeney’s da Vinci Project built the world’s largest balloon, capable of holding 3.70 million cubic feet (0.10 million cubic meters) of helium, to lift its Wild Fire rocket to a launch altitude of 70,000 feet (21,340 meters). Brian Feeney, the da Vinci Project

V___________________ J ended up with a very simple ballistic rocket. We discovered that the easiest and simplest and safest way to do this would be to just launch a ballistic rocket just like they launched Alan Shepard in back in ’61. Straight up, straight down, and a capsule that can carry three people. And that’s pretty much it.”

The rocket had three main components: a booster, which was the Starchaser 5 rocket powered by liquid oxygen (LOX) and kerosene fuel engines; the capsule, which was called Thunderstar; and the launch escape system.

Figure 2.15 shows Bennett standing next to the Nova 2 after piloted drop tests from 10,000 feet (3,050 meters) were conducted.

Bennett admitted, “The biggest challenge was, I guess, raising the finances, because the technology to do this kind of thing has been around since the 1950s, possibly even the 1940s.”

So, the team had to be creative. Back in 2000, they had pre-sold two of the seats for when they would first attempt the Ansari X Prize.

Ґ

Ґ

Fig. 2.15. Steve Bennett stands next to Nova 2, which was drop tested from an altitude over 10,000 feet (3,048 meters) to test the parachute-recovery system. For each test, a pilot manned the capsule, which was then dropped out the back of a cargo plane. Courtesy of Starch a ser Industries

v______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Bennett said of the two prospective passengers, “They wanted to basically support the project. And they wanted to fly on the first flight. We got three seats in the capsule. The only condition they made was, ‘Here’s the money, Steve. We’ll give you the money. We’ll give it to you up front, and we’re not even going to come back to you. We don’t care whether it takes a year or ten years. You tell us when it’s ready. We’re not going to hassle you. There is only one condition.’ And the one condition was the third seat had to be occupied by me. Okay. So, they knew I wasn’t a nutcase. They knew that I wanted to do this project and that I wanted to come home to my family.”

The competition really began to heat up midway through 2004, when two teams each secretly notified the X Prize Foundation that they were going for it. Diamantis recalled, “People have to give both confidential notice within 120 days and public notice within 60 days of their attempt to fly. So, we had gotten confidential notice of Rutan’s flight date, and then a few weeks later we got confidential notice from Brian Feeney that the da Vinci Project was going to attempt a flight.

“We thought for a moment we might have to mount flight competitions in two separate nations, and funding that and doing a good job of judging was going to be a challenge for us.”

Feeney, who had an aerospace company in the 1980’s that did life – support systems, read an article about the announcement of the Ansar і X Prize while living in Hong Kong. “That was the catalyst for me,” he said. “I stopped what I was doing right away at the time.” Feeney had constantly looked for opportunities that would take him to space. He rallied one of the largest volunteer efforts for a technology project in Canadian history while using a very unconventional approach to reach space. At first he looked into developing a carrier aircraft like Scaled Composites had done. “We wanted to do that even before we knew what they were doing. But the cost to do that was just prohibitive. We knew we’d be challenged just to get the money to build the spaceship itself,” Feeney said.

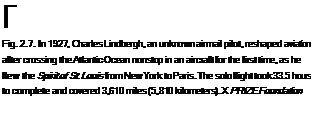

“A ground-launched vehicle required about four times as much energy, thrust, everything else, compared to an air-launched vehicle, whether it was balloon, as in our case, or an aircraft or whatever

ґ

Fig. 2.16. Teams had to give a 120-day confidential notice to the X Prize Foundation that they were going to make an attempt at the Ansari X Prize. As the deadline loomed, Scaled Composites gave its secret notification, and a few weeks later, the da Vinci Project also gave notice. The da Vinci Project finally got a big chunk of funding from GoldenPalace. com, but it proved to be too late in the game. Brian Feeney, the da Vinci Project

v______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

v______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

means of getting to that altitude. At the end of the day, I thought the balloon-launch system was a good compromise with the much higher cost of developing a ground-based launch rocket.”

A rocket called Wild Fire, pointing up at 75 degrees, would be tethered to the world’s largest reusable helium balloon. Made of polyethylene, the balloon, measuring in at 150 feet (46 meters) in diameter and 200 feet (61 meters) in length, could contain 3.70 million cubic feet (0.10 million cubic meters) of helium. It would only be 15 percent full at liftoff but would expand as it ascended. The da Vinci Project had successfully tested a scaled-down version of their launch balloon before constructing the final launch balloon.

Figure 2.16 shows the Wild Fire rocket at only 80 percent complete. At an altitude of 70,000 feet (21,340 meters), which is higher than any launch aircraft could fly, Wild Fire would detach and use a hybrid fuel rocket engine to soar into space.

“I never felt in the long run that it was an ideal commercial proposition, because the balloon is subject to weather and a multiplicity of things. But it is a cost-effective way for a short program to demonstrate viable technology,” Feeney said.

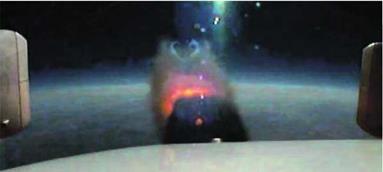

Fig. 8.9. SpaceShipOne reached an apogee of 211,400 feet (64,430 meters), and the video camera in the tail boom recorded the feather in the extended position. While high above Los Angeles, SpaceShipOne was technically not in space, even though the curvature of Earth can be clearly seen. However, the curvature is somewhat exaggerated due to the auto focus lens used. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, video capture provided courtesy of Discovery Channel and Vulcan Productions, Inc.

Fig. 8.9. SpaceShipOne reached an apogee of 211,400 feet (64,430 meters), and the video camera in the tail boom recorded the feather in the extended position. While high above Los Angeles, SpaceShipOne was technically not in space, even though the curvature of Earth can be clearly seen. However, the curvature is somewhat exaggerated due to the auto focus lens used. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, video capture provided courtesy of Discovery Channel and Vulcan Productions, Inc.

f ^

f ^ г———————————————————-

г———————————————————-

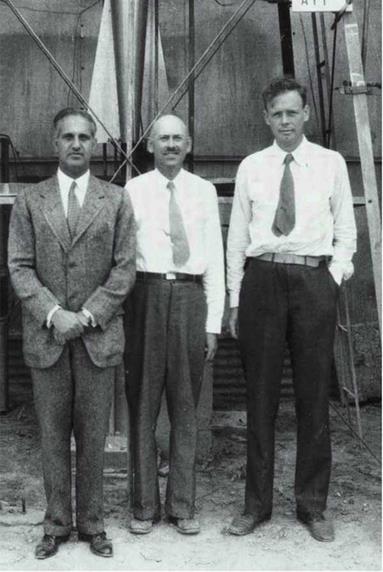

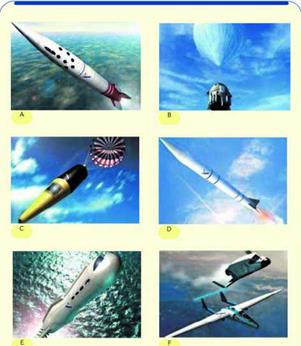

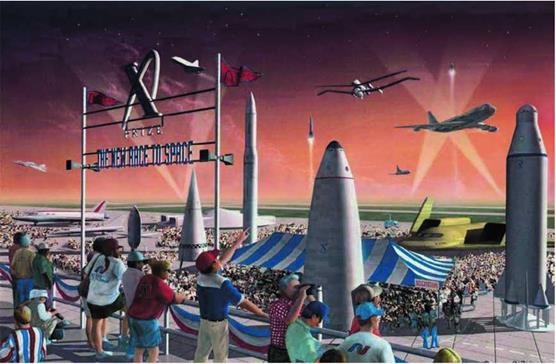

Fig. 2.11. The vision of Peter Diamandis and the X Prize Foundation was to rekindle the public’s interest in space and foster the development of private spacecraft that would open the door to the stars for more than just the very limited number of astronauts from government-sponsored programs. X PRIZE Foundation

Fig. 2.11. The vision of Peter Diamandis and the X Prize Foundation was to rekindle the public’s interest in space and foster the development of private spacecraft that would open the door to the stars for more than just the very limited number of astronauts from government-sponsored programs. X PRIZE Foundation

Fig. 2.13. Having launched over sixteen large rockets since 1993, Starchaser was one of the more experienced teams competing for the Ansari X Prize. Even after the Ansari X Prize, Starchaser rocket development continues.

Fig. 2.13. Having launched over sixteen large rockets since 1993, Starchaser was one of the more experienced teams competing for the Ansari X Prize. Even after the Ansari X Prize, Starchaser rocket development continues.

Ґ

Ґ