1927: New York to Paris

In 1919, Raymond Orteig created the Orteig Prize for the first nonstop flight across the Atlantic Ocean from New York to Paris or from Paris to New York. Orteig, born in France, owned hotels in New York City. Prizes had been enticing aviators and aircraft makers for a decade now. Newspapers sponsored them because it gave their readers something exciting to read. Businesses sponsored them because they saw financial opportunity.

Aviation technology was not up to the challenge, and Orteig had to extend the deadline of the prize. Come 1926, still no one had claimed the prize. Only one team made an attempt, but they crashed on takeoff.

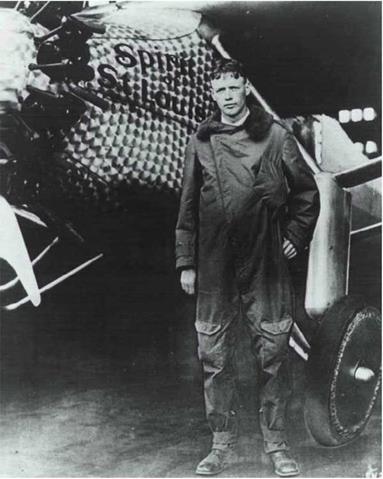

On May 20, 1927, with only 20 feet (6 meters) to spare, the Ryan NYP Spirit of St. Louis cleared the telephone wires a short distance from the edge of the runway at Roosevelt Field on Long Island. Charles Lindbergh, shown in figure 2.7, had just lifted off for his first solo attempt at crossing the Atlantic Ocean. Several failed attempts had already been made by other competitors by now. Nine teams were in the race to win the $25,000 Orteig Prize. Four men had died trying, and two others, setting out together right before Lindbergh, were lost over the Atlantic.

To make the journey, Lindbergh would have to strip the plane down to the bare minimum to maximize the amount of fuel he could carry. Table 2.1 shows the specifications of the Spirit of St. Louis. So much of the aircraft was gas tank, by design, that Lindbergh had to use a periscope to see directly ahead of the aircraft because a gas tank in front

г———————————————————-

г———————————————————-

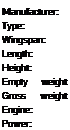

Table 2.1 Spirit of St. Louis Specifications

Ryan Airlines Company highly modified M-2 46 feet (14 meters)

27 feet 8 inches (8 meters)

![]()

|

9 feet 10 inches (3 meters) 2,150 pounds (975 kilograms) 5,135 pounds (2,330 kilograms) Wright Whirlwind J-5C 223 horsepower

![]()

Ґ Л

Fig. 2.8. The Spirit of St. Louis was specially designed by Charles Lindbergh to make the transoceanic flight. Much of the aircraft was a fuel tank, leaving little room for anything else. Lindbergh had to use a periscope to see in front of the airplane, and he elected not to bring a parachute or radio, to save weight. NASA-Langley Research Center

V__________________________________________ У

of the cockpit blocked the view forward. In a plane that weighed 2,150 pounds (975 kilograms) empty, it carried 451 gallons (1,710 liters) of fuel for a total takeoff weight of 5,135 pounds (2,330 kilograms).

Back in 1927, if you went down in the water, you were gone. There was no satellite tracking, there were no helicopters or airplanes that you could signal. There was no radar. And shipping was nothing like it is today, so rescue from a nearby vessel was highly unlikely. When Lindbergh got behind the controls of that plane and took off, he was all alone with only the vastness of the Atlantic Ocean more than willing to catch him if he fell. And there was less than just a slim chance of him not making it back.

So, the Spirit of St. Louis, shown in figure 2.8, didn’t have a radio, navigational lights, or gas gauges. Lindbergh didn’t even bring a parachute. A radio didn’t do any good over the middle of the ocean and, back in those days, was a lot of weight. The same held true for the navigational lights when the wiring was also factored in. Even gas gauges were redundant, since there would not be much he could do about it if the tanks went dry. But the reverse argument could be made. Each of these could help his chance of survival under some specific circumstances. What if a ship was nearby? Lights and a radio could certainly help. What if he was over land? He should be able to make an emergency landing, but there were circumstances where

bailing out was not out of the question. Lindbergh had to balance the potential benefit of each safety item with the problems he would potentially face if he ran out of fuel. And that’s how he decided.

“He was thinking his way all the way around the problem, though,” said Erik Lindbergh, the grandson of Charles Lindbergh. “I think he minimized every possible risk he could except for lack of sleep. And if he had had a good seven hours worth of sleep, he would have really changed his risk factor.”

Lindbergh didn’t even use a typical leather pilot’s seat. Instead, he used a wicker chair. He did, however, equip himself with four sandwiches, two canteens of water, and an inflatable, rubber life raft.

Lindbergh believed that for a multi engine aircraft, there was only a greater risk of an engine failure, even though most of the other competitors were using that type of aircraft. Today, a Boeing 767 flies overseas with only two engines. If one fails, it still has enough power to reach land by either turning around or by continuing on, whichever distance is shorter. That wasn’t necessarily the case for the multi – engine aircraft of that time.

“He was doing things like cutting the corners off of his map, which is really a negligible weight,” said Erik Lindbergh. “And yet when you look at the competitors, some of them had champagne and croissants on board so they could party when they got there. But they never made if off the ground. So, attention to detail and reducing the risk factors was critical to him surviving the flight.”

Charles Lindbergh became an instant international hero on the evening his wheels touched down in Paris. And people’s interest in aviation exploded. Charles Lindbergh said, “I was astonished at the effect my successful landing in France had on the nations of the world. To me, it was like a match lighting a bonfire.”

Erik Lindbergh said of his grandfather’s accomplishment, “Before he flew across the Atlantic, people who flew in airplanes were known as barnstormers and daredevils and flying fools. And after he flew across the Atlantic, people who flew in airplanes were known as pilots and passengers. It truly was a paradigm shift if there ever was one.”

As a result of this new popularity, referred to as the Lindbergh boom, in the United States the number of applications for a pilot’s license tripled and the number of licensed aircraft quadrupled during 1927. The number of passengers flying aboard U. S. airlines also dramatically increased from 5,782 in 1926 to 173,405 in 1929. Nowadays, the aviation transportation sector is a $300 billion industry.