Peter Diamandis

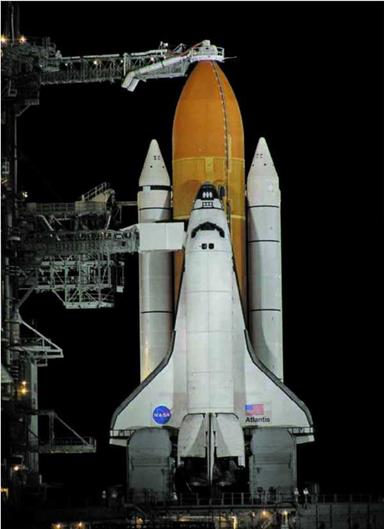

Like many people, Peter Diamandis’ fascination with space began back when he was a child. But unlike many people, he has not stood idly by waiting for the stars to come to him. His obsession with the point where gravity loses its touch, and the places beyond, firmly took root while he was an aerospace engineering student at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He had the chance to meet astronauts-in-training back then, but this forced the realization that his chances of becoming an astronaut himself were remote and that even if he did make it as one, he would fly to space maybe twice in a decade. Figure 2.4 shows Diamandis as SpaceShipOne made its way to space on October 4, 2004.

The government space programs do work well in specific ways, but very few people will ever get the chance to go up. “That wasn’t my vision of spaceflight,” Diamandis said. “I wanted to go as a private pioneer in my own ship whenever I wanted to go.”

Dennis Tito spent $20 million to fly to the International Space Station (ISS) aboard a Russian Soyuz in 2001, becoming the first

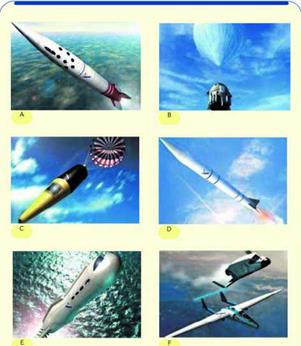

![]() B. IL Aerospace Technologies D. ARCA

B. IL Aerospace Technologies D. ARCA

F. Suborbital Corporation

Fig. 2.3. The competitors pursued many different approaches, although not every one managed to launch hardware. Concepts were either ground-launched or air-launched, and while most were rockets, many were space planes, with the exception of one flying saucer that would ride upon "blastwave" pulsejets. The air – launched vehicles were either carried or towed by an aircraft or lifted by a giant balloon. The methods of reentry were just as varied. X PRIZE Foundation

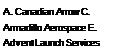

Fig. 2.5. Atlantis, Discovery, and Endeavor are the remaining three operational Space Shuttles. First launched on April 12, 1981, exactly twenty years after Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin’s first-ever spaceflight, the Space Shuttle had been the only U. S. vehicle to carry people into space for twenty-three years prior to the spaceflights of SpaceShipOne. Six Space Shuttles were built, although the first Space Shuttle, Enterprise, never reached space. In 1986, Challenger exploded during liftoff, and in 2003, Columbia broke apart during reentry. Dan Linehan

Ґ

Fig. 2.4. Peter Diamandis, the founder of the X Prize Foundation, gives the thumbs up as SpaceShipOne makes its way up to space during the second Ansari X Prize flight.

After reading The Spirit of St Louis by Charles Lindbergh, Diamandis was inspired to create a space prize modeled after the early aviation prizes.

Dan Linehan

f ^

f ^

Fig. 2.6. Thousands and thousands of space enthusiasts crowded into the high desert of Southern California to watch the spaceflights of SpaceShipOne as Mojave Airport transformed into a spaceport. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, photograph by David M. Moore

v___________________________________________ /

paying space tourist. Diamandis has reported that the cost to fly the Space Shuttle, shown in figure 2.5 preparing to launch to the ISS, has ranged from $500 million to $750 million for just one flight, of which propellants make up only 1 percent of that cost. These figures keep the gate to the space frontier shut pretty tight for most people. There just had to be another way.

While flying together over the Hudson River in 1994, Gregg Maryniak, a longtime friend and business partner, wondered when Diamandis would also get his pilot’s license. Diamandis had already stopped and started several times. This was unusual, considering Diamandis’ deep desire for space. One might expect that for someone with dreams of traveling among the stars, a pilot’s license was a good thing to have. But as history continues to remind us, the shortest distance between point A and point В is not necessarily a straight line. Diamandis was far too consumed with what was well beyond where the air is thin.

“Gregg asked me if I had ever read The Spirit of St. Louis,” Diamandis said. Maryniak had explained that he received the book as a gift, and it helped motivate him to finish his pilot’s license. Shortly after their flight, Maryniak gave a copy of The Spirit of St. Louis to Diamandis. But if anything, the book proved to sidetrack Diamandis, resulting in the unanticipated consequence of drastically changing not only how people reach space but also who gets to go.

“As I read that book, I had no idea that Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic to win a prize and that nine different teams had spent $400,000 to win the $25,000 prize,” Diamandis said. “And by the time I finished reading the book, the whole idea of the X Prize had come to mind.”

What Diamandis realized was that a prize could be the catalyst needed for the development of a new breed of spacecraft that could demonstrate the public’s desire for commercial spaceflight. “We needed a paradigm shift,” Diamandis said. “People had become so stuck in their way of thinking that spaceflight was only for the government—only largest corporations and governments could do this—it could never be done by an individual. This thinking was paralyzing us, and that was what I was trying to change.”

When Lindbergh made his famous crossing, the airplane had been in existence for a little more than two decades. It was still a novelty. Some enterprising individuals foresaw the economic advantages of aviation, while others stoked the fanfare and fervor. As a result, hundreds of aviation competitions were established to see who could fly the farthest, the fastest, the highest. It was as much about pushing the limits as it was about drawing boundaries where none had ever existed.

At a time when aviation was in its infancy, prizes and competitions put its growth on afterburners. And during these times, people could look in the mirror and see themselves in the cockpit, goggles drawn and wrapped in a scarf, without having to use too much imagination. Although some of the flyers were wealthy and privileged and others had renown and notoriety, Charles Lindbergh, an airmail pilot, and others like him, proved aviation was in reach of the common person.

Diamandis saw this vision, only with rocket ships and space helmets. His passion was contagious. He energized many talented and dedicated people who joined this march toward space, contributing thousands and thousands of volunteer hours along the way. Figure 2.6 shows the crowds who gathered to share in this vision.