Science and conflicts

EARLY DAYS

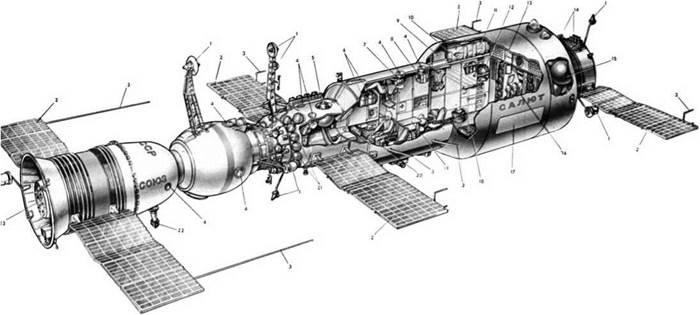

The first few days on Salyut were reserved for reconfiguring the station’s systems, checking the equipment, starting the scientific investigations, and allowing the crew time to adapt to their new environment. Salyut was considerably more complex than any previous manned spacecraft, with more than 1,300 individual instruments and in excess of 1,200 kg of scientific apparatus.

The Soviet press, television and radio reported enthusiastically this latest success of the manned space programme – the official line was that the Soviet Union had never participated in a race to beat the Americans to the Moon, it was concentrating on space stations to conduct scientific research and benefit the national economy, at which it clearly led the way.

MEDICINE ON SALYUT Day 3: Tuesday, 8 June

The second day for the cosmonauts on Salyut started at 1 a. m. on 8 June, when the station entered the Soviet communication zone. After breakfast, they checked the life support systems and made a start on preparations for the scientific programme. At 11.02 a. m., the cosmonauts initiated a manoeuvre to raise the orbit to 239 x 265 km with a period 89 minutes. With Salyut’s systems confirmed to be in good order the Soyuz was powered down, since its interior would be ventilated by the station’s life support system. In operating the complex station for the first time, the cosmonauts made several mistakes. For example, because they forgot to disable the docking regime, they had a problem when they first attempted to reorientate the station.

Daily life on board Salyut involved six major activities:

• the flight programme;

• morning hygiene and toilet;

• physical exercise;

• four meals;

• individual rest time; and

• an 8-hour sleep.

The flight programme included the control and maintenance of the station and its systems, the scientific equipment and investigations (the schedule included almost 140 specific experiments), radio communications and TV broadcasts, photographic sessions, and other tasks for flight operations. Exercise was of crucial importance in weightlessness. In addition to 2 hours per day exercising on the treadmill and with a chest expander, each man was to spend 30 minutes light ‘walking’ on the treadmill prior to retiring. Many lessons had been learned from the 18-day flight of Soyuz 9 in 1970, and the complex for physical training (KTF) was more substantial than the one available on that mission. The gravitational load imparted by the KTF on Salyut during physical exercise was 50 kg. On ‘sports’ days, each man had three exercise sessions in a 24-hour period: two of 75 minutes and one of 30 minutes. The flight plan allowed each man 2 to 2.5 hours per day of leisure time, which he could spend as he wished: resting, reading a book, observing the Earth, taking photographs or preparing for a forthcoming experiment. Every seventh day was a ‘weekend’ for the entire crew. The three men were to follow a phased sleep pattern in order that there would always be at least one man on duty, and at least one resting.

Day 4: Wednesday, 9 June

From 3 p. m. on 8 June to 1 a. m. on 9 June Salyut was out of the communication zone. After their morning toilet and breakfast, for the first time the crew exchanged their flight suits for the ones named ‘Athlete’ but irreverently known as ‘penguin’ suits.1 These suits were designed to impart loads on certain muscles to simulate the forces experienced in everyday life on Earth, in the hope that this would minimise the deterioration of muscles and bones during a long period of weightlessness.[67] [68] The cosmonauts used part of a communication session to demonstrate the suits, and to thank the designers. A system of supports and elasticated straps were attached to the wearer, as it were, by rigid soles and shoulder straps. The plan called for each man to wear his suit only for 40 to 60 minutes, 3 to 6 times per day, while working. They initially had some difficulty in moving their arms and legs while compressed by the elastic, but soon found the suits to be so comfortable that they asked to wear them all day, and later became so used to them that they slept in them as well.

On this day the cosmonauts also began to use the treadmill, but when it was noted that the vibrations which were transmitted through the station’s structure caused the solar panels and antennas to ‘flap’ with an amplitude at their tips of about 5 cm they were asked to use the treadmill only for short periods.

They started the scientific work by measuring the radiation level inside the station and the flux of micrometeoroids in space around the station. In addition, they tested the wide-angle periscope provided to enable Salyut to be precisely aligned relative to the Sun and the planets. At 10.06 a. m., Dobrovolskiy and Patsayev fired Salyut’s engine again to raise the orbit to 259 x 282 km. Although the atmosphere at orbital altitude is rarefied, it can impart a significant drag force that progressively reduces a satellite’s orbit, finally causing it to burn up. As the drag was greatest at the lowest point of the orbit, the manoeuvres were designed to raise this altitude. Reducing the rate at which the orbit decayed would extend the interval before another manoeuvre was required.[69] Although the initial engine firings were costly in terms of propellant consumption, in the long term this strategy made sense.

8.29 a. m.

Dobrovolskiy: “Last night I adjusted the orientation prior to stabilising the station; it is easy to control the spacecraft, it responds very well.’’

Volkov: “I’m doing a rotation according to the programme. The engines are firing smoothly. Viewing through the porthole by the right-hand command post, I can see the red-hot jets. I’m controlling the orientation; the jets are working and everything goes well.’’

10 a. m.

Volkov: “The engine is switched off. I’m tracking the time.’’

Zarya: “We understand.’’

Volkov: “A slight vibration. The machine vibrates.’’

Dobrovolskiy: “The engine was fired for 73 seconds. The integrator was switched off.’’

Patsayev: “The engine’s parameters are normal.’’

Zarya to Dobrovolskiy: “We understand, Yantar 1. Telemetry confirms that the engine fired for 73 seconds.’’

11.44 a. m.

Zarya: “In answer to your question about the ‘penguin’. The metal tail should be above your knee. You can regulate its height with the hidden cord in the lower part of your knee. To eliminate unpleasant feelings caused by the tail, move it parallel to the leg.’’

Volkov: ‘‘Yantar 1 is now feeling excellent in his ‘penguin’ suit.’’

In his notebook that day, Patsayev wrote up his first astrophysical observations, and made some suggestions for how to improve the design of future stations.

From Patsayev notebook:

The stars are almost invisible on the daylight portion of the orbit, even when observing through the porthole on the side facing away from the Sun. Only

|

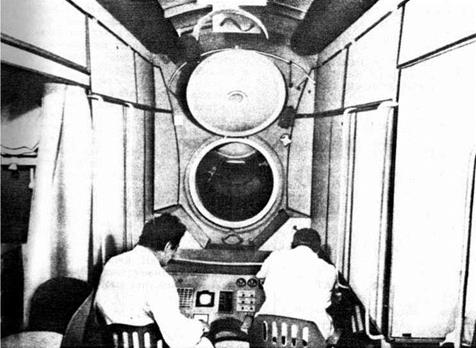

Two bearded cosmonauts on the Salyut space station, Dobrovolskiy and Volkov check instructions for the next scientific experiment in the narrow part of the main compartment. The large white cone in the background houses the main scientific equipment, which could not be used because its protective cover had failed to release following orbital insertion. |

Sirius and Vega can be seen. After sunset, the stars do not twinkle until their

line of sight is close to the Earth’s horizon.

Remark No. 1 – Add a protective cover for the button on the control handle.

Remark No. 2 – Modify the hermetic seal of the rubbish bags.

At 3 p. m. on 9 June, on the 38th orbit with the crew on board, the station left the communication zone.

Day 5: Thursday, 10 June

One of the primary tasks for this first crew was to determine the degree to which the human body (and indeed other organisms) were influenced by long-term exposure to weightlessness.

The crew were to have a detailed medical checkup every five days. This involved taking blood samples and electrocardiograms, and checking the composition of their bone tissue, in particular of their shins. The procedure was more sophisticated than on previous flights. For instance, whereas only the rate of breathing had previously been measured, now this was augmented by measurements of the volume and speed of inhalation and exhalation, and the overall lung capacity. In addition, the arterial blood pressure and the speed of pulsation waves through the arteries were measured by two separate methods. On Day 5 Patsayev took blood samples of all three men for the first time. He was to repeat this several times during the flight. Placed on the surface of filters, the samples were stored at reduced humidity in hermetic probes. After Soyuz 11’s return to Earth, doctors determined how the levels of sugar, urine and cholesterol varied in each man’s blood during the mission. The sugar level was normal in the blood samples taken during the first and third weeks, but increased in the fourth week just before the cosmonauts left the station. There was an increase in the level of urine in the blood of all three men owing to the manner in which their kidneys adapted to weightlessness. There was no detectable change in the level of cholesterol.

One of the most significant hazards of long-term exposure to weightlessness is the leaching of calcium from bones into the bloodstream, with possible implications for the kidneys. A special instrument was designed to investigate changes in the bones of the cosmonauts. Each day, every crewmember would place a medical belt around his chest. Before doing so, he would smear cream on his skin in order to minimise irritations. The belts had electrodes for vital body functions. During communication sessions with the station, the doctors at the TsUP would receive electrocardiograms, seismo-cardiograms and pneumograms (i. e. breathing activity) in order to monitor the cardiovascular systems of the cosmonauts. In addition, there was the Polynom apparatus to monitor their physiological activity. This could measure 25 different parameters, but only five at any given moment, and it involved two men: one as the test subject and the second to make the measurements, which were recorded for later transmission to Earth. Although more sophisticated than the belts, this apparatus was used only infrequently.

The results of the biomedical tests provided important information on the general health of the three men during their exposure to weightlessness. Dobrovolskiy and Patsayev both had increased hearts rates, increased arterial pressure and an increase in the blood’s exchange rate. In contrast, the cardiovascular system of Volkov, the veteran, was more stable.

0.51 a. m.

“Good morning,’’ called Zarya.

Dobrovolskiy: “Good morning. I report that everything is all right. Yantar 2 just finished exercising on the treadmill. Yantar 3 is resting. During the period between 16.00 and 18.30, ventilation fan No. 7 was buzzing. Obviously something has been drawn into it. We opened the panel. … Just after 18.30, the buzzing ceased. Can we switch to the second ventilator?”

Zarya: “We understand. Do that. During physical exercise please do the following experiment. During the running period on the treadmill, someone should enter the descent module and look through the portholes to observe the vibration of the solar panels. Monitor the period and amplitudes of any vibrations.’’

One innovative piece of apparatus on Salyut was the ‘Veter’ (‘Wind’).[70] With the ‘penguin’ suits, it was to help the cosmonauts to overcome the long-term effects of weightlessness. The ‘waist’ was fastened to the wall by several supporting struts, and the leggings were rubberised. Once a cosmonaut had hermetically sealed his lower body into the apparatus, a pump extracted some of the air from the leggings. The function of this lower-body negative-pressure apparatus (ODNT) was to draw blood into the lower part of the body, just as if the cosmonaut were stood upright on Earth. In weightlessness the feet do not require so much blood, and therefore the cardiovascular system rapidly adapts by transferring 1.5 litres of blood to the upper body – in particular to the chest and head, which is why on their first days in space the cosmonauts felt ‘swollen headed’. Over time, most of this excess is removed by

increased urination. The cardiovascular system is greatly stressed on returning to Earth. The reduced amount of blood that is circulating in the upper part of the body drains to the feet, imposing a considerable pressure on the vessels. While in space, the cardiovascular system loses the compensatory function. The doctors call this an ‘imbalance’. When a cosmonaut stands up after returning to Earth, his weakened cardiovascular system is unable to supply blood to his head, the brain is temporarily starved and there is a risk of fainting. This is called ‘orthostatic intolerance’. The air pressure in the ODNT was reduced gradually to ‘train’ the cardiovascular system to adapt to a state approximating that of gravity on Earth. The ‘vacuum’ test had two stages: in the first stage the pressure was reduced to -27 mm of mercury for two minutes and then to -36 mm for three minutes; for a total of five minutes. At the cosmonauts’ initiative, the second stage could be extended to -70 mm. Using the ODNT involved two men, one as the subject and the other to operate the apparatus. The ‘vacuum’ condition was reported to be a pleasant sensation.[71] After each session, the test subject was required to have the parameters of his cardiovascular system measured.

03.54 a. m.

Zarya: ‘‘Yantars, today is a medical day, so do not take off your belts.’’

Dobrovolskiy: ‘‘Periodically, I will switch it on.’’

From Volkov’s diary:

10 June. Exercise on a treadmill and with a chest expander. Toilet. I brushed my teeth with real toothpaste. Again, something dropped into the ventilator. This time it was a food bag. When I removed the medical belt there were no red spots on my skin.

Viktor is sleeping in the transfer compartment. His arms are outside the sleeping bag, and float strangely in the air. Zhora is at his position – the left seat of the main control post. He has used the new cream under his medical belt.

I shaved, but not too much – I’ve decided to grow my beard.

From Patsayev’s notebook:

I continued with daily shaving. The razor is specially designed with a setting to collect the hair, but it is not close enough and the hairs fly away.

On 10 June, the cosmonauts began daily participation in TV shows. Wearing their ‘penguin’ suits, they talked about themselves, reported their activities and showed some details of their home in space. During one Cosmovision telecast,[72] Volkov said of Salyut’s dimensions: ‘‘It’s so big that it takes some time to swim from one end to the other.’’

From Patsayev’s notebook:

We had the first television broadcast. They asked the commander about our work on board the station, and all of us about our first impressions of being in space. It is nice to study geography, astronomy and physics in space with my colleagues. Virtually entire continents, seas, and islands are visible. For example, it is easy to recognise Australia, Crimea and the Mediterranean. In 90 minutes you get a trip around the world!

At 2.40 p. m. the station left the communication zone, and drew to a close the fifth day.