The drama of the Granites

INTO SPACE

After the press conference at mid-day on 20 April 1971, the Soyuz 10 cosmonauts and their backups went to Pad No. 1 to inspect the 50-metre-tall rocket, enclosed by its service structure. Also present were hundreds of engineers, technicians and the military who managed Baykonur launch operations. The tradition of this gathering had been established a decade earlier, when Gagarin had prepared to ride a similar rocket from the same pad to become the first man to orbit the Earth.

All nine cosmonauts stood in line: the prime crew at one end, then the first and second backups. Behind them were senior people from the TsKBEM, the Air Force, the Strategic Rocket Forces, the Ministry for General Machine Building and the Academy of Sciences. After being given flowers, one by one the cosmonauts were introduced to the launch team. As the spacecraft commander, Shatalov gave a brief speech to thank the launch staff and all of the institutions involved in preparing the mission.

The launch was scheduled for 5.20 a. m. local time (3.20 a. m. Moscow Time) on 22 April. Despite the overnight heavy rain, it was decided to proceed as planned. On arriving at the pad, the cosmonauts rode the elevator up the service structure, entered their craft and strapped into their couches. One by one, the service masts were swung away from the vehicle and people left the pad. The final preparations were conducted from the nearby command bunker, with the cosmonauts participating by radio. But with only a minute remaining before the rocket engines were due to ignite, the umbilical that had supplied electrical power failed to retract from the third stage, and Mishin, who was the technical director for the launch, halted the operation.

As Shatalov recalls: “We were awaiting the command: ‘The key is on the Start switch’. But instead from the command bunker we heard: ‘Prepare for evacuation! The launch is delayed for a day!’ This was nothing new for me. I’d heard the same command in preparing to launch on Soyuz 4. Then I was so disappointed, but this time I accepted it readily. I looked at Rukavishnikov – it was to be his first launch –

and saw how much he was suffering. Probably he was thinking everything was over, so I encouraged him: ‘Cheer up, everything will be all right! Tomorrow you will be launched for sure!’ Rukavishnikov did not respond. Aleksey joked with me: ‘There are always problems with you. Everyone else goes on the first attempt, except you! It is clearly the number thirteen!’ ’’ In the 10-year history of the Soviet programme, the only other time that a launch had been abandoned after the crew had entered the spacecraft was the first attempt to launch Shatalov in January 1969 – evidently he was jinxed by virtue of being the 13th cosmonaut.

The bunker ordered the cosmonauts to remain seated and await the arrival of the evacuation team. The cosmonauts understood the reason. If there were to be a false signal to the launch escape system, this emergency rocket would instantly draw the orbital and descent modules up away from the remainder of the vehicle, and if this were to happen the three men would need to be safely in their couches. Fortunately, there was no false command. As soon as the vehicle was ‘safe’ and the service structure reinstated, the evacuation team opened the hatch and helped the three men out. For the two hours that they had spent in the cabin they had been at a pleasant + 28°C, but outside it was still raining, there was a fierce wind, and the temperature was freezing, so they were given warm clothes for the bus back to the Cosmonaut Hotel.

An inspection by the technicians established that the umbilical tower to the third stage had failed to disengage because rain had accumulated in the connector and frozen it into place. The State Commission decided to retain the rocket loaded with propellant, and to reschedule the launch for the following day. The next night the temperature dropped to -25°C, and when the crew returned to the pad just after midnight they wore black leather coats over their lightweight cotton flight suits for protection against the weather. After making a brief report to General Kerimov, the cosmonauts once again entered their spacecraft.

The umbilical again refused to retract, but Mishin, knowing the reason, allowed the operation to proceed, and Soyuz 10 successfully lifted off at 2.54 a. m. Moscow Time on 23 April. As it did so, Yeliseyev called poetically: ‘‘The sky is cloudless, clear and starry, and the dawn is breaking. We’re ready to go up.’’

Soyuz 10 entered a slightly higher orbit than planned, its altitude ranging between 210 and 248 km, its plane inclined at 51.6 degrees to the equator and with a period of 89 minutes. At orbital insertion, it was 3,456 km ahead of the Salyut station. The first three revolutions of the Earth were without problems. The plan was to perform an automatic orbital manoeuvre on revolution 4, but this was not possible owing to an error in the programming logic for the command – evidently a problem involving the gyroscopic system. The mission controllers on Earth scheduled the manoeuvre for the next revolution, but the parameters could not be specified until the rate at which the initial orbit was decaying had been determined, which could not be done until the spacecraft was once again in range of the Soviet tracking radars. Once the necessary computations had been performed, the data was read up to the spacecraft, but this left insufficient time for the crew to key in the data and the opportunity for the action was missed. In addition, it seems that the ionic sensors that formed part of the spacecraft’s orientation system malfunctioned as a result of contamination of

|

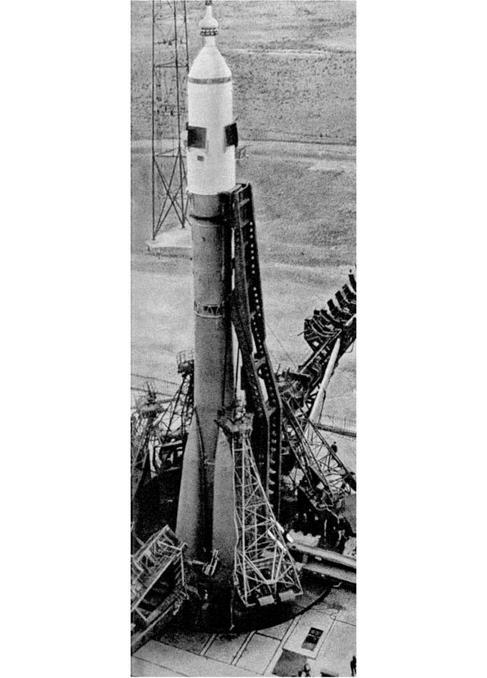

A rail transporter delivers Soyuz 10 to the pad. |

|

The rocket erected on the pad, but with the split service structure yet to be raised. |

|

The Soyuz 10 crew give a press conference at Baykonur. |

|

|

The three crews assigned to DOS-1 are introduced to the launch team at the pad: Shatalov, Rukavishnikov, Yeliseyev, Leonov, Kubasov, Kolodin, Dobrovolskiy, Volkov and Patsayev (far right).

|

Shatalov (centre) reports his crew’s readiness for the Soyuz 10 mission prior to going to the pad for launch. |

their surfaces – a common problem for spacecraft during their first hours in space, but easily rectified simply by allowing the harsh sunlight to vaporise the thin film of contaminant. Finally, Shatalov made the manoeuvre manually at 1.34 p. m., with an impulse lasting 17 seconds.

With the rendezvous initiated, the cosmonauts were free to open the internal hatch and enter the orbital module. Yeliseyev recalls: “Together with Volodya, I floated into the more spacious orbital module. We advised Nikolay to remain in his seat in the descent module for a certain time, and to move his head as little as possible. He was in space for the first time, and our desire was to help him to avoid a vestibular disturbance. Nikolay felt completely normal, but he didn’t immediately master the visual situation. I remember that when I wanted an item from the descent module, I swam in through the hatch head forward, my legs in the orbital module, and I asked Nikolay to give me the item. On hearing my voice he immediately turned his head towards me, and I saw consternation on his face. Then he said: ‘To the hell! Could you at least arise in a human manner!’ And we both laughed.’’

In accordance with established tradition, Soviet television did not show the launch until nearly 8 hours afterwards. The 45-minute black-and-white broadcast included a recorded interview with Shatalov, who said the mission would mark a new stage in the exploration of space and contribute to the establishment of space stations and long-duration flights. It then provided a view of Shatalov in the spacecraft, wearing his dark flight suit and a white communications helmet. The radio call-sign for this mission was ‘Granit’ (‘Granite’), and each man had his own numeral. The people heard mission control talking to Rukavishnikov: ‘‘Granite 3, please check your radio apparatus before attempting to speak to us again, as you are coming through garbled. Please, Granite 3, don’t speak so fast!’’

|

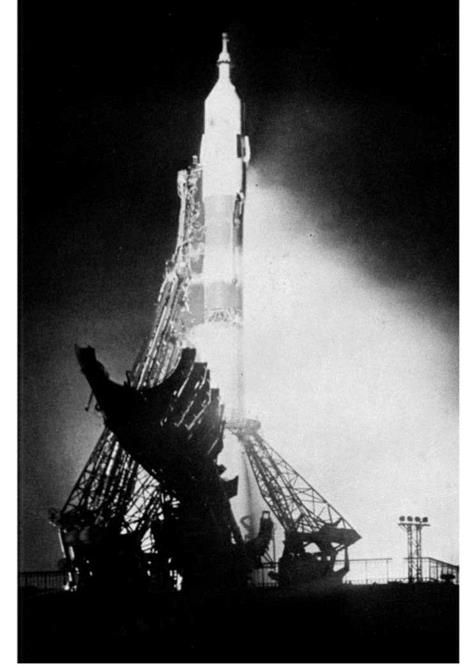

Minutes before a Soyuz launch. |

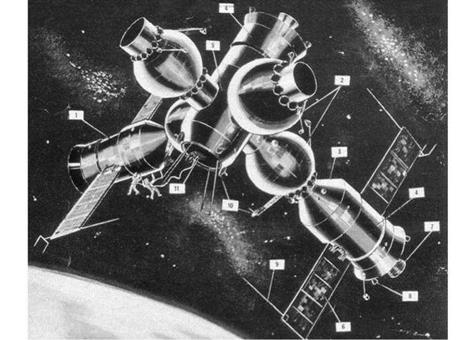

The official Soviet news agency TASS reported that the cosmonauts had started to conduct a programme of “joint experiments” with the orbital station launched four days previously. But there was no indication of the objectives of the mission, or its intended duration. No information had been released about the size of the station, or its apparatus. As far as anyone was aware, everything was going to plan. However, not only had the cover of the station’s scientific module failed to release, there were now other problems. On the second day there were indications that two fans inside the main compartment had failed, and since then others had failed. In fact, by now only two of the eight fans were available to ventilate the air in the station. Despite the absence of official information, knowledge of the capability of the Proton rocket enabled the station’s mass to be estimated at 15 tonnes, and the Daily Mail included an artist’s impression based on information from ‘Iron Curtain’ sources that showed a two-storey cylinder some 3.5 metres in diameter and 7 metres tall with a volume ten times larger than the cramped Soyuz spacecraft – which was correct.

The Soviets did not actually announce that Soyuz 10 would dock; observers in the West knew that officials would not disclose an intention until it had been achieved. As a result of recent newspaper articles by Academicians Keldysh and Petrov, there

|

In the absence of official information, Western analysts speculated that Salyut was a ‘hub’ on which departing Soyuz spacecraft would leave their orbital modules loaded with specialised apparatus. |

was a belief that the Soviet Union was following a bold plan, with Salyut as just the first step. In any case, the fact that Soyuz 10 was commanded by Shatalov was a strong hint that a docking was planned. Interestingly, some people thought that the Soyuz 4/5 mission had been a rehearsal, and Yeliseyev and Rukavishnikov would make an external transfer to the station! Some Western newspapers suggested even more implausible theories, including that there was a large centrifuge on the station to simulate Earth’s gravity. And there was speculation that Salyut was a ‘hub’ with four docking ports, and each Soyuz to visit would leave its orbital module in place in order to expand the station’s facilities.