EXPERT IN SPACE RENDEZVOUS

Vladimir Aleksandrovich Shatalov, nicknamed Volodya, was a familiar face for the journalists. When they saw him at the Congress of Communist Party in Moscow a few weeks earlier they had asked him when he was going into space again, and he had replied that he was ready to fly and would launch the next day if permitted. The journalists had laughed, not suspecting that an important event in cosmonautics was imminent. If they had known that a space station was being prepared, they certainly could not have imagined that the tall colonel with the blue eyes had been appointed to command its first crew just two months previously!

Shatalov was born on 8 December 1927 in Petropavlovsk in northern Kazakhstan. When he was two years of age his family moved to Leningrad (now St Petersburg), and there during the Second World War he served in the same brigade as his father Aleksandar, who held the Gold Star of Hero of the Soviet Union, and participated in the legendary defence of that city. In 1945 Volodya completed a special school in Voronezh for future military pilots, and 4 years later graduated from the famous Kachinsko Higher Air Force School. In September 1949 he was flying as a pilot-instructor. He married Muza Andreyevna Yonova, an agricultural engineer, and in 1952 she gave birth to their first child: son Igor. On attaining the best scores at the prestigious Red Banner Air Force Academy, Shatalov became a pilot-engineer in 1956. After a period serving as a deputy squadron commander he gained his own squadron. In 1958 their second child, daughter Yelena, was born.

In May 1960 Major Shatalov was appointed as a deputy to an air force regimental commander, and in February 1961 he became the senior instructor-inspector in the department of military readiness at the 48th Air Army in the Odessa military district. It was while there that he saw for the first time the new Su-7 aircraft. In those days the Su-7 was restricted to the very best pilots. It was an extraordinary plane, capable of flying faster and higher. In addition, it had much better ‘air combat’ performance. Since becoming a pilot, Shatalov had dreamed of flying in space. When he sat in the cockpit of the Su-7 for the first time, he thought: ‘‘I believe that a spacecraft will be similar to this one. Perhaps in the next ten years someone will make the first flight beyond the atmosphere. … Someone, but not me. I will be too old.’’ On 12 April he took the aircraft up. ‘‘As I flew the Su-7, I thought of myself as the pilot of that spacecraft. Although I did not know what it should look like, while at an altitude of 19 km I felt I was in space.’’ On landing, he heard the news that changed his life for ever: Yuriy Gagarin had just landed after orbiting the Earth in a spacecraft named Vostok. ‘‘What about me? Am I too late? Gagarin is seven years younger than me! My way to space must be closed. … Not to worry; they can conquer space without me.’’

In fact, almost all of the first 20 cosmonauts selected from the ranks of the fighter pilots were aged 25 to 35 and had very little flying experience; typically only about 300 hours in the air. But early in 1962 the Commander of the Air Army, General Kutakhov, asked Shatalov to select his best five pilots for consideration as potential cosmonauts. On reading the selection criteria, Shatalov realised that he was himself eligible to become a candidate. ‘‘The selection criteria apply to me,’’ he pointed out.

“So, what?” Kutakhov replied.

“Comrade General, I could become a cosmonaut too! May I put my name on the list?”

“Don’t be silly, Shatalov!” Kutakhov dismissed. “What do you need that for? The chance of becoming a cosmonaut is one in a thousand. You would just waste your time. After four or five years, you’ll be excluded due to your health. However, here you have a position, rank, authority, a bright future. What more would you want?’’

Nevertheless, Shatalov persisted, and was included on the list for the preliminary medical examination. He and Anatoliy Filipchenko, whom Shatalov had nominated, were selected to fly to Moscow where, with the candidates from other squadrons, they spent two weeks being subjected to various medical checks and examinations, with the number of candidates under consideration being diminished day by day. In April 1962 Shatalov successfully passed the final medical examination, then had an

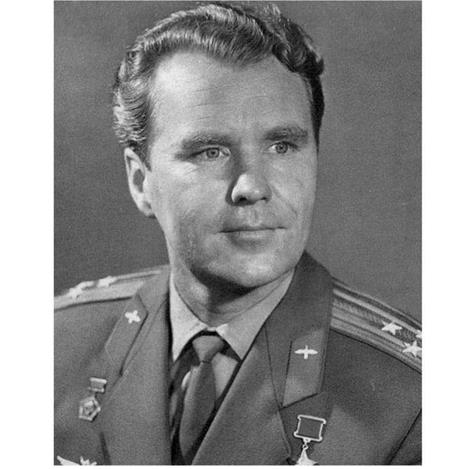

|

Colonel Vladimir Shatalov, the Soyuz 10 commander. |

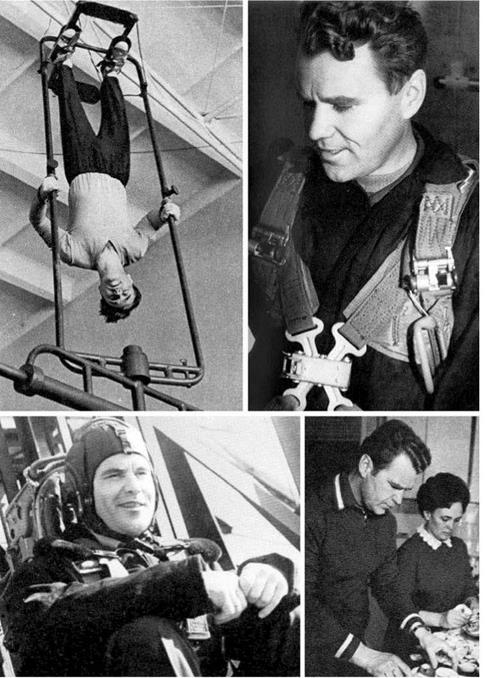

|

Shatalov in training, and with his wife Muza. |

interview with the State Commission that was responsible for cosmonaut selection, whose members included Kamanin and Gagarin. Shatalov returned to his squadron without knowing the outcome.

While Shatalov waited for news, in August 1962 two new cosmonauts – Andriyan Nikolayev and Pavel Popovich – flew a two-spacecraft mission. General Kutakhov, eager to retain Shatalov in the Air Force’s management loop, nominated him as a regiment commander. Normally this would have been excellent news, but Shatalov believed that this rank would work against his becoming a cosmonaut. What could he do? Accept the nomination? Or ask about his cosmonaut candidacy? He wrote to the Commander in Chief of the Air Force, Marshal Vershinin, and to his deputy for cosmonaut training, General Kamanin. It is not clear whether this played any role in the issue, but soon thereafter Shatalov received an invitation to travel to Moscow.

By the end of 1962 Shatalov passed the mandate commission, and on the evening of 11 January 1963 he arrived at the TsPK with 14 others as the Air Force’s second cosmonaut group. Compared to the 1960 group, the new cosmonauts were generally older, better educated, higher in rank and more experienced. All had an engineering qualification, some were test pilots, and several were non-pilots from the Strategic Rocket Forces who had served at Baykonur – the pilots referred to them as ‘rocket men’. When he became a cosmonaut, Shatalov was a Lieutenant-Colonel with more than 2,500 hours of flying experience, which was ten times greater than most of the first group. He had flown 17 types of aircraft, including the newest models such as the Yak-18, MiG-21, Su-7B, Il-14 and Tu-104, and he was also qualified to fly the Mi-4 helicopter.

In those days all the Air Force cosmonauts lived in a 3-storey building, the tallest at Zvyozdniy. On the lower floors were classrooms, a mess room and a recreation room with billiards. There, and in several small buildings scattered among the pine and beech trees, the new cosmonauts took their first steps on the road to space.

The general training at the TsPK was completed in January 1966. During this time, Shatalov had classes in the theory of space flight, studied the systems of the Vostok and Voskhod capsules, made 10 flights in aircraft that simulated weightlessness and performed over 100 parachute jumps. He also served as a communications operator for the Voskhod flights in October 1964 and March 1965. From May to December 1965 he trained as commander of the third (backup) crew, with Yuriy Artyukhin, for a Voskhod flight which was set for November 1965 but cancelled. From January to May 1966 he trained as the copilot of the second (backup) crew for the Voskhod 3 mission which was to last 16-20 days. His commander was the famous test pilot Georgiy Beregovoy, who was a late addition to the 1963 group. On the prime crew were Boris Volynov and Georgiy Shonin, both of whom were members of the 1960 group. The spacecraft passed the pre-launch tests, but there were repeated delays in mating it with the rocket, and in May the launch was cancelled – together with the remainder of that programme. If it had been launched, Voskhod 3 would have been the first manned space flight since the death of Korolev. The new Chief Designer at the TsKBEM, Mishin, with the support of the Kremlin, had decided that to continue with Voskhod would represent a diversion of resources away from the development of the much more capable Soyuz spacecraft.

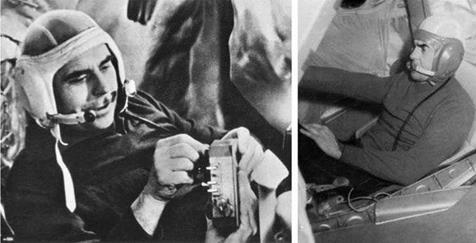

|

|

|

|

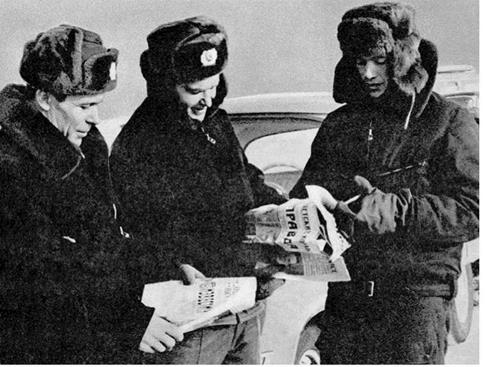

Khrunov (left), Shatalov and Yeliseyev catch up on the news after landing in the Soyuz 4 spacecraft. |

Shatalov was immediately transferred to Soyuz, and from January 1967 to January 1968 trained as commander of the third (backup) crew, with Volkov and Kolodin, for the role of a passive spacecraft on a docking mission. In the meantime, he served as a communicator for the Soyuz 1 flight that claimed Vladimir Komarov’s life. Having trained for the passive role in a docking, Shatalov was reassigned to train as commander of the third (backup) crew of the active spacecraft, and he completed this training in July 1968.

As the programme prepared to resume manned flights, from August to October Shatalov prepared for a mission that called for docking with the unmanned Soyuz 2. “Volynov, Beregovoy and I were training for this flight,’’ he recalls. “In the final exam, I had the highest score at ‘5’, Volynov had ‘4’ and Beregovoy’s score was very low. They decided to set a second examination. Volynov and I both scored ‘5’, but Beregovoy’s score was low again. After we flew to Baykonur, Beregovoy went through additional training and sat another examination; he managed to scrape a ‘4’, and was nominated to fly Soyuz 3. Behind this decision was Beregovoy’s authority as a test pilot and his long acquaintance with Kamanin. Despite his poor scores, it was thought that it would be good for morale to nominate a famous test pilot who had flown combat missions against the Nazis. Other candidates – including in the early stage Feoktistov – were excluded. Beregovoy tested the systems of the modified spacecraft, but unfortunately he failed to achieve a docking.”

Shatalov continued to train to fly the active vehicle in the rendezvous and docking of two manned spacecraft, and on 14 January 1969 was launched as commander of Soyuz 4. On 15 January Soyuz 5 lifted off with Volynov, Yeliseyev and Khrunov, and the following day Shatalov made the first docking between two manned space vehicles, and then Yeliseyev and Khrunov made an external transfer and returned to Earth with Shatalov on 17 January.

The testing of rendezvous and docking, spacewalking and the external transfer of cosmonauts from one vehicle to another was an important contribution of the Soviet lunar landing programme, as that plan called for the cosmonaut who would land on the Moon to spacewalk between the command ship and lander in lunar orbit both prior to and following the landing. As an experienced instructor test pilot and one of only a few cosmonauts able to fly a helicopter, Shatalov spent a short time after the Soyuz 4/5 mission on the N1-L3 programme. He went to the test pilot school for the Mi-8 helicopter, to use this to simulate a lunar landing. Due to the limitations of the N1 rocket, the lunar module would have very little fuel for manoeuvring to select a landing point. In fact, the cosmonaut would not see the ground until the final 30-40 seconds of the descent. Immediately after the spent propulsive stage was jettisoned, he would have to rotate the lander for a view of the surface and set down as soon as possible. The helicopter was used to rehearse this final phase of the descent. Special covers were installed on the cockpit window, and after the instructor had climbed to an altitude of 70 metres he would open the covers to give Shatalov a view of the ground, and then Shatalov took over and attempted to land in a relatively small area in the available time. Shatalov was not actually assigned to an L3 crew; his role was to assess this training.

On his next space mission in October 1969, Shatalov was not only commander of Soyuz 8 but also in charge of the three spacecraft participating in the ‘group flight’. This mission came as a surprise, as in August he and Yeliseyev had entered training as the single backup crew for the Soyuz 6 and 8 two-man crews and, with Kolodin, as the backup crew for the Soyuz 7 three-man crew. The prime crew for Soyuz 8 was Nikolayev and Sevastyanov but they failed several simulations, and therefore on 18 September, following the final examinations, the flight was reassigned to the backup crew. The three spacecraft were launched on successive days, Soyuz 8 on 13 October. Its primary objective was to rendezvous and dock with Soyuz 7. During these operations, the cosmonauts on Soyuz 6 were to fly close by and take pictures of the other two vehicles. Unfortunately, the Igla system on Soyuz 8 failed. Shatalov attempted to continue the approach manually, but without success. On landing on 18 October Shatalov admitted that he was happy at his safe return, but wished his flight could have been longer. Although the main task had not been accomplished, the Kremlin celebrated all seven cosmonauts as heroes.

In 1969 Shatalov’s former patron, General Kutakhov, had become Commander in Chief of the Soviet Air Force. He wished to assign Shatalov to succeed Kamanin, and Shatalov duly received the nomination from the Central Committee of the Communist Party to become General Director of Cosmonaut Training in the Soviet

|

Nine months after his first flight, Shatalov (left) was named to command Soyuz 8. The main objective of docking with Soyuz 7 was not achieved, and after 5 days in space with Yeliseyev (centre), they returned to the Earth (right). |

Air Force High Command. However, by late 1969 Zvyozdniy was rife with rumours of the DOS space station programme, and as the only cosmonaut to have achieved a docking in orbit Shatalov’s thoughts turned towards a third flight, this time to a space station. He wrote to Kutakhov: “What are one or two space flights for a cosmonaut? I think a cosmonaut should fly at least ten times in space. This is already a profession. I believe I would be more useful as a cosmonaut. Things are still in the early stages, so let me fly. Above all, now that the space station is developing, permit me to work on it.’’ Kutakhov agreed, but asked Shatalov to promise that after completing his third flight he would replace Kamanin. To Shatalov’s delight, in 1970 he was nominated to command the crew to fly the first space station mission. He went to Baykonur for the launch of Soyuz 9 in June 1970, and when Nikolayev and Sevastyanov were presented to the journalists the fact that Shatalov was seated beside Kamanin was an intimation of Kamanin’s imminent retirement.

When during the first reshuffle Shatalov was reassigned from the first to the third crew, he accepted that he would not have the distinction of visiting the world’s first space station, but the second. But then Shonin was dismissed and at the last minute Shatalov got his wish.