In the words of the Air Ministry:

Following the Interdependence meeting between the Heads of Government of the UK, the USA and Canada in September 1957, a Tripartite Technical Committee met in Washington in December 1957 and established a number of sub-committees to cover specified areas, one of which was strategic air to surface weapon systems. [This] subcommittee decided that an examination of the field should be undertaken by a joint RAF/USAF Task Group which met in Washington in April and November 1958.

The Task Group then issued a requirement for a missile which was circulated to industry, and a meeting was held to evaluate these proposals. To the astonishment of the British representatives present, proposals were produced from more than a hundred American companies. The meeting narrowed this down to 15 firms, who then gave brief presentations. From these, the Douglas design was then chosen.

The USAF did not want to be left out of the scramble among the US armed services for nuclear weapons systems. A system such as the new proposed missile would significantly enhance the capabilities of Strategic Air Command (SAC), although it was not envisaged so much as a strategic weapon, a ‘city buster’, but rather more as a tactical device. SAC’s long range bombers would take several hours to reach the heart of the USSR and would have to overfly a

|

Figure 52. A Vulcan bomber carrying two Skybolt missiles.

|

good deal of hostile territory. The new missile was intended to be fired as the aircraft approached Russian borders, and the relatively low yield warhead was designed to suppress Russian air defences so that the aircraft would be able to deliver their multimegaton bomb load to Russian cities. Thus it was not a major weapon in the US arsenal, which already had Atlas, Titan and Minuteman ICBMs, as well as Polaris and the bombers of SAC. Instead, it was seen by SAC as a way of enhancing its credibility, and not being elbowed out by these other systems.

The initial requirement issued in January had been for a joint USAF/RAF missile with a range of 1,000 nautical miles, a weight of 10,000 lb and a c. e.p. of

3,0 ft. The warhead would have a weight of 600 lb and a yield of 0.4 Mt or 400 kT. A report on the progress of WS-138A, dated July 1959, was prepared by Group Captain Bonser of the Air Staff after a visit to the USA. WS-138A fitted British requirements perfectly. The range was such that strikes against almost any part of the Soviet Union could be launched without having to overfly hostile territory. Each Vulcan would be able to carry two missiles comfortably. Given that the US was to pay almost all the development costs, it would be an extremely cheap deal, and it offered the possibility of extending the useful life of the V bombers by several years.

Douglas estimated the overall cost of the programme to the RAF at between £42 million to £48.5 million, exclusive of development costs of some £2.5 million. The RAE considered that the predicted c. e.p. of 5,350 ft compared favourably with the Thor missile. WS-138A looked to be a bargain. In June 1959 representatives of the V bomber firms, Avro and Handley Page, as well as officials from the Ministry of Supply, visited Douglas to give them further details of the V bomber designs.

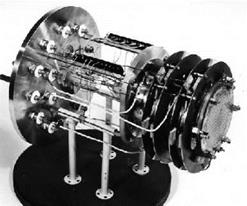

Skybolt was very different to Blue Steel or any of the other missiles carried by bombers since it was not intended to fly in the atmosphere, but was a fully ballistic missile. It had two stages, and was carried underneath the wings of the aircraft. Navigation was mainly inertial, but would include a star seeker sensor to improve accuracy (this is why it could not be carried in the bomb bay: the sensor needed a clear view of the sky). It was planned that the Vulcan would carry two missiles, one under each wing. There would be difficulties fitting the missile to the Victor (ground clearance was the issue), but the problem was not insuperable.

Thus by the time the BND(SG)13 had begun its deliberations, Skybolt was well under way. Its development costs would be paid for by the United States. It would extend the useful life of the V bombers for years to come – perhaps to 1970 or beyond. It needed little or no new infrastructure. There was just one snag – how to cancel Blue Streak in favour of Skybolt and make it look convincing.

Early drafts of the Powell report are fairly neutral in tone. As the weeks go by the tone sharpens, and the final report devotes ten or more paragraphs discussing the vulnerability of Blue Streak, with the scenarios becoming increasing convoluted. Thus:

If we assume that the Soviet attack would be made of ballistic missiles of an accuracy equal to that which we expect to achieve ourselves (0.55 NM) and that a warhead of at least 3 MT would be available, 95 per cent of the underground BLUE STREAK sites could be destroyed by between 300-400 Soviet missiles. Even allowing for the requirements of air-defence weapons for the protection of the Soviet homeland, and for the need simultaneously to pose a serious threat to the United States, we have no doubt that the Soviet stockpile by 1967 would be sufficient to provide these warheads for attack on the United Kingdom.

The crucial paragraphs read:

As ballistic missiles cannot be recalled once they had been fired, the political decision to retaliate must also have been taken before this means of evading a preemptive attack can be adopted. For this tactic to succeed, authority would need be delegated to order nuclear retaliation on radar warning alone. We do not believe that any democratic government would be prepared to delegated authority in an issue of such appalling magnitude.

This analysis shows that unless the political decision were delegated, the Soviet Union could carry out a successful pre-emptive attack on the BLUE STREAK sites, whether these were underground or on the surface; and that even if the political decision were delegated, the Soviet Union could still make a successful pre-emptive attack on the United Kingdom alone.

What of the vulnerability of the V bombers? The report has one paragraph:

Four minutes are presently required to enable the V bombers, when operating from the planned dispersal airfields, to take-off and fly clear of a nuclear attack on their bases. Given 24 hours warning the V bomber force will be able to react in time to evade a pre-emptive attack made with missiles launched on a normal trajectory. If, however, the Soviets were to fire missiles on low trajectories from East Germany, the effective time for evasive action might be as short as three minutes. The Air Ministry believe that with improved techniques it should be possible to reduce the V bombers reaction time. But, in any event, the arrival of the Soviet missiles would inevitably be spread to some extent and some of the bombers would probably be able to escape. Furthermore, for short periods during a time of tension, it will be possible to reduce this risk by maintaining a proportion of the force on standing patrol. In either event, however, the capability of the V bomber force would be greatly reduced.

Whereas Blue Streak, in its hardened silo, would apparently not survive, ‘some of the bombers would probably be able to escape’. To use a modern metaphor, this analysis does not seem to be using a level playing field. Furthermore, whilst some might be maintained on a quick reaction (four minute) alert, it will not be that many. Aircraft have to be serviced, crews have to rest. The three or four minutes mentioned is also the time from detection of the warning to the arrival of the missiles. The time between receipt of the warning from the radars and the order to scramble has not been factored in – and Bomber Command will not be keen to scramble unnecessarily. If the aircraft are scrambled, and the warning turns out to be false, the aircraft have to be turned back, landed and refuelled – taking them out of the picture until all this is done.

This analysis suited the Air Staff very well. It was, after all, the RAF who would operate Blue Streak once deployed, but the option of Skybolt now opened up a new range of possibilities. Rather than operating from a hole in the ground, the RAF would revert to its traditional role of flying aircraft. The V bombers would be given a whole new lease of life. As far as they were concerned, Skybolt was far preferable to Blue Streak.

In this context, the letter which Watkinson wrote to Sandys contains an interesting comment:

The Chiefs of Staff have been considering their attitude to Blue Streak and have now given me their unanimous advice that they find Blue Streak, as a fire first weapon, unacceptable. I am afraid Dermot sold the pass here to begin with.14

Dermot refers to Dermot Boyle, Chief of the Air Staff, and it is clear from Watkinson’s comment that Boyle was not at all reluctant to see Blue Streak go.

The Foreign Office representative (and more importantly, the Chairman of the Joint Intelligence Committee), Sir Patrick Dean, did send a note dissenting from the Study Group’s conclusions, but the Foreign Office had no great stake in the outcome – their main interest lay in the preservation of a British deterrent, which the report provided.

And not surprisingly, it was the Treasury representative that was the most vociferous in his opposition. One of the key phrases in a memo he wrote to the rest of the Study Group is: ‘… surely we would not decide to equip our troops with spear proof shields if we know that by the time we have made their shields the enemy is going to have fire arms’ – in other words, the Blue Streak silo may be adequate now, but it won’t be by the time the missile is deployed. Elsewhere in the same memo he says, ‘I think we ought to “show our working” somewhere’, which is presumably a reference to the 300-400 missiles.

As an advisor to the air staff put it:

Mr Fraser’s letter is clearly directed to killing at Blue Streak in two stages – first comes the politically more acceptable proposition that we should abandon underground deployment for Blue Streak. When this is accepted, the need to have the weapon at all can be questioned.

And so we must then try and see why the report comes to the conclusion that it does.

The oddest feature is that prior to the report, there are many estimates made by the Air Staff and the Ministry of Supply as to the survival rate of Blue Streak in a silo. To give one example, one Air Ministry memo gives the survival rate of Blue Streak when attacked by a one megaton warhead missile thus:

|

c. e.p. 0.5 nm

|

1 nm

|

2 nm

|

3 nm

|

4 nm

|

|

Above ground 0%

|

0%

|

6%

|

29%

|

50%

|

|

Below ground 50%

|

84%

|

96%

|

98%

|

99%

|

Quite how these figures were arrived at is not clear. Above ground survival rates are easy enough to estimate, but the underground figures depend on the survivability of the silo, and it is never made clear what assumptions are being made in all these various estimates. The other major factor is the c. e.p. of the missile – obviously the more accurate, the higher the ‘kill rate’. The Powell report assumes a c. e.p. of 0.55 miles, although with no apparent justification. Interestingly, the chairman of the JIC is a member of the committee: the estimate of the accuracy of Russian missiles obviously does not come from him, and, more interestingly, he writes a note subsequent to the publication of the report to say he does not agree with its conclusions.

It is clear from all these memos and estimates that the supporters of Blue Streak thought that they had an unassailable case; that underground-based Blue Streak would survive a Russian attack relatively unscathed. The first time this assumption was queried was in a rather obscure paper written for the equally obscure Air Ministry Strategic Scientific Policy Committee in October 1959. The paper is unsigned, but bears all the hallmarks of Solly Zuckerman, Chairman of the Committee, later to become Chief Scientific Adviser to the Ministry of Defence. The important section is hidden away in paragraph 17:

The vulnerability of static bases to ballistic missiles depends upon the accuracy and power of the attacking weapons. The operational reliability of any missile system also affects the number of missiles required to knock out any target given a specified accuracy. Intelligence estimates of present Russian missile accuracy and known results of USA test firings indicate that there is no technical or scientific obstacle to the achievement of an accuracy of some 2500 ft [0.42 nautical miles] for comparatively reliable 500/1500 mile range missile systems. In the case of the USSR we should expect this level of accuracy to be achieved at the latest by 1970, and possibly sooner.

He then goes on:

Given that the enemy knows through his intelligence services where our fixed installations are, and making the prudent assumptions that he can launch a surprise attack of sufficient speed and accuracy, it must be concluded that by about 1970 at latest, and possibly before, the USSR could neutralise all fixed UK static bases, whether they be airfields or above ground or below ground missile sites.15

This is true in a very limited sense. The underground sites could be destroyed if the scale of the attack is great enough. The question then comes whether the Russians could or would launch an attack on this scale. The Powell report maintained that 300-400 3MT missiles with a c. e.p. of 0.55 miles could destroy the launchers. The more important questions were whether the Russians were capable of launching such an attack, and whether they would actually do so.

Professor William Hawthorne was also a member of the same committee, but he was already a silo sceptic, as a note to CGWL, Sir Steuart Mitchell, in 1956 indicates: ‘I can imagine a few “impregnable” subterranean fortresses being built at enormous expense, but not many, since politicians may find them hard to justify.’16

The picture is further complicated by the close relationship between Zuckerman and Mountbatten. In 1959 Mountbatten became Chief of the Defence Staff, and Zuckerman was a highly influential Government scientific adviser.

Zuckerman was adept at finding his way around the ‘corridors of power’ being offered the post of Minister of Disarmament in the first Wilson administration (he refused). He was certainly heavily involved in many of the negotiations about Polaris and Skybolt with the US Government, and had very decided views on military matters and the deterrent. As well as being an active proponent of Polaris as against Blue Streak, he is supposed to have wielded considerable influence, in conjunction with Mountbatten, in the decision to cancel the TSR2 aircraft. It is interesting therefore that the first suggestion of vulnerability comes from someone associated with Mountbatten.

All these arguments would soon become academic (although objections to the report would rumble on for two or three months), since the Chiefs of Staff used the conclusions of the report as a pretext for a letter to Watkinson, the new Defence Minister:

You stated in a minute dated 5th January, 1960, that you wished to obtain a decision of the future of BLUE STREAK at the first Defence committee meeting after the return of the Prime Minister, and you asked the views of the Chiefs of Staff on the matter.

We attach no military value to BLUE STREAK, and we recommend the cancellation of its further military development for this purpose, together with the planned deployment.17

The reasoning was that if Blue Streak was vulnerable to a Soviet attack, then it would have to be regarded as a ‘fire-first’ weapon. Politically, this was completely unacceptable. Earlier in the same paper, they had said,

We need a new strategic nuclear weapon system… in about 1966, but since we regard BLUE STREAK as a ‘fire-first’ only weapon we do not consider it meets this need. We therefore recommend the cancellation its further development as a military weapon. We also recommend the cancellation of the planned deployment.

The ‘fire-first’ argument comes directly from the BND(SG) report18, which contained the fatal lines:

. authority would need be delegated to order nuclear retaliation on radar warning alone. We do not believe that any democratic government would be prepared to delegated authority in an issue of such appalling magnitude.

It can be argued that the conclusions of the Powell report were, at best, disingenuous, at worst, downright dishonest. Some immediate objections were ruled out by pointing to the terms of reference (‘Our main object has been to examine the technical and operational factors’) which said that the study should not take political factors into account. This neatly avoided one very obvious objection.

In the scenario postulated, the Soviet Union would launch a surprise attack on the UK using 300 to 400 missiles, each armed with 3 megaton warheads and having an accuracy of 0.55 miles c. e.p. This attack would be sufficient to destroy the Blue Streak silos with the missiles inside, and thus the UK would not be able to launch a counter-attack – in other words, we would not be able to deter the Soviet Union from launching such an attack. The Soviet Union could thus attack the UK unscathed.

But could anyone on the study group have justified a scenario whereby the Soviet Union launched an attack of 1,200 megatons, or 1.2 gigatons(!), on the UK whilst America stood by and watched? That America would allow its troops and servicemen stationed in the UK to be annihilated? That the launch of 400 Soviet missiles, even if it later became clear that they were not aimed at America, could occur without the American authorities launching at least some missiles in retaliation? It could also be argued (as some in the Ministry of Aviation later tried) that such an attack would also be a self-inflicted wound for the Soviet Union – the fallout generated from such an attack (made all the worse by the explosions being ground bursts), coupled with the prevailing westerly winds, would render Europe and most of European Russia completely uninhabitable.

There is also a further assumption, which is that all 400 missiles are serviceable, ready to fire, and are launched (and arrive!) successfully. If 400 warheads are needed to take out Blue Streak, how many missiles would Russia have to fire in order to achieve this? What sort of ‘safety factor’ would be needed to ensure that 400 arrived on target?

It was all very well to say that such considerations were not within the terms of reference if the scenario postulated is clearly absurd, and it is certainly arguable that a scenario whereby the Soviet Union launches more than 400 missiles at the UK without American retaliation (and thus a global war) is absurd. There is the further point that 400 missiles would represent a very considerable portion of the Soviet arsenal. Would they be prepared to devote such a proportion merely to take out the deterrent of what was, in Cold War terms, such a minor opponent? Indeed, taking the serviceability point, nearer 600 missiles would be needed. Sir Patrick Dean, as Chairman of JIC should have been able to give an estimate of the number of Soviet missiles based in Europe, and the answer would probably have been nowhere near the number assumed in the report.

It would also be extremely difficult to invent any plausible political situation whereby the Soviet Union would launch such an attack on the UK in absence of an attack on itself. Britain would never launch first, since they knew all too well how vulnerable the UK would be to any nuclear attack, let alone one on this scale, and the Russians would know that too. A British attack would be, in the jargon, a ‘second strike’, which was the point of the silos being able to survive the initial strike. But what political situation could see the Soviet Union launching 400 missiles at the UK and the UK alone? Such a scenario would also have to assume that the attack would be launched in the sure and certain knowledge that America would not become involved.

Moreover, the report stated that:

The current Joint Intelligence Committee assessment is that we should get strategic warning of at least 24 hours before any heavy Soviet attack on this country. There is therefore no need to maintain our deterrent forces constantly at maximum readiness in order to guard against a “bolt from the blue” attack. But even if there is a period of rising international tension before the outbreak of hostilities, there is still a possibility that the enemy will attempt to achieve tactical surprise in the timing of his attack. The longer the period of such tension the greater the scope for tactical surprise, because deterrent forces cannot be maintained indefinitely at maximum readiness.19

So there is no surprise attack, no ‘bolt from the blue’, but, on the other hand, the Russians were supposed to be capable of co-ordinating the launch of several hundred missiles all within half an hour of each other without anyone noticing.

But what of the ‘technical’ factors? These too can be challenged, and indeed they were. 1.2 gigatons of nuclear explosion almost certainly would have taken out the Blue Streak silos, but there were a considerable number of caveats to this scenario too.

Firstly, we will assume the attack happens during what was called, rather euphemistically, a ‘period of tension’. During such a time, it is probable that some of the missiles would be fuelled and ready to launch. Because of the restrictions involving liquid oxygen, this would not be very many. The probability would be that the missiles would be rotated: after so many hours, the missiles that were fuelled up would be stood down and other missiles made ready in their place. Even those missiles armed, fuelled with kerosene, but not liquid oxygen, could be launched within about 15 minutes at the very most.

In order to ensure that all the Blue Streak silos were destroyed before any missiles could be launched, the attack would have to be very carefully coordinated, such that all the attacking missiles arrived within a very short space of time, of the order of 15 minutes. There are problems to this.

The first is that the attacking missiles will be launched from a variety of launch sites, and will have a different time of flight. Thus their launch times would have to be very carefully co-ordinated. There is also the problem that around six or so missiles would be allocated to each silo. This brings the problem of ‘fratricide’, when another warhead in the vicinity of a 3 megaton blast might well be destroyed. Further, once the first explosion has taken place, there will be a very considerable disturbance of the atmosphere, to put it mildly! An incoming warhead that meets the shockwave from such a blast would be thrown off course, so to speak. The chance of it still arriving at its aiming point is remote. Yet if the attack is staggered to allow for this, then it does give windows of opportunity, small though they may be, for a Blue Streak launch to occur. The whole point of making such an attack is to ensure that no retaliation is possible.

But let us assume that the scenario is technically possible, that such an attack is possible, and that it would take out all the silos. What of the alternative possibility: the V bombers armed with Skybolt?

There was no intention, at this stage, that the RAF would mount standing patrols in the same way that SAC did. The best Bomber Command would have to offer would be aircraft on Quick Response Alert (QRA). These aircraft could be scrambled very quickly when the order was given. Unless the crew was strapped in, with the engines running (which was a possibility, although such a state could not be maintained for long), it would take some minutes before the crew could get into the aircraft, start the engines, taxi to the runway, take off and get clear of the airfield.

There were half a dozen V bomber bases, all in eastern England. During ‘periods of tension’, the aircraft could be dispersed to alternative airfields – up to 24 were planned. The facilities at some of these dispersal airfields were not entirely adequate, and such a dispersal could not be maintained for any period of time due to the lack of maintenance facilities. Even so, with 300-400 missiles at their disposal, the Soviet Union could launch a dozen or so at each airfield, and, QRA or not, the chances of an aircraft surviving such an attack, even in the air, is remote.

Sixty Blue Streak silos or sixty bombers on airfields? Which would stand the greater chance of survival? In the face of an attack on such a scale, the probable answer is that neither would survive, and in the event of an attack on a lesser scale, I would put my money on the silos.

There is also a rather more subtle psychological point in favour of aircraft rather than missiles, which usually gets oblique mentions in such discussions, but which did appear to loom large in minds of officials and politicians. The launch of a missile is irrevocable. Once the button has been pressed, there is no way of recalling the missile or even of destroying it in flight. Aircraft, on the other hand, give something of what might called a ‘time cushion’ – they can be sent on their way, but it will still be a matter of some hours before the pilot finally presses his button to launch his missile. This reduces the chance of ‘launch by mistake’ – in other words, it might appear that the UK has been attacked, and so it is imperative to react. Suppose the button is pressed – and the report of the attack turns out to be false. If you have pressed the button in a missile silo, you have started a nuclear war. If you have scrambled aircraft, they can be recalled. This would explain a good deal of the Whitehall dislike of Blue Streak. When Polaris took over from the bombers, there was still that time cushion. There was not the same sense of urgency to get in your response before your deterrent was destroyed.

But to return to the Powell report: once circulated, it drew one of two responses, depending which side a person was on, and by this time, there were few who were neutral. If someone was against Blue Streak, then the report was read and used as conclusive evidence that Blue Streak should be cancelled. So many eminent people can hardly be wrong. Someone in favour of Blue Streak faced an uphill task in trying to defend the missile. Even though the conclusions might be absurd, the reputation of the project had been tarnished – perhaps irrevocably so. (Another way of telling which side someone was on was whether they referred to ‘fixed sites’ (against) as opposed to ‘underground launchers’ (in favour)!)

Sir Steuart Mitchell’s response is typical of many of the incredulous memos which came from the Ministry of Aviation:

The vulnerability of underground Blue Streak is, in my view, grossly overstated in the report. As a result, Blue Streak is presented to Ministers as exclusively a fire first weapon, with all the serious disadvantages thereof. This, in my view, is based on misunderstanding of the technical facts.

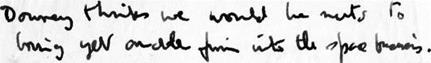

The report, in my view, accepts much too light heartedly the technical concepts of the WS.138A weapon system. History is strewn with weapon system concepts in which USAF expressed total confidence and which they pursued with great ardour for a year or two and then totally dropped. WS.138A today is where Hustler was four years ago except that the confidence and enthusiasm in WS.138A today is less than in Hustler four years ago. Hustler today is dead. To any technician familiar with the problems of a ballistic missile fired off a fixed site, the thought of putting our deterrent shirt on an American plan to fire such things off an aeroplane and having them in Service operations in the UK by 1966 or soon after as stated in the report is alarming. In my view the plan proposed in the report is dangerously unsound.20

‘Seriously unsound’, ‘grossly overstated’, ‘alarming’, ‘dangerously unsound’ – these are strong words indeed in this context, not phrases in common use in Whitehall. These are from the Government’s chief expert on guided weapons! And he goes on in a further memo to say:

To provide… 375 sites and missiles, together with roads, services, centralised communications; to give training and firing drill to crews; and to bring the whole edifice to such a pitch that they can fire the whole lot within a few seconds of the correct moment is, by any yardstick, a gigantic undertaking. It amounts in fact to an effort about six times bigger than the Blue Streak effort which it is trying to preempt. This aspect is dismissed in the report as simply being ‘within the Russian capability’ …

All these factors, in our view, added to such a gigantic total that while by itself it may be technically feasible yet it is not a practical probability. We think that the very size of this pre-emptive effort is so big as to constitute a deterrent in its own right – providing Blue Streak is deployed underground.

All this is virtually ignored in the report. .

If our politicians are at all competent, it is difficult to conceive of a war with Russia involving the UK but not also involving the USA.

If however such a situation came about, e. g. Middle East oil, it is most unlikely that Russia would pre-empt our Blue Streaks. She would surely fight such a war with conventional weapons (and win it easily this way), knowing that we know that if we “fired first” with Blue Streaks resultant Russian retaliation would destroy the UK.

Pre-empting Blue Streak in such a war is probably the last thing the Russians would do because if he did it would leave himself open to a ‘fire first’ blow of shattering size from the US.21

And then with regard to the arguments about the relative vulnerability of the V bombers and Blue Streak, Sir Steuart wrote yet another memo:

Blue Streak is condemned because of alleged inability to withstand 300 3MT rockets directed against 60 sites. It is therefore fair to consider what 300 3MT bursts could do to our V bomber force.

The Air Ministry claim that they can get “4 bombers airborne from an airfield in 4 minutes”, – presumably four minutes from the local order to scramble.

The distance travelled by a typical V bomber from the point of take-off (i. e. from point where airborne) is

After 1 minute airborne flight. 6 n. miles.

After 2 minute airborne flight. 13 n. miles.

After 3 minute airborne flight. 20 n. miles.

The disabling radius of a 3 MT airburst against a V bomber is approximately as follows:

V bomber on ground… 14-15 miles (not tethered since it is about to take off)

V bomber airborne between zero height and 12,000 ft… 12 miles

One 3 MT burst over the airfield… would therefore disable not only all aircraft still on the airfield but also all airborne bombers within 12 miles of the burst.

Further, it would be reasonable to suppose that the Russians, in addition to the airburst directly over the airfield would at the same time lay on two additional airbursts along the direction of the bomber flight path.

It will be seen that the combination of one airburst over the airfield and two airbursts about 14 miles away and about 30° to the axis of the runway would disable not only all aircraft still on the runway but also all aircraft that had become airborne during the preceding 3 minutes. If these rocket bursts occurred at any time within the period up to 6 (not just 4) minutes before the order to scramble, it is difficult to see how any significant number of the bombers could escape.

I do not know the number of airfields which the V bomber force would use under dispersal conditions, but if one supposes the number to be, say, 50 at the most, then to carry out the attack outlined above would require a total of 3 x 50 = 150 missiles.

If the Russians were in any doubt as to the direction of take-off of the 7 bombers, they could remove the ambiguity by placing two other airbursts 14 miles at 300 from the other end of the runway to cover the reverse direction of take-off. Thus, for 50 airfields, would require a further 100 missiles, thus bringing the total missiles up to 250, which is still below the 300 postulated for the knocking out of Blue Streak.

Further, a number of the dispersal airfields are understood to be sufficiently near each other for the damage radius of a burst on one airfield to overlap on to the neighbouring airfield, thus reducing the weight of attack required.

Finally, it should be realised that the bomber bases in East Anglia would only get 2‘/г-3 (not 4 minutes as commonly stated) warning by BMEWS of the Russian 1000 mile rocket if fired on a low trajectory from satellite territory.

[BMEWS: Ballistic Missile Early Warning System. There was a station at Fylingdales on the North Yorks Moors.]

This was just one of many objections – and this from the Government’s principal expert on missiles. Sandys was writing similar memos as late as March.

So, if the report was so obviously flawed, why was it put forward, and why was it accepted so uncritically? One reason was that the answer it gave was the answer that a lot of people wanted. Never mind the argument, look at the conclusion. Another reason was that the Study Group had been composed of some very eminent men, and there was the obvious appeal to authority – a group as eminent as this could hardly be wrong.

But in one sense the argument had already been lost. Blue Streak had had sufficient doubt cast upon it that revival became impossible. (Similarly, later, when the US Secretary of Defense Macnamara cancelled WS.138A/Skybolt, but still offered it to Britain, Macmillan rejected the offer on the grounds that ‘the lady’s virtue has been impugned’. The same was happening to Blue Streak.)

Indeed, the battle went outside Whitehall with the publication of an article in the Daily Mail on 4 February 1960. The headline ran ‘Blue Streak is a damp squib’ and went on:

This is the key problem – one of the most critical defence questions this country has faced – that Mr. Harold Watkinson, a senior cabinet minister, was put into the Ministry of Defence last October to solve…

His brief from the P. M. was short and to the point. First, Britain must continue trying by all means within financial reason to remain an effective nuclear power.

Second, an attempt to do this by striking a new balance between the runaway costs of the deterrent and our obvious weakness in conventional forces.

With this in mind, it follows inevitably that the first file called for by Mr. Watkinson in the Ministry of Defence was labelled ‘Blue Streak’.

In the days of his predecessor, Mr. Duncan Sandys, this file was the sacred cow. Mr. Sandys had made up his mind unalterably that Blue Streak, secure in its underground cells, was the answer for Britain.

It is said that throughout last summer Mr. Sandys faced increasing pressure from financial and military experts to think again. Apparently, he was obdurate. Only in his successor has a ready listener been found.

The most disturbing aspect of the cost of Blue Streak was strengthening military opinion that this fabulously expensive weapon would be secure underground only for a few years at most.

Once the Russians could guarantee the accuracy of their rockets within half a mile, Blue Streak would be as vulnerable as today’s Thors which stand plain for all to see fixed on their surface-launching pads in East Anglia…

The most interesting feature of this article is: where did the journalist get his information? To be as well informed as this suggests a leak from someone close to the top – although there is nothing new in that. And, further, although Blue Streak is portrayed as obsolete, no alternative is mentioned.

Other newspapers also picked up on the political implications of the struggle: another article mentioned the constant redrafting of the Defence White paper, and noted of Sandys that if he wins this Cabinet battle his personal standing among Ministers will be immensely enhanced. If he loses, his resignation cannot be ruled out.’

But despite all the arguments between Ministries and their civil servants, as we have seen, the Chiefs of Staff short-circuited the whole debate in their letter to Watkinson saying that they attached no military value to Blue Streak as a weapon, and recommending its cancellation. This was to put Watkinson in a very difficult position. He had only been Minister for Defence since the October 1959 election, and in his first Cabinet post (he would disappear from the Cabinet in the reshuffle known as ‘the night of the long knives’ in July 1962). Irrespective of all the papers from the Ministry of Aviation, and from Sandys, a Cabinet colleague who had been in successive Conservative cabinets since Churchill’s election victory of 1951, and who had been the originator of the project, Watkinson had now received a memo from the Chiefs of Staff to say they had no confidence in the weapon. There was little he could then do. If his Chiefs of Staff told him that they attached no military value to a project then Watkinson was in no position to argue. He wrote to Sandys on 9 February and, unusually, the word ‘personal’ is handwritten at the top. The letter reads:

during launch. Although effective insulation is

during launch. Although effective insulation is

was the value being considered. This is quite an elegant solution, dispensing with the weight and complexity of a turbopump, yet avoiding the weight penalties of thicker tank walls and heavy gas bottles. The only drawback is that with the relatively low thrust, the burn time will be quite prolonged, which means carrying the unburned fuel up the Earth’s gravitational potential well as the vehicle gains in height.

was the value being considered. This is quite an elegant solution, dispensing with the weight and complexity of a turbopump, yet avoiding the weight penalties of thicker tank walls and heavy gas bottles. The only drawback is that with the relatively low thrust, the burn time will be quite prolonged, which means carrying the unburned fuel up the Earth’s gravitational potential well as the vehicle gains in height. To power such low thrust chambers with a pump was impractical. Pressurising the tanks usually meant carrying large and heavy gas bottles. Instead, the proposal was to use a heat exchanger to produce ‘hot’ (relative in this context) hydrogen gas. The gas could then be used to pressurise the tanks (a further heat exchanger would be needed for the liquid oxygen tank).

To power such low thrust chambers with a pump was impractical. Pressurising the tanks usually meant carrying large and heavy gas bottles. Instead, the proposal was to use a heat exchanger to produce ‘hot’ (relative in this context) hydrogen gas. The gas could then be used to pressurise the tanks (a further heat exchanger would be needed for the liquid oxygen tank).

lb approximately

lb approximately

Interestingly, at that time ELDO was also considering the augmentation of the payload capability of its launch vehicle by the same means.

Interestingly, at that time ELDO was also considering the augmentation of the payload capability of its launch vehicle by the same means.