The Cancellation

Governments tend to make the announcements of the cancellation of a project as brief as possible. The Opposition and the Press will not follow up the cancellation of a project such as Black Arrow unless there is the whiff of a scandal. The Press was not interested; and in this case there was very little that the Opposition could use to attack the Government.

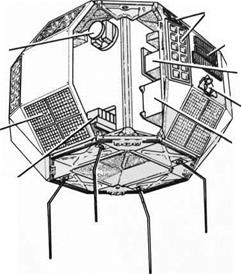

EXPERIMENTAL SURFACE FINISHES

![]()

![]()

![]()

EXPERIMENTAL SOLAR CELLS

EXPERIMENTAL SOLAR CELLS

POWER SYSTEM ELECTRONICS

ASPECT SENSORS

BATTERY

One group of people that is rarely informed of the true reasons for the cancellation are those who work on the projects, and whose livelihood depends on them. Not surprisingly, urban legends or conspiracy theories begin to emerge. The cancellation of Black Arrow was no exception.

Engineers are usually conservative by nature, and often Conservative by political inclination. One of the ‘bogey men’ of the time was Tony Benn (known earlier in his career as Anthony Wedgwood Benn, but who had now adopted a more demotic name), and to those who worked on the project, part of the mythology was that it was cancelled by Benn and the socialists, when it was actually cancelled by a Tory Government!

In reality, virtually all the opposition came from the Treasury, as the following memo from February 1969 illustrates:

I have no doubt that the Cabinet will give overwhelming approval to the Ministry of Technology’s [Tony Benn] proposals for Black Arrow. At the S. T. meeting on Friday, 21st February, all Ministers from all Departments except the Treasury were not only in favour of the proposals, but emphatically so. The reservations of D. E.A. officials [Department of Economic Affairs] are not apparently shared by D. E.A. Ministers, including Peter Shore. The least enthusiasm was shown by Sir Solly [Zuckerman, Chief Scientific Adviser to the Government], but he gave qualified support and clearly did not brief the Lord President to oppose.

2. I should in fairness add that Tony Benn put his case very attractively. It clearly has some merit and while I suspect there may be a considerable degree of optimism influencing the supporters of Black Arrow, I doubt if the Treasury arguments however skilfully deployed, will sway other Cabinet members.

3. In the circumstances I would suggest that a last ditch fight by the Treasury against Black Arrow in Cabinet could be mistaken. It might undermine the Treasury’s general position on more hopeful causes. I feel a tactically more rewarding line would be for you and the Chief Secretary to say that having looked at the proposals you feel that there is merit in them (including the proposal for a British launcher) and that you do not propose to object.20

The Ministry of Aviation had been subsumed into the Ministry of Technology in February 1967. It was further reorganised with the advent of the Conservative Government lead by Edward Heath in 1970, becoming part of the new Department of Trade and Industry (DTI). But after all the attacks on Black Arrow by the Treasury, it was actually the Aviation department of the Ministry of Technology which began the process by which Black Arrow would be cancelled. The memo in question is undated, but seems to have been written around October 1970:

As I mentioned the other day, I feel there might be considerable advantage in arranging an impartial examination of the National Space Technology Programme in the light of the recent Black Arrow launch failure [the R2 launch].

It is of the utmost importance that the next firing of Black Arrow, currently scheduled for May 1971, should be successful. We, RAE and Industry are already engaged in analysing the technical causes of the failure, but we have to recognise that there are also wider implications. Another failure, and our national technological competence as well as the future of the National Space Technology Programme would be in question. Examination of the programme as a whole by an outsider of suitable qualifications could be useful in ensuring that it develops from this point on in the best possible way.

The examination would have to take as a starting point an acceptance of our primary objective in space, which is to attain the capability in satellite technology enabling us to offer space hardware, internationally and on an industrial scale. The investigation should in addition not question the broad institutional framework of the Programme-in other words it would be accepted that the effort was a joint Government and Industry one. Within these constraints, however, the investigation should be given the widest possible remit to examine the means we have employed to reach our objective.

The formal terms of reference might be on the following lines:-

To assess the relevance and appropriateness of the Programme, in its present form, to the goal of establishing a significant national competence in satellite technology.

To study in particular the role of the national launcher (Black Arrow) in the programme; the level of effort needed to develop it into a dependable vehicle; and the cost of alternatives to it.

To report on the management of the Programme, with special reference to the launcher element.

And to make recommendations.

I believe that an examination along these lines could be of a very real help to us, especially in providing the answer to two questions — is the level of spend on the Black Arrow launcher programme a sensible one, or ought it to be increased very substantially in order to achieve real gains; and, whatever the level of sensible expenditure on a national launcher programme might be, would it be preferable and more economic to use an American launcher?

The difficulty, of course, is to find a man of sufficient managerial and technical qualification within the UK who was not already involved in the space programme. We are already separately engaged in the discussion of suitable names. My present purpose is therefore to seek your approval of the terms of reference set out above, on the basis of which we might approach a suitable candidate.21

The question was who among what have been termed as ‘the great and the good’ would be willing and available, although one stumbling block was the requirement for some technical knowledge. In the event, an impeccably qualified candidate was identified and, on 1 October 1970, accepted the invitation to undertake the inquiry: William Penney.

William Penney is best known for his work on Britain’s atomic weapons, although he had many other scientific accomplishments to his name. He won a scholarship to study at the University of London, winning the Governor’s Prize for Mathematics and graduating with First Class Honours in 1929. In 1944 he joined the British mission to Los Alamos, working on the use of the atomic bomb and its effects. On his return to England, he was put in charge of the British atomic bomb project, and saw the project through to the test of the first bomb in 1952. At this point Penney was offered a Chair at the University of Oxford. Always more inclined toward the academic life, he was keen to accept this post, but he was persuaded that the ‘national interest’ required him to continue as director of the AWRE at Aldermaston until 1959. From 1954 Penney served on the Board of the Atomic Energy Authority, becoming Chairman in 1964. He retired as Chairman in 1967, and then became Rector of Imperial College.

Given these achievements, it was unlikely that his findings would be disputed, and given his expertise in running demanding experimental programmes, he would have seemed to be the ideal man for the job. Being retired from any form of Government research meant he had no axe to grind, and would be widely seen as an impartial observer.

A briefing note for the Minister after Penney had submitted his report noted that:

Lord Penney’s approach to his inquiry was informal. By meeting the people in industry and government concerned with Black Arrow, and discussing the project with them, he aimed to make personal assessment of the management of the programme at the same time as briefing himself on the details of the project. He made two visits to industry, to see the major Black Arrow contractors – British Hovercraft Corporation on the Isle of Wight, and Rolls-Royce at Ansty, Coventry. He visited RAE Farnborough on two occasions, and had a number of discussions with the staff of space division and other headquarters divisions with an interest in Black Arrow. For details of the alternative launchers to Black Arrow he relied on information supplied by the department: he made no visits abroad in the course of the inquiry.

As might be expected, the report was thorough and comprehensive, stretching to 24 pages and 68 sections. He fulfilled his brief admirably, looking at Black Arrow and its alternatives, then considering the viability of Black Arrow within the larger framework of British space policy. His conclusions and recommendations are worth quoting:

My conclusions are as follows:

The disappointing performance of Black Arrow launcher R2 in September 1970 was not due to poor project management, bad fundamental design, or low grade effort. We know we were taking a gamble in trying to make do with so few test launches, and the gamble went against us.

The cost of launching of the X3 satellite on the R3 vehicle is almost fully incurred, and the best policy would therefore be to launch X3 in July 1971 as planned. But in spite of all the work being done to follow up the R2 failure, we cannot be sure that the gamble will not go against us again on R3. The Ministry has neither the time nor the resources to build up greater confidence in Black Arrow before X3 is ready for launch.

It is probable that with the present launch rate of one Black Arrow a year, we will still not be fully confident of its reliability by 1974 when we are planning to launch X4, the second major technological satellite. Even if the Ministry agreed to fund an increase in the launch rate, only one or two extra Black Arrows could be built and launched by 1974.

There is a three-year gap between X3 and X4, but Black Arrows are being built at the rate of one a year. This mismatch between the production rates of launchers and worthwhile satellites may well continue beyond X4, and cannot easily be remedied by adjustments to the launcher programme which is already running at about the minimum level for efficiency…

The current programme gives us too few Black Arrows to establish the vehicle as a proven launcher in a reasonable timescale, and too many to meet our requirements for satellite launches. It is therefore not a viable programme at present, and there is no easy way out of the dilemma.

And on the subject of alternative launchers, he notes:

Black Arrow has no alternative use, and the nation would have much to gain and little to lose if it were cancelled in favour of American launchers. We would be abandoning a certain political independence and a guarantee of commercial security payments, but on these two points satisfactory safeguards should be available from the US authorities.

Unless a formal approach is made quickly to the inhabitants on the availability of Scouts and other launchers for our technological satellite programme, further commitments will have to be made on Black Arrow vehicles as an insurance move.

As soon as we are satisfied that we can get the launchers we need from the Americans on acceptable terms, the Black Arrow programme be brought to a close as soon as possible. However, the launching of X3 on the R3 vehicle should proceed, and there may be a need for a further launch if problems arise with X3/R3.

I therefore recommend that:

The Ministry should make a formal approach to the US authorities as soon as possible about the availability of launchers for X4 and subsequent satellites in the National Space Technology Programme, and terms on which they can be provided.

Commitments on R5 and subsequent Black Arrow vehicles should be kept the minimum possible level while the Americans are being approached, and all work on them should be stopped as soon as satisfactory arrangements have been made for the supply of US launchers.

The X3 satellite should be launched as planned on the R3 Black Arrow vehicle in July 1971; the R4 vehicle should be completed in all major respects and used as a reserve for R3 up to the launch.

If X3 goes into orbit successfully and functions as planned, the Black Arrow launcher programme should be brought to a close without further launches.

If X3 fails to go into orbit successfully or fails to work in orbit, the Ministry will have to decide whether to bring the launcher programme to a close at that point or repeat the X3 experiments by launching the X3R on the R4 vehicle. Unless they are sure that the R4 vehicle has a better chance of success than the R3, and it is worth spending кШ million to repeat the satellite experiment, a further launch should not be sanctioned.

The X4 satellite should be launched on Scout; and Scout or Thor Deltas should be bought as necessary for later satellites in the series.

The Ministry should determine at a high level the views of British industry on the value of a technological satellite programme. If no such value can be identified the programme should be brought to a stop. If it is established that the programme is worthwhile, a plan should be drawn up for a series of future satellites so organised as to give the maximum benefit to British firms in their attempts to win contracts in the international market.22

It is difficult to argue with his conclusions, or, indeed, with his recommendations. As he correctly points out, there was a ‘mismatch between the

production rates of launchers and worthwhile satellites’. Making fewer launchers was not economic; there were not the resources to make more satellites.

The report was submitted to the Minister in January 1971, and made its way up the government hierarchy, culminating in a meeting held in the Prime Minister’s room at the House of Commons at 5:15 pm on Monday 6th July, 1971.

Those present were the Prime Minister (Edward Heath), the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (Geoffrey Rippon), the Lord Privy Seal (Earl Jellicoe), the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry (John Davies), the Minister for Aerospace (Frederick Corfield), the Chief Secretary to the Treasury (Maurice Macmillan), and Sir Alan Cottrell, Chief Scientific Adviser. An excerpt from the minutes of the meeting reads:

The Lord Privy Seal recalled that on 24 May the Ministerial Committee on Science and Technology had approved the proposals by the Minister of Aerospace that the Black Arrow programme should be stopped, that we should support the full development of the X4 satellite and that for the launching of small satellites we should in the future rely on the American Scout launcher. The Prime Minister had been doubtful about the impact of this decision on future European collaboration in science and technology, particularly as the French were developing their own launcher the Diamant. Since then however the political difficulties have largely dissolved. The Diamant programme had now been deferred and the French were themselves using the Scout launcher this year.

The Prime Minister and the other Ministers present agreed that the proposals originally approved by the Science and Technology Committee in May should now be implemented. The Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster said he did not think that the cancellation of Black Arrow would be deemed inconsistent with anything the government had said when in opposition; there had been no commitment to back any project which was not successful.

The Minister for Aerospace said he thought that the announcement of the decision would not cause great surprise and could be done by an Answer to an arranged Written Question.

The Prime Minister agreed to this and suggested that the announcement should be as late as possible.23

Three weeks later, the following exchange appears in Hansard for 29 July 1970:

National Space Technology Programme

Mr. Onslow asked the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry what progress has been made with the review of the National Space Technology Programme; and if he will make a statement about the future of the Black Arrow Launcher.

Mr. Corfield: The first phase in the review of the National Space Technology Programme has now been completed. Plans to launch the X3 satellite on a Black Arrow vehicle later this year have been confirmed, but it has been decided that the

Black Arrow launcher programme will be terminated once that launch has taken place.

We have come to this decision on Black Arrow mainly because the maintenance of a national programme for launchers of a comparatively limited capability both unduly limits the scope of the National Space Technology Programme and absorbs a disproportionate share of the resources available for that programme.

We hope to complete our review in the early months of 1972. Meanwhile work is continuing in industry on research into basic satellite technology and on the development of the X4 satellite. X4 is planned to be launched in 1974 on a Scout vehicle to be purchased from N. A.S. A.

The curious (or perhaps not so curious) feature of the announcement is how little attention it received. True, Black Arrow always had had a low profile, but neither in Parliament nor in the press was there any great comment. Perhaps the last word should be given to the New Scientist magazine, which had this to say in August 1971:

Despite considerable success with small launchers – notably Skylark – the modern sport of rocketry evidently rouses little excitement in British hearts. The now- promised demise of the Black Arrow programme, the erstwhile Black Knight venture, is unfortunate only because its death throes have been so prolonged. Announcing last week that, after a final launching later this year when it hopefully will put the X 3 satellite into orbit, Mr Frederick Corfield, Minister for Aerospace, said that henceforth Britain’s need to pursue experiments in space technology would be met with US launch vehicles. The reason essentially is that nearly all foreseeable space applications are going to require satellites in high geostationary orbits; Black Arrow falls far short of this requirement, being able to lift some 260 lb only into a near-Earth orbit.