Black Arrow Improvements

Inevitably, there were a variety of improvements suggested for Black Arrow24,25, some more realistic than others. As mentioned in the chapter on rocket motors, BSE carried out a programme to produce an improved HTP motor. The chamber that was test fired was both lighter and more efficient than the Gamma chamber used in Black Arrow, and had a higher thrust rating. This inevitably gave rise to the proposition that if the vehicle were fitted with the new chambers, then the tanks could be extended, improving performance.

|

|

The BSE report which detailed the ‘Larch’ programme suggested the following changes:

|

Total weight: |

31,095 lb |

37,514 lb |

|

Propellant load: |

28,735 lb |

35,205 lb |

|

Approx stage length: |

22% ft |

24% ft |

|

(plus interstage) |

||

|

Second stage: |

||

|

Total weight: |

7,798 lb |

10,221 lb |

|

Propellant load: |

6,618 lb |

9,063 lb |

|

Approx stage length: |

9% ft |

11% ft |

|

Third stage: |

||

|

Total weight: |

1,107 lb |

975lb |

|

Payload to 300n. m. polar orbit |

232 lb |

375 lb |

The proposal seems to have reduced the weight of the third stage: quite how is not obvious. It is easy enough to vary the amount of propellant in a liquid fuel stage, but to do so in a solid fuel stage would need some considerable redesign.

The payload increase is more than 50%, so this does seem to be a worthwhile improvement. This particular programme seems another example of the left hand not knowing what the right is doing: the RAE were making various attempts to upgrade Black Arrow yet never appear to refer to the Larch motor at all. Given that a lot of work had already been done on the chamber (but not on the full scale motors), it might seem a particularly cost-effective method of upgrading.26

The other proposal which RAE were working on at the time of cancellation was to attach four solid fuel Raven boosters to the first stage, with the empty cases being jettisoned after use. Again, the idea is similar – use the extra thrust to stretch the tanks.

Original: Proposed:

First Stage Burn time 127 seconds 200 seconds

Second Stage Burn time 117 seconds 180 seconds

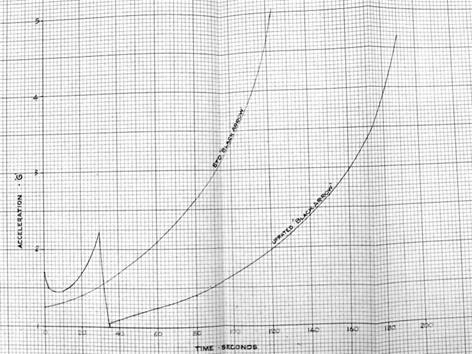

In this case, both the first and the second stage tanks have been extended. The result is an increase of payload to 470 lb, which is effectively double that of the unboosted vehicle. The graph in Figure 118, showing the acceleration of the vehicle, is rather interesting.27 At 34 seconds, the acceleration falls to zero! This is presumably when the Raven boosters have burned out, and the upwards kink in the graph after that is a consequence of the empty cases being jettisoned. It showed that the RAE had stretched the vehicle as far as it can possibly go, and any further weight increase would have been a considerable embarrassment!

|

Figure 118. Graph showing acceleration versus time for Black Arrow with and without boosters. |

One final suggestion on improving Black Arrow came from Saunders Roe: a vehicle called SLAVE.

Rather mundanely, this abbreviation stood for Satellite LAunch VEhicle. It was a Saunders Roe proposal dated around 1970, produced independently of RAE, and suggested using four of the large Stentor chambers for the first stage. The first stage could then be stretched correspondingly.

The idea was similar to BSE’s proposal of some years previously, although there was no other connection between the two ideas. The second and third stages would have been unchanged.

This would have probably given the greatest payload of the three proposals outlined here, although developing the four chamber motor for the first stage would not have come cheap. It also had the advantage that there was still some ‘stretch’ left in the design.

On the other hand, none of these ideas address the basic issue: what was the point? If there were no satellites to be launched, then there was little point in ‘stretching’ a vehicle which had run out of uses. The whole Black Arrow saga shows the confusion running through British space policy, and how a rather dubious decision taken in 1964 limped on for another seven years before being cancelled. Again one is tempted to say: do the thing properly, or don’t do it at all.

On the other hand, none of these ideas address the basic issue: what was the point? If there were no satellites to be launched, then there was little point in ‘stretching’ a vehicle which had run out of uses. The whole Black Arrow saga shows the confusion running through British space policy, and how a rather dubious decision taken in 1964 limped on for another seven years before being cancelled. Again one is tempted to say: do the thing properly, or don’t do it at all.