POWER FAILURE

There was eagerness for the final Block II to provide close-up pictures and radar reflectivity of the Moon’s surface, as well as (hopefully) seismometry. Ranger 5 had been scheduled for June 1962, but was postponed to allow the first pair of Mariner interplanetary missions to be dispatched in July and August.

On 30 August Rolph Hastrup, in charge of sterilisation, recommended that heat – treatment not be applied to the Block III. The use of ‘clean rooms’ to assemble the spacecraft, and the infusion of gaseous ethylene oxide to sterilise it within the Agena shroud shortly prior to launch should be continued. Clifford Cummings postponed a decision until after the next mission.

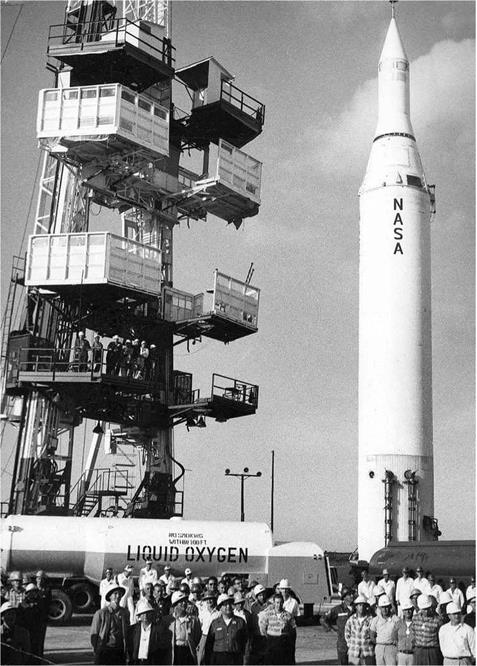

Ranger 5 arrived at the Cape on 27 August. As a result of recent modifications, it was about 10 kg heavier than its predecessors. The countdown on 16 October was scrubbed when a short circuit occurred in the spacecraft’s radio system. A launch the next day was ruled out by high winds. The mission got underway at 18:00 GMT on 18 October. Despite suffering a glitch, the Atlas responded to steering commands from the Cape, and the Agena achieved the desired parking orbit. This time, tracking ships were stationed in the Atlantic in order to provide continuous monitoring of the spacecraft’s telemetry. It had been decided that if the trajectory from the Agena’s second burn were to be beyond the spacecraft’s ability to correct, then the scientific priority would be to obtain gamma-ray data, rather than to snap flyby pictures of the Moon. This was because the Block III would provide TV, whereas there would be no gamma-ray spectrometers on any spacecraft that would head into deep space any time soon. The Agena made the translunar injection and released its payload. For the first time, the Deep Space Instrumentation Facility had two missions to keep track of in space. Mariner 2 was cruising to Venus, but the lunar mission would have priority call on resources during its 3-day flight.

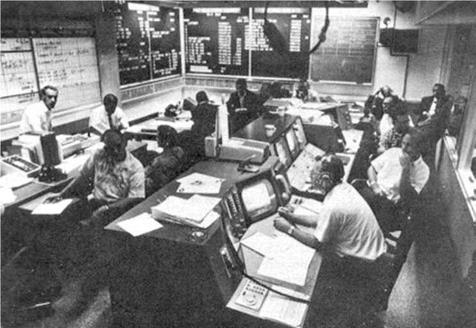

When the Woomera tracking station acquired Ranger 5, it had deployed its solar panels and locked onto the Sun. The next task was to roll in order to acquire Earth as the second point of reference. But the temperature in the power switching and logic module of the computer/sequencer rose sharply and power from the solar panels was lost – there had been a short circuit. Patrick Rygh had replaced Marshall Johnson in charge of the Space Flight Operations Center, to free Johnson to manage the design and construction of the new Space Flight Operations Facility. James Burke, at the Cape, directed Rygh to have the spacecraft make a midcourse manoeuvre before its battery expired, to ensure that it would hit the Moon. But because the spacecraft had not acquired Earth its actual orientation in space was indeterminate. It was therefore decided to set up the manoeuvre using only the Sun as a reference. A command was uplinked to gimbal the high-gain antenna away from the nozzle of the engine on the base of the bus. The spacecraft initiated the ad hoc 30- minute manoeuvre sequence, but before it could be completed the transmitter fell silent. It appeared that electrical shorts had drained the battery. The Moon was ‘last quarter’ on 20 October. The inert vehicle flew by the trailing limb on 21 October at an altitude of 720 km and passed on into solar orbit – its progress once again being tracked by the transmitter in the surface package.

On 22 October W. H. Pickering ordered an investigation staffed by JPL personnel who were not involved in the project. When this issued its report on 13 November, it lamented that the mass limit imposed on the Block II prevented it from having any redundancy – in order to achieve its mission, the spacecraft required every system to

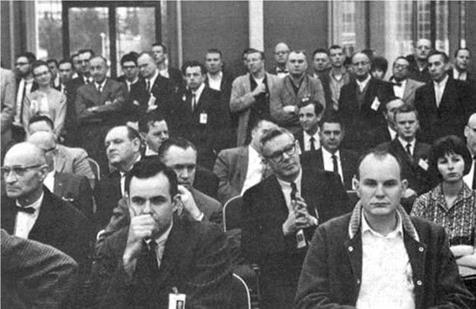

|

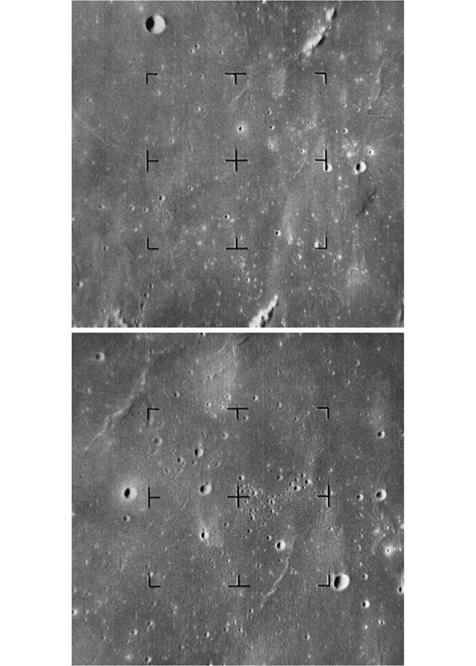

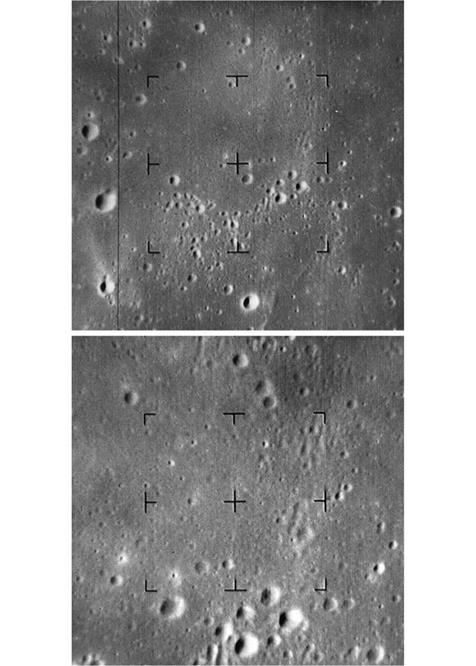

The Space Flight Operations Center at JPL during the Ranger 5 mission, with Patrick Rygh in command. |

work. Burke was criticised for (in the opinion of people not involved) having spent too much of his time on launch vehicles, launch operations and space experiments, as opposed to the spacecraft. Burke was also criticised for the importance he gave to meeting schedules. However, in this he had merely been reflecting NASA’s desire to get ahead of the Soviets within the 36 months that had been assigned to the project. The structure of JPL was also criticised, in that engineers assigned to work on flight projects by the technical divisions often lacked vital experience, and section chiefs unfamiliar with either the project management or the subsystems that their engineers worked on had inadequately reviewed this work. Remarkably, despite the fact that a lack of commonality in the failures implied a reliability issue in the components, the investigation did not address the issue of heat sterilisation, and Hastrup’s memo to Cummings was not discussed. The report concluded that the Block III was unlikely to perform any better. To remedy the situation, it recommended (in part) that Burke be replaced and that his successor review the Block III design, add redundancy, and introduce new project management, inspection and testing procedures.

Neither of the two Block Is had achieved the intended high-apogee orbits (owing to Agena problems) and only one of the three Block Ils had reached the Moon (in an inert state). The project had been acknowledged to be technologically risky when it was commissioned, but no one had expected such poor performance. The spacecraft failures undoubtedly resulted from heat-sterilisation. The only scientific result from the entire exercise was provided by the gamma-ray spectrometer of Ranger 3, which established the existence of ‘hard’ radiation in space. However, absolutely nothing had been learned about the Moon. Nevertheless, the sense of ‘crisis’ would not have come about if the final Block II mission had been a complete success.

Responding to the mood, Homer Newell asked Oran Nicks to establish a Board of Inquiry to review the past performance and future prospects of the Ranger project. It was chaired by Albert J. Kelley, Director of the Electronics and Control Division of the Office of Advanced Research and Technology, and drew its membership from headquarters, field centres not involved in the project, and analysts from Bellcomm Incorporated – a systems engineering group established by the American Telephone & Telegraph Company in March 1962 at the request of the Office of Manned Space Flight to conduct independent analyses in support of Apollo. In particular, it was to submit recommendations ‘‘necessary to achieve successful Ranger operation’’. No thought was given to cancelling the project, because the high-resolution TV from the Block III was required for Apollo. On 30 November the Board issued its report. As regards JPL, it said that because the laboratory was attempting to use a common bus for its lunar and planetary projects, Ranger was more complex than strictly required, and as yet the high order of engineering skill and fabrication technology required for this not to represent an issue had yet to be achieved. It also said that the degree of ground testing was inadequate – the laboratory’s tradition with military missiles was to iron out problems by test flights; this was impractical with spacecraft. The Board judged heat sterilisation to have been a significant factor in the failure rate. Of course, the lack of redundancy in the spacecraft was criticised. JPL was also criticised for trying to run such a major venture simply by superimposing a small project office on top of its divisional structure. The recommendations therefore included strengthening the project office at JPL and revising the procedures for design review, design change control, testing and quality assurance. Heat sterilisation should cease. The Block III objectives should be restated, and all activities which did not directly contribute put aside. If additional versions of the spacecraft were required, then JPL should hire an industrial contractor.

On 7 December 1962 JPL relieved both Clifford Cummings and James Burke of their posts. On 12 December, Brian Sparks, Deputy Director of the laboratory, led a delegation to Washington to discuss the Kelley report with Homer Newell. At this and a second meeting on 17 December it was decided (in part) to delete the eight particles and fields experiments which Newell had added to the Block III in March; to discontinue heat sterilisation and the use of gaseous ethylene oxide; to discard all heat-treated hardware; and that (as originally intended) the sole goal of the Block III would be to obtain high-resolution TV of the lunar surface in support of Apollo. On 21 January 1963 William Cunningham, the Ranger Program Chief at headquarters, told the scientists that their experiments had been deleted from the Block III and, to ease the blow, pointed out that they would be favourably considered for carriage on possible future missions.

Morale at JPL was boosted on 14 December 1962 when Mariner 2 made a close flyby of Venus and became the first deep-space mission to make in-situ observations of another planet, along the way establishing that the solar wind was ‘gusty’.

On 18 December Robert Parks superseded Cummings, and Harris Schurmeier was made Ranger Project Manager – having been Chief of the Systems Division that had handled most of the work, he was the obvious choice. He immediately instituted a Ranger System Design Review Board involving Burke (who remained on the project staff), Gordon Kautz, Allen Wolfe and section chiefs of the supporting engineering divisions. Its primary task was to increase reliability by identifying and eliminating potential weak points in subsystems. The deletion of the experiments from the Block III released 22.5 kg of mass to accommodate redundancy. The enlarged solar panels were retained to provide a healthy power margin. Meanwhile, Bernard P. Miller of the Radio Corporation of America held a thorough review of the high-resolution TV package and recommended that the various wide-angle and narrow-angle cameras, together with their associated electronic assemblies, be split into two independent electrical chains so as to ensure that some pictures would be obtained even if an electrical problem were to disable one chain. Furthermore, to guard against the failure of the computer/sequencer, Miller recommended that a backup timer be added to start the TV system. Schurmeier accepted these recommendations. He also duplicated the gas supply of the attitude control system, and increased the capability of the main engine to make the Block III better able to correct a discrepancy in the translunar injection. And as arcing discharges were the single most worrisome cause of in-flight failures, he ordered that plastic covers be placed over all exposed terminals. W. H. Pickering strengthened the project office by revising the lines of authority and responsibility within the technical divisions so as to make the section chiefs personally involved in project activities, accountable for the quality of their engineers’ work, and no longer able to reassign personnel without the consent of the project manager. Pickering also made Ranger the laboratory’s highest priority flight project – thereby guaranteeing Schurmeier the authority he needed (and Burke had lacked) to drive work through in the manner desired. On 13 February 1963 NASA approved the long list of changes to be made to the Block III. In October the schedule for Block III was set, calling for missions in late January, March, May and July 1964.

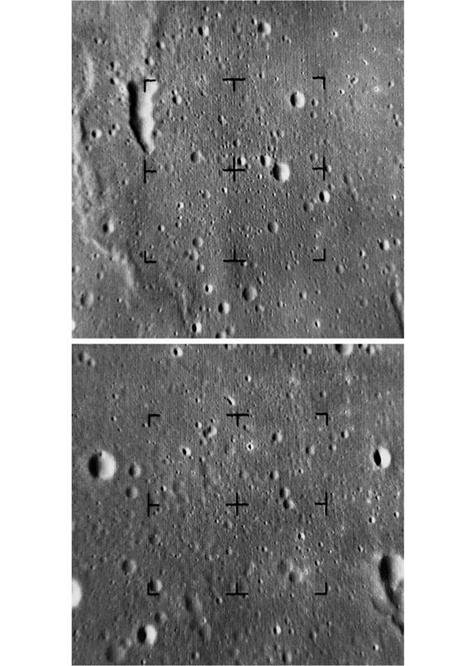

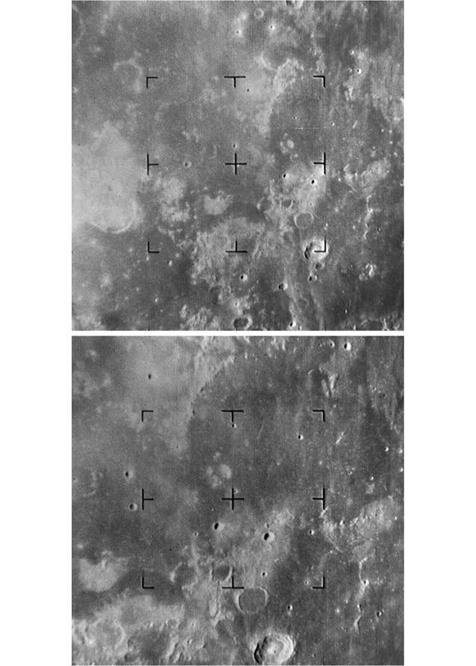

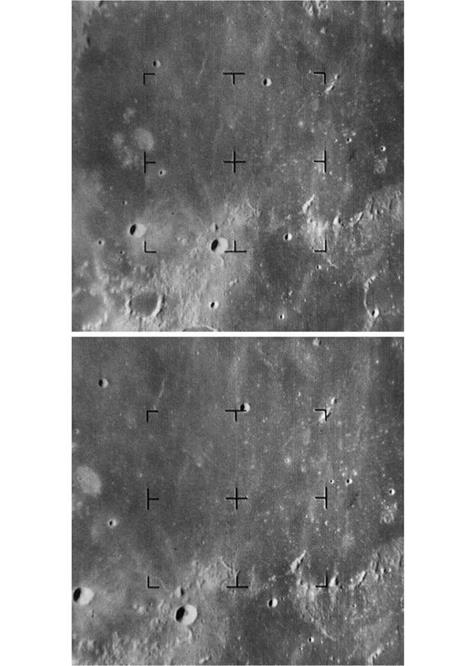

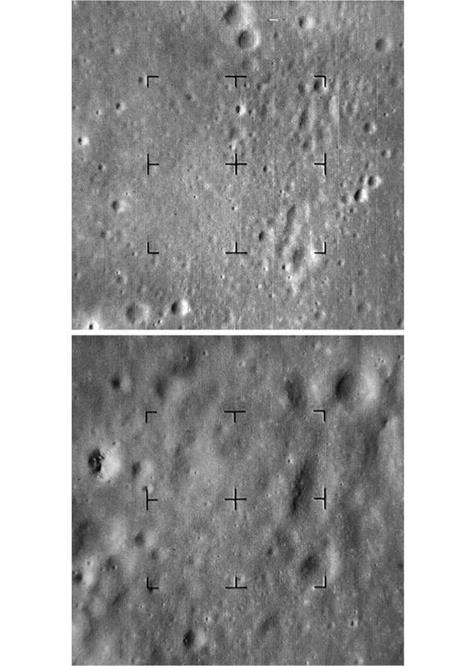

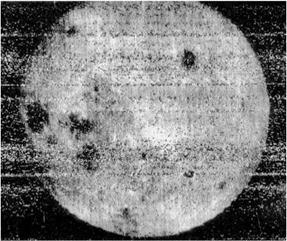

out to emphasise detail. In the wide lens the lunar disk spanned 10 mm, and in the narrow lens it was 25 mm.

out to emphasise detail. In the wide lens the lunar disk spanned 10 mm, and in the narrow lens it was 25 mm.