SATELLITE SHOCK

The first International Polar Year was held between 1882 and 1883 to coordinate meteorological, magnetic and auroral studies. The eruption of Krakatoa in

Indonesia on 20 May 1883 had a temporary but significant effect on the atmosphere. A second International Polar Year was held 50 years later. In 1950 the International Council of Scientific Unions proposed to exploit the technologies developed in the years since the Second World War to undertake geophysical research on a global basis to study the solar-terrestrial relationship. In early 1952 it was agreed that this International Geophysical Year would run from July 1957 to December 1958, a period which was expected to coincide with the time of maximum solar activity in the 11-year cycle of sunspots. In early 1954 the National Security Council said the US “should make a major effort during the International Geophysical Year”, and directed the Pentagon to provide “whatever support was necessary to place scientists and their instruments in remote locations” to make observations.

In August 1953 physicist Fred Singer outlined to the International Congress of Astronautics a 45-kg satellite for MOUSE (Minimum Orbital Unmanned Scientific Experiment). He spent the next year promoting it. In October 1954 he canvassed the US delegation to the meeting in Rome, Italy, of the International Geophysical Year’s Steering Committee, and as a result a resolution was passed which encouraged participants to investigate the possibility of launching a satellite as the highlight of the program.

In November 1954 Charles Wilson told journalists he did not care if the Soviets were first to put up a satellite. Despite the National Security Council directive for “a major effort’’ in support of the International Geophysical Year, it was not until 1955 that Wilson endorsed a satellite. In July 1955 Eisenhower announced that the US would put up a satellite for the International Geophysical Year. Eisenhower saw it as a one-off scientific venture. He assigned to the Pentagon the decision for how it should be achieved. There was intense rivalry between the services, because such a spectacle would boost that service’s claim to be assigned a greater responsibility for long-range missiles. Shortly before Eisenhower’s announcement, Donald Quarles, Chief of Research and Development at the Pentagon, had set up a committee chaired by Homer Joe Stewart, a physicist at the University of California at Los Angeles, to review the capabilities of the services. The National Security Council had stipulated that the satellite must not impede the development of the Atlas missile, which was only now beginning to gear up as a ‘crash’ national program. This ruled out the Air Force.

The Army proposed Project Orbiter, claiming that if the Redstone missile, which was an improved V-2, were to be fitted with three upper stages, a satellite would be able to be launched by January 1957, which was before the start of the International Geophysical Year. The Navy had Project Vanguard, in which an improved form of the Viking ‘sounding’ rocket introduced in 1949 for stratospheric research would be augmented with two upper stages. Part of the rationale for the Stewart Committee selecting Vanguard was the perceived greater reliability of requiring only two upper stages, instead of three. In addition, the Committee was impressed by the in-line configuration of the Vanguard stages, as opposed to clustering small solid rockets to form the upper stages of the Redstone launch vehicle. Nevertheless, Stewart himself had supported the Army’s proposal. One factor was that whereas the Redstone was a weapon and was classified, the Viking was not classified. Another rationale, added later, was that it would be better to use a ‘civilian’ rocket for this scientific project. The Committee was not concerned that Vanguard would not deliver as early as the Army claimed for Orbiter – it was simply presumed that the first satellite would be American, and provided that it was launched within the period of the International Geophysical Year it would serve its purpose. On 9 September 1955 the Pentagon endorsed the Committee’s recommendation. The spherical Vanguard satellite would weigh about 1.5 kg, and would transmit a radio signal that would allow the study of electrons in the ionosphere and thus make a unique contribution to the International Geophysical Year.

Since the services were only loosely controlled by the Department of Defense, the Army set out to contest the decision, emphasising that the Redstone could launch a satellite without impeding military work. When on the Stewart Committee, Clifford C. Furnas of Buffalo University had sided with the Army. Now at the Pentagon, he advised the Army to have its missile ready as a backup in case Vanguard faltered.

On 1 February 1956 the Army Ballistic Missile Agency was established at the Redstone Arsenal, Major General John B. Medaris commanding. It was to develop an intermediate-range ballistic missile named Jupiter. As the warhead would enter the atmosphere at a faster speed and be subjected to greater heating than that of the short-range Redstone, it was decided to test the new re-entry vehicle by firing it on a ‘stretched’ Redstone equipped with two upper stages made by clustering small solid rockets. The fact that this ‘Jupiter-C’ would enable the Army to develop and test a vehicle capable of launching a satellite was, of course, entirely coincidental! When the first test flight on 20 September 1956 reached a peak altitude of 1,000 km and flew 4,800 km down the Air Force’s Eastern Test Range from Cape Canaveral, the Pentagon directed Medaris to personally guarantee that Wernher von Braun did not inadvertently place anything into orbit! One criticism of Vanguard was that although its first stage was based on the Viking, the project really involved developing a new integrated vehicle in a period of only 2 years. With Vanguard running late, Medaris sought permission to launch a satellite, but the Secretary of the Army refused – in fact, the Army Ballistic Missile Agency was ordered to destroy the remaining solid rockets obtained for the upper stages. In response, Medaris decided to leave them in storage to ‘assess’ their shelf life!

In public, Eisenhower maintained that launching a satellite was a one-off venture for the International Geophysical Year. In fact, this was a cunning ruse, because the aim was to use Vanguard to set the precedent of a US satellite passing over foreign territory, and thus preclude a legal challenge when the US began to send up satellites for military functions such as reconnaissance.

Soon after the US announced that it would launch a satellite for the International Geophysical Year, the Soviet Union said it intended to do the same. In mid-1957 the Soviet magazine Radio told its readers how to go about ‘listening’ to this satellite. In late August the TASS news agency announced the successful test flight of a ‘‘super long range’’ missile which was capable of striking ‘‘any part of the world’’. When a Soviet delegate at an International Geophysical Year meeting in Washington in late September was asked whether the promised satellite was imminent, he replied: ‘‘We won’t cackle until we’ve laid our egg.’’ In other words, wait and see!

On 4 October the 84-kg Sputnik was placed into an orbit which ranged in altitude between 220 and 950 km and transmitted its incessant ‘beep, beep, beep’ signal.

The news caused a world-wide sensation, but Eisenhower was not concerned. At a press conference on 9 October he dismissed Sputnik as a ‘‘small ball in the air’’ that ‘‘does not raise my apprehensions, not one iota’’. On the other hand, the mass of the satellite showed the capability of the Soviet intercontinental-range ballistic missile, and Eisenhower ordered an end to the administrative difficulties that were impeding funding for the American missile programs.

Lyndon Baines Johnson was not only the senior Democratic senator for Texas, as the Democratic leader in the Senate he essentially controlled majority congressional support for the legislative program: put simply, without his backing, the Republican administration was ineffective. Johnson saw Sputnik in terms of national security – the satellite could well have been an orbital bomb, waiting to be instructed to fall on an American city. He ordered a Congressional investigation into the state of national security preparedness. As a result, the public became aware that there was a ‘‘missile gap’’; and, almost overnight, ‘space’ was transformed from a fantasy into something that the US should be leading, since otherwise national prestige would be damaged.1

After the launch on 3 November of a heavier Sputnik with a canine passenger, Eisenhower demanded an increase in the pace of Vanguard, which was in trouble, and also authorised the Army Ballistic Missile Agency to prepare a Jupiter-C in case Vanguard should fail. Medaris had the solid rockets for the upper stages retrieved from storage and let von Braun loose.

On 6 December 1957 Vanguard ignited, lifted a few centimetres off the pad, then collapsed back and exploded in a fireball. On 31 January 1958 the Army launched a satellite using essentially the same vehicle configuration as the Stewart Committee had rejected. On being asked for permission to inform Washington of the success, Medaris reputedly said: ‘‘Not yet, let them sweat a little.’’ The satellite, Explorer 1, was integrated into the solid rocket of the final stage and inserted into an orbit which ranged between 360 and 2,550 km. The Geiger-Mueller tube it carried was supplied by James van Allen, a physicist at the University of Iowa, and detected the presence of charged-particle radiation trapped within the Earth’s magnetic field, far above the atmosphere.

With the development of nuclear-armed intercontinental-range ballistic missiles threatening to make manned strategic bombers obsolete, the Air Force reacted to the prospect of its strike force becoming ‘silo rats’ by claiming that it needed to develop a manned space flight capability. Its Ballistic Missile Division, headed by General Bernard Schriever, devised Man In Space Soonest. This envisaged a progression of steps that would result in an Air Force officer landing on the Moon in 1965. When this was submitted to the Pentagon in March 1958 the response was lukewarm – in

|

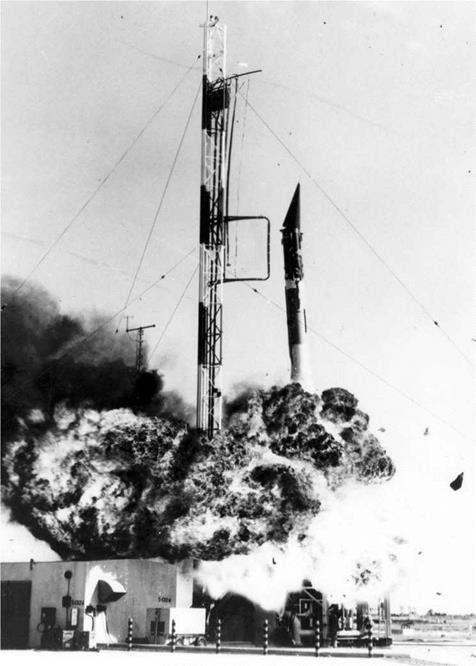

On 6 December 1957 the Vanguard rocket explodes within seconds of ignition. |

|

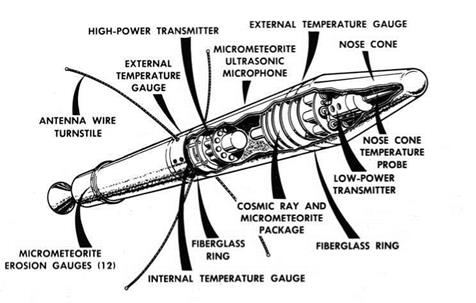

Details of the Explorer 1 satellite, with the instrument section integrated with the solid – rocket final stage. |

part owing to the estimated cost of $1.5 billion, but also due to the absence of a clear military necessity. In fact, the proposal was an example of what would be referred to in today’s parlance as a demonstration of ‘the vision thing’.

No sooner had the Army developed its Jupiter intermediate-range ballistic missile than the Pentagon assigned operational control of all land-based missiles with ranges exceeding 320 km to the Air Force, thus limiting the Army to ‘battlefield’ missiles. In fact, the Air Force had no use for the Jupiter, since it had just developed its own Thor intermediate-range ballistic missile.

The only prospect for the Army Ballistic Missile Agency was therefore to develop powerful launch vehicles for satellites. On 19 December 1957 the Army proposed the National Integrated Missile and Space Vehicle Development Program. Like the Air Force, the Army saw itself as the obvious service to explore space. In 1959 it proposed Project Horizon to achieve a manned lunar landing in 1965, but this was received no more enthusiastically than the rival Man In Space Soonest.