Performance Goals

When the United States entered the Second World War in December 1941, the venerable twin-engined Douglas DC-3 was standard equipment. On the domestic front, only T. W.A. had a better airliner, the four-engined Boeing 307. It was faster than the DC-3 (220 v. 160 mph) and far more comfortable, flying as it did ‘above the weather’ (20,000 v. 8,000 feet). But its range was not outstanding.

Dramatic Debut

In 1927, Charles Lindbergh’s solo trans-Atlantic flight changed the air-mindedness of an entire nation: the press, the public, the politicians, and the industrialists. In 1944, the airline world was unexpectedly confronted with another record flight, with almost comparable consequences. With one dramatic gesture, Howard Hughes electrified the political scene in Washington, and changed the course of progress in commercial aviation technology.

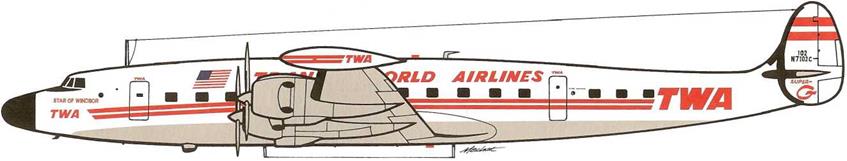

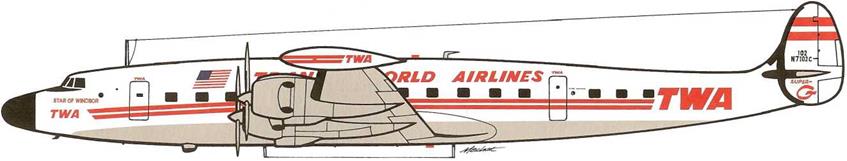

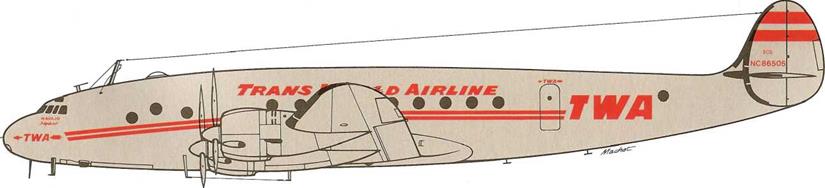

The Lockheed Constellation had been built at Burbank under the direction of designer Hal Hibbard to the precise specifications of Hughes, whose experience as an aviator and industrialist, with instinctive intuition, combined with his extensive financial resources, were injected into the design and construction of an historic prototype.

Moment of Triumph

On 17 April 1944, Howard Hughes and Jack Frye flew the prototype Model 49, soon to be called the Constellation, from Burbank to Washington’s National Airport in the transcontinental record time of 6 hours, 57 minutes. The effect on a skeptical administration and military hierarchy was startling. After flying some congressmen and top military brass on sightseeing flights, Hughes turned the new airplane over to Air Transport Command. T. W.A.’s owner and Lockheed’s design team had ushered in a new era in air transport.

America’s Secret Weapon

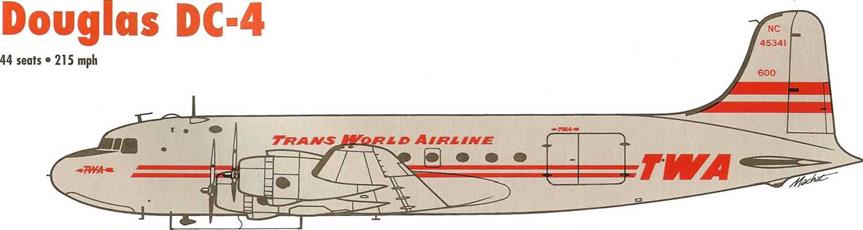

The Constellation reinforced the supremacy of United States aeronautics. Peter W. Brooks, distinguished British airline historian, described the aircraft as “the secret weapon of American air transport.” He pointed out that in 1939, at the outbreak of the Second World War, the British aircraft industry, whose technical talent was possibly on a par with the American, in quality if not in quantity of production, had regarded the DC-4 as the competitive standard. But when the War was over, the Constellation swept all before it.

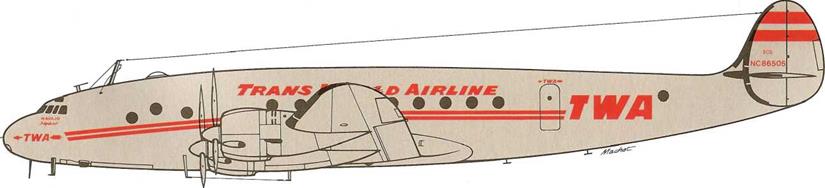

The 049 Constellation was similar in appearance to the later 749 model, differing only in window configuration and engine cowling detail.

Initial Snags

T. W.A. acquired 88 of the standard Constellations. Six were ex-military C-69s; 41 were Model 49s (later amended to 049s); and the remaining 41, with more powerful engines, Model 749s. The inauguration of Atlantic services, on 5 February 1946, is described on page 50. Domestic services with the Connie began ten days later, and after preliminary trial services on shorter routes, coast-to-coast service from New York to Los Angeles began on 1 March. But the satisfaction was short-lived. During the early life of the airplane, several problems had had to be overcome. The substantially increased performance carried with it increased complexity, and the Constellation was not immune from the technical ‘teething troubles.’ Then, from 12 July to 20 September 1946, the fleet was grounded because of a leaking fuel system. No sooner was this fixed when the pilots went on strike, from 21 October to 15 November.

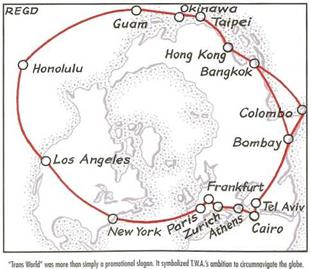

Ambition Fulfilled

By this time, however, T. W.A. was staking its claim to be a fully-fledged international airline. The European routes were extended to Cairo on 1 April 1946, to Lisbon and Madrid on 1 May, and to Bombay on 5 January 1947. All these were inaugurated with the Constellations. This fine airliner, in spite of an initial reputation of unreliability, soon got into its stride. It was 70 mph faster than the DC-4, had 60 seats against 44 at the same seat pitch, and could fly across the Atlantic with only one stop instead of two. It sent the Douglas designers and engineers back to their drawing boards in a hurry, to produce pressurized variants of the old Skymaster.

Many airlines purchased the Constellation, and although the DC-4 filled the bill for a postwar year or two, most of the trans-Atlantic airlines had the Lockheed airliner in service by the late 1940s. The British airline, B. O.A. C., had to have them too, as the home industry’s commercial airliner projects had been cancelled at the outbreak of the War in 1939.

But until the advent of the Jet Age in 1958, the world of airlines watched T. W.A. as it successively introduced newer and faster versions of the classic Constellation series.

Engines Wright R-3350 (2,200 hp) x 4 Length

MGT0W 86,250 lb. Span

Max. Range 3,000 miles Height

‘This aircraft made T. WA.’s inaugural trans-Atlantic flight, New York-Gander-Shannon-Paris (Le Bourget) on 5 Feb 46, in a block-to-block time of 19 hr 46m. NA: Sold to Nevada Airmotive, 31 March 1962

*This aircraft made TWA’s last scheduled commercial Constellation flight, Flight 249, on 6 April 1967. AT: These aircraft sold to Aero-Tech Inc. in May, June, and August 1968.

This is a listing of all the 87 Constellations in T. W.A.’s fleet. From the first famous delivery flight to Washington on 17 April 1944 to the last one by T. W.A. on 6 April 1967, 23 years had elapsed. This was, in the period of the piston- engined airliners, an impressive record. The list does not include the Super Constellations and Starliners, reviewed in the following pages.

|

|

|

Although the 600-gallon tip tanks gave the ‘Super G’a distinctive appearance, not all ofTWA’s 1049Gs were so equipped. Tip tanks were used primarily for international routes.

|

|

|

Fleet

No.

|

Regn.

|

MSN

|

Date into Service

|

Name

|

Disposal and Remarks

|

|

Series 1

901

902

903

904

905

906

907

908

909

910

|

049 (Mode

N6901C N6902C N6903C N6904C N6905C N6906C N6907C N6908C N6909C N6910C

|

1049-54-£

4015

4016

4017

4018

4019

4020

4021

4022

4023

4024

|

0)

9 Oct. 52 16 Aug. 52 16 Aug. 52 27 Aug. 52

2 Oct. 52 27 Sep. 52 18 Oct. 52 27 Sep. 52 26 Oct. 52

3 Nov. 52

|

Star of the Thames Star of the Seine Star of the Tiber Star of the Ganges Star of the Rhone Star of the Rhine Star of Sicily Star of Britain Star of Tipperary Star of Frankfurt

|

Sold to California Hawaiian, 28 Oct. 60 Crashed in the Grand Canyon, 30 Jun. 56 Sold to South Pacific Airlines, 1 Jun. 62

| Sold to Florida State Tours, 7 Aug. 64

Sold to California Airmotive, 15 Feb. 60 Crashed, New York City, 16 Dec. 60

| Sold to Florida State Tours, 7 Aug. 64

|

|

Series 1

|

049G (Mot

|

el 1049G-82-110)

|

|

|

|

101

|

N7101C

|

4582

|

21 Sep. 55

|

Star of Balmoral

|

Crashed at Chicago (Midway), 29 Feb. 60

|

|

102

|

N7102C

|

4583

|

17 Mar. 55

|

Star of Windsor

|

Temporarily named The United States. Flew inaugural Super

|

|

|

|

|

|

G service, 30 March 1955. Scrapped, 4 Feb. 64

|

|

103

|

N7103C

|

4584

|

14 Mar. 55

|

Star of Buckingham

|

Sold to Aaron Ferer & Sons, 3 May 65

|

|

104

|

N7104C

|

4585

|

17 Mar. 55

|

Star of Blarney Castle

|

Sold to Aaron Ferer & Sons, 1 Sep. 65

|

|

105

|

N7105C

|

4586

|

14 Mar. 55

|

Star of Chambord

|

Sold to California Airmotive, 12 Dec. 66

|

|

106

|

N7106C

|

4587

|

23 Apr. 55

|

Star of Ceylon

|

Sold to California Airmotive, 4 Jan. 67

|

|

107

|

N7107C

|

4588

|

1 Apr. 55

|

Star of Carcassome

|

Scrapped 7 Nov. 63

|

|

108

|

N7108C

|

4589

|

31 Mar. 55

|

Star of Segovia

|

Sold to Aaron Ferer & Sons, 25 Jun. 65

|

|

109

|

N7109C

|

4590

|

21 Apr. 55

|

Star of Granada

|

Sold to California Airmotive, 10 Nov. 61

|

|

110

|

N7110C

|

4591

|

8 May 55

|

Star of Escorial

|

Scrapped 14 Apr. 64

|

|

ж

|

N7111C

|

4592

|

10 May 55

|

Star of Toledo

|

Sold to California Airmotive, 4 Jan. 67

|

|

112

|

N7112C

|

4593

|

11 May 55

|

Star of Versailles

|

Sold to California Airmotive, 5 Dec. 66

|

|

113

|

N7113C

|

4594

|

11 May 55

|

Star of Fontainebleau

|

Sold to California Airmotive, 15 Feb. 67

|

|

114

|

N7114C

|

4595

|

2 Jun. 55

|

Star of Mont St. Michael

|

Sold to Aaron Ferer & Sons, 13 Jul. 65

|

|

115

|

N7115C

|

4596

|

29 May 55

|

Star of Chilton

|

Crashed at New York (JFK) 26 Jan. 66

|

|

116

|

N7116C

|

4597

|

4 Jun; 55

|

Star of Heidelberg

|

Scrapped 8 Apr. 64

|

|

117

|

N7117C

|

4598

|

5 Jun. 55

|

Star of Kenilworth

|

Sold to Aaron Ferer & Sons, 1 Oct. 65

|

|

118

|

N7118C

|

4599

|

9 Jun. 55

|

Star of Capri

|

Scrapped, 11 Jan. 64

|

|

119

|

N7119C

|

4600

|

1 Jul 55

|

Star of Rialto

|

Scrapped 10 Jun. 64

|

The aircraft said to Aaron Ferer & Sons were resold and scrapped at Tucson. The aircraft sold ta California Airmotive were scrapped at Fox Field, Lancaster.

|

|

|

Engines Wright 972TC Turbo-compounds (3,250 hp) x 4 Length 114 feet MGTOW 137,5001b. Span 123 feet

Max. Range 3,500 miles Height 25 feet

|

|

|

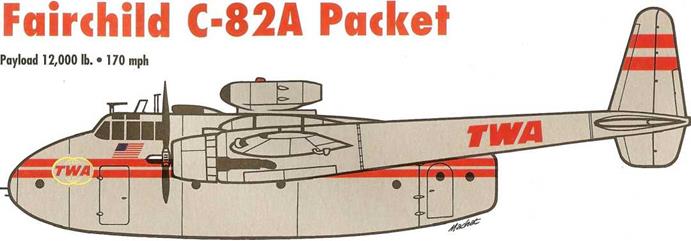

Engine Problems

Elegant though the Constellation was, and impressive though its performance, this fine airliner did have its problems, not least because its designers were always trying to advance the levels of technology. One of the main problems was the Wright R-3350 turbo-compound engines, which consistently gave trouble, to the extent that Claude Girard, the senior pilot of the relief truck, described on this page, claimed that the crews “logged more flying time on three engines than four.” At first, a C-47 was based in Paris to ship the piston engines to distant points, as T. W.A. had spread its wings to the far comers of Europe and southern Asia. But with the Jet Age approaching, with much larger engines, the decision was made to base a specialized engine-carrier in Paris.

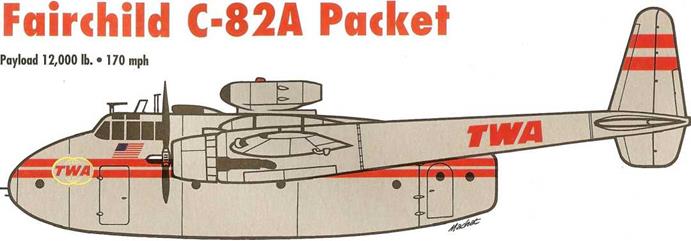

The C-82

Larry Trimble, T. W.A.’s operational chief in Paris, found the answer in a twin-boomed Fairchild C-82 Packet which he discovered in Tel Aviv in 1956. It took eight months of work, with much overtime, totalling 10,000 man-hours, to ‘civilianize’ the C-82. To increase the loadcarrying capability and airfield performance, a Westinghouse 3,250-lb- thrust J-34 jet engine was installed on top of the fuselage for auxiliary power, and to raise the take-off weight to 54,000 lb. A Volkswagen engine APU (auxiliary power unit) was also installed to power an electric windlass to haul aboard the disabled engines.

The Thing

The C-82’s performance was sluggish and the airplane was not easy to handle. Compared to the elegant Constellations, it was distinctly unhandsome. The crews named it Ontos, which is the Greek word for “Thing.” Ugly duckling it may have been; but it did its job well, entering service with T. W.A. In 1957, it was registered, as a matter of local convenience, ET-T-12, which had been the Ethiopian number for the displaced C-47. Ethiopian was one of the airlines that T. W.A. was closely associated with, either as part-owner or as technical and operational adviser. Eventually, Ontos was certificated by the F. A.A. on 1 March 1960, and registered as N9701F. It carried engines everywhere throughout the eastern hemisphere, flying regularly to Manila, Bombay, and Nairobi, with Constellation replacement engines. In 1968 alone, now hauling Boeing 707 engines too, there were 68 unscheduled overseas engine replacements

Artist’s Note

T. W.A. ’s C-82 was substantially modified fi-om its original post-World War Two configuration. Note the modern avionics antennae and J-34 jet engine pod mounted above the fiiselage.

|

Engines

|

Pratt & Whitney R2-800-85 (2,100 hp) x 2

|

Length

|

77 feet

|

|

NIGTOW

|

54,000 lb.

|

Span

|

107 feet

|

|

Range

|

500 miles

|

Height

|

26 feet

|

After twelve years of faithful service, un-noticed by the media as the Jet Age was augmented by the 747s and other more publicity-worthy wide-bodied giants, the “Thing” was retired on 13 January 1972, and sold the following year to an American airborne delivery firm, Briles Rotor & Wings.

|

I Photo courtesy Roger Bentley collection)

|

|

(picture courtesy Richard and Bernice DeGarmo, Al’s son, and daughter-in-law)

|

Air Mail Special

One of the more unusual of T. W.A.’s “firsts”is that, of all the airlines established in 1925 as the result of the Kelly Air Mail Act, it carried the first passenger. He was not even the official recipient of Western Air Express’s ticket No. 1 (see page 6) but he did precede Mr. Ben Redman, who had that privilege. Not only was Will Rogers the first passenger in T. W.A.’s 75-year history, he was the first famous personality of the dozens of celebrities who were later to make Howard Hughes’s company the Airline of the Stars.

The civil air mail regulations required that, before an airline could carry passengers, it had to carry the mail for 90 days, or at least for a trial period (see page 9). A1 DeGarmo, one of the Western’s legendary Four Horsemen (see page 10), was a friend of Will Rogers, then a vaudeville entertainer, noted for his prowess with rope tricks, later to become famous for his droll commentaries on the human condition. In a conspiracy that evaded the law — the lawyers would have had a lovely time in the courts — Will stuck a quantity of stamps on the back of his jacket and mailed himself to Salt Lake City and back.

In 1926, the pilots were not noted for their sartorial elegance, as they are today. But their attire was practical, and included a side-arm. This was to guard the mail, and in this case, presumably, to guard Will Rogers as well.

Los Conquistadores del Cielo

Another of T. W.A.’s lesser-known “firsts’ is that it inspired the foundation of that exclusive aviation club. The idea originated when in 1937 the airline obtained widespread support among political and business circles for its cut-off route to San Francisco, branching off northwestwards from Winslow, thus avoiding the circuitous route via Los Angeles and a connection on to Western Air Lines, via Las Vegas (see page 38).

President Jack Frye wanted to make a token reward to all the influential supporters who had enabled him to win approval for this important access to San Francisco. John Walker, Frye’s vice-president, suggested a weekend celebration in September 1937 for 60 guests at the Forked Lightning Ranch in Albuquerque. A great time was had by all, including horseback riding, fishing, and a dude rodeo — at which Jack Frye showed that he was no mean hand at roping steers, at least small steers.

The general consensus was “let’s do it again.” and John Walker once again came up with the idea of linking an annual event with the Spanish tradition of the south-western states, the locale of the cut-off route. And so was bom Los Conquistadores del Cielo, named after Francisco de Coronado, the Spanish conquistador who had annexed the whole area for Spain.

Jack Frye was elected president and 91 senior aviation aficionados were inducted on 16-18 September 1938 in a colorful initiation ceremony. This has been enhanced by a dress code, introduced by Walker in 1951: replicas of the raiment worn by Hernan Cortes and the original conquistadores. The Conquerors of the Skies meet every year, at different venues, in an elite association that owes its origins to a T. W.A. route extension.

|

(courtesy: Constance Walker)

|

|

(courtesy: Ona Gieschen)

|

Flooded Out

In July 1951, there was a great flood in the Missouri River valley, covering an extensive area of low-lying land around Kansas City, where the confluence with the Kansas River exacerbated the disaster. T. W.A.’s engineering base was then at the Fairfax airport (see page 107) which was vulnerable to flooding. In this picture a lone DC-3 can be seen stranded in the waters, but T. W.A. flew the other resident aircraft to higher ground.

|

(courtesy: Ona Gieschen)

|

Historic Greeting

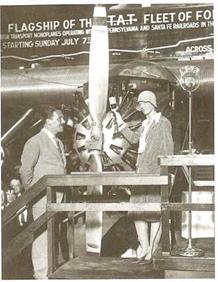

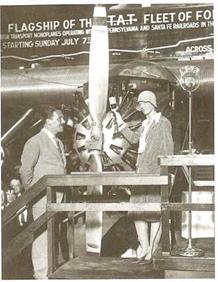

As narrated on page 52, one of the pivotal events in air transport history was the dramatic flight in 1944 of the first Lockheed Constellation, when Howard Hughes and Jack Frye delivered the prototype from Burbank to Washington in a transcontinental record time, (see page 52) They are pictured here on arrival at Washington’s National Airport with (left) William A. M.Burden, Assistant Secretary of Commerce; and Jesse Jones, Secretary of Commerce.

| |

Ray Dunn presides over a morning hour-long briefing in 1962 at the Mid Continent International Airport, where trouble-shooting was refined by long distance telephonic communication throughout the TWA system.

Ray Dunn presides over a morning hour-long briefing in 1962 at the Mid Continent International Airport, where trouble-shooting was refined by long distance telephonic communication throughout the TWA system.

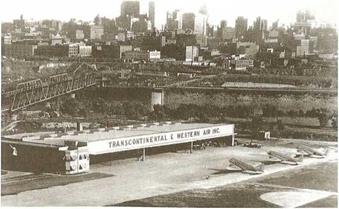

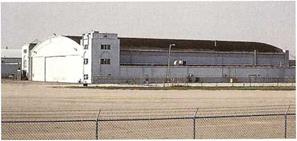

The building is still there. As one of the very few—and undoubtedly one of the most historically significant— 70-year-old architectural survivals of the formative years of air transport in the United States, it should be listed as an Historic Monument.

The building is still there. As one of the very few—and undoubtedly one of the most historically significant— 70-year-old architectural survivals of the formative years of air transport in the United States, it should be listed as an Historic Monument.

![Secret Weapon Подпись: Fleet No. Regn. MSN Delivery Date Name Disposal and Remarks Model 749A (Delivery 749A-79-52) 801 N6001C 2633 24 Mar 50 Star of New Jersey AT 802 N6002C 2634 11 Apr 50 Star of Kansas Renamed Star of Crete. Sold to C.E.Bush Aviation, 10 Dec 65 803 N6003C 2635 24 Apr 50 Star of Texas Renamed Star of America, AT 804 N6004C 2636 2 May 50 Star of Maryland Crashed and destroyed by fire near Wadi Natrun (50 miles north of Cairo, Egypt), 31 Aug 50 805 N6005C 2637 19 May 50 Star of New York AT 806 N6006C 2639 29 Jun 50 Star of Pennsylvania AT 807 N6007C 2643 18 Aug 50 Star of Ohio AT 808 N6008C 2644 7 Sep 50 Star of Indiana AT 809 N6009C 2645 11 Sep 50 Star of Michigan Sold lo AVIANCA, 10 Осі 59 810 N6010C 2646 20 Sep 50 Star of Illinois Renamed Star of Germany, AT 811 N6011C 2647 10 0(150 Star of Missouri AT 812 N6012C 2648 13 Oct 50 Star of Massachusetts Renamed Star of Spain, Sold to Federal Administration, 20 Jul 62 813 N6013C 2649 24 Oct 50 Star of New Mexico Renamed Star of Majorca, AT 814 N6014C 2650 3 Nov 50 Star of Delaware Sold to Central American Airways, 5 Oct 67 815 N6015C 2651 17 Nov 50 Star of Arizona Sold to C.E.Bush, 23 Mar 66. Repossessed 1967. AT [6 May 63] 816 N6016C 2654 12 Dec 50 Star of California Sold to Federal Aviation Administration 817 N6017C 2655 21 Dec 50 Star of the District of Columbia Leased to Pacific Northern Airlines, 17 Aug 61. Sold to Connie Air Leasing, 24 Nov 61 818 N6018C 2656 29 Dec 50 Star of Nevada AT 819 N6019C 2657 17 Jan 51 Star of Minnesota AT 820 N6020C 2658 25 Jan 51 Star of Kentucky AT* 821 N6021C 2667 17 Apr 51 Star of West Virginia AT 822 N6022C 2668 30 Apr 51 Star of Virginia Sold to Pacific Northern Airlines, 30 Jun 66 823 N6023C 2669 8 May 51 Star of Iowa AT 824 N6024C 2670 29 May 51 Star of Nebraska AT 825 N6025C 2671 Star of Colorado Fleet number and name allocated, but aircraft delivered to Hughes Tool Company. Sold to B.O.A.C, U.K.,23 Sep 54 826 N6026C 2672 29 Jun 51 Star of Connecticut AT 827 N86521 2642 1 Apr 54 Star of Oregon Delivered 12 Aug 50 to Chicago & Southern Airlines as City of Houston, then Cindad Trujillo. To Delta Air Lines, 1 May 53, with merger. Converted from Model 649A to 749A. Name later changed to Star of Colombo. AT 828 N86535 2673 20 Apr 54 Star of Wisconsin Delivered 18 May 51 to Chicago & Southern Airlines. To Della Air Lines, 1 May 53, with merger. Converted from Model 649A to 749A. Renamed Star of Corsica, then Star of Basra. AT 829 N86552 2653 1 Jun 54 Star of Washington Delivered 27 Sep 50 to Chicago & Southern Airlines. To Delta Air Lines, 1 May 53, with merger. Converted from Model 649A to 749A. Renamed Star of Madeira, then Star of Dhahran. AT](/img/1243/image238_0.gif)