90% on the Ground

The Embryo Years

In 1929 — the same year in which T. W.A.’s ancestor, T. A.T., was bom, Clement Keys, the head of the powerful North American Aviation group, delivered a speech in which he raised some eyebrows by stating that “90% of aviation is on the ground.” He was emphasizing that efficient and safe operations could only be achieved by good training, good aircraft and engine construction, and above all, good maintenance. In the 1920s, too many pilots were poor navigators and took too many risks; aircraft seldom lasted more than a few years; “the engine quit” was a familiar reason for a lucky escape in a meadow; and maintenance was a relatively casual affair.

Lindbergh’s Influence on T. W.A.

After Charles Lindbergh made his sensational New York-Paris non-stop flight in 1927, he followed this with a 48-State tour of the U. S.A., during which he vigorously promoted air travel. He became the technical consultant of T. A.T., subsequently T. W.A., and much of his advice concentrated on the vital need for ground support (see map on pages 28-29). At first, the aircraft were maintained mainly at Columbus, Ohio, and at Waynoka, Oklahoma, the transfer points during the brief period of the air-rail service (see pages 24-25). But after the need for the trains was eliminated in 1930, the airline established a single base at Kansas City, which became the heart of T. W.A.’s engineering organization.

Ray Dunn presides over a morning hour-long briefing in 1962 at the Mid Continent International Airport, where trouble-shooting was refined by long distance telephonic communication throughout the TWA system.

Ray Dunn presides over a morning hour-long briefing in 1962 at the Mid Continent International Airport, where trouble-shooting was refined by long distance telephonic communication throughout the TWA system.

Refining the System

During the 1960s, as the entire world of air transport transformed itself from knee-jerk reaction to systematic control of all facets of operation, T. W.A. was among the leaders in introducing progressive maintenance to take full advantage of the vast improvements in instant telephonic communication. Under the direction of Ray Dunn, vice-president of engineering, morning briefings were held every morning. These included up to 80 individuals, linked by telephone from coast to coast, exchanging reports of delays and problems, and discussing how to fix them. A fine example of the advances made during this time was the identification of engine snags. John Morelli, the manager of power plant engineering, was meticulous in checking the records of every engine, and identified a repetitive pattern of snags so that T. W.A. was able to put the principle of prevention being better than cure into practice. In 1969, T. W.A. instituted on-line inspections of some engine components, thus saving many engine changes and shipment of engines. Such initiative resulted in T. W.A. being the first airline to be approved by the F. A. A for on-condition maintenance of power plants.

Richards Road, Fairfax, and International

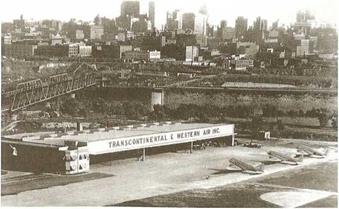

The first site at Kansas City was the Municipal Airport, in the heart of the city, in the horse-shoe bend of the Missouri River, often referred to as the downtown airport, but the employees usually called it “Number Ten, Richards Road”. T. W.A. had served the nation during the Second World War with its Intercontinental Division’s Boeing 307s (see page 46) and these were overhauled at Wilmington, Delaware. Also, just across the river from Richards Road, another base had been built in Kansas City, Kansas. This Fairfax base had been a modification center for B-25 bombers during the war. In 1946, T. W.A. moved in, and Richards Road was relegated for on-line maintenance only. In turn, when the new Mid-Continent International Airport was built, T. W.A. made another move, first, in 1956, with the Power Plant shop, then, in 1958, with the Airframe Shop as well.

|

This was the downtown, or Municipal airport, Kansas City, also known as 10, Richards Road. |

|

This rare picture of the hangar at 10 Richards Road shows a Fokker F32 (left) towering over a Ford Tri-Motor, which itself dwarfs a Northrop Alpha, with other Fords in the background. |

|

The former wartime modification center was the home ofTWA’s engineers from 1946 until 1956. It could accommodate the Constellations, which were much bigger than the DC-2s shown in the top picture, (all photos courtesy Ona Gieschen, Airline History Museum) |