Picking up the Pieces

T. W. A. set about the task of recovery, after the departure of Carl Icahn. In July 1993, William Howard had been named chairman and C. E.O., but he resigned in January 1994, to be replaced by Donald F. Craib, Jr. Some sense of purpose returned to the airline when Jeffrey H. Erickson was elected president in April. He had airline credentials, having started as a Pan American engineer, moved on to various airlines, and had launched the low-fare new entrant, Reno Air, in July 1992. He took action to restore confidence. Service was started from St. Louis to some mid-west points, as well as to Sacramento and Ontario. International service was restored to Saudi Arabia, where T. W.A.’s tradition went back a long way, having served Dhahran, on the Gulf, from July 1946 to May 1971. Now the terminus was Riyadh, the handsome capital, which has one of the world’s most beautiful terminal buildings. But service to Geneva and Zurich was terminated, and the Los Angeles-Paris Polar route was suspended, as these routes were just not paying their way.

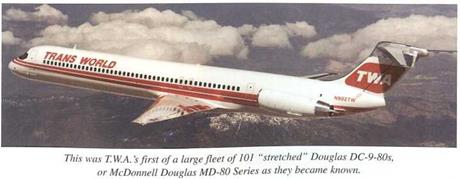

The employees responded, as best they could, supporting from their pay packets the $223,000 per month lease payments for a new McDonnell Douglas MD-83 (#9408) appropriately named Wings of Pride. Delivery was made at a proud ceremony on 2 September 1994.

But Pride is often accompanied by a Fall. By October, T. W.A. was asking its major creditors to “forgive” almost half of its $1.8 billion debt, in exchange for more equity. This would increase the creditors’ stake in the airline from 55% (the legacy of Carl Icahn) to 70%. But the creditors were wary, and in no hurry. T. W.A. was once again forced into a corner.

Chapter Eleven Again

When John Cahill was elected chairman of the board on 28 February 1995, the prospects were grim, and on 30 June, T. W.A. filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy for a second time. However, there was a silver lining. In August, the three unions agreed to $130 million per year savings in wages and through increased productivity, at the same time reducing their ownership in the airline from 45% to 30%. The wary creditors accepted the 70% shareholding in exchange for debt.

In February 1996, T. W.A. ordered 20 Boeing 757-200s, with options for another 10. They were to replace the Lockheed TriStars, which were becoming costly to maintain. The 757s had a common cockpit with the 767, another cost saving; and in the long term it was the beginning of a program of reducing the average age of the fleet.

Perry Flint, of Air Transport World, was encouraging: “Somehow, T. W.A. survived its near-death experiences and the long-awaited obituary never appeared… is in better shape than at any time in this decade.. . (it) has a sense of purpose, rising pride in its product, and a confidence bom of having survived the worst that man and nature could throw at it.”

The Cruel Hand of Fate

On 17 July 1996, Flight TW800, a Boeing 747, disintegrated at the eastern end of Long Island, still on its initial climb out of New York’s JFK Airport. The direct cause was the explosion of the center fuel tank, but the cause is not known for certain. After four years of research, the official explanation was that it might have been an inducted spark into low-tension wiring, but most aviation folk are skeptical.

In an interesting, though unfortunate, parallel, this disaster, which killed more than 200 people, occurred just when T. W.A.’s financial situation was improving; and was a tragic repetition of a similar situation in December 1988, when the Pan American 747 exploded at Lockerbie, Scotland, just when the airline was striving to recover its North Atlantic market share. In both cases, the effect on the travelling public’s perception was detrimental — to put it mildly.

Firm Hands at the Wheel

T. W.A. was undeterred. On 17 September it announced the acquisition of ten more MD-83s, making 15 in the fleet. Gerald Gitner became chairman and C. E.O., while Erickson retired. Gitner was joined, on 3 December 1997, by William (Bill) Compton, who became president and chief operating officer (C. O.O.). Bill was a veteran T. W.A. pilot, who had joined T. W.A. at the age of 21, had risen in the ranks to become the elected leader of the pilots’ union, ALPA, and had the distinction of having been furloughed three times. During T. W.A.’s turbulent years, the term distinction was indeed the operative word.

In 1995, the debt to Carl Icahn had been re-structured. T. W.A. agreed to pay off the debt by making available to Carl’s airline ticket agency the right to sell tickets. The arrangement was for eight years, and the airline will be relieved of the obligation in September 2003.

The Largest Order

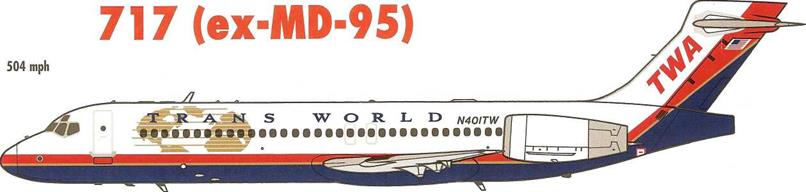

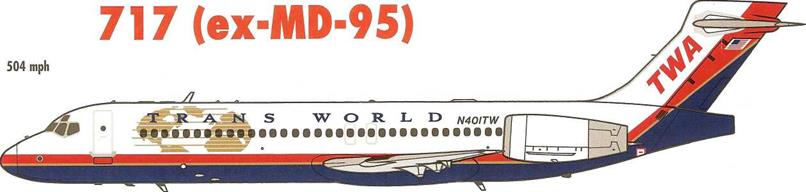

The year 1998 ended on a high note. In December, T. W.A. announced orders for 100 new airliners. The order comprised 50 111-seat Boeing 717-200s (formerly McDonnell Douglas

MD-95s) and 50 106-seat Airbus A318s. Both aircraft are at the lower stratum of jet airliner size, and will fulfill the need for the sparser traffic-generating routes, with considerably lower operating costs that those of the aircraft they replace. This was the first order for the A318 and one of the first for the 717, and T. W.A. was able to negotiate a good price, taking advantage of what is known in the industry as “launch economics.” T. W.A. also indicated its intention to order 25 more Airbuses, unspecified variants of the Airbus A320 family.

This acquisition — valued at around $4 billion, the largest in T. W.A.’s history — was marred slightly by the beginning of a “sick-out” by some flight attendants on Christmas Eve. They made a rapid recovery on the day after Christmas, by order of Judge Nina Gershon. But confidence was maintained in financial quarters in March 1999, when Boeing arranged $2.4 billion of financing to protect 82 unfilled T. W.A. orders, including the 717s.

Historical Precedent

In May 1999, Bill Compton was appointed C. E.O. as well as holding the office of president. Many years had passed since T. W.A. had been directed from the top from someone who had risen from within the ranks. As a pilot — he still kept his license current by taking the left-hand seat on an MD-83 flight deck from time to time — he enjoyed the respect of the flying crews. In his first months as CEO, he oversaw agreement on new contracts for all union-represented employees with pay increases that were mirrored by wage boosts provided to non-union workers as well. Although T. W.A. still trailed other major airlines’ pay scales, it marked the first time in 15 years that T. W.A. workers had been given more pay rather than more concessions in a contract.

Trans World Airlines moves into the twenty-first century in good spirits, even though its finances are still precarious. It has the best on-time record in the industry (“worst to first in three years.”) Its once old, almost time-expired, fleet (one Boeing 747 was retired with more than 101,000 hours flying time behind it) is being replaced by new aircraft, and the average fleet age is rapidly decreasing. Its loyal staff have increased productivity and the management is keeping its head. In the year 2000, T. W.A. celebrates its 75th anniversary, with a pilot up front, just as, in the great years of the past, with Jack Frye and Howard Hughes, the pilots built the airline to greatness. Bill Compton can inspire the re-creation of those great days again, and rejuvenate this great airline to its former standing as a pioneer and leader of the United States air transport industry.

|

|

|

Engines

|

BMW Rolls-Royce BR715 (18,500 lb) x 2

|

Length

|

124 feet

|

|

MGTOW

|

114,000 lb

|

Span

|

93 feet

|

|

Range

|

1,650 miles

|

Height

|

29 feet

|

|

|

|

Farewell Jo a Workhorse

On 30 September 2000, T. W.A. retired its last Boeing 727. The fleet of tri-jets had paid its dues. In addition to its extensive scheduled work, it had been on hand for specialized charters, for clients who included the St. Louis Rams football team (for whom one aircraft was specially painted); sixteen baseball teams; and one named Shepherd One, which took the Pope on tour. But its time had come, to be replaced by a more modern, more efficient aircraft.

Last of Another Fine Line

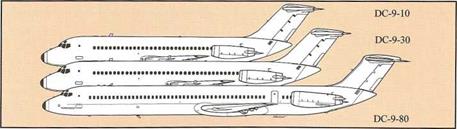

The McDonnell Douglas MD-80, the largest of the original DC-9 line, had supplemented the Boeing 727 for several years. It carried almost as many passengers (142 v. 145) but burned much less fuel (954 v. 1,214 gallons per hour). Now, to meet the demand for a smaller, even more fuel-efficient partner, to serve routes of lower traffic density, another fine aircraft was added to the T. W.A. fleet.

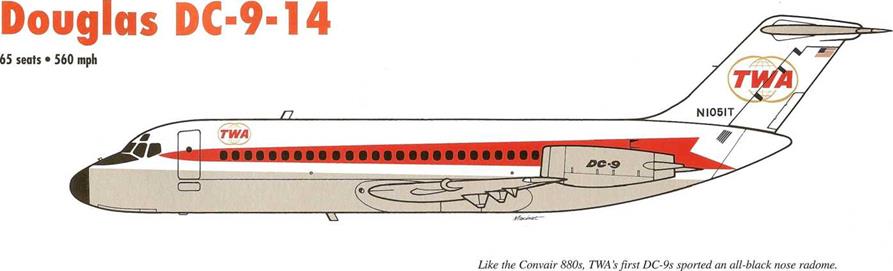

The Boeing 717 is the renamed ultimate development of Donald Douglas’s original twin – jet, the DC-9-10, which first flew on 25 February 1965. The 717’s first designation was the MB-95, and it first flew on 2 September 1998, by which time the McDonnell Douglas Corporation had been acquired by the Boeing Company, which promptly found a slot in its traditional numbering series. It was first ordered by Valujet (now AirTran) and T. W.A. ordered 50. The first one entered service on 2 March 2000, between St. Louis and Dallas/Fort Worth.

The Boeing 717 has the standard DC-9 fuselage cross-section, and is slightly longer than the DC-9-30, but with the MD-50 wing and an MD-87 extended vertical stabilizer. The flight deck is digitally equipped, with the new “glass cockpit.” Its BMW Rolls-Royce BR715 engines are more fuel efficient, have less exhaust emission, and are significantly quieter than any of the previous members of the famous Douglas twin-engined series. As indicated in the fleet list, deliveries will continue until the Summer of 2003.

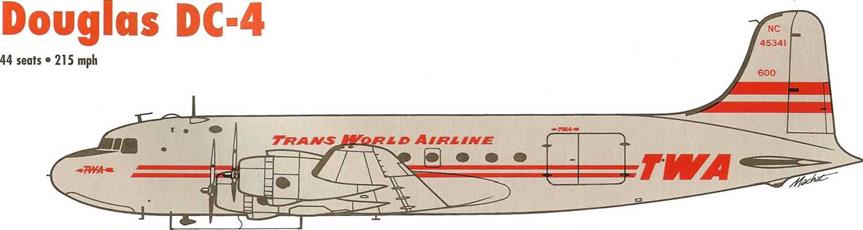

T. W.A. can thus claim to have been part of this great family of Douglas airliners, from the first (see page 77) to the last, with almost every sub-series in between.

|

|

Shortly thereafter, on 20 July, T. W.A. ordered 20 twin-jet, rear-engined Douglas DC-9s, once again taking the home-built product in preference to the British Aircraft Corporation’s BACOne-EIeven, This was the first second-generation rear-engined twin-jet to follow the Caravelle, and it had already made inroads into the American market. But T. W.A. chose the DC-9 and started service on 17 March 1966 (see page 77).

Shortly thereafter, on 20 July, T. W.A. ordered 20 twin-jet, rear-engined Douglas DC-9s, once again taking the home-built product in preference to the British Aircraft Corporation’s BACOne-EIeven, This was the first second-generation rear-engined twin-jet to follow the Caravelle, and it had already made inroads into the American market. But T. W.A. chose the DC-9 and started service on 17 March 1966 (see page 77).

A camaraderie emerged that survived into the retirement years. This has taken the form of former flight attendant groups, such as Clipped Wings and Silver Wings. They meet regularly and keep in touch through newsletters, chapter meetings, and annual conventions. Clipped Wings produced a handsome volume, Wings of Pride, honoring a great profession. The Clipped Wings maintain a ‘fashion archive’ of T. W.A. uniforms worn throughout the years and enjoy presenting fashion shows, in which members model their own uniforms from bygone days.

A camaraderie emerged that survived into the retirement years. This has taken the form of former flight attendant groups, such as Clipped Wings and Silver Wings. They meet regularly and keep in touch through newsletters, chapter meetings, and annual conventions. Clipped Wings produced a handsome volume, Wings of Pride, honoring a great profession. The Clipped Wings maintain a ‘fashion archive’ of T. W.A. uniforms worn throughout the years and enjoy presenting fashion shows, in which members model their own uniforms from bygone days.

Ray Dunn presides over a morning hour-long briefing in 1962 at the Mid Continent International Airport, where trouble-shooting was refined by long distance telephonic communication throughout the TWA system.

Ray Dunn presides over a morning hour-long briefing in 1962 at the Mid Continent International Airport, where trouble-shooting was refined by long distance telephonic communication throughout the TWA system.