Into the 21st Century

Picking up the Pieces

T. W. A. set about the task of recovery, after the departure of Carl Icahn. In July 1993, William Howard had been named chairman and C. E.O., but he resigned in January 1994, to be replaced by Donald F. Craib, Jr. Some sense of purpose returned to the airline when Jeffrey H. Erickson was elected president in April. He had airline credentials, having started as a Pan American engineer, moved on to various airlines, and had launched the low-fare new entrant, Reno Air, in July 1992. He took action to restore confidence. Service was started from St. Louis to some mid-west points, as well as to Sacramento and Ontario. International service was restored to Saudi Arabia, where T. W.A.’s tradition went back a long way, having served Dhahran, on the Gulf, from July 1946 to May 1971. Now the terminus was Riyadh, the handsome capital, which has one of the world’s most beautiful terminal buildings. But service to Geneva and Zurich was terminated, and the Los Angeles-Paris Polar route was suspended, as these routes were just not paying their way.

The employees responded, as best they could, supporting from their pay packets the $223,000 per month lease payments for a new McDonnell Douglas MD-83 (#9408) appropriately named Wings of Pride. Delivery was made at a proud ceremony on 2 September 1994.

But Pride is often accompanied by a Fall. By October, T. W.A. was asking its major creditors to “forgive” almost half of its $1.8 billion debt, in exchange for more equity. This would increase the creditors’ stake in the airline from 55% (the legacy of Carl Icahn) to 70%. But the creditors were wary, and in no hurry. T. W.A. was once again forced into a corner.

Chapter Eleven Again

When John Cahill was elected chairman of the board on 28 February 1995, the prospects were grim, and on 30 June, T. W.A. filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy for a second time. However, there was a silver lining. In August, the three unions agreed to $130 million per year savings in wages and through increased productivity, at the same time reducing their ownership in the airline from 45% to 30%. The wary creditors accepted the 70% shareholding in exchange for debt.

In February 1996, T. W.A. ordered 20 Boeing 757-200s, with options for another 10. They were to replace the Lockheed TriStars, which were becoming costly to maintain. The 757s had a common cockpit with the 767, another cost saving; and in the long term it was the beginning of a program of reducing the average age of the fleet.

Perry Flint, of Air Transport World, was encouraging: “Somehow, T. W.A. survived its near-death experiences and the long-awaited obituary never appeared… is in better shape than at any time in this decade.. . (it) has a sense of purpose, rising pride in its product, and a confidence bom of having survived the worst that man and nature could throw at it.”

The Cruel Hand of Fate

On 17 July 1996, Flight TW800, a Boeing 747, disintegrated at the eastern end of Long Island, still on its initial climb out of New York’s JFK Airport. The direct cause was the explosion of the center fuel tank, but the cause is not known for certain. After four years of research, the official explanation was that it might have been an inducted spark into low-tension wiring, but most aviation folk are skeptical.

In an interesting, though unfortunate, parallel, this disaster, which killed more than 200 people, occurred just when T. W.A.’s financial situation was improving; and was a tragic repetition of a similar situation in December 1988, when the Pan American 747 exploded at Lockerbie, Scotland, just when the airline was striving to recover its North Atlantic market share. In both cases, the effect on the travelling public’s perception was detrimental — to put it mildly.

Firm Hands at the Wheel

T. W.A. was undeterred. On 17 September it announced the acquisition of ten more MD-83s, making 15 in the fleet. Gerald Gitner became chairman and C. E.O., while Erickson retired. Gitner was joined, on 3 December 1997, by William (Bill) Compton, who became president and chief operating officer (C. O.O.). Bill was a veteran T. W.A. pilot, who had joined T. W.A. at the age of 21, had risen in the ranks to become the elected leader of the pilots’ union, ALPA, and had the distinction of having been furloughed three times. During T. W.A.’s turbulent years, the term distinction was indeed the operative word.

In 1995, the debt to Carl Icahn had been re-structured. T. W.A. agreed to pay off the debt by making available to Carl’s airline ticket agency the right to sell tickets. The arrangement was for eight years, and the airline will be relieved of the obligation in September 2003.

The Largest Order

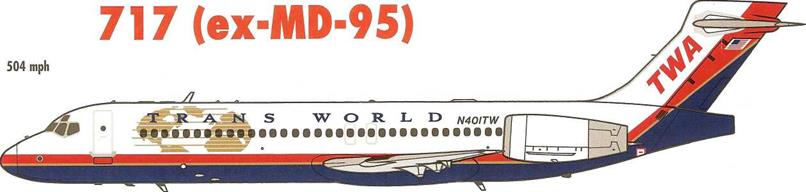

The year 1998 ended on a high note. In December, T. W.A. announced orders for 100 new airliners. The order comprised 50 111-seat Boeing 717-200s (formerly McDonnell Douglas

MD-95s) and 50 106-seat Airbus A318s. Both aircraft are at the lower stratum of jet airliner size, and will fulfill the need for the sparser traffic-generating routes, with considerably lower operating costs that those of the aircraft they replace. This was the first order for the A318 and one of the first for the 717, and T. W.A. was able to negotiate a good price, taking advantage of what is known in the industry as “launch economics.” T. W.A. also indicated its intention to order 25 more Airbuses, unspecified variants of the Airbus A320 family.

This acquisition — valued at around $4 billion, the largest in T. W.A.’s history — was marred slightly by the beginning of a “sick-out” by some flight attendants on Christmas Eve. They made a rapid recovery on the day after Christmas, by order of Judge Nina Gershon. But confidence was maintained in financial quarters in March 1999, when Boeing arranged $2.4 billion of financing to protect 82 unfilled T. W.A. orders, including the 717s.

Historical Precedent

In May 1999, Bill Compton was appointed C. E.O. as well as holding the office of president. Many years had passed since T. W.A. had been directed from the top from someone who had risen from within the ranks. As a pilot — he still kept his license current by taking the left-hand seat on an MD-83 flight deck from time to time — he enjoyed the respect of the flying crews. In his first months as CEO, he oversaw agreement on new contracts for all union-represented employees with pay increases that were mirrored by wage boosts provided to non-union workers as well. Although T. W.A. still trailed other major airlines’ pay scales, it marked the first time in 15 years that T. W.A. workers had been given more pay rather than more concessions in a contract.

Trans World Airlines moves into the twenty-first century in good spirits, even though its finances are still precarious. It has the best on-time record in the industry (“worst to first in three years.”) Its once old, almost time-expired, fleet (one Boeing 747 was retired with more than 101,000 hours flying time behind it) is being replaced by new aircraft, and the average fleet age is rapidly decreasing. Its loyal staff have increased productivity and the management is keeping its head. In the year 2000, T. W.A. celebrates its 75th anniversary, with a pilot up front, just as, in the great years of the past, with Jack Frye and Howard Hughes, the pilots built the airline to greatness. Bill Compton can inspire the re-creation of those great days again, and rejuvenate this great airline to its former standing as a pioneer and leader of the United States air transport industry.

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||