PROGRESS M-61

Progress M-61 was launched from Baikonur at 13:33, August 2, 2007. After a standard rendezvous it docked automatically to Pirs’ nadir at 14: 40, August 5. The new Progress delivered a 2,569 kg cargo of propellants, water, oxygen, dry cargo, and personal items for the crew.

|

STS-118 DELIVERS “STUBBY”

|

STS-118 was Endeavour’s first flight in 4.5 years, during which the orbiter had undergone extensive modifications. With Endeavour on the launchpad in mid-July, NASA engineers displayed the usual “Go Endeavour’’ banner on the gate across the bottom of the crawlerway ramp, only the banner in question read “Go Endeavor,’’ the American spelling, while the Shuttle’s name is spelt the British way, having been named after the Royal Navy ship sailed by the British 18th-century explorer Captain James Cook. When the mistake was pointed out the banner was quickly removed and replaced by one with the correct spelling. It was a small thing with no effect on the launch preparations.

In the run-up to launch, much of the media coverage centred on Barbara Morgan, who had first been selected to fly the Shuttle into space in the early 1980s, when she was one of two high school teachers selected for President Ronald Reagan’s “Teacher in Space’’ programme. Ultimately, Morgan was selected as the back-up and she watched the launch of STS-51L from the roof of the VAB, at KSC, on January 28, 1986. From there she saw the Shuttle explode, just 75 seconds into its flight, killing Commander Richard Scobee, Pilot Mike Smith, Mission Specialists Judy Resnik, Ellison Onizuka, Ronald McNair, Payload Specialist Gregory Jarvis, and high school teacher Christa McAuliffe. Morgan had returned to teaching before applying to become a full-time professional astronaut. She was subsequently selected as part of the 1998 astronaut group. When President George W. Bush announced his Educator Astronaut Project, a plan to select one professional educator in each subsequent annual astronaut group, Morgan was named as the first Educator Astronaut in 2002 and began training as a Mission Specialist on STS-118. The original Teacher in Space and the Educator Astronaut Project had the same objective, to encourage America’s schoolchildren and college population to study mathematics, science, and engineering and to be generally inspired by the act of spaceflight itself. In her pre-launch interview Morgan remarked:

“I’m really excited about going up and doing our jobs and doing them well. I’m excited about experiencing the whole spaceflight, seeing Earth from space for the very first time and experiencing weightlessness and what that’s all about. I’m excited about seeing what it’s like living and working onboard the International Space Station.’’

To some journalists it seemed appropriate that Christa McAuliffe’s back-up should make the first Educator Astronaut flight on Endeavour, the orbiter that had been constructed to replace Challenger. On the subject of STS-51L, Morgan said, “The legacy of Christa and the Challenger crew is open-ended. I see this as a continuation. The great thing about it is that people will be thinking about Challenger and thinking about all the hard work lots of folks over many years have done to continue their mission.’’

NASA Administrator Michael Griffin was more succinct, stating, “Every time we fly I know that we can lose a crew. That occupies a large portion of my thoughts. Unless we’re going to get out of the manned spaceflight business, that thought is going to be with me every time we fly.’’

Morgan’s Educator Astronaut tasks were secondary to her other mission tasks; she would operate Endeavour’s RMS to provide images of the installation of the S-5 ITS, which would be manoeuvred into place by the SSRMS, mounted on the MT. The S-5 was a spacer, used to provide sufficient room to allow the S-6 SAWs to function correctly when they were installed. A similar unit, the P-5 ITS, was already in place. The S-5 and P-5 spacers, which were each the size of a compact car, also included all of the plumbing and electronics needed to ensure that the S-6 and P-6 ITS elements could function as part of the overall ISS power and cooling system. It would require three EVAs to complete all of the necessary connections to make the S-5 ITS an integral part of the ITS. Anderson explained:

“We add this little spacer, S-5, which we call ‘Stubby’—P-5 was ‘Puny,’ so you had ‘Puny’ on the left and ‘Stubby’ on the right—and you add that piece so that when STS-120 comes to bring me home… we’re going to take the P-6 module that’s been sitting up on top of the station since its arrival, they’re going to take that off, move it outboard on the P[ort] side and stick it on. So now we’ll have three sets of solar arrays…’’

Lead Shuttle Flight Director Matt Abbott described the flight in the following terms, ‘‘This mission has lots of angles. There’s a little bit of assembly, there’s some

re-supply, there’s some repairs, and there’s some high-visibility education and public affairs events. It’s a little bit of everything.”

As well as the S-5 ITS, STS-118 would also carry the last SpaceHab logistics module to ISS. SpaceHab was carried rather than an MPLM because the S-5 ITS left insufficient room in the orbiter’s payload bay for the latter. The crew would also replace the CMG, in the Z-1 Truss, that had failed in October 2006, using procedures similar to those employed by the STS-114 crew when they replaced a malfunctioning CMG in 2005. In its basic form, STS-118 was a standard 11-day flight to ISS. However, Endeavour would be the first orbiter to carry the Station-Shuttle Power Transfer System (SSPTS). As the name suggested, the SSPTS allowed electrical power generated by the station’s ITS SAWs to be transferred to a docked Shuttle orbiter, powering its systems. If the SSPTS worked correctly, flight managers would have the potential to extend the stay on ISS by up to 3 days, and even to add a fourth EVA to the flight. Future Shuttle flights might be extended by up to 6 days by using the SSPTS.

During the countdown, a faulty valve caused a pressure leak in Endeavour’s crew compartment. It was replaced by a similar valve, removed from Atlantis. The leaking valve, together with thunder storms that caused delays in the pre-launch work on the launchpad, led to the August 7, 2007 launch being delayed by 24 hours on August 3. The delay gave NASA the opportunity to launch the Phoenix probe, which only had a 3-week launch window if it was going to reach its proposed landing site on Mars.

STS-118 finally lifted off at 18: 36, August 8,2007. Representatives of some of the STS-51L crew members’ families were at KSC to see the launch. Ironically, given the media’s concentration on Morgan, members of the McAuliffe family were not among them. As Endeavour left the launchpad, ISS was over the Atlantic Ocean, southeast of Nova Scotia. Onboard cameras showed that nine pieces of foam separated from the ET and at least three appeared to strike Endeavour. The first was seen at T + 24 seconds, and looked as though it struck the body flap at the orbiter’s rear. The second piece was seen at T + 58 seconds, and resulted in a spray and decolourisation on the right wing. The third and subsequent pieces departed from the ET after STS-118 was above the sensible atmosphere and were therefore not thought to have had sufficient energy to damage the orbiter. A few minutes later, Endeavour was in orbit. In Houston, astronaut Rob Narvis announced, “… Class is in session.’’ Approximately 90 minutes after launch, a fragment of a Delta launch vehicle launched in 1975 passed within 2.4 km of Endeavour. Flight Day 1 ended at 00: 36, as the crew began their first sleep period in orbit.

Day 2 began at 08 : 37. During the first full day in space, Hobaugh, Caldwell, Mastracchio, and Morgan used the RMS to lift the OBSS from the opposite side of the payload bay at 11: 20, and spent the next 6 hours using its cameras and laser sensors to view the orbiter’s TPS. Elsewhere, the crew checked their rendezvous equipment, installed the docking system centreline camera, and extended Endeavour’s docking ring. During a television broadcast, Morgan told the audience, “Hey, its great being up here. We’ve been working really hard, but it’s a really good fun kind of work.’’ The day ended at 23: 36.

|

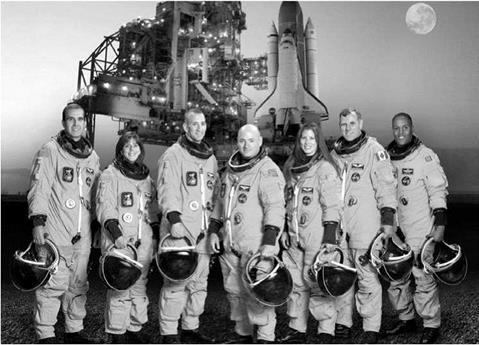

Figure 95. STS-118 crew (L to R): Richard A. Mastracchio, Barbara R. Morgan, Charles O. Hobaugh, Scott J. Kelly, Tracy E. Caldwell, Dafydd R. Williams, Alvin Drew, Jr. |

|

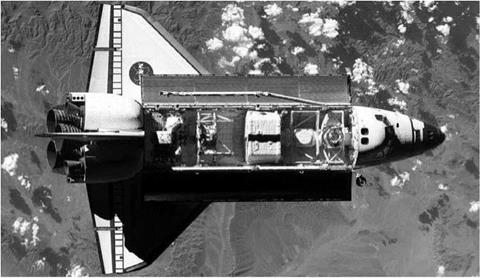

Figure 96. STS-118 approaches ISS, the payload bay holds External Stowage Platform 3, the S – 5 Integrated Truss Structure and a SpaceHab module full of supplies for the station. |

August 10 began at 07: 36. After eating their breakfast the crew commenced preparations for rendezvous and docking with ISS. Final rendezvous manoeuvres began at 11: 14, when Kelly performed the Terminal Initiation burn. He told the Expedition-15 crew, “We’re about 30,000 feet away. You’re looking very good.” Anderson replied, “All right, man, keep up the good work. We’re waiting for you.’’

Closing to within 200 m of the station, Kelly manoeuvred Endeavour through its r-bar pitch manoeuvre, allowing Yurchikhin and Kotov to expose a series of high – definition digital images of the orbiter’s underside, which were down-linked to Houston. When experts on the ground examined the photographs they identified a 7.5 cm x 7.5 cm gouge in the underside of Endeavour’s starboard wing, close to the main landing gear door. When he was told of the damage, Kelly replied, “Thanks for the update.’’ It was decided to carry out an OBSS inspection of the area with the orbiter docked to ISS.

Docking to PMA-2 on Destiny’s ram occurred at 14: 02. The hatches between the two spacecraft were opened at 16: 04, and Endeavour’s crew entered Destiny, where they were greeted by Yurchikhin, Kotov, and Anderson. After a short ceremony, the new visitors received the usual safety brief from their hosts. At 16: 17 the crew activated the SSPTS and electrical power produced by the ISS’ SAWs flowed into a docked Shuttle for the first time. One of the first activities following docking was Mastracchio using the RMS to lift the S-5 ITS out of the payload bay and hand it over to the SSRMS, operated by Hobaugh and Anderson. The S-5 ITS was then left on the end of the SSRMS overnight to acclimatise to the space environment. Work began at 18: 00 to unload the first of the supplies from Endeavour’s SpaceHab module. Meanwhile, Mastracchio and Williams spent the night camped out in Quest with the air pressure reduced, in preparation for their first EVA the following day.

In Houston, engineers had inspected the video from the various cameras mounted on the Shuttle during lift-off. They showed that the gouge on the underside of the right wing had been caused by a grapefruit-sized piece of foam that had shed from the ET and struck a bracket on the fuel line at the rear of the tank as it fell away. The impact had changed its course, leading to the impact with the underside of the right wing. Although the planned OBSS inspection would go ahead, NASA now felt sure that Endeavour could re-enter Earth’s atmosphere without the need for an EVA to repair the TPS. Mission Manager John Shannon stated, “It’s a little bit of a concern to us because this seems to be something that has happened frequently.’’

During the night, Endeavour’s crew was woken up by an audible alarm, which had activated because the use of the SSPTS had allowed one of the Shuttle’s fuel cells to cool down more than on previous flights. The alarm’s tolerance level was adjusted to take the lower temperature into account.

Endeavour’s crew was officially woken up at 07: 38; they then ate their breakfast. After supplying electrical power to Endeavour throughout the night, the SSPTS was powered off prior to the EVA, which began at 12: 28, August 11, after Hobaugh had used the SSRMS to position the S-5 ITS at the exposed end of the S-4 ITS. Mastracchio and Williams left Quest and made their way to the area, where they gave verbal instructions to assist in the final positioning of the new ITS element. The tolerances between the S-5 ITS and other parts of the station were at times only a few centimetres, and with no cameras in the area, verbal instructions were vital. They then set about bolting the new ITS in place and completing the electrical and plumbing connections between the S4 and S-5 ITS. The S-5 ITS was considered to be officially “in place” at 14:26.

At 15: 52, while the EVA was underway, the primary American Command & Control computer, in Destiny, shut down without warning. The back-up computer immediately assumed the primary role and the third, stand-by computer assumed the back-up role, exactly as they had been programmed to do. The EVA was not affected and ISS was never in danger. Controllers in Houston began troubleshooting the problem.

After installing the S-5 ITS, Mastracchio and Williams made their way to the P-6 ITS, where they retracted the forward radiator. This was the final task to prepare the P-6 ITS for its removal from the Z-1 Truss and relocation to the exposed end of the P-5 ITS. That task would be completed by the crew of STS-120, after they had temporarily installed Harmony on Unity. The STS-118 EVA ended at 18: 45, after 6 hours 17 minutes. The SSPTS was powered on after the EVA was complete and began supplying power to Endeavour once more.

August 12 began on Endeavour at 07 : 07 and was the day that the Shuttle crew inspected the damage caused to their vehicle by foam and ice shedding from the ET during lift-off. Hobaugh and Anderson used the SSRMS to lift the OBSS from its storage position, and handed it off to Endeavour’s own RMS at 09: 45. Kelly, Caldwell, and Morgan then spent 3 hours operating the RMS to view five damaged areas of TPS on the underside of Endeavour using the cameras and laser instruments on the OBSS to form a three-dimensional image of the damaged areas. Four of the five areas inspected offered no threat to re-entry. The fifth and by far the largest area was the 7.5 cm x 7.5 cm gouge seen earlier in the flight. Engineers in Houston would reconstruct the large gouge and test it under simulated re-entry heating temperatures. In the event that the gouge was found to threaten Endeavour during re-entry, the crew had three options for repair, all of which would involve an EVA:

• Apply a thermal paint to the exposed surface of the gouge.

• Install a cover plate of TPS material.

• Fill the gouge with a caulking material.

Throughout the day, Williams, Hobaugh, Mastricchio, and Drew spent their time transferring equipment and logistics from SpaceHab to ISS. In Houston, flight managers reviewed the operation of the SSPTS and extended the flight of STS-118, pushing Endeavour’s undocking from the station back to August 20, with landing 2 days later. The extra time would be used for a fourth EVA, by Williams and Anderson, to install a berth on the exterior of ISS to hold the OBSS. Just after 21: 00, Mastracchio and Williams began their second overnight camp-out in Quest, in preparation for their second EVA.

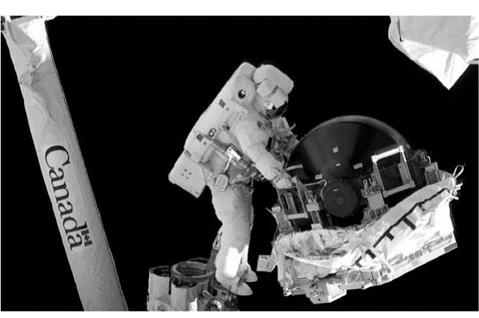

That EVA began at 11 : 32, August 13, when the two astronauts left Quest and made their way to the Z-1 Truss, using the SSRMS operated by Hobaugh and Anderson. Once in location they removed the CMG that had failed in October 2006. The failed CMG was carried to a temporary stowage location, while they installed a new CMG, which had been carried into orbit in Endeavour’s payload bay, mounted on External Stowage Platform 3. With the EVA progressing well, Caldwell told Mastracchio and Williams, “You guys rock.’’ The final task was to move the failed CMG from its temporary location to External Stowage Platform 2 on the exterior of ISS, where they secured it to await recovery and return to Earth on a later Shuttle flight. The EVA ended at 18: 00, after 6 hours 28 minutes.

Throughout the EVA, Drew continued to transfer equipment from SpaceHab to ISS, a task that other crew members assisted with once the EVA was complete. In Zvezda, Yurchikhin and Kotov continued searching Zvezda for the cause of the computer failure that had occurred during the visit of STS-117. On removing some wall panels in the Russian module they discovered that condensation had collected behind them.

In Houston, mission managers announced that the OBSS survey had shown that the largest gouge on Endeavour’s underside passed right through the TPS tiles and had exposed the felt that was laid between the TPS tiles and the orbiter’s aluminium skin. Discussions were underway as to whether or not the crew should make a repair before leaving ISS, but Mission Manager John Shannon told a press conference, “This is not a catastrophic loss-of-orbiter case at all. This is a case where you want to do the prudent thing for the vehicle.’’ He added, “we have really prepared for exactly this case, since Columbia [STS-107]. We have spent a lot of money and a lot of people’s efforts to be ready to handle exactly this case.’’

Shannon explained that it might be better to add a complicated TPS repair EVA to the flight, rather than risk more serious damage being caused during re-entry that would require long repairs and throw the already tight launch schedule into further disarray. He also assured journalists that mission managers had ruled out the second repair option, screwing a pre-prepared plate of TPS material over the damage, as the damage did not warrant such drastic measures. The choice now was between the thermal protection paint and the caulking material. On the subject of what this foam – shedding event meant to the launch schedule, Shannon would not be drawn, saying only, “We have a lot of discussion to have before we fly the next [External] Tank.’’

Endeavour’s crew began their sleep period at 22: 06.

Two events were marked during the August 14 working day. Endeavour’s crew were woken up at 06: 07, by a recording of Caldwell’s nieces and nephews singing, “Happy Birthday, dear Tracy,’’ to mark the astronaut’s birthday. Also, at 11: 15, Zarya, the first American-financed ISS module to be launched, completed its 50,000th orbit.

Caldwell and Morgan used Endeavour’s RMS to lift External Stowage Platform 3 out of the Shuttle’s payload bay, and hand it over to the SSRMS. Hobaugh and Anderson then moved it into position. The 4 m x 2 m platform, which held a second, spare CMG, a nitrogen tank assembly, and a battery charger/discharger unit, was attached to the P-3 ITS at 12: 18. The previous two ESPs had been installed on Destiny and Quest by astronauts making EVAs.

During the day, Kelly, Caldwell, and Morgan were interviewed by news organisations, and Kelly answered a question on the damage sustained by Endeavour during launch, saying, “My understanding is that the tile damage is not an issue for the safety of the crew. We may still choose to repair, but I’m not concerned with our safety.”

Morgan then joined Anderson, Williams, and Drew in answering questions from children at the Discovery Centre in Boise, Idaho. One child asked Morgan how being an astronaut compared with being a teacher. She replied:

“Astronauts and teachers actually do the same thing, we explore, we discover and we share. And the great thing about being a teacher is you get to do it with students, and the great thing about being an astronaut is you get to do it in space and those are absolutely wonderful jobs.’’

The video conference continued with the students asking questions on a wide range of subjects and receiving answers from the astronauts on Endeavour. Asked about what it felt like to fly into space, Williams replied:

“As soon as the engines stop, you float forward in your seat, your arms rise up, and it’s an incredible sense of freedom. The first thing we like to do is go up to the window and look at the Earth. It’s an amazing sight.’’

On the ground, mission managers were still awaiting heating tests before deciding whether or not to repair the gouge in Endeavour’s underside. They continually made it clear during the day’s press conferences that any repairs undertaken would be to prevent prolonged repairs after flight and were not a matter of preventing the loss of Endeavour during re-entry. Mastracchio and Anderson spent the day preparing for their third EVA, the following day. They spent the night “camped out’’ in Quest. The crew’s day ended at 22: 06.

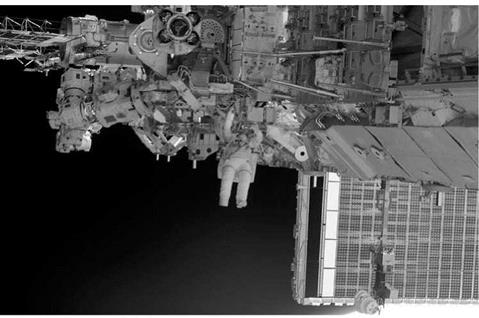

August 15’s work day began at 06: 07. Mastracchio and Anderson left Quest at 10: 38 to begin EVA-3. The two men worked together to relocate an S-band Antenna Sub-Assembly from the P-6 ITS to the P-1 ITS. They also installed a new transponder on the P-1 ITS, before removing the transponder on the P-1 ITS. Both men watched while Hobaugh and Kotov used the SSRMS to relocate the two CETA carts from the track on the port side of the MBS to its starboard side. In so doing, they cleared the track to the port side for the MBS to complete the transfer of the P-6 ITS, from the Z-1 Truss to the outer edge of the P-5 ITS, during the flight of STS-120. Throughout the movement of the CETA carts, Morgan used the cameras on Endeavour’s RMS to provide live images of what was happening.

At 14: 54, Mastracchio carried out one of the new periodic checks of his EMU gloves and discovered a cut in the thumb of his left glove that had passed through the outer two layers of the glove’s five layers of construction. The cut did not puncture the gas bladder, there was no leak, and Mastracchio was in no danger. Even so, he was instructed to return to Quest and return his Extravehicular Mobility Unit to the electrical power supply inside the airlock. In Houston, NASA spokesman Kyle Herring told a press conference, “The suit is perfectly fine. This is just a precaution.’’ Anderson completed the final task before returning to Quest at 16: 05, after 5 hours

|

Figure 97. STS-188: Canadian astronaut Dave Williams deploys a new Control Moment Gyroscope for installation in the Z-1 Truss. The old, failed CMG was temporarily stored on the exterior of the station. Williams is standing in a foot restraint held by the SSRMS. |

|

Figure 98. STS-118: Astronaut Richard Mastracchio at work on the Integrated Truss Structure during the flight’s third EVA. |

28 minutes. Plans to recover the MISSE-3 and MISSE-4 experiments were delayed until a later EVA.

Inside ISS, the remainder of the two crews spent the rest of the day on the transfer of equipment from SpaceHab to the station, which was half-complete. In Houston, mission managers delayed the fourth EVA from August 17 to August 18, but had not yet decided if it would be devoted to repairing Endeavour’s underside or to “get-ahead” tasks. Either way, on August 17 the crew would perform preparations for a repair, until managers told them that it was not required. If the repair went ahead, Mastracchio and Williams would ride on the end of the OBSS, which would be held in the end-effector of Endeavour’s RMS. They would be moved to the underside of the orbiter, where they would apply heat-resistant black paint to the gouge in the tiles then they would apply the caulking material to the gouge.

At 08: 06, August 16, Morgan and Drew spent time talking to students at the Challenger Centre for Space Science Education, Alexandria, Virginia. The centre had been set up by the families of the STS-51L crew. June Scobee-Rogers, the wife of STS-51L Commander Richard Scobee at the time of the STS-51L flight, was there to oversee the session. She began the session by greeting Morgan, “Barbara, we have been standing by, waiting for your signals from space for twenty-one years…’’ The questions that followed were many and varied. One student asked Morgan if she had had any special teachers in her own life. She replied that the seven people on STS-51L were mentors, “… that have meant more than anything to me. They were my teachers and I believe they are teaching us today, still.’’ As the broadcast ended, Morgan held an STS-51L mission patch up to the camera. The question-and-answer session was followed by interviews with a number of television and radio stations. Later in the day, Morgan also answered questions from the education district where she had been a high school teacher, during an amateur radio session.

The two crews spent most of the day transferring equipment between the two spacecraft, while Mastracchio, Williams, and Drew spent their time preparing for the fourth EVA and the repairs that they might have to make to Endeavour’s TPS. Just before the crew signed off for the day, Houston told them that the Mission Management Team (MMT) had decided that they would not carry out a repair to Endeavour’s underside. On receiving the news, Kelly replied, “Pass along our thanks for all the hard work the MMT and everyone down there is doing to support our flight.’’

In Houston, John Shannon told a press conference that the decision, “… was not unanimous, but pretty overwhelming.’’

The fourth EVA would now be dedicated to installing two antennae and a berth to hold the OBSS on the exterior of ISS between Shuttle flights. They would also recover the two MISSE trays that they had not recovered during the previous EVA. The day ended with both crews being given some off-duty time.

August 17 was another quiet day, with Mastracchio, Williams, and Drew preparing for the EVA now planned for the following day. The majority of the day was spent transferring equipment between the two spacecraft and talking with reporters in Houston and the Canadian Space Agency Headquarters in Montreal. Mission managers also had a new problem to consider, Hurricane Dean was approaching Houston, where the Shuttle control room was located. Plans were made to shorten the fourth EVA and even to undock a day early if the hurricane threatened the control centre. Mastracchio and Williams spent the night “camped out” in Quest when the crew began their sleep period at 23: 06.

The new day, August 18, began with a wake-up call at 05: 03. The crew were informed that due to the threat offered to Houston by the approaching hurricane the planned 6.5-hour EVA had been shortened by 2 hours. The shorter EVA would allow for the hatches between Destiny and Endeavour to be closed at the end of the day, preserving the option to undock one day earlier than planned. If required, mission control would move to a back-up facility at KSC, in Florida.

The final EVA began at 09: 17. Williams and Anderson installed the External Wireless Instrumentation System antenna, part of a system to measure stresses in the ISS structure. Next, they installed a stand for the OBSS, before recovering the two MISSE packages deferred from their previous EVA. Plans to secure micro-meteoroid shielding on Zvezda and Zarya and moving an external toolbox had been removed from the plan to facilitate the shorter EVA. During the EVA, ISS passed directly over Hurricane Dean, as it travelled across the Caribbean. Williams remarked, “Wow! Man, can’t miss that.” Anderson added, “Holy smoke, that’s impressive!” Both men returned to Quest at 14: 19, after an EVA lasting 5 hours 2 minutes.

Questioned during the crew’s joint press conference with the Expedition-15 crew about NASA’s decision not to repair Endeavour’s TPS, Kelly told journalists:

“I think it was absolutely the right decision to forego the repair… I think they took the appropriate amount of time to come to that conclusion.’’

He added,

“We have had Shuttles land with worse damage than this. We gave this a very thorough look; there will be no extra concern in my mind due to this damage.’’

Talking about the proposed repair, Mastracchio said:

“We were not looking forward to doing it, only because there was a lot of risk involved and a lot of long hard hours involved getting it all prepared… We felt comfortable we could go and accomplish it.’’

Williams had the final say:

“We [NASA] do not take chances; we manage risk. We are in the business of mitigating risk, and that is a data-driven process. To analyse all the appropriate data took time. They made the right decision. Going beneath the belly of the orbiter is something that has its own risk.’’

By 17: 10, the two crews had completed their goodbyes, during which Yurchikhin and Kelly embraced before the Russian told his American colleague, “Have a good

|

Figure 99. STS-118: the decision was made not to repair this tile damage on Endeavour’s underside. The damage to the orbiter’s heat protection system had no effect on re-entry, and Endeavour was recovered successfully.

Figure 99. STS-118: the decision was made not to repair this tile damage on Endeavour’s underside. The damage to the orbiter’s heat protection system had no effect on re-entry, and Endeavour was recovered successfully.

trip back to Earth.” Kelly led his crew back to Endeavour. The hatches between the two spacecraft were sealed and both crews settled down to their respective sleep periods.

Endeavour’s wake-up call came at 04: 37, August 19. After final checks, Endeavour undocked at 07:56 and backed away from Destiny’s ram. As the two spacecraft separated, Yurchikhin rang the ship’s bell on the station and remarked, “Endeavour departed.’’ Anderson added, “Thanks for everything Scott, and Endeavour crew, Godspeed.’’ Kelly replied, “We couldn’t have gotten everything accomplished without you guys. We look forward to seeing you back on planet Earth.’’

After a partial fly-around of ISS, the Shuttle was manoeuvred clear at 08:23. Following a second burn, at 09: 30, the crew used the RMS to lift the OBSS and use it to inspect Endeavour’s nosecap and the leading edges of both wings. They berthed the OBS back along the payload bay door hingeline at 14: 37. At 16: 35 the crew began four hours of free time in advance of their sleep period, beginning at 20: 36.

The last full day in space began at 04: 37, and the crew spent the day stowing their equipment prior to re-entry. Kelly, Hobaugh, and Mastracchio tested Endeavour’s thrusters and aerodynamic surfaces. Kelly, Morgan, and Williams took time to talk to schoolchildren in Canada, before closing out the SpaceHab module. The day ended at 20: 36.

Overnight, Hurricane Dean had hit land in Jamaica, in the process losing most of its power. It was downgraded from a Category 5 hurricane to a Category 1 tropical storm. Endeavour’s crew were woken up at 04: 36, August 21, and at 07: 26 began their final preparations for re-entry. The payload bay doors were closed at 08 : 45 and retrofire occurred at 11 : 25, resulting in a landing at KSC on the first of two opportunities that day. Kelly landed his spacecraft in Florida at 12: 33, after a flight lasting 13 days 17 hours 56 minutes. As Endeavour rolled out to wheel-stop, Capcom in Houston told the crew, “Welcome home. You’ve given ‘Higher Education’ a new meaning.’’

After the toxic fuels had been pumped from the spacecraft the crew were allowed to leave. On reaching the ground Kelly walked underneath Endeavour to look at the gouge in the TPS. He later described it as, ‘‘Somewhat underwhelming… it looked rather small.’’ Small or not, that one gouge had been the subject of some 4,000 hours of computer time and NASA Administrator Michael Griffin praised the engineers who had carried out those studies. He later reminded journalists at a press conference, ‘‘This is very much an experimental vehicle. Anyone who doesn’t believe that just doesn’t get it.’’

As to the cause of the gouge, NASA engineers believed that ice had formed on the ET, causing the foam to break away from one of the brackets holding the fuel line. That foam had then struck a second bracket and changed direction, striking the TPS on the underside of the orbiter. The bracket had already been redesigned to minimise foam loss, but tanks with the new brackets were not scheduled to come on-line until spring 2008, with the flight of STS-124. In the meantime, engineers were considering removing some of the foam from the bracket on the ETs of the three Shuttle flights before STS-124.

Predictably, throughout the flight of STS-118 much of the media coverage had concentrated on Barbara Morgan. There had been endless words written and spoken about her role as the back-up Teacher in Space for STS-51L, and how “Challenger exploded in January 1986, killing high school teacher Christa McAuliffe and six other crew members.” Regretfully, 21 years after the event, most of the journalists had seemed unable to name the “six other crew members”, or thought it was unnecessary to do so in their reports.