RETURN TO THREE EXPEDITION CREW MEMBERS

Following Discovery’s departure, the extended Expedition-13 crew settled down to work. Williams and Reiter installed the ESA experiment rack, which had been delivered by Discovery, in Destiny. They activated the Minus Eighty-degree Laboratory Freezer for ISS (MELFI), which Discovery had delivered and had been set up in Destiny. The freezer was supplied by ESA and contained four compartments offering a total of 300 litres of storage capacity. It would be used to store biological samples

|

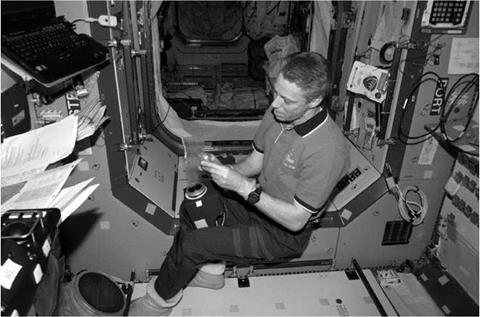

Figure 72. Expedition-13/14: European astronaut Thomas Reiter served with the Expedition – 13 and 14 crews. He is shown working with the SWAB experiment. |

prior to their return to Earth. On July 19, Vinogradov took three attempts to restart the Elektron unit and succeeded only after the bubbles had been driven out of the system. The crew also completed a check of the oxygen generation system that Discovery had carried to the station. When activated the new system would supplement the Elektron oxygen generator, in anticipation of future Expedition crews consisting of up to six people. Oxygen from the tanks in Progress M-56 was pumped into the station’s atmosphere on a daily basis throughout the latter half of July. The crew also began preparations for Williams and Reiter’s Stage EVA, by flushing the cooling loops in Quest and the American EMUs. On July 26, Russian controllers fired thrusters on Progress M-56 to raise the station’s orbital parameters and place it in the optimum position for the STS-115 launch, in August 2006. The Expedition-14 crew were due for launch in September 2006, on Soyuz TMA-9. The following day, Vinogradov removed the KURS system from Progress M-56 and stored it in Zarya. The last day of July was spent in maintenance of the American Common Cabin Air Assembly in Destiny. The new month began with Vinogradov transferring water from tanks in Progress M-56 to tanks in Progress M-57 and performed other maintenance tasks on the Life Support System in the Russian sector.

Williams and Reiter left Quest wearing American EMUs at 10: 04, August 3, 2006, for a Stage EVA that was planned to last 6 hours 20 minutes. Their first task was to install a Floating Potential Probe (FPP) on the S-1 ITS and extend its three sensor arms, to measure the electrical potential of the station as it orbited Earth. They quickly began to get ahead of their planned timeline for the EVA. Their second task was to install two suitcase-size Materials on International Space Station Experiment (MISSE) containers. The MISSE-3 container was installed on one of Quest’s high – pressure gas tanks while MISSE-4 was mounted on Quest’s outboard end. Following their individual installations the containers were opened to expose the material samples held inside to the space environment. Following these joint tasks, the two men set about individual tasks. Williams installed a controller for a Thermal Radiator Rotary Joint on the S-l ITS, before installing a starboard jumper and spool positioning device (SPD), also on the S-l ITS. Meanwhile, Reiter installed a Multiplexer/De-multiplexer, a computer, on the S-l ITS, replacing one that had failed in 2004, before examining a radiator beam valve module at a site where an SPD was already installed.

He then installed an additional SPD at that site. Finally, he installed an SPD on the port cooling line jumper. The jumpers were designed to assist the flow of ammonia in the radiators once the coolant was installed.

Williams then began the installation of a light to assist future EVA astronauts using the MBS to move along the assembled ITS. Following that work, he removed a malfunctioning GPS antenna. Elsewhere, Reiter tested an infrared camera designed to image the RCC thermal protection on the nose and leading edge of the wings of the Shuttle Orbiters. The camera was designed to show damage by highlighting the difference in temperature within the RCC sections. When he had completed these tasks he installed a vacuum system valve on the exterior of Destiny for use with future scientific experiments. That was the last of the planned EVA tasks, but, as the astronauts were so advanced on their timeline, Houston found a number of “get – ahead’’ tasks for them to perform. Williams relocated two articulated foot restraints in preparation for the EVAs planned for the visit of STS-115. He then photographed a scratch on the exterior of Quest. Reiter made his way to the exterior of PMA-1 to inspect and retrieve a ball-stack, used to hold equipment during EVAs. With no further tasks the two men returned to Quest and took photographs of each other. In Houston, astronaut Steve Bowen joked, “We will never let this happen again.. .Wait ’til you see next week’s schedule.’’ The pair re-entered Quest and closed the hatch at 16: 58, bringing their EVA to a close after just 5 hours 54 minutes. For the first time since 2003 a third Expedition crew member, Vinogradov, had been available to remain inside ISS and monitor systems, thereby doing away with the necessity to place the station’s systems into un-crewed mode during the EVA.

The day after the EVA, August 4, Reiter broke the ESA endurance record. When his time on Mir and ISS were combined he had broken the previous ESA combined record of 209 days 12 hours 25 minutes, set by French astronaut Jean-Pierre Haignere. Reiter’s position as the first International Partner on an ISS Expedition crew and the first International Partner to make an EVA from the station was seen by many in Europe as a forerunner of European activities following the launch of the Columbus laboratory module, then planned for September 2007. Reiter’s flight activities were being run from the Columbus Control Centre in Oberpfaffenhofen, near Munich, Germany. By the time he returned to Earth, at the end of his 5 months on ISS, Reiter would have spent more than a year in space. By that time he would have completed 23 experiments in 6 disciplines in the ESA “Astrolab” programme.

In the same week, the crew prepared for the arrival of STS-115. The Shuttle would deliver the P-3/P-4 ITS, and would see the resumption of construction on ISS. The Expedition-13 crew began packing up items that Atlantis would carry back to Earth. They also performed 2 days of routine maintenance. On August 10, controllers in Houston moved the SSRMS to allow its cameras to view markings on the exterior of ISS as part of the Space Vision System (SVS), which would be used to assist in the correct alignment of the new components that Atlantis would deliver to the station. The following day, Williams walked the SSRMS from the exterior of Destiny on to the recently repaired MT, and then used its cameras to view the exposed end of the P-1 ITS, where the new P-3/P-4 ITS would be mounted.

In the second half of August the Expedition-13 crew continued to pack items for return to Earth on Atlantis. The Carbon Dioxide Removal Assembly was tested in advance of the Shuttle’s arrival and the station’s orbit was raised by a burn of the Progress M-56’s thrusters, on August 23. The crew also continued their experiment programme, routine maintenance, and exercise regimes.

STS-115 was due for launch on August 27, but was delayed, ultimately until September 9. The crew on ISS used the extra time to complete their preparations for the Shuttle’s flight. They worked on cosmic ray studies that involved Williams spending a complete orbit in the prone position wearing a helmet with sensors to monitor his brain activity and visual perceptions. Vinogradov spent much of the time maintaining the Elektron unit.

|

STS-115 DELIVERS THE PORT-3/4 ITS

|

As July turned August 2006, the American press began to fill with stories of STS-115, Atlantis, and how its six-person crew would restart the construction of ISS. The Shuttle would deliver the combined port-3 and port-4 (P-3/P-4) ITS. The inward end of the P-3 ITS would be permanently attached to the exposed end of the P-1 ITS. The P-3 ITS contained a Solar Alpha Rotary Joint (SARJ), which would allow the three outer segments of the port ITS (P-4 and the P-5/P-6) to rotate, in order to keep their SAWs directed towards the Sun. The construction would require three EVAs from Quest.

STS-115 stood at Launch Complex 39 in late August. The weather on August 25 was abysmal, rain; low, dark clouds; and thunder. At one point lightning struck the conductor on the top of the launch structure tower, causing a spike in several electrical systems. When the weather had passed the launch was delayed for 24 hours, from August 27 to August 28, in order to carry out thorough systems checks in the wake of the lightning strike. Even as the checks were completed Hurricane Ernesto was in the Caribbean, approaching Cuba. If it continued on its present course and regained strength over the open sea it might strike KSC with storm winds in excess of speeds in which it was safe for the Shuttle to remain on the launchpad. Two parallel plans were put in place. First, work continued to prepare Atlantis for launch, if the winds abated. Second, work began in preparation to roll Atlantis back to a safe haven constructed in the VAB.

Further difficulties were placed on the launch by the lighting requirements of the cameras that would film the ET during launch and the requirement to jettison the ET on the daylight side of Earth. These requirements had been placed on the first two launches after the loss of STS-107 by the CAIB. Although the current launch window ran until September 13, NASA wanted to launch before September 7, rather than delay the launch of Soyuz TMA-9 carrying the Expedition-14 crew, planned for September 14. The Expedition-13 crew were due to return to Earth in Soyuz TMA-8 on September 24, and any delay in the launch of Soyuz TMA-9 would result in a night-time recovery for Soyuz TMA-8.

Programme manager Mike Suffrendi told the media, “This flight has to occur for the next flight to occur and then the next flight and the next flight… Even though we say we take them one at a time, this one is a key. This is clearly in the critical path for assembly.”

On August 30, NASA began the 12-hour-long roll-back of Atlantis to the VAB. Four hours later, Hurricane Ernesto had altered course, having lost much of its energy over Cuba. The decision was made to stop the roll-back and return Atlantis to the launchpad. Lift-off was rescheduled for September 8.

With the countdown proceeding, an electrical short circuit caused the failure of a coolant pump in one of four power generators in one of Atlantis’ three fuel cells. The problem was that the fuel cell might fail in flight, causing Atlantis to return to Earth early, without installing the P-3/P-4 ITS. Despite everything, NASA managers decided that the risk of failure was minimal and the launch preparations continued. The crew were suited up, transported out to the launchpad, and installed in the spacecraft. As the countdown continued, a new problem arose with one of four fuel cut-off sensors within the ET. The sensor was responsible for sensing the amount of propellant in the ET’s liquid hydrogen tank and ensuring the three Space Shuttle Main Engines shut down if the main computer failed. There were similar sensors in the liquid oxygen tank. Mission Rules dictated that all the sensors be working before the launch could go ahead. On this occasion flight managers decided that the launch could not continue. The launch attempt was scrubbed and the crew removed from the spacecraft.

The following day, September 9,2006, the whole procedure began again. Following a near perfect countdown, at 11: 15 Atlantis climbed into the blue Florida sky on her first flight since 2002. Although the launch events appeared to go well, review of the numerous video tapes showed that four or five small pieces of foam shed from the

ET. These events all occurred after Atlantis had left the thick lower atmosphere and, therefore, mission managers were sure that the foam did not have enough energy to cause major damage to the orbiter. All launch events passed off as planned and video cameras on the ET captured both the SRB and ET separation. Tanner and MacLean shot hand-held video and still images of the ET as it drifted away. Programme Manager Wayne Hale remarked, “The bottom line is we are looking at nits, nothing of remote consequence. Of course, we will inspect the entire heatshield with a fine – tooth comb.” As Atlantis lifted off, ISS was over the Atlantic Ocean, between Iceland and Greenland. The Expedition-13 crew watched the launch on a NASA television link. Once in orbit the crew prepared Atlantis for sustained spaceflight. On the ground, astronaut Mike Fincke told the media, “The logjam behind is huge… We have a very solid end date for the Space Shuttle, so each mission has to happen one after another in the sequence.”

On September 10, Jett and Ferguson began the manoeuvres that would result in rendezvous with ISS. Meanwhile, Ferguson, Burbank, and MacLean used the RMS to lift the OBSS and view Atlantis’ right and left-wing leading edges and the carbon – carbon nosecone, before returning the OBSS to its stowed position. Initial reviews of the images obtained showed no damage to Atlantis from the foam shed from the ET during launch. In one place on Atlantis’ underside a shim and a tile spacer were seen protruding out from between the TPS tiles. Tanner and Stefanyshyn-Piper prepared the EMUs and EVA tools they would transfer to ISS for the three planned EVAs. On the station, Vinogradov and Williams pressurised PMA-2 in preparation for the Shuttle’s arrival.

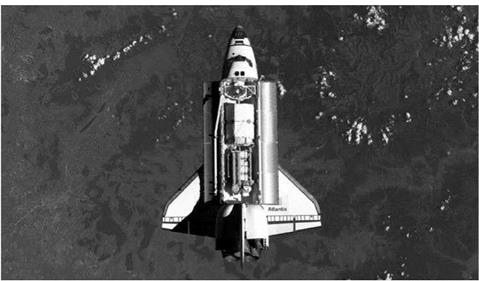

Rendezvous with ISS took place on September 11, Flight Day 3. Houston joked, “Atlantis is headed your way with a brand new piece of the Space Station in its trunk.’’ As the Shuttle approached the station, Jett and Ferguson performed the r-bar pitch manoeuvre, to allow the station crew to take high-resolution photographs of the Shuttle’s underside. In Houston, Pam Melroy was Capcom and remarked, “Station, we see you have visitors. Tell them to give us a wave.’’

Atlantis docked to PMA-2 at 06: 48. Even as the pressure and leak checks between the two vehicles were taking place, Ferguson and Burbank activated the RMS and used it to lift the 17.5-tonne P-3/P-4 ITS out of Atlantis’ payload bay and manoeuvred it to the position where it could be handed over to the SSRMS, leaving it in that location. The hatches between the two vehicles were opened at 08 : 30, and the Shuttle crew transferred to ISS. The visitors were greeted enthusiastically by the three-man Expedition-13 crew before receiving the standard safety briefing. MacLean then joined Williams at the SSRMS station in Destiny and used it to complete the hand-over of the P-3/P-4 ITS from the Shuttle’s RMS, at 10: 52. The new ITS element was left hanging on the SSRMS overnight to become thermally stabilized in the space environment. The day continued with the EMU’s and EVA tools being transferred to Quest. It ended with Tanner and Stefanyshyn – Piper locking themselves in Quest for the program’s first use of the new “camp-out” procedures. The two EVA astronauts slept in Quest, with the pressure reduced, in order to reduce the pre-breathing time required to remove the nitrogen from their bloodstream before an EVA.

|

Figure 73. STS-115 crew (L to R): Heidemarie M. Stefanyshyn-Piper, Brent W. Jett, Jr., Joseph R. Tanner, Daniel C. Burbank, Christopher J. Ferguson, Steven G. MacLean. |

|

Figure 74. STS-115 approaches the ISS carrying the P-3/P-4 Integrated Truss Structure. |

Construction of ISS resumed on September 12, 2006. At 05:17, Tanner and Stefanyshyn-Piper transferred their EMUs to internal battery power, thereby officially starting their first EVA. After collecting their tools the two astronauts made their way to the P-3/P-4, which had previously been moved to its deployed position at the exposed end of the P-1 ITS and held in place by the SSRMS, while motorised bolts were driven home. The pair quickly got ahead of their timeline as they worked their way through a series of tasks including connecting power cables on the ITS, releasing launch restraints on the Solar Array Blanket Box and the Beta Gimbal Assembly. They also configured the Solar Alpha Rotary Joint (SARJ), which would allow the deployed photovoltaic arrays to track the Sun. Having completed their schedule they began a series of “get-ahead” tasks in preparation for the flight’s second EVA. They removed the covers that would allow them to access and remove the launch lock bars from the SARJ. As Tanner removed one of the covers a bolt and washer detached from the SARJ and drifted away. The pair returned to the Quest airlock at 11: 43, ending the EVA after 6 hours 26 minutes. During the morning, MCC-Houston had informed Jett that additional inspections of Atlantis’ heatshield were not required. Meanwhile, the two crews spent the remainder of the day transferring equipment and supplies between the two spacecraft. The day ended with Burbank and MacLean “camping out’’ in Quest.

Burbank and MacLean commenced their EVA at 05: 05 September 13. The entire EVA was devoted to activating the SARJ, with Stefanyshyn-Piper operating the SSRMS in order to use its cameras to video the activities. Both EVA astronauts released the launch locks, but had to overcome several small difficulties, including a stuck bolt and a faulty EMU helmet camera. Next, they prepared the new P-3/P-4 ITS for the MBS, which would be used to transport the SSRMS along the completed ITS. With the major tasks completed, they turned their attention to additional “get – ahead” tasks, including the removal of a keel pin and drag link. They also removed a Space Vision System target, used to align the RMS and SSRMS in order to remove the P-3/P-4 ITS from Atlantis’ payload bay. Finally, they installed a temporary rail stop for the CETA.

With Burbank and MacLean back inside at 12: 16, after an EVA lasting 7 hours 11 minutes, MCC-Houston began a 4-hour activation and checkout of the SARJ, designed to ensure all systems were working. They engaged Drive Lock Assembly 1 (DLA-1) and rotated the car-sized joint through 180°. When they engaged DLA-2 later in the day they received no talk-back indication to indicate that it had engaged properly. A back-up procedure also failed to result in the required indication of successful engagement. Deploying the P-4 SAWs was delayed while the problem was investigated overnight, and was overcome by a software work-around sent up from the ground in the early hours of the next morning.

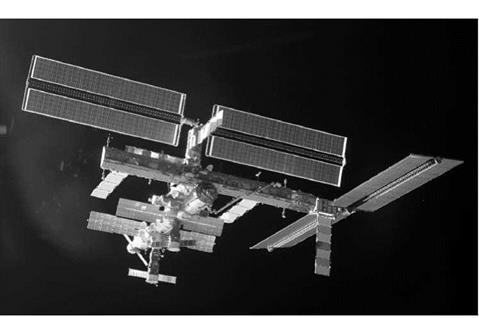

At 04: 00, September 14, MCC-Houston commanded the SAWs on the P-4 ITS to deploy, a procedure that was not completed until 08: 44. For the STS-115 crew the day was a rest-day, while the Expedition-13 crew continued transferring equipment and stores between the two spacecraft. The 66 kilowatts of electrical power produced by the new SAWs was directed to the P-3/P-4 ITS’ own systems. It would not be distributed to the remainder of ISS until the system was rewired and the cooling system activated during the flight of STS-116, then planned for December 2006. During the day the SSRMS underwent a “walk-off”, from the MBS to the exterior of Destiny.

During preparations for the third EVA a remote power controller tripped out resulting in the loss of power to Quest’s depressurisation pump. Tanner and Stephanyshyn-Piper left the airlock and moved to the adjacent Unity module, while still pre-breathing oxygen through face masks. The problem was found to be a momentary power spike and, following checks to ensure there was no short circuit, the breaker was reset, the pump reactivated, and the two astronauts returned to the airlock to continue preparations for their EVA, which was delayed by 45 minutes.

Tanner and Stefanyshyn-Piper began their EVA at 06: 00, September 15. Once outside they separated in order to complete individual tasks. Tanner installed bolt retainers on the P-6 Beta Gimbal Assembly, which assisted in the pitch orientation of the SAWs. He also attempted to re-engage a four-bar hinge, which had failed to engage during the flight of STS-97. Meanwhile, Stefanyshyn-Piper recovered the MISSE-5 materials science experiment. Working together, the two astronauts next prepared the Space Radiator on the P-3/P-4 ITS for deployment by removing hardware installed to protect the radiator during launch. With that task completed, they deployed an S-band antenna support assembly on the S-1 ITS. They also deployed a shroud on the failed S-band antenna support assembly, which would be returned to Earth on a later Shuttle flight. Separating again, Stefanyshyn-Piper replaced a base-band signal processor and transponder on S-1, while Tanner installed a heatshield on an antenna group interface tube to help prevent overheating in the area when ISS was placed in particular attitudes in relation to the Sun. Their final tasks included installing an external wireless TV antenna and performing infrared video of Atlantis’ wing leading edges. The EVA ended at 12: 42, after 6 hours 42 minutes. After their EVA, the two astronauts joked together, “Kind of nice up there on top,’’ Tanner remarked. “Yes, but I didn’t get to look around much. At least, I can say I’ve been there,’’ replied Stefanyshyn-Piper. Tanner added, “Not too many people have.’’

September 16 was a light day for the STS-115 crew; they had the morning off after their hectic work schedule so far. After lunch they joined the Expedition-13 crew for a joint crew photograph, a press conference, and personal interviews. Jett told the media, “We are off to a good start… We have a lot of complex missions ahead. We had a few small problems, but the team did a wonderful job of resolving them. I think it bodes well for the future.’’ The two crews also performed the final transfer of equipment between the two spacecraft, as well as moving some of the items of debris, produced during the last EVA, to Progress M-57.

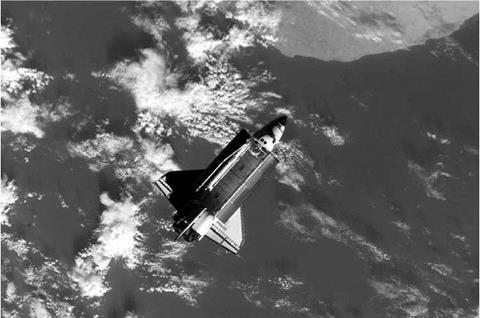

The two crews said their farewells on September 17. The hatches between the two vehicles were closed at 06 : 27 and, following pressure checks, Atlantis undocked at 08: 50. Twenty minutes later Ferguson began the first full fly-around of ISS since 2002. During the fly-around the crew were able to view and photograph the results of their hard work over the past few days. Atlantis manoeuvred away from ISS at 10: 30. In Russia, final preparations were underway for the launch of Soyuz TMA-9, with the Expedition-14 crew.

|

Figure 75. STS-115: Atlantis departs the station with an empty payload bay. |

|

Figure 76. STS-115: construction has resumed. The station displays the new P-3/P-4 Solar Array Wings and ammonia radiator at right. Meanwhile, the Solar Array Wings and ammonia radiator are still deployed on the P-6 Integrated Truss Structure, mounted on the Z-1 Truss. |

During the morning of September 18 the Expedition-13 crew, Vinogradov, Williams, and Reiter, were faced with a malfunctioning Elektron oxygen generator in Zvezda, which had been powered off for the visit of STS-115. At a request from Korolev, Vinogradov attempted to restart the Elektron, but it soon shut down again on its own. Following several other attempts the unit was finally restarted. Vinogradov was working on it when it overheated, causing smoking from a melted rubber seal, a strong odour, and the possible release of a small amount of the chemical irritant, potassium hydroxide. The crew were instructed to manually activate a fire alarm to allow the station’s software to shut down the air circulation fans. They were also told to don surgical masks, goggles, and gloves. Vinogradov cleared up and bagged a clear liquid that had leaked from the unit. The Elektron was ultimately restarted and the air circulation fans powered on within the hour. On the same day the crew of STS-115 made a final inspection of Atlantis’ heatshield, nosecap, and wing leading edges. In the words of Shuttle Programme Manager Wayne Hale, “You can call it anxiety, or you can call it smart. But it’s what we do these days. We have no reason not to go look and put every concern to rest.’’

At 03: 00, September 19, Houston linked the crews of ISS, STS-115, and Soyuz TMA-9, which had been launched the previous day, to allow them to talk to each other. Williams told the Soyuz crew, “It’s a little crowded in the sky today… We look forward to having you guys onboard.’’ Jett told the Expedition-13 crew, “We’ll see you back on Earth sometime soon.’’ Following the conference Atlantis’ crew tested the orbiter’s flight control surfaces and RCS thrusters. They spent the day packing up for re-entry, but during the day the flight was extended by one day, to allow for further inspections of the Shuttle’s exterior after video cameras showed debris drifting away from the vehicle. The decision to extend was also based on deteriorating weather forecasts for the landing site. TMA-9 continued its approach to rendezvous, while the Expedition-13 crew watched the undocking of Progress M – 57 at 20: 30. The spacecraft re-entered the atmosphere and burned up just after midnight.

Having left the RMS/OBSS positioned above the payload bay overnight, so that controllers could use its video cameras to inspect the area, it was used to inspect Atlantis’ underside on September 20. A shim and a tile spacer seen in an earlier inspection were found to be gone. When no issues with the Shuttle’s heat shielding were revealed, flight managers cleared Atlantis for landing in the early hours of the following morning. Meanwhile, Soyuz TMA-9 had docked to Zvezda. The crew entered the station later that morning. Atlantis’ crew went to bed at 21:45, waking again at 21:45 to face the final hours of their flight. Atlantis landed at KSC, Florida at 06: 21,21 September, after a flight lasting 11 days 19 hours 6 minutes.

On September 22, Michael Griffin told a press conference, “It’s obvious to me we are re-building the kind of momentum that we have had in the past and that we need if we are to finish the Space Station… We have an awesome task in front of us. I think we will make it.’’

|

SOYUZ TMA-9 DELIVERS THE EXPEDITION-14 CREW

|

When the Soyuz TMA-9 crew were originally named, the spaceflight participant involved was Japanese entrepreneur Daisuke Enomoto, but he was grounded for undisclosed medical reasons that caused him to fail his final medical examination. Enomoto was replaced by his back-up Anousheh Ansari, the Iranian-born daughter of an adventure capitalist, supporter of the X-Prize (won by Rutan’s SpaceShipOne) and business partner to the Federal Space Agency of Russia in attempts to develop commercial access to space. Following her late allocation to the flight Ansari would perform many of Enomoto’s experiments, rather than those with which she had already begun practising, for her own flight.

Ansari flew without an Iranian flag on the sleeve of her Sokol pressure suit, and had promised her American and Russian programme managers that she would make no political speeches while in orbit. Before her launch she had remarked:

“I believe when you see the Earth without boundaries, without borders, without race, that you can see how important it is for us, everyone, to be more understanding of our neighbours, our friends, other people’s beliefs, religions, race and not make issues to start wars… One thing that I’m hoping is that I’d like for people all over the world to see a different face of an Iranian-born individual, something different than what they see on TV and in the media… Also, I think my flight has become sort of a ray of hope for young Iranians living in Iran, helping them to look forward to something positive, because everything that they’ve been hearing is all so very depressing and talks of war and talks of bloodshed.’’

Soyuz TMA-9 was launched from Baikonur at 00:09, September 18, 2006. Following a standard rendezvous it docked to Zvezda’s wake at 01: 21, September 20. The hatches were opened at 03:34, allowing Lopez-Alegria, Tyurin, and Ansari to enter ISS. The Expedition-13 crew greeted their reliefs before giving them the standard safety briefing. The intense hand-overs of previous Expedition crews were lightened somewhat by the fact that Reiter had been on the station as part of the Expedition-13 crew since July 2006 and would remain as the third member of the Expedition-14 crew until December 2006.

Lopez-Alegria described his flight:

“The goals, first of all, are to continue the assembly of the Space Station, which has sort of been on hold for a while since the Columbia accident, so in general our mission is going to be to receive a couple of Shuttle flights, do some construction while they’re there. After they’ve gone, we’re going to be receiving three Progress vehicles, which means a lot of cargo, loading, unloading. In general, the focus is going to be construction and assembly… [E]very time something comes, you’ve got to unpack it, and that takes time. And time is going to be a significant challenge for us. The second thing is, when we unpack that stuff there’s got to be some place to put it, and the station is already pretty full of stowage. The challenge is going to be to find where to stow the stuff that’s brought up.’’

During the hand-over period, Ansari performed two ESA experiments, while the two Expedition crews worked together to ensure a smooth transition. Reiter transferred his couch liner and Sokol pressure suit from Soyuz TMA-8 to Soyuz TMA-9, while Ansari took hers in the opposite direction. Throughout the period the Elektron oxygen generator remained powered off and the astronauts burned four SFOG candles each day to produce the required amount of oxygen. Despite now having 120 new SFOGs onboard the crew continued to burn the 40 out-of-date candles in order to use them up. By the end of the hand-over period only four old SFOGs remained. Vinogradov and Tyurin replaced the liquids unit in Elektron and powered it on. It failed shortly thereafter and was designated to be “hard-failed’’ by Korolev. New spare parts would be delivered by Progress M-58, in October 2006. Throughout the period both Expedition crews participated in ongoing experiments in both sectors of the station. Vinogradov has described the hand-over period saying:

“[T]here also is a bit of a symbolic significance, when the commanders shake hands and say, here, you accept the station and I hand the station over to you and have a successful flight and all. This is quite an important moment associated with a lot of responsibility, and it’s quite busy. Then the previous crew leaves and you stay there alone; it’s kind of sad, actually. And in a way it’s a little bit worrisome. You’re there, and you don’t have anyone to ask or clarify things. When you part, it’s quite an emotional moment. I don’t think that there is a single crew that leaves with joy saying, oh fine, it’s finally over and I’m going to be home. It’s always a sensation that you’re leaving your home because always it’s that time that evokes a certain amount of sadness. Of course you understand the landing, your family, your kin and friends and all the joys of living on Earth, but it does make you want to go back and it’s quite a sad time when you have to leave the station.’’

Williams explained:

“The plan in the future is to rotate two out of three crewmembers on Soyuz every six months, as we have been doing for the last few years. The third crewmember will rotate on Shuttle; and by default that means that there’s a phased rotation. So Thomas gets there after we’ve been there a little while, and when we get ready to depart, with the next Soyuz, and its crew arrival in the fall, when we depart Thomas will stay on board. He’ll be the experience and help with the hand-over of the beginning of… Expedition 14.’’

|

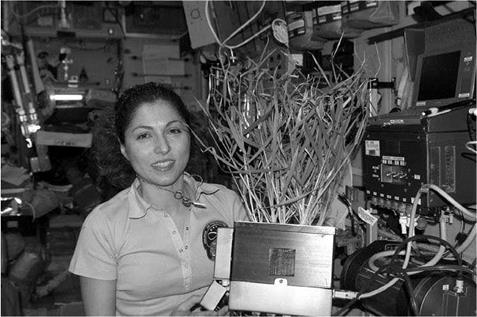

Figure 77. Expedition-14: American/Iranian spaceflight participant Anousheh Ansari flew to the ISS on Soyuz TMA-9 with the Expedition-14 crew. She returned to Earth with the Expedition-14 crew. |

On September 24, Vinogradov and Williams completed systems checks in Soyuz TMA-8 before a full dress rehearsal of the undocking and re-entry procedures, with Ansari the following day. The official hand-over took place on September 27. After a week-long hand-over, followed by fond farewells, Vinogradov, Williams, and Ansari shut themselves in Soyuz TMA-8. Undocking occurred at 17: 53, September 28. After a routine re-entry, Soyuz TMA-8 landed at 21: 13, the same day. Vinogradov and Williams had been aloft for 182 days 22 hours 43 minutes. Ansari’s flight had lasted 10 days 21 hours 5 minutes. Following standard recovery procedures the crew was flown to Kustani for the official welcome home ceremony and then to Zvezdny Gorodok for their 45-day rehabilitation and debriefing. Vinogradov had reviewed his definition of success before launch:

“First of all I would say it’s this internal feeling that you’ve done everything that you could. The satisfaction with the flight actually comes later, after some evaluations are performed and it’s all kind of reviewed and summed up. But the most important thing I would say is the appreciation of your work, of the crew, is when the next crew comes in and can tell you, guys, thanks for doing this and that, it’s because of you that we were able to, sort of standing on your shoulders, continue this work. I would say that this is probably the most important assessment of your work on the station that those who are coming after you would be using your experience, would stand on the basis of the results of your work.’’

By those standards Expedition-13 had been a great success.

On September 26, NASA Administrator Michael Griffin visited Chinese space facilities. He told a press conference:

“This is an exploratory visit. This is a first date—if you will. I think we need to let it evolve. There are differences between our nations on key points. One of the major points is the control of missile technology. We have been very firm on that in the past, and I believe we will continue to be firm on the importance of appropriately controlling missile technology. China has clearly made great strides in a relatively short period of time… I have been very impressed with the capabilities, experience and intellectual quality of the people we have met. The facilities we have seen have been first rate.”

Griffin made it clear that there were no plans to invite China to join the International Space Station partnership in the near future.

Meanwhile, Russia had increased the cost of their spaceflight participant flights to ISS on a Soyuz taxi flight from $20 million to $21 million. Elsewhere, Space Adventures, the company that markets spaceflight participant flights on behalf of the Russian Federal Space Agency, had also begun talking about an option for their customers to perform a 90-minute EVA whilst docked to ISS. Training for and performing an EVA would cost the customer an additional $15 million on top of the new $21 million fee. Meanwhile, Russian space officials told the media that their country could expect to fall behind “irreparably” if they failed to develop the six – person Kliper spacecraft. Russia and Europe were also considering the development of a new heavy-lift launch vehicle, the Oural programme, as a possible replacement for the Soyuz-2 and Ariane-V launch vehicles at some point in the 2020s.