PREPARING FOR THE INTERNATIONAL PARTNER MODULES

With Discovery gone and the P-6 ITS relocated, Whitson, Malenchenko, and Tani settled down to the remainder of their occupation. They continued their daily routine of experiments, maintenance, and exercise, but beyond that they would oversee the

|

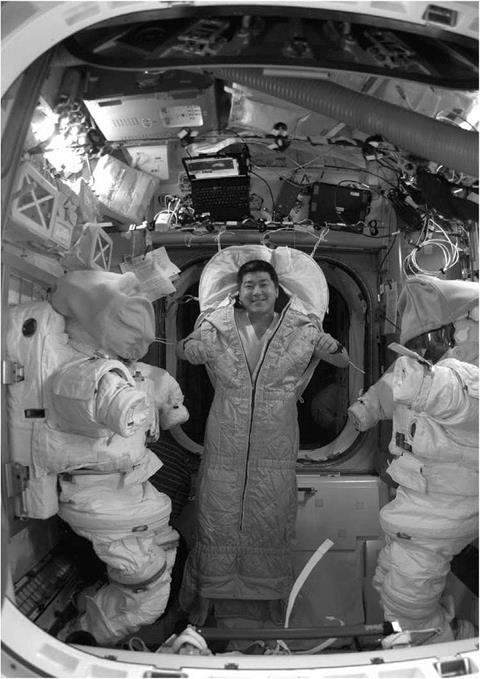

Figure 108. Expedition-16: Daniel Tani poses in his sleeping bag mounted between two EMUs inside the Quest airlock. |

transformation of ISS into a truly International Space Station. The Expedition-16 crew had a quiet day on November 5, in the wake of Discovery’s departure and in advance of a busy period during which Harmony would be moved to Destiny’s ram. That work began on November 8, when the crew spent the day preparing their EMUs and the Quest airlock for a Stage EVA.

At 04: 54, November 9, Whitson and Malenchenko exited Quest to carry out work that should have been completed by the STS-120 crew, but had been rescheduled because of the urgent need to repair the P-6 ITS SAW. Making their way to Destiny’s ram, their first task was to disconnect the SSPTS cables from PMA-2, before disconnecting eight other cables between Destiny and the PMA. Whitson also removed a CETA light on Destiny, to clear the area for equipment trays to be installed at a later date. Their third task was to disconnect the rigid umbilicals on the side of Destiny. Both astronauts covered the receptacles left open by the de-mated umbilicals with dust caps as they worked. Separating, Whitson completed connections for the PDGF that would be used when Harmony was relocated. Malenchenko moved up to the Z-1 Truss’ wake face to remove and replace a failed RPCM. Working together once more, they made their way back to Harmony, on Unity’s port CBM. On the new module’s exposed end, they removed a dust cover that had protected the CBM in that area. As they removed the dust cover, Tani observed from inside the station. Looking through the window here, all I can see is a big aluminium foil. It looks like turkey cooking in the oven.’’ Whitson and Malenchenko recovered the dust cover for disposal on a Progress spacecraft. Malenchenko’s next task was to re-route an electrical cable at the wake of the Z-1 Truss, while Whitson moved to the “rats’ nest’’, the area between the Z-1 Truss and the S-0 ITS, where she made changes to the electrical connections in that region. Next, Whitson recovered a base-band signal processor and returned to the airlock with it. It would be returned to Earth and refurbished. Finally, Malenchenko redistributed EVA tools between two storage bags and then moved one of those bags to the S-0 ITS. The EVA ended when they returned to Quest, at 10: 49, after 6 hours 55 minutes exposed to vacuum. Even as Whitson and Malenchenko completed their EVA, STS-121 Atlantis was moving out to the launchpad where the European Columbus Science Laboratory was already waiting in its payload container.

In orbit, Whitson and her crew began preparations on November 13, for the arrival of Columbus. On that date, Tani commanded the SSRMS from inside Destiny and used it to grapple the PDGF on PMA-2. At 04: 35 Whitson commanded the first of four mechanical bolts holding the PMA in place to unwind. The final bolt was released at 05 : 02, and Tani moved the PMA away from Destiny’s ram 10 minutes later. The SSRMS was used to manoeuvre the PMA to a position below Destiny where the station’s cameras were used to inspect its mating surfaces. When the survey was complete, Tani moved the PMA to its new position on Harmony’s outboard CBM, at which time Whitson commanded the four bolts to secure it in place. The final bolt was secured at 06: 29. Later that same day, Houston placed a ban on EVAs. A ground test of an EMU on Earth had resulted in a smell of smoke. Subsequent testing of the suit revealed no signs of burning.

The following day, Tani and Whitson repeated their roles, using the SSRMS to grapple Harmony and release the CBM bolts holding it in place. Whitson released the first bolt at 03:58 and the last at 04:21.Tani then used the SSRMS to move Harmony from its temporary position on the side of Unity and relocated it on Destiny’s ram. The relocation manoeuvre was completed at 05: 45, much earlier than planned. Capcom Kevin Ford told them, “You guys are really cooking with gas.’’ During the manoeuvre the station had passed over the Atlantic Ocean; Whitson looked out of Destiny’s window and remarked, “It’s amazing. I love my job!’’

On November 15, the P-1 radiator was deployed, increasing the area available to the station’s ammonia cooling system. On the same day, NASA cleared the EMUs on the station for future EVA work. NASA’s Lynett Madison stated, “There is no indication of combustion or an electrical event. We’ve been cleared to conduct spacewalks.” The smoke odour detected in the suit test earlier in the week was thought to have been caused by a canister of metal oxide used during ground tests of the suit.

Whitson described the two EVAs that she and Tani had originally been expecting to make to outfit Harmony, in the following terms:

“The EVAs that have to be conducted between the arrival of Node-2 [Harmony] and before arrival of Columbus are critical. We can’t accept the new module without the completion of those EVAs… [T]he two EVAs that Dan and I will conduct actually will lay what we call the umbilical trays, and they are the fluid lines that will connect the Thermal Control System that’s based in the truss. We have to run them along the laboratory module and then connect [them] to the Node-2. [T]he reason that’s important is the Node-2 has six different heat exchangers; some of those will be providing the thermal heat rejection for each of the new modules that come up later. So it’s got a big thermal job, and we have to connect all those lines that will allow it to happen. Obviously we also have to do the electrical and the data connections as well, so that we’ll be able to transmit data and receive telemetry back and forth throughout not only the Node-2 module but then later, through the laboratory modules on Columbus and the JEM … We do some mating on the inside: the internal Thermal Control System’s mated on the inside. We also have power and data connections that are done on the inside.’’

The first of those two EVAs began at 05: 10, November 20, 2007, when Whitson and Tani left the Quest airlock wearing American EMUs. Exiting the airlock as the station passed over the Atlantic Ocean, Tani remarked, “A nice day at the office here.’’

After preparing their tools, they set about individual tasks to maximise their time outside. Whitson removed an ammonia jumper, part of a temporary cooling system, on the outside of the station, vented it, and then stowed it securely in place. The jumper’s removal allowed for the establishment of the new Loop-A, one of two loops in the permanent cooling system. As she worked Whitson reported that frozen ammonia crystals were escaping from the open end of the system, “They appear

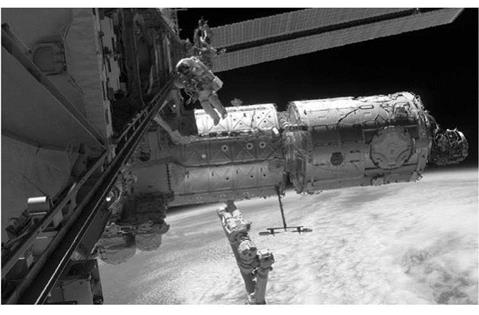

|

Figure 109. Expedition-16: Peggy Whitson makes a Stage EVA following the departure of STS – 120. In the background Harmony has been relocated to Destiny’s ram, and PMA-2 is on Harmony’s ram. |

frozen and just bouncing off me.’’ Houston replied, “Not a problem at this time. We’re ready to press on.’’

At the same time, Tani retrieved a bag of tools left outside the station during the EVA on November 9. He then removed two fluid caps, as part of the preparation of the permanent cooling loop. His next task was to reconfigure an electrical circuit that was used to fire a pyrotechnic during the deployment of the P-1 cooling radiator on November 15. Both astronauts then made their way to the centre of the S-0 ITS where they co-operated to unbolt the 6.5 m long Loop-A fluid tray from its storage position. In order to move the tray, they took it in turns to move ahead of the tray and secure lines to ensure that it did not drift away if they lost control of it. The tray was then moved forward and the next set of lines attached to it before the previous set of lines were released. In that manner they moved the tray to the exterior of Harmony, where they secured it in place. Next, they secured six fluid connections, two at the tray, two on the S-0 ITS, and two inbetween those two locations. Tani’s final planned task was on the port side of Harmony, where he mated 11 avionics lines, meanwhile Whitson configured heating cables and connected electrical harnesses linking PMA-2 and Harmony. With time to spare they were also able to complete a number of “get-ahead” tasks. Tani connected five avionics lines on Harmony’s starboard side, before joining Whitson to connect a series of redundant umbilicals and connect the SSPTS cables to PMA-2 in its new location. The EVA ended at 12: 26, after 7 hours 16 minutes.

Whitson and Tani’s next EVA took place on November 24 and was for all intents and purposes a mirror image of the EVA completed four days earlier. Where the earlier EVA had set up Harmony’s primary cooling loop (Loop-A), the second EVA would establish the back-up cooling loop (Loop-В). Ammonia, circulated through the umbilicals installed during these two EVAs, would take up the heat produced by Harmony’s electrical equipment and transport it to the large radiators on the ITS, where the heat would be radiated to space and the ammonia recirculated. The EVA began at 04:50, with the crew exiting from Quest wearing American EMUs. They worked together to prepare their tools, before Whitson removed, vented, and stowed the ammonia lines associated with the original, temporary cooling loop. Tani disconnected two fluid caps in preparation for the establishment of Loop-В of the permanent cooling loop. His next task was to relocate an articulated portable foot restraint from its location on the port side of Harmony, to its new position on the lower portion of the module’s ram endcone. The two astronauts then joined together to move the Loop-В cooling tray from the S-0 ITS to its permanent location on the port avionics tray on Destiny’s zenith, where they bolted it in place. They used the same method to move the fluid tray as they had during the previous EVA. With the Loop-В fluid tray in place, they made the same six connections that they had made on the Loop-A fluid lines: two on the fluid tray, two on the S-0 ITS, and two inbetween. Whitson then made her way to Harmony’s starboard side where she removed the launch restraints from the petals on the CBM that would provide soft-docking for Columbus when STS-122 delivered it. That delivery was planned for December 2007. At the same time, Tani made his way to the starboard SARJ, removed one of the thermal covers, allowing him to photograph the joint and recover samples of the metal shavings contaminating the joint. It was a repeat of the work he had carried out during the visit of STS-120. During the inspection, Tani reported, “I see the same damage that I saw before… I would say there is more damage than I saw before.’’ Tani took the thermal cover back to Quest, leaving the joint open to the video cameras on the SSRMS. The video survey would be completed after the visit of STS-122 and would include at least one full rotation of the SARJ. The EVA ended at 11: 54, after 7 hours 4 minutes. The crew had light-duty days on November 25 and 26 following their week of hard work.

On November 28, NASA announced that they feared Harmony may have developed a pressure leak, although the overall pressure leakage rate for the whole station had not increased. (All pressurised modules leak. The rate of leakage is included in the module’s design stage and confirmed during manufacture and prelaunch testing. Under normal operations the gases used to pressurise the module are supplied at a rate that will maintain the correct internal pressure in addition to the known leakage rate.) That evening, Whitson was instructed to secure the area between Harmony and Unity’s hatches, so that the internal pressure could be monitored. The fact that the overall pressure leak rate had not increased suggested that the problem might actually lie in one of the measuring instruments and might not be a leak at all. The test was repeated and again showed no loss of pressure in the space between the two hatches. As a result, preparations went ahead on the station for the arrival of STS-121, in early December, while Houston continued to monitor the “pressure leak” problem.

With Harmony now on Destiny’s ram and PMA-2 on Harmony’s ram, ISS was finally configured to receive the next few Shuttle flights, which would deliver the European and Japanese modules to the station. The astronauts from those two nations would begin flying to the station in greater numbers and with increasing regularity. Following the delivery of Node-3, with its extra sleeping facilities, the station’s crew would be increased to six people, increasing its capacity to perform first-class orbital science. The last two items of American ISS hardware, the S-6 ITS and the Cupola, would also be launched and installed. In time the European ATV and the Japanese HTV would begin delivering consumables to the station alongside the Russian Progress spacecraft.

As the STS-122 launch was delayed in November 2007, the future schedule for ISS through the end of the Shuttle programme was mapped out:

|

STS-122 |

DISCOVERY: Columbus |

|

STS-123 |

ENDEAVOUR: JEM ELM-PS (placed in temporary position) and Canadian Dextere robotics system. Four EVAs to install equipment |

|

Soyuz TMA-12 |

Expedition-17 crew up. |

|

STS-124 |

ATLANTIS: Kibo, two EVAs to install lab and Japanese RMS. Relocate JEM ELM PS to permanent position |

|

STS-128 |

ENDEAVOUR: MPLM. Establish six-person Expedition crew |

|

H-IIA |

ATV-1 |

|

STS-119 |

ENDEAVOUR: S-6 Truss |

|

Soyuz TMA-13 |

Expedition-18 crew up. |

|

STS-126 |

MPLM |

|

STS-127 |

DISCOVERY: JEM-ES and JEM-EF |

|

STS-129 |

DISCOVERY: EXPRESS Logistics Carrier 1 & 2 |

|

STS-130 |

MPLM |

|

STS-131 |

DISCOVERY: EXPRESS Carrier 3 & 4 |

|

STS-123 |

ENDEAVOUR: Node-3 and Cupola |

|

STS-132 |

ENDEAVOUR: EXPRESS Logistics Carrier 5 & 6 |

As the Shuttle approaches the end of its career, the Russian Soyuz will become the principal vehicle for crew delivery and recovery including the astronauts from all of the ISS International Partners. Given the support of Congress and the new President (the Presidential election is in 2008) the American Project Constellation spacecraft, Orion, and its Ares-1 launch vehicle will be developed and flight-tested. As 2007 drew to a close, only Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton had made positive statements on Orion during her campaign. Clinton’s spokesperson, Isaac Baker, had stated, “Senator Clinton does not support delaying the Constellation Programme and intends to maintain American leadership in space exploration.’’ Meanwhile, Senator Barack Obama had called for Project Constellation to be delayed for 5 years and the money spent on education and social programmes.

If they are built, Orion and Ares-1 will assume the role of American crew delivery and recovery in the ISS programme, but flying to ISS is not the principal role for which Orion is being built.

As America prepares to return to the Moon, hopefully taking their International Partners with them, what role does that leave for ISS? During the pre-launch interview for his Expedition-11 flight, Sergei Krikalev voiced his view of the importance of the ISS programme to Project Constellation and the future of human spaceflight in general:

“[The International Space] Station is not the ultimate goal. It’s an intermediate goal. That may be the significance of this Station. This is an intermediate step you have to make before you go any further. Life science experiments can be conducted on the Station to understand how far we can go with the configuration we have right now and what else we need to do to provide more efficiency of human beings on this long-duration mission, and long-distance mission. We continue to conduct technological experiments to see how materials change and how they behave inside, and outside, the Station, to know how to build new vehicles. We are even learning how micro-organisms change inside the Station, and some of these organisms might be a biological hazard for materials inside. Certain microorganisms can destroy insulation on wires and create big trouble. We have to be prepared especially if we are to go on long-distance missions. On these longdistance missions (not only long-duration missions, as we are flying on the Station right now) you have to be much more autonomous. Even small things that people don’t think about very often can change the quality of our development. Being [a] participant on Mir flights and now [on an] ISS flight I see that [the] experience of people, on the ground, operational experience, is very important. Unless we gain this experience, unless we do this step, we will never be able to move any farther from the Earth. It needs to be done on the Station before we can make any further steps.’’