FIRST TO FLY

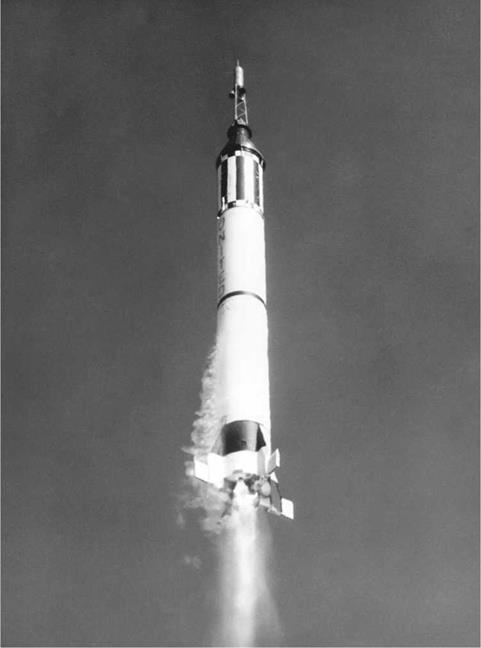

“There was a lot less vibration and noise rumble than I had expected,” Shepard later explained. “It was extremely smooth – a subtle, gentle, gradual rise off the ground. There was nothing rough or abrupt about it. But there was no question that I was going, either. I could see it on the instruments, hear it on the headphones, feel it all around me.” [5]

Mildly surprised by the lack of vibration, Shepard was also pleased to find that he did not have to turn his radio receiver up to full volume in order to hear incoming transmissions. After communications were verified, he transmitted every 30 seconds in order to maintain voice contact and report the state of the spacecraft systems to the ground.

According to Flight Director Chris Kraft, “A communication procedure had been developed between the astronaut and the control center so that if the cabin and suit pressures were not maintained, an abort was to be initiated.” This would restrict the peak altitude to 70,000 feet. “By aborting at this time (i. e., between T+l min. 16 secs. and T+1 min. 29 secs.), the time above 50,000 feet could be limited to about 60 to 70 seconds.” [6] But things proceeded smoothly.

Shepard later told Life magazine, “For the first minute, the ride continued smooth and my main job was to keep the people on the ground as relaxed and informed as I could. I reported that everything was functioning perfectly, that all the systems were working, that the g’s were mounting slightly [just] as predicted. The long hours of rehearsal had helped. It was almost as if I had been there before. It was enormously strange and exciting, but my earlier practice gave the whole thing a comfortable air of familiarity. [And] Deke’s clear transmissions in my headphones reassured me still more.” [7]

The first critical moment was 1 minute 24 seconds after liftoff, when the vehicle passed through the point of maximum dynamic pressure, known in NASA parlance as Max Q, when the aerodynamic stress reached its peak. Shepard’s head began to shake in an involuntary reaction to the vibration and his vision blurred a little.

“I was at two and a half times my normal weight. So far the flight was a piece of cake,” Shepard later stated. “I was through the smoothest part of powered ascent, and now came the rutted road, the barrier I had to cross before leaving the atmosphere behind. [The] Redstone was hammering at shock waves gathering stubbornly before its passage, slicing from below the speed of sound through the barrier to supersonic [heading] straight up. Now I was in Max Q, the zone of maximum dynamic pressure where the forces of flight and ascent challenged the booster rocket. My helmet slammed against the contour couch. Eighteen inches before me the instrument panel

|

became a blur, almost impossible to read. One thousand pounds of pressure for every square foot of Freedom 7 was trying to crack the capsule. I started to call Deke, but changed my mind. A garbled transmission at this point could send Mercury Control into a flap. It might even trigger an abort. And then the Redstone slipped through the hammering blows into smoothness. Out of Max Q, I keyed the mike.

“‘Okay, it’s a lot smoother now. A lot smoother.’

“‘Roger,’ said Deke.” [8]

The shutdown of the booster came at T+2 minutes 22 seconds at an acceleration of 6.2 g’s, which meant in effect that Shepard now weighed 1,000 pounds. He was finding it difficult to talk as the g-forces constricted his throat and vocal cords. At the same time, a signal was transmitted to the spacecraft for its escape tower to separate. Above Shepard, a large solid-fuel rocket roared into life and fierce flames erupted from its three canted nozzles, ripping the tower loose from the spacecraft and pulling it away at a safe angle. “Immediately I noticed the noise in tower jettisoning. I didn’t notice any smoke coming by the porthole as I’d expected I might in my peripheral vision. I think maybe I was riveted on the ‘tower jettison’ green light which looked so good in the capsule.” [9] He promptly threw the ‘retro-jettison’ switch to its ‘disarm’ setting.

|

Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson watches the progress of the flight, together with President John F. Kennedy and First Lady, Jackie Kennedy. (Photo: NASA) |

Ten seconds after the tower departed, the spacecraft separated from the Redstone by severing the connecting Marman clamp and firing the three posigrade rockets on the retropack for a duration of one second.

After the flight, Shepard said he was aware of the noise of the separation rockets firing. “I don’t recall thinking anything in particular at separation, but there’s good medical evidence that I was concerned about it at the time. My pulse rate reached its peak here [at] 132, and started down afterward.” [10]

If the automatic systems had failed, the escape tower and spacecraft separation events could have been manually initiated.

“Cap sep is green,” Shepard reported, as he slipped into a weightless state. As he later observed, “Moments before, I had weighed 1,000 pounds. Now a feather on the surface of the Earth weighed more than I did. Being weightless was… wonderful, marvelous, incredible. [It was a] miracle in comfort. The tiny capsule seemed to expand magically as pressure points vanished. No up, no down, no lying or sitting or standing. A missing washer and bits of dust drifted before my eyes. I laughed out loud. I’d expected silence at this point, with the atmosphere something far below me and no rush of wind despite so many thousands of miles an hour. No friction. No turbulence. But instead there was the murmur of Freedom 7, as though a brook were running mechanically through its structure. Inverters moaned, gyroscopes whirred, cooling fans had their own sound, cameras hummed, the radios crackled and emitted their tones before and after conversational exchanges. The sounds flowed together, some dull, others sharper. [It was a] miniature mechanical orchestra. I found those unexpected sounds most welcome; they meant things were working, doing, pushing, and repeating. They were the sounds of life.” [11]

Five seconds after Freedom 7 separated from the booster the periscope extended, and the autopilot initiated a turnaround maneuver in which the spacecraft was yawed through 180 degrees to position the heat shield forward, in the direction of reentry. In effect, Shepard was flying backwards.

One major objective of the mission – which would greatly distinguish it from the automated flight of Yuri Gagarin – was timed to start at T+3 minutes 10 seconds, when Shepard switched off the automatic control systems and took manual control of the spacecraft’s attitude or angular position.

“I made this manipulation one axis at a time, switching to pitch, yaw, and roll in that order until I had full control of the craft. I used the instruments first and then the periscope as reference controls. The reaction of the spacecraft was very much like that obtained in the air-bearing [ALFA] trainer…. The spacecraft movement was smooth and could be controlled precisely.” [12]

He was to maintain manual control of the spacecraft throughout the remainder of the flight by using various combinations of the attitude and rate-control systems, also known as the fly-by-wire mode.

At T+3 minutes 50 seconds, he made a number of visual observations using the periscope. These included such things as weather fronts, cloud coverage, and certain preselected reference points on the ground. As he said later, “I was zinging along high above the planet’s atmosphere at better than five thousand miles per hour, but there was nothing by which to judge speed. You need relative comparison for that: a tree, a building, a passing spacecraft. My view of the outside universe was restricted to the

|

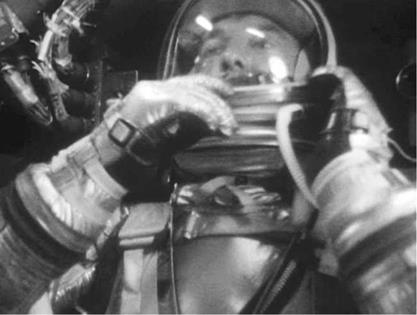

Shepard’s helmeted face was filmed during the flight to record his eyes roving over the instrument panel in order to assess whether better placement of some instruments might be beneficial for future astronauts. (Photo: NASA) |

capsule’s two small portholes, and through those I saw that very deep blue, almost jet black, sky. There was only one available reference to tell me I was actually moving: the Earth below.” [13]

He quickly realized there was a problem with the periscope. While sitting on the launch pad enduring the numerous delays he had tried to look downward through the periscope and found that he was almost blinded by sunshine filling the cabin. He had immediately inserted filters to cut down the glare, but had forgotten to remove the filters prior to launch. Now, peering through the scope, he could only see the view below in shades of gray. As he reached for the filter knob the pressure gauge on his left wrist accidentally bumped against the abort handle.

“I stopped that movement real quick,” he explained later. “Sure, the escape tower was gone, and hitting the abort handle might not have caused any great bother, but this was still a test flight, and I wasn’t about to play guessing games.”

Gray or not, he found the view quite enthralling.

“On the periscope,” he informed Mission Control. “What a beautiful view!” [14]